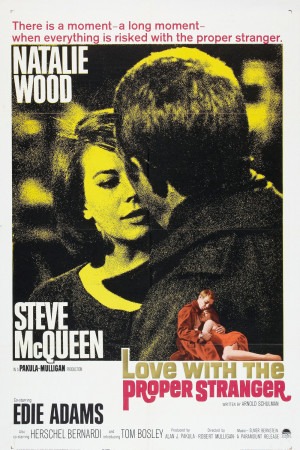

Strangers and other lovers

A review requested by Nathaniel R, with thanks for contributing to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser. And happy birthday, Nathaniel!

The primary characteristic of Love with the Proper Stranger, in defiance of its handsomely poetic title, is that it is fucking blunt. That is the first thing it wants us to be aware of. The movie launches right into itself without any warm-up, opening with a loud scrape as a metal grate is rolled back from a door. Then come the credits, warmly scored with Elmer Bernstein's romantic title theme, and all seems well until the credits peter out and we're pitched into the teeming mass of bodies in a local musicians union in New York, with people desperately looking for work and people absently looking for musicians. Whatever gracefulness might have tried to sneak in is forcefully and crudely stamped out, and we don't even know who our characters are yet.

And that bluntness continues to apply once the plot shows up. The script, by Arnold Schulman, starts off well after the beginning of the story: a young woman, Angie Rossini (Natalie Wood), fights her way into the crowd to catch the attention of the distinctly older Rocky Papasano (Steve McQueen). They verbally fence for a couple of moments as he fails to place her and pretends that he's doing it to be cute, and she eventually runs out of patience and just comes out with it: he got her pregnant a couple of months back, and she wants to know if he's going to help her take care of the situation. And it is at this moment that the film won me over to its side as much as it ever could: not just for the forcefulness of having two characters in a movie from 1963 talk about an unwanted pregnancy in language that's barely coded at all (and in fact, all of the coding that's done is around the hoped-for abortion, not the pregnancy itself), but for the narrative audacity of starting off at this point. We don't know anything about these people, only that a few months ago, he connived her into having sex and now she's more flatly disappointed than pissed, while he's infinitely more embarrassed than contrite.

It's easy to imagine a dozen different movies incorporating this plot point after an extended introductory prologue, or as the midpoint to a lengthier, more holistic romantic drama. Love with the Proper Stranger skips all of that in favor of presenting the characters at their roughest and rawest; it's a suitably aggressive start to a movie that exemplifies the lacerating realism that cinema had just barely invented and still had no idea what to do with. Five years later, you'd swear it was part of the coalescing New Hollywood Cinema; instead, it's one of those marvelous one-off experiments in frayed anti-style and boundary-shattering adult content that fluttered around the late '50s and most of the '60s, ultimately clearing the path for the New Hollywood to come in. Which is kind of the entire idea behind the dual career of director Robert Mulligant and producer Alan J. Pakula, a team responsible for much of the "Edgy, Smart, and Grown-Up" dramatic cinema of the period.

If you're looking for it going into the film, you can kind of see the tatters of a more classical mode of filmmaking sticking to its ribs: the characterisation of most of the side characters, the third act, the presence of a radio-friendly title track. But for the most part, this is slice-of-life realism at its most severe. It tells barely any story - Angie and Rocky batter around New York trying to scrounge up enough money for her surgery in the first half of the movie, taking up about one day. Then they have a falling out, and he realises he's in love with her and tries to make up for his crass, rude behavior. The writing is full of half-delivered sentences that the actors swallow up in nervous tics and inarticulate thoughtfulness, offering a precise snapshot of urban working class society in a certain time and place.

Even the fact that it's headlined by two enormously charismatic movie stars doesn't really hurt its sense of realism, though neither Wood nor McQueen is terribly convincing as a New York Italian. But the sheer shock of seeing these two gorgeous people in this guttural setting has the effect of making that setting "pop". And even more than that, the graceless, acerbic performance Wood gives, fearlessly violating her ingénue persona, seems all that much harsher if we know Wood's earlier work (McQueen, bless him, simply isn't all the way there: he gives it his absolute best as an actor, and it's certainly not bad, but it's impossible to square the cultural memory of the coolest movie star in American history with the figure he's inhabiting here; he has great chemistry with Wood, but it's not exactly the same thing as great acting). It's a calculated move for the actress, beyond a doubt, with her career over the first half of the '60s operating on virtually a film-by-film basis to slowly stretch her and grow her up in front of the audience. Two years earlier, Wood was playing a young, virginal member of a different New York ethnic group to dubious effect in West Side Story; in '62, she played the world's most famous stripper as a guileless girl in Gypsy. A sexually experienced Good Girl is a natural next step in that evolution, and there's a degree to which it feels a bit of a mechanical effort for Wood to put on and take off the trappings of young adult sophistication. But it's still probably the most difficult role she'd taken to that point in her career, and she's always one of the film's strongest elements. The sense she never quite shakes of a little girl play-acting at being a tough adult describes Angie as well as it does the actor playing her, and it's hard to say where it falls between canny casting, smart directing of a limited performer, and just plain great acting on the part of someone who clearly did a lot of thinking about how her character walks, talks, wears clothes, and observes others.

The two main characters and the city holding them and the social issue they provide a window into are, in basically that order, Mulligan and Schulman's primary interests; Love with the Proper Stranger is best at sitting down and watching Angie and Rocky slowly and painfully learn about each other, and it's very nearly as good at taking a snapshot of what New York's poorer enclaves looked like in the early '60s. It stumbles a bit when it tries to inhabit those enclaves: with nearly every meaningful character in the film an Italian Catholic, the film is at its most goofily old-fashioned when it tries to show off that world, with some largely absurd results. "If you tell your papa, I break your face", says Rocky's mother (August Ciolli) as she lovingly presses money into his hands, and this is one of the broadest lines in the movie (coming at the end of what is certainly its broadest scene), but there's a lot of film that's more or less adjacent to that register of stereotype, even if the two central lovers are themselves always treated respectfully and honestly. I should qualify that - they're treated that way up until the last act, where the film becomes a bright, bubbly comedy very suddenly, and frankly, not very well. The tonal mismatch with the low simmering harshness of the first and change is stunning and disruptive, although the film successfully rights itself for a very sweet last scene that marries the froth and the grit in an effective mixture.

All these flaws are what they are; the fact is that far more of the film is outstanding rather than otherwise. At its best, when it's squatting down to watch the characters muddle around, the film's sense of real life that just happens to have a camera in front of it is peerless. I am particularly fond of a scene in which Angie's family forces an awkward suitor played by Tom Bosley to join them at the table; it's a masterwork of organically overstuffed production design and faultless naturalistic dialogue, and it has some of the best non-Wood acting in the movie. In moments like this, when everything clicks into a rich, messy depiction of New Yorkers spilling into each others' lives, the film reaches absolute perfection and impresses me more than anything else in the Pakula-Mulligan canon: even more than the legendary To Kill a Mockingbird, for it contains none of that film's self conscious Importance-with-a-capital-I. Of course, not all of Love with the Proper Stranger is at that level, and it has the misfortune to frontload most of its finest moments. But taken as a whole it's absolutely terrific, and thoroughly undeserving of its weird invisibility and unavailability relative to many weaker films in both Wood's and McQueen's iconic careers.

The primary characteristic of Love with the Proper Stranger, in defiance of its handsomely poetic title, is that it is fucking blunt. That is the first thing it wants us to be aware of. The movie launches right into itself without any warm-up, opening with a loud scrape as a metal grate is rolled back from a door. Then come the credits, warmly scored with Elmer Bernstein's romantic title theme, and all seems well until the credits peter out and we're pitched into the teeming mass of bodies in a local musicians union in New York, with people desperately looking for work and people absently looking for musicians. Whatever gracefulness might have tried to sneak in is forcefully and crudely stamped out, and we don't even know who our characters are yet.

And that bluntness continues to apply once the plot shows up. The script, by Arnold Schulman, starts off well after the beginning of the story: a young woman, Angie Rossini (Natalie Wood), fights her way into the crowd to catch the attention of the distinctly older Rocky Papasano (Steve McQueen). They verbally fence for a couple of moments as he fails to place her and pretends that he's doing it to be cute, and she eventually runs out of patience and just comes out with it: he got her pregnant a couple of months back, and she wants to know if he's going to help her take care of the situation. And it is at this moment that the film won me over to its side as much as it ever could: not just for the forcefulness of having two characters in a movie from 1963 talk about an unwanted pregnancy in language that's barely coded at all (and in fact, all of the coding that's done is around the hoped-for abortion, not the pregnancy itself), but for the narrative audacity of starting off at this point. We don't know anything about these people, only that a few months ago, he connived her into having sex and now she's more flatly disappointed than pissed, while he's infinitely more embarrassed than contrite.

It's easy to imagine a dozen different movies incorporating this plot point after an extended introductory prologue, or as the midpoint to a lengthier, more holistic romantic drama. Love with the Proper Stranger skips all of that in favor of presenting the characters at their roughest and rawest; it's a suitably aggressive start to a movie that exemplifies the lacerating realism that cinema had just barely invented and still had no idea what to do with. Five years later, you'd swear it was part of the coalescing New Hollywood Cinema; instead, it's one of those marvelous one-off experiments in frayed anti-style and boundary-shattering adult content that fluttered around the late '50s and most of the '60s, ultimately clearing the path for the New Hollywood to come in. Which is kind of the entire idea behind the dual career of director Robert Mulligant and producer Alan J. Pakula, a team responsible for much of the "Edgy, Smart, and Grown-Up" dramatic cinema of the period.

If you're looking for it going into the film, you can kind of see the tatters of a more classical mode of filmmaking sticking to its ribs: the characterisation of most of the side characters, the third act, the presence of a radio-friendly title track. But for the most part, this is slice-of-life realism at its most severe. It tells barely any story - Angie and Rocky batter around New York trying to scrounge up enough money for her surgery in the first half of the movie, taking up about one day. Then they have a falling out, and he realises he's in love with her and tries to make up for his crass, rude behavior. The writing is full of half-delivered sentences that the actors swallow up in nervous tics and inarticulate thoughtfulness, offering a precise snapshot of urban working class society in a certain time and place.

Even the fact that it's headlined by two enormously charismatic movie stars doesn't really hurt its sense of realism, though neither Wood nor McQueen is terribly convincing as a New York Italian. But the sheer shock of seeing these two gorgeous people in this guttural setting has the effect of making that setting "pop". And even more than that, the graceless, acerbic performance Wood gives, fearlessly violating her ingénue persona, seems all that much harsher if we know Wood's earlier work (McQueen, bless him, simply isn't all the way there: he gives it his absolute best as an actor, and it's certainly not bad, but it's impossible to square the cultural memory of the coolest movie star in American history with the figure he's inhabiting here; he has great chemistry with Wood, but it's not exactly the same thing as great acting). It's a calculated move for the actress, beyond a doubt, with her career over the first half of the '60s operating on virtually a film-by-film basis to slowly stretch her and grow her up in front of the audience. Two years earlier, Wood was playing a young, virginal member of a different New York ethnic group to dubious effect in West Side Story; in '62, she played the world's most famous stripper as a guileless girl in Gypsy. A sexually experienced Good Girl is a natural next step in that evolution, and there's a degree to which it feels a bit of a mechanical effort for Wood to put on and take off the trappings of young adult sophistication. But it's still probably the most difficult role she'd taken to that point in her career, and she's always one of the film's strongest elements. The sense she never quite shakes of a little girl play-acting at being a tough adult describes Angie as well as it does the actor playing her, and it's hard to say where it falls between canny casting, smart directing of a limited performer, and just plain great acting on the part of someone who clearly did a lot of thinking about how her character walks, talks, wears clothes, and observes others.

The two main characters and the city holding them and the social issue they provide a window into are, in basically that order, Mulligan and Schulman's primary interests; Love with the Proper Stranger is best at sitting down and watching Angie and Rocky slowly and painfully learn about each other, and it's very nearly as good at taking a snapshot of what New York's poorer enclaves looked like in the early '60s. It stumbles a bit when it tries to inhabit those enclaves: with nearly every meaningful character in the film an Italian Catholic, the film is at its most goofily old-fashioned when it tries to show off that world, with some largely absurd results. "If you tell your papa, I break your face", says Rocky's mother (August Ciolli) as she lovingly presses money into his hands, and this is one of the broadest lines in the movie (coming at the end of what is certainly its broadest scene), but there's a lot of film that's more or less adjacent to that register of stereotype, even if the two central lovers are themselves always treated respectfully and honestly. I should qualify that - they're treated that way up until the last act, where the film becomes a bright, bubbly comedy very suddenly, and frankly, not very well. The tonal mismatch with the low simmering harshness of the first and change is stunning and disruptive, although the film successfully rights itself for a very sweet last scene that marries the froth and the grit in an effective mixture.

All these flaws are what they are; the fact is that far more of the film is outstanding rather than otherwise. At its best, when it's squatting down to watch the characters muddle around, the film's sense of real life that just happens to have a camera in front of it is peerless. I am particularly fond of a scene in which Angie's family forces an awkward suitor played by Tom Bosley to join them at the table; it's a masterwork of organically overstuffed production design and faultless naturalistic dialogue, and it has some of the best non-Wood acting in the movie. In moments like this, when everything clicks into a rich, messy depiction of New Yorkers spilling into each others' lives, the film reaches absolute perfection and impresses me more than anything else in the Pakula-Mulligan canon: even more than the legendary To Kill a Mockingbird, for it contains none of that film's self conscious Importance-with-a-capital-I. Of course, not all of Love with the Proper Stranger is at that level, and it has the misfortune to frontload most of its finest moments. But taken as a whole it's absolutely terrific, and thoroughly undeserving of its weird invisibility and unavailability relative to many weaker films in both Wood's and McQueen's iconic careers.

Categories: comedies, domestic dramas, love stories