Blockbuster History: The size of a bug

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: Marvel's Ant-Man shows us the fun side of being so small that you have to look up to an ant. Ah, but what of the scary side?

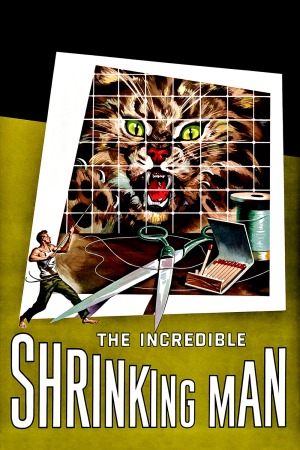

To begin with, it's thoroughly unreasonable to expect a '50s sci-fi thriller to star Orson Welles. But the teaser trailer for 1957's The Incredible Shrinking Man makes me faintly angry for promising such a miracle, knowing full well that it would never come to pass.

But enough about film advertising. In truth, even deprived of Welles, The Incredible Shrinking Man is a pretty terrific example of its genre, despite some rather obvious and avoidable flaws of story structure and a rather massive shortchanging of the sociological analysis of Richard Matheson's source novel, in favor of more straightforward survivalist adventure. In the hands of Jack Arnold, Universal's best genre film director at that time (he was responsible for Creature from the Black Lagoon, the studio's best monster movie since the 1930s, and he went uncredited for reshooting the best parts of This Island Earth), the film has a merciless pace and excellent scenes of tension, carried on the back of some of the very best special and visual effects of the decade. And beyond the film's admirable strengths as a taut spectacle, Matheson's screenplay ends on an especially strong note, surprisingly managing to achieve in one speech all the moral philosophising that the film needs to feel like it has real depth and nuance, and that despite tapping from the same brand of flowery religiosity that did in many a sci-fi film of the time.

Having gone ahead and given itself that title, the film wastes the minimal possible amount of time in getting going. The Careys, Scott (Grant Williams) and Louise (Randy Stuart) are enjoying a boat ride on the Pacific coast, and at the exact moment that Louise heads belowdecks, a mysterious fog rolls in, covering Scott with a reflective sheen that apparently soaks into his bare skin. Six months later, he discovers that all of his clothes are slightly too large: loose in the belly, too high at the neck, too long in the arms. A doctor's appointment confirms that he's inexplicably become 5'11" instead of his customary 6'1", and he's dropped from 190 to 180 lbs. The doctor (William Schallert) comes up with pleasant, rational explanations for why this is absolutely nothing to worry about, but evidence increasingly pile up that not only is Scott smaller than he used to be, he's continuing to shrink. We're still in the first reel.

God bless the film for its haste in getting us to this point, but it's symptomatic of the film's one overriding, unanswerable shortcoming. It's worth pointing out that the novel is non-linear: it intercuts the story of the very tiny Scott trapped in his own basement, facing down a spider, with the story of how he came to be in that predicament. In other words, it throws the good stuff at the reader first, and then luxuriates in the fine details of the story in the sure knowledge that our attention has been grabbed. By straightening out the narrative line, the movie suddenly makes itself vulnerable to the killer of all B-movies - and classic status notwithstanding, this is nothing if it's not a B-movie - which is that it permits the viewer to become bored. In order to make sure that this doesn't happen, Arnold absolutely flies through all of the material between Scott's discovery of his loose clothes and the moment that his pet cat finally decides that this tiny little biped would probably be an extremely fun thing to chase and dismember, thus precipitating his fall into the depths of the basement. That escalation starts some 33 minutes into the movie, which means that an entire feature's worth of psychological discombobulation, domestic strife, and medical suspense are condensed into just a half of an hour.

Pragmatically, it works: every last moment of the film from the shot of the cat looming through the window of the dollhouse Scott now calls home to the stately appearance of the words "THE END" is gripping, and the film gets to it fast enough that there's no chance of having burned off the goodwill the audience inherently brings to a movie titled The Incredible Shrinking Man (by which I mean, if you're going to hate a movie for showing a man the size of a bug being menaced by a spider, you know damn well enough not to start watching it). Subjectively, I'd say that the film almost doesn't survive it. The paradox is that, by racing through the material so quickly, Arnold and Matheson don't give it any chance to land and linger, which makes it difficult to feel very connected to the onscreen action. Which, in turn, means that it's more boring, because of the exact technique the film uses to keep us from being bored. The most significant example of what I'm talking about is a subplot about Scott's friendship with a little person from a carnival, Clarice (April Kent), who is at that point just about his size; it's undernourished, and the ramifications are left totally ignored (I mean, hell, you could get a whole act just out of what this means to his increasingly frustrated marriage), and while it adds some depth to Scott's arc, it's patently obvious how much more it could be providing to the film with a little TLC.

Please, though, let me be absolutely clear: at its very worst, The Incredible Shrinking Man merely repeats the sins of any given '50s sci-fi movie, and it repeats them at a higher level or sophistication. At its very worst. At its best, you can count on one hand the number of its direct peers that match or top it. Even before Scott ends up in the basement there are several individually terrific sequences that stress the helplessness and weariness of the Careys' situation, or the awkwardness and dysfunction of Scott's condition. In the latter case, there's a scene with Scott's brother (Paul Langton) talking to Louise in front of a chair, and it's only belatedly and thanks to a blunt cut that we realise Scott has been sitting in that chair the whole time. In the former, the best of the film's many exemplary forced-perspective shots (it's every inch as good as the famously ambitious forced perspective in The Fellowship of the Ring, 44 years later), Louise and Scott are having a difficult time talking, and she refuses to make eye contact, thus not only further selling the illusion but also turning a visual effect setpiece into one of the best character moments in the movie.

It's in the basement, though, where the film shines, in every way. The effects work is peerless, with close-up photography of a tarantula seamlessly married to footage of Williams, and the sets and props are impressively convincing simulations of the quotidian world at several times the magnification, an exciting change from the usual chintzy foam objects populating the era's sci-fi. And Arnold stages the action from acute angles that emphasise the size and peril of these routine objects: a scene where Scott tries to use a paint-stirring stick to cross a deadly crevasse of a foot deep or more is my personal favorite part of the movie, finding a way to make the laughably common (dude can't even throw away his spent paint supplies) into something alien and nightmarish. The translation of the banal domestic world of cats, junk in the basement, and crappy water heaters into an endless chain of danger is the purest kind of horror, and it's what gives The Incredible Shrinking Man so much of its brutal punch. It's a more immediate, visceral surrogate for the thoughtful introspection of the book, which crops up only in the last scene and, to lesser effect, in the film's annoying reliance on voice-over; but it's a worthy trade-off, since it means this is also one of the most immediate, visceral sci-fi thrillers of its generation, on top of being one of the most technically audacious.

To begin with, it's thoroughly unreasonable to expect a '50s sci-fi thriller to star Orson Welles. But the teaser trailer for 1957's The Incredible Shrinking Man makes me faintly angry for promising such a miracle, knowing full well that it would never come to pass.

But enough about film advertising. In truth, even deprived of Welles, The Incredible Shrinking Man is a pretty terrific example of its genre, despite some rather obvious and avoidable flaws of story structure and a rather massive shortchanging of the sociological analysis of Richard Matheson's source novel, in favor of more straightforward survivalist adventure. In the hands of Jack Arnold, Universal's best genre film director at that time (he was responsible for Creature from the Black Lagoon, the studio's best monster movie since the 1930s, and he went uncredited for reshooting the best parts of This Island Earth), the film has a merciless pace and excellent scenes of tension, carried on the back of some of the very best special and visual effects of the decade. And beyond the film's admirable strengths as a taut spectacle, Matheson's screenplay ends on an especially strong note, surprisingly managing to achieve in one speech all the moral philosophising that the film needs to feel like it has real depth and nuance, and that despite tapping from the same brand of flowery religiosity that did in many a sci-fi film of the time.

Having gone ahead and given itself that title, the film wastes the minimal possible amount of time in getting going. The Careys, Scott (Grant Williams) and Louise (Randy Stuart) are enjoying a boat ride on the Pacific coast, and at the exact moment that Louise heads belowdecks, a mysterious fog rolls in, covering Scott with a reflective sheen that apparently soaks into his bare skin. Six months later, he discovers that all of his clothes are slightly too large: loose in the belly, too high at the neck, too long in the arms. A doctor's appointment confirms that he's inexplicably become 5'11" instead of his customary 6'1", and he's dropped from 190 to 180 lbs. The doctor (William Schallert) comes up with pleasant, rational explanations for why this is absolutely nothing to worry about, but evidence increasingly pile up that not only is Scott smaller than he used to be, he's continuing to shrink. We're still in the first reel.

God bless the film for its haste in getting us to this point, but it's symptomatic of the film's one overriding, unanswerable shortcoming. It's worth pointing out that the novel is non-linear: it intercuts the story of the very tiny Scott trapped in his own basement, facing down a spider, with the story of how he came to be in that predicament. In other words, it throws the good stuff at the reader first, and then luxuriates in the fine details of the story in the sure knowledge that our attention has been grabbed. By straightening out the narrative line, the movie suddenly makes itself vulnerable to the killer of all B-movies - and classic status notwithstanding, this is nothing if it's not a B-movie - which is that it permits the viewer to become bored. In order to make sure that this doesn't happen, Arnold absolutely flies through all of the material between Scott's discovery of his loose clothes and the moment that his pet cat finally decides that this tiny little biped would probably be an extremely fun thing to chase and dismember, thus precipitating his fall into the depths of the basement. That escalation starts some 33 minutes into the movie, which means that an entire feature's worth of psychological discombobulation, domestic strife, and medical suspense are condensed into just a half of an hour.

Pragmatically, it works: every last moment of the film from the shot of the cat looming through the window of the dollhouse Scott now calls home to the stately appearance of the words "THE END" is gripping, and the film gets to it fast enough that there's no chance of having burned off the goodwill the audience inherently brings to a movie titled The Incredible Shrinking Man (by which I mean, if you're going to hate a movie for showing a man the size of a bug being menaced by a spider, you know damn well enough not to start watching it). Subjectively, I'd say that the film almost doesn't survive it. The paradox is that, by racing through the material so quickly, Arnold and Matheson don't give it any chance to land and linger, which makes it difficult to feel very connected to the onscreen action. Which, in turn, means that it's more boring, because of the exact technique the film uses to keep us from being bored. The most significant example of what I'm talking about is a subplot about Scott's friendship with a little person from a carnival, Clarice (April Kent), who is at that point just about his size; it's undernourished, and the ramifications are left totally ignored (I mean, hell, you could get a whole act just out of what this means to his increasingly frustrated marriage), and while it adds some depth to Scott's arc, it's patently obvious how much more it could be providing to the film with a little TLC.

Please, though, let me be absolutely clear: at its very worst, The Incredible Shrinking Man merely repeats the sins of any given '50s sci-fi movie, and it repeats them at a higher level or sophistication. At its very worst. At its best, you can count on one hand the number of its direct peers that match or top it. Even before Scott ends up in the basement there are several individually terrific sequences that stress the helplessness and weariness of the Careys' situation, or the awkwardness and dysfunction of Scott's condition. In the latter case, there's a scene with Scott's brother (Paul Langton) talking to Louise in front of a chair, and it's only belatedly and thanks to a blunt cut that we realise Scott has been sitting in that chair the whole time. In the former, the best of the film's many exemplary forced-perspective shots (it's every inch as good as the famously ambitious forced perspective in The Fellowship of the Ring, 44 years later), Louise and Scott are having a difficult time talking, and she refuses to make eye contact, thus not only further selling the illusion but also turning a visual effect setpiece into one of the best character moments in the movie.

It's in the basement, though, where the film shines, in every way. The effects work is peerless, with close-up photography of a tarantula seamlessly married to footage of Williams, and the sets and props are impressively convincing simulations of the quotidian world at several times the magnification, an exciting change from the usual chintzy foam objects populating the era's sci-fi. And Arnold stages the action from acute angles that emphasise the size and peril of these routine objects: a scene where Scott tries to use a paint-stirring stick to cross a deadly crevasse of a foot deep or more is my personal favorite part of the movie, finding a way to make the laughably common (dude can't even throw away his spent paint supplies) into something alien and nightmarish. The translation of the banal domestic world of cats, junk in the basement, and crappy water heaters into an endless chain of danger is the purest kind of horror, and it's what gives The Incredible Shrinking Man so much of its brutal punch. It's a more immediate, visceral surrogate for the thoughtful introspection of the book, which crops up only in the last scene and, to lesser effect, in the film's annoying reliance on voice-over; but it's a worthy trade-off, since it means this is also one of the most immediate, visceral sci-fi thrillers of its generation, on top of being one of the most technically audacious.

Categories: adventure, blockbuster history, horror, science fiction, thrillers, universal horror