Windows to the lack of a soul

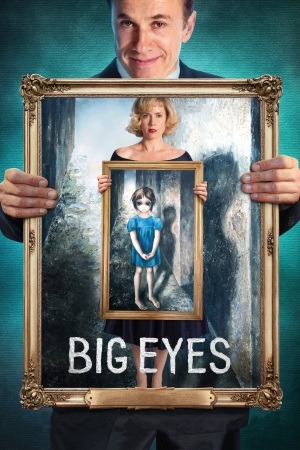

The impressive thing about Big Eyes, the most sedate film directed by Tim Burton in over a decade, maybe even two, is how many different ways its creative team came up with to interpret one script, written by Scott Alexander & Larry Karaszewski. I count at least five totally different movies jockeying for attention in this apparently simple biopic of Margaret Keane, a painter whose husband took credit for her series of sad children with enormous eyes, and made a marketing empire out of her kitschy art in the 1960s, before they divorced and she sued him to regain credit for the central focus of her adult life.

1) Amy Adams, playing Margaret, is in full on "give me a motherfucking Oscar already" mode, trembling her voice and filling her eyes with doubt and fear, emphasising the domestic tragedy of the piece and bringing a dolorous tone of suffering found nowhere else in the film.

2) As Walter Keane, the emotionally abusive, domineering husband, Christoph Waltz is channeling the bad guy in a Bob Clampett Bugs Bunny cartoon, like he made all of his acting decisions immediately upon learning that he got to be in a Tim Burton film and didn't change his mind even after finding out what an uncharacteristic Burton film this would be.

3) Cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel favors a poppy look of bright, oversaturated colors and soft focus, a cheery aesthetic that could equally serve as an ironic indictment of the era's design mentality or a sumptuous revival of it, more a remake of Burton's signature film, Edward Scissorhands, than an engagement with the actual story being told now.

4) Burton's regular composer, Danny Elfman, tosses out his usual motifs for some jazzy riffs, slinky and smoky, the adult underbelly to the 1950s and '60s that the rest of the movie cares nothing about and can't use.

5) And then Tim Burton himself, who doesn't bother to unite any of these into a unified whole, because he's far too busy trying to decide whether to take the screenplay up on its undeveloped offers to explore the question of whether or not Margaret Keane's artwork is too kitschy to be of any value, or if the fact that it has been loved and purchased by so many, including Burton himself, over the decades is proof that it matters (the latter point raised in a film-opening quote from Andy Warhol, one of the shabbier appeals to authority in recent cinema). The emphasis on the otherwise pointless characters of a snooty gallery owner played by Jason Schwartzman and an angry New York critic played by Terence Stamp (this is the first-ever team-up, and probably the last, between Burton and Stamp? That offends me on levels I didn't know I had to be offended on), and the fact that they're probably the most realised and consistent performances in the film, certainly suggests that the director had a guilty feeling that he should probably be a little more willing to regard Keane's output as tacky crap, but simply couldn't bring himself to go there. 20 years ago, in his all-time smallest film Ed Wood (also written by Alexander & Karaszewski), Burton effortlessly treated his subject's life with love and affection while also admitting, right up front, that the art Wood so passionately produced at all costs was objectively horrible. Big Eyes spends an absurd amount of its running time trying to make up its mind whether to do the same with Keane, and ends up punting.

And none of these five movies are in any way interested in the screenplay's other underdeveloped strains, investigating consumerism in America in the 1960s, the value held by art in post-WWII culture, or the sexist nature of a country that was starting to turn progressive in lumpy, inconsistent ways while all that was going on, and one woman's attempt to etch out a personality and life entirely her own a few years before society was willing to let her do that. The last of these would seem to be the only sane approach to take this material, and yet Big Eyes doesn't seem any more interested in the sociopolitical ramifications of its story than in any of the other half-dozen approaches at its fingertips: costume-driven re-enactment of Beat-era San Francisco, domestic drama, living cartoon about cartoony art, or a perfunctory, terribly-executed wacky courtroom movie, in its final act.

With nobody involved agreeing on a tone, Big Eyes offers a way in for just about everybody, but it never coheres into a thing that anybody could really regard as successful or meaningful. There's a lack of commitment to the ideas raised by the scenario and the emotional rigor brought in by Adams's performance (she's alone in trying to make this have some deep emotional meaning, or to show the human cost of Walter's cruelty and the human appeal of Margaret's paintings; it's not clear that the film benefits from this exertion in any way, but it's worth pointing out), but there's an equally frustrating refusal to just dive in and let the aesthetics, the world-building, and the sense of mania - the warped, "what kind of world goes this nuts for kitschy art?" comedy - that provide the film with whatever meager energy it's able to generate for a scene at a time.

It is, all told, profoundly undernourished and indifferently conceived: not Burton's worst film, of course (a title I imagine to be unassailable while copies of Alice in Wonderland remain undestroyed), but almost certainly his dullest and most pointless. Life flickers around in the performances - Waltz's nutso turn is vigorous, whatever else it is - and in the bright candy colors and the occasional scene where the basic, profound weirdness of Keane's paintings is allowed to hold focus beyond the muddled human drama surrounding them. Mostly, though, it's an enervating waste of talent with confused ideas and no points of interest beyond the most barbaric level of "that happened, huh".

1) Amy Adams, playing Margaret, is in full on "give me a motherfucking Oscar already" mode, trembling her voice and filling her eyes with doubt and fear, emphasising the domestic tragedy of the piece and bringing a dolorous tone of suffering found nowhere else in the film.

2) As Walter Keane, the emotionally abusive, domineering husband, Christoph Waltz is channeling the bad guy in a Bob Clampett Bugs Bunny cartoon, like he made all of his acting decisions immediately upon learning that he got to be in a Tim Burton film and didn't change his mind even after finding out what an uncharacteristic Burton film this would be.

3) Cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel favors a poppy look of bright, oversaturated colors and soft focus, a cheery aesthetic that could equally serve as an ironic indictment of the era's design mentality or a sumptuous revival of it, more a remake of Burton's signature film, Edward Scissorhands, than an engagement with the actual story being told now.

4) Burton's regular composer, Danny Elfman, tosses out his usual motifs for some jazzy riffs, slinky and smoky, the adult underbelly to the 1950s and '60s that the rest of the movie cares nothing about and can't use.

5) And then Tim Burton himself, who doesn't bother to unite any of these into a unified whole, because he's far too busy trying to decide whether to take the screenplay up on its undeveloped offers to explore the question of whether or not Margaret Keane's artwork is too kitschy to be of any value, or if the fact that it has been loved and purchased by so many, including Burton himself, over the decades is proof that it matters (the latter point raised in a film-opening quote from Andy Warhol, one of the shabbier appeals to authority in recent cinema). The emphasis on the otherwise pointless characters of a snooty gallery owner played by Jason Schwartzman and an angry New York critic played by Terence Stamp (this is the first-ever team-up, and probably the last, between Burton and Stamp? That offends me on levels I didn't know I had to be offended on), and the fact that they're probably the most realised and consistent performances in the film, certainly suggests that the director had a guilty feeling that he should probably be a little more willing to regard Keane's output as tacky crap, but simply couldn't bring himself to go there. 20 years ago, in his all-time smallest film Ed Wood (also written by Alexander & Karaszewski), Burton effortlessly treated his subject's life with love and affection while also admitting, right up front, that the art Wood so passionately produced at all costs was objectively horrible. Big Eyes spends an absurd amount of its running time trying to make up its mind whether to do the same with Keane, and ends up punting.

And none of these five movies are in any way interested in the screenplay's other underdeveloped strains, investigating consumerism in America in the 1960s, the value held by art in post-WWII culture, or the sexist nature of a country that was starting to turn progressive in lumpy, inconsistent ways while all that was going on, and one woman's attempt to etch out a personality and life entirely her own a few years before society was willing to let her do that. The last of these would seem to be the only sane approach to take this material, and yet Big Eyes doesn't seem any more interested in the sociopolitical ramifications of its story than in any of the other half-dozen approaches at its fingertips: costume-driven re-enactment of Beat-era San Francisco, domestic drama, living cartoon about cartoony art, or a perfunctory, terribly-executed wacky courtroom movie, in its final act.

With nobody involved agreeing on a tone, Big Eyes offers a way in for just about everybody, but it never coheres into a thing that anybody could really regard as successful or meaningful. There's a lack of commitment to the ideas raised by the scenario and the emotional rigor brought in by Adams's performance (she's alone in trying to make this have some deep emotional meaning, or to show the human cost of Walter's cruelty and the human appeal of Margaret's paintings; it's not clear that the film benefits from this exertion in any way, but it's worth pointing out), but there's an equally frustrating refusal to just dive in and let the aesthetics, the world-building, and the sense of mania - the warped, "what kind of world goes this nuts for kitschy art?" comedy - that provide the film with whatever meager energy it's able to generate for a scene at a time.

It is, all told, profoundly undernourished and indifferently conceived: not Burton's worst film, of course (a title I imagine to be unassailable while copies of Alice in Wonderland remain undestroyed), but almost certainly his dullest and most pointless. Life flickers around in the performances - Waltz's nutso turn is vigorous, whatever else it is - and in the bright candy colors and the occasional scene where the basic, profound weirdness of Keane's paintings is allowed to hold focus beyond the muddled human drama surrounding them. Mostly, though, it's an enervating waste of talent with confused ideas and no points of interest beyond the most barbaric level of "that happened, huh".