Unspeakable filth

A review requested by David Greenwood, with thanks for contributing to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

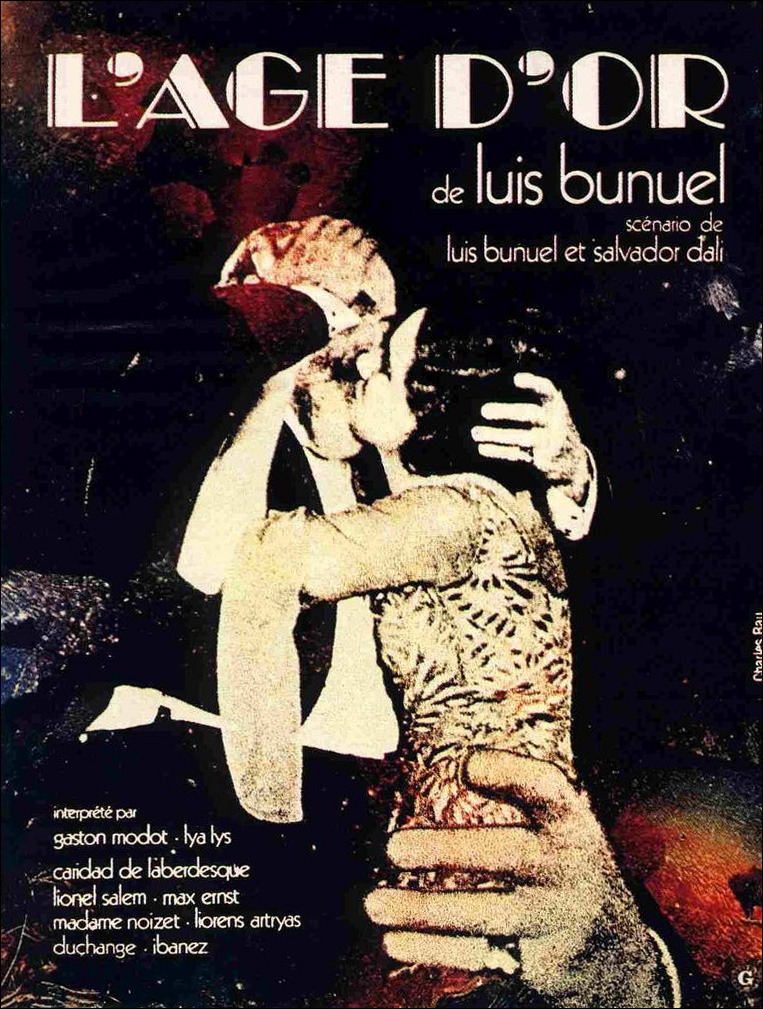

L'âge d'or, an hour-long 1930 feature, is the second of the two collaborations between France-based Spanish surrealists Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, and it is certainly less jam-packed with iconic "every film buff alive knows this shot" shots than their 1929 short Un chien andalou. But it also better - oh, fuck me. "Better" is a word that has no place in this conversation at all. Buñuel and Dalí were, quite specifically, not looking to do things that would get them praise for being "good". Using "better" is exactly missing the point. L'âge d'or is, let us say, the more complex of the two, and the more thematically probing, which is probably inevitable given that it's four times as long. It is absolutely the more naked political film - Dalí was an iconoclast who just wanted to up-end people's expectations, Buñuel a committed radical who wanted to tear down the Catholic Church and and the right-wing European governments of that period with all the force and rage he could muster. In its combination of rabid left-wing politics and vigorous surrealism, L'âge d'or is the first truly "Buñuelian" film, then, and it is not surprising to learn that the relationship between the two artists had deteriorated to the point that Dalí had virtually nothing to do with the film's production once the screenplay was completed - according to a deliciously tawdry but hard-to-verify legend, Buñuel chased Dalí off the set on the first day with a hammer.

The film has a scenario that starts to reveal itself more and more explicitly as it moves along, but for a healthy span of the beginning, it doesn't seem that way. Instead, L'âge d'or picks up right where Un chien andalou left off, as a series of seemingly disconnected visual gags, though "gag" is in the eye of the beholder. Violent shocks of aggressive absurdity is probably closer to the mark. The first of these is a series of images of scorpions, taken from a nature documentary, stitched together with large blocks of intertitles - the movie is a sound/silent hybrid, but more on that later - which pretty neatly sets up the mood of the film as a series of lashing, defensive attacks by venomous arthropods. Which is about as nice a sentiment as anything Buñuel and Dalí have to spare for the twin targets of their ensuing satiric broadside, the bourgeoisie and the Catholic Church.

The nature of that attack is two-fold: first in the accumulation of random startling and blasphemous imagery, second in the details of its story - perhaps surprisingly, given how cozily L'âge d'or fits into even the most proscriptive definition of Surrealism. But for as madcap and what-the-almighty-fuck-is-going-on the film's barrage of visual non sequiturs no doubt is, L'âge d'or actually tells a rather clear, straightforward story: they want to have sex (they are played by Gaston Modot and Lya Lys), and circumstances keep preventing. At first they can't because the city of Rome is founded on the exact muddy patch where they were trysting. Afterwards, they can't because of the censoriousness of Rome's most noteworthy export, Catholic morality. Finally, they can't because of psychological symbolism. Meanwhile, Jesus Christ (Lionel Salem) is raping young girls in a monastery. Only it's possible he's just a man who look as and acts uncannily like Christ. It's also probably not the case that Rome was founded in 1930. But that is when it was foundered, anyway.

So, fair is fair, it gets less clear the closer you look at it, but at the broadest possible respect, the film is first and above all about the importance of openly and honestly engaging with one's libido, and the way that all of Polite Western Upper-Middle Class society is structured to make that engagement specifically impossible. It's a randy film, with seductive blow-jobs delivered to the toes of statues, and the man feverishly imagining that advertisements are depicting abstract, disembodied vaginas, and all that good stuff; and while it presents sex as the stuff of loopy comedy, it also presents it with good-natured humor. The rest of the film, though, is pure, rage-filled mockery of the stifling rules of society, opening with a bleak joke against a quartet of bishops, ending with a nasty attack on Christ as a hero-villain out of de Sade's 120 Days of Sodom, and middling with a stuffy bourgeois party that's pelted by absurdities and anti-social provocations like something from a more sexually-charged Marx brothers movie. For anti-social behavior is presented in L'âge d'or as an aphrodisiac; both in a nod to the erotic nature of the taboo, and a clear implication that everything about this society is worth being anti.

The film is confusing and densely packed, but one thing it's surely not is subtle: there's no way to watch it without being repeatedly hit in the face by the filmmakers' disgust with the puritanical conformist urges that are linked through bizarre staging, crafty editing, and ironic sound cues with cruel exploitation of a working class that the wealthy ignore completely, with sublimated violence, with feces - much like the then eight-year-old Ulysses, another work of art to fearlessly confound social satire with pornographic depictions, L'âge d'or wants us to see and hear and think about shit, the great unifying element of all humanity and animals, that Nice People Never Talk About, and can be made to look ridiculous simply by placing them in its metaphorical proximity.

Is it all a bit puerile? Aye, undoubtedly - the 26-year-old Dalí and 30-year-old Buñuel weren't kids but they were close enough anyway to have the enraged snottiness of youth, and that's the clear animating force underneath L'âge d'or: the young person's snarl of contempt to an older generation that has massively ruined everything, "fuck you for this, and fuck you for that, and just fuck you". By drifting from boldly authoritative documentary footage and narration to cheap visual and audio gags to startling, often upsetting weirdness that seems to come from no place but a chaotic dream, the film connects the real, tangible world (the documentary) to a frolicking hell of random nonsense (the rest), and it does this with the unchecked, self-confident gusto of untried, undisciplined youth. I freely admit that it's largely for this reason that, as easily as I find myself whipped along in the film's frenzies, I can't find it in me to regard it as top-level Buñuel; most of his career later, the director would revisit much of the same ideas (the need for sexual openness, the totalitarian hypocrisy of the Catholic Church, parodic religious iconography) in Viridiana, a film as controlled and clear as L'âge d'or is freewheeling, and directly because of its greater maturity and more precise presentation, it's a far nastier and more piercing satiric assault.

But by no conceivable means does the existence of that later film mean that L'âge d'or is redundant: it has a vitality and insane level of visual creativity that are all the justification it could possibly require. As a document of capricious madness turning the world into a pile of steaming shit and then declaring things a Golden Age, the films' unpredictable shifts in tone and content, and the inexplicable content of its various jokes, could not have been bettered. It was the film that 1930 needed, and decades upon decades later, it still has potency to shock the squares like almost nothing else out of entire generations of the avant-garde.

L'âge d'or, an hour-long 1930 feature, is the second of the two collaborations between France-based Spanish surrealists Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, and it is certainly less jam-packed with iconic "every film buff alive knows this shot" shots than their 1929 short Un chien andalou. But it also better - oh, fuck me. "Better" is a word that has no place in this conversation at all. Buñuel and Dalí were, quite specifically, not looking to do things that would get them praise for being "good". Using "better" is exactly missing the point. L'âge d'or is, let us say, the more complex of the two, and the more thematically probing, which is probably inevitable given that it's four times as long. It is absolutely the more naked political film - Dalí was an iconoclast who just wanted to up-end people's expectations, Buñuel a committed radical who wanted to tear down the Catholic Church and and the right-wing European governments of that period with all the force and rage he could muster. In its combination of rabid left-wing politics and vigorous surrealism, L'âge d'or is the first truly "Buñuelian" film, then, and it is not surprising to learn that the relationship between the two artists had deteriorated to the point that Dalí had virtually nothing to do with the film's production once the screenplay was completed - according to a deliciously tawdry but hard-to-verify legend, Buñuel chased Dalí off the set on the first day with a hammer.

The film has a scenario that starts to reveal itself more and more explicitly as it moves along, but for a healthy span of the beginning, it doesn't seem that way. Instead, L'âge d'or picks up right where Un chien andalou left off, as a series of seemingly disconnected visual gags, though "gag" is in the eye of the beholder. Violent shocks of aggressive absurdity is probably closer to the mark. The first of these is a series of images of scorpions, taken from a nature documentary, stitched together with large blocks of intertitles - the movie is a sound/silent hybrid, but more on that later - which pretty neatly sets up the mood of the film as a series of lashing, defensive attacks by venomous arthropods. Which is about as nice a sentiment as anything Buñuel and Dalí have to spare for the twin targets of their ensuing satiric broadside, the bourgeoisie and the Catholic Church.

The nature of that attack is two-fold: first in the accumulation of random startling and blasphemous imagery, second in the details of its story - perhaps surprisingly, given how cozily L'âge d'or fits into even the most proscriptive definition of Surrealism. But for as madcap and what-the-almighty-fuck-is-going-on the film's barrage of visual non sequiturs no doubt is, L'âge d'or actually tells a rather clear, straightforward story: they want to have sex (they are played by Gaston Modot and Lya Lys), and circumstances keep preventing. At first they can't because the city of Rome is founded on the exact muddy patch where they were trysting. Afterwards, they can't because of the censoriousness of Rome's most noteworthy export, Catholic morality. Finally, they can't because of psychological symbolism. Meanwhile, Jesus Christ (Lionel Salem) is raping young girls in a monastery. Only it's possible he's just a man who look as and acts uncannily like Christ. It's also probably not the case that Rome was founded in 1930. But that is when it was foundered, anyway.

So, fair is fair, it gets less clear the closer you look at it, but at the broadest possible respect, the film is first and above all about the importance of openly and honestly engaging with one's libido, and the way that all of Polite Western Upper-Middle Class society is structured to make that engagement specifically impossible. It's a randy film, with seductive blow-jobs delivered to the toes of statues, and the man feverishly imagining that advertisements are depicting abstract, disembodied vaginas, and all that good stuff; and while it presents sex as the stuff of loopy comedy, it also presents it with good-natured humor. The rest of the film, though, is pure, rage-filled mockery of the stifling rules of society, opening with a bleak joke against a quartet of bishops, ending with a nasty attack on Christ as a hero-villain out of de Sade's 120 Days of Sodom, and middling with a stuffy bourgeois party that's pelted by absurdities and anti-social provocations like something from a more sexually-charged Marx brothers movie. For anti-social behavior is presented in L'âge d'or as an aphrodisiac; both in a nod to the erotic nature of the taboo, and a clear implication that everything about this society is worth being anti.

The film is confusing and densely packed, but one thing it's surely not is subtle: there's no way to watch it without being repeatedly hit in the face by the filmmakers' disgust with the puritanical conformist urges that are linked through bizarre staging, crafty editing, and ironic sound cues with cruel exploitation of a working class that the wealthy ignore completely, with sublimated violence, with feces - much like the then eight-year-old Ulysses, another work of art to fearlessly confound social satire with pornographic depictions, L'âge d'or wants us to see and hear and think about shit, the great unifying element of all humanity and animals, that Nice People Never Talk About, and can be made to look ridiculous simply by placing them in its metaphorical proximity.

Is it all a bit puerile? Aye, undoubtedly - the 26-year-old Dalí and 30-year-old Buñuel weren't kids but they were close enough anyway to have the enraged snottiness of youth, and that's the clear animating force underneath L'âge d'or: the young person's snarl of contempt to an older generation that has massively ruined everything, "fuck you for this, and fuck you for that, and just fuck you". By drifting from boldly authoritative documentary footage and narration to cheap visual and audio gags to startling, often upsetting weirdness that seems to come from no place but a chaotic dream, the film connects the real, tangible world (the documentary) to a frolicking hell of random nonsense (the rest), and it does this with the unchecked, self-confident gusto of untried, undisciplined youth. I freely admit that it's largely for this reason that, as easily as I find myself whipped along in the film's frenzies, I can't find it in me to regard it as top-level Buñuel; most of his career later, the director would revisit much of the same ideas (the need for sexual openness, the totalitarian hypocrisy of the Catholic Church, parodic religious iconography) in Viridiana, a film as controlled and clear as L'âge d'or is freewheeling, and directly because of its greater maturity and more precise presentation, it's a far nastier and more piercing satiric assault.

But by no conceivable means does the existence of that later film mean that L'âge d'or is redundant: it has a vitality and insane level of visual creativity that are all the justification it could possibly require. As a document of capricious madness turning the world into a pile of steaming shit and then declaring things a Golden Age, the films' unpredictable shifts in tone and content, and the inexplicable content of its various jokes, could not have been bettered. It was the film that 1930 needed, and decades upon decades later, it still has potency to shock the squares like almost nothing else out of entire generations of the avant-garde.