The cows are not what they seem

Li'l Quinquin is, I gather from those who would know, a really bad choice to have as one's first exposure to director Bruno Dumont. So before I start going on about how wonderful it is - and I am going be quite obnoxiously enthusiastic, too - you should know that I have no idea what I'm talking about.

Also, before I do that, it's worth spending a moment trying to categorise the thing that Li'l Quinquin is, as an object. It is a four-part television miniseries that aired in France in September, 2014, but that came some four months after its premiere at the 2014 Directors' Fortnight at Cannes, where it was screened as a single film clocking in at three hours and seventeen minutes. It screened in that form at the Toronto International Film Festival, and Cahiers du Cinéma named the film version as the best work of cinema of 2014, which is frankly enough for me. Particularly since it was shot in a TV-unfriendly widescreen aspect ratio that begs for a big screen and not the little online streaming bullshit that we in the United States get to enjoy, whether we're watching it in four chunks or one (it screened in New York for a week, but it's not news that New York cinephiles matter more than the rest of us). Yet even watching it in its guise as a feature film, the structure of the thing insists that we think of how it works as episodes, not a unified whole.

Regardless of what it technically is, Li'l Quinquin is an absolutely delightful experience, gathering bits and pieces of genres and styles until the act of trying to describe the feeling it imparts requires one of those 19-syllable German compound words. It's a bleak dark comedy, a police procedural, neorealist examination of the rhythm of childhood a study of morality, and a parable about racism in France; I can't do better than to call it a materialistic version of Twin Peaks that borrows its sense of humor from deadpan Scandinavian comedies and its overall tone from The 400 Blows, which means I can't do very well at all.

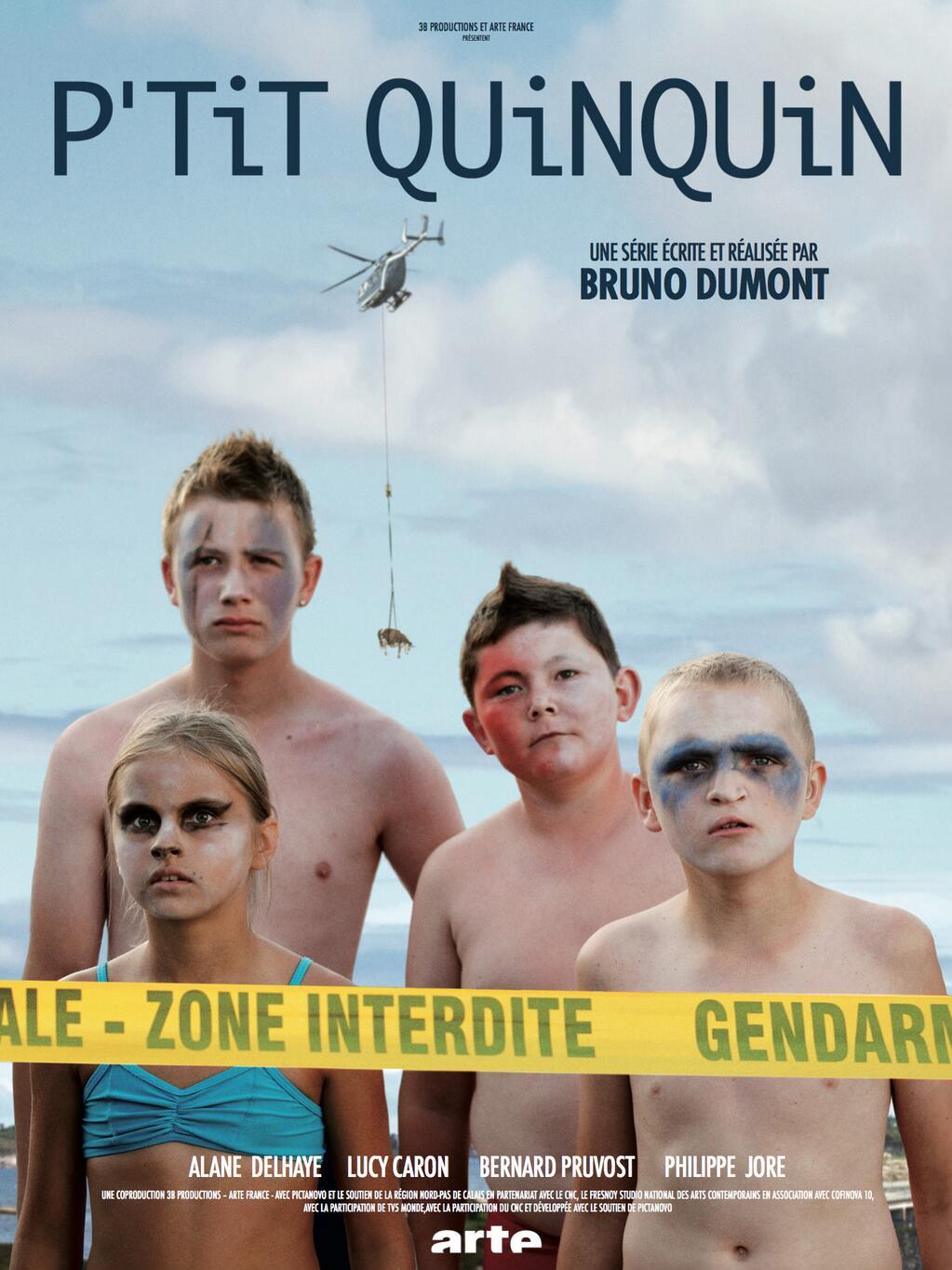

Reduced to its most simple elements (something about it has to be simple), Li'l Quinquin tells two adjacent stories, the first of which centers on Quinquin (Alane Delhaye), one of the chief ruffians in the tween population of a rural town in the north of France, with a primary focus on his youthful courtship of Eve Terrier (Lucy Caron), in those moments when he's not raising hell and hurling insults at the town's black Muslim family. The other story concerns Commandant Van der Weyden (Bernard Pruvost) of the local gendarmerie, and his lieutenant, Carpentier (Philippe Jore), and their investigation of a series of bizarre murders in which human bodies are being found, chopped into pieces, in the rectums of dead cows. Quinquin and his other little bad-news friends are on the scene when the first cow is airlifted out of a deep well where it seemingly can't have gotten to, and from that moment, he and Van der Weyden keep gliding past each other, to the commandant's annoyed frustration and the boy's sense of being unnecessarily bullied.

So, about that Twin Peaks comparison: herein, a quirky law enforcement agent who seems like an object of mocking comedy right up until it becomes clear just how nervily tuned-in to the moral and philosophical side of humanity he is, investigating a crime in which the odd inhabitants of a small town meander through space being their irrepressibly unique selves, and it becomes pretty clear pretty fast that the murder investigation, whatever is actually going, is really just a proxy for digging into the evil that happens in the presence of basic human decency, and because of the tacit approval of basically decent humans. As the lines of investigation keep cooling off, Van der Weyden suggests to Carpentier that it is, in fact, the Devil perpetrating these crimes, which is as good an explanation for any; the trick is that Li'l Quinquin prefers to situate the Devil someplace more human than metaphysical. Evil lies in how casually everyone talks about betraying their loved ones; evil lies in playing along with racism even when it feels wrong.

All of which ignores how absolutely hilarious the film is, which is, I am told, absolutely unheard of for this director. There's plenty of deadpan absurdity, and much uncomfortable, audience-indicting humor at the expense of the actors (most of them non-professional) and their strange, almost cartoon faces. Delhaye looks like a smudgy charcoal drawing or a hastily carved potato; Pruvost plays Van der Weyden as prone to wagging his eyebrows and bobbing his head, and it's deeply unclear whether these are the character's tics or the actors. Seeing these performers first shocks us into amusement; then, as we have time to get used to them, we're forced to reckon with that initial discomfort, as they all become more and more engaging and fascinating to look at for their expressiveness, not their strangeness (which is, I am told, entirely characteristic of this director).

For even while it's hard to see how funny the film is by look at its plot, it's hard to guess how richly human it is in thinking about how funny it is. Basically, the film twists itself every time you get think you get a handle on it, mixing violence and humanism, frivolous jokes with profound considerations of behavior. It's gorgeously shot by Guillaume Deffontaines, sharply etching every color of the buildings, sky, and land; yet it's entirely set among plain buildings and graffiti-coated slabs of ugly concrete. It has a vivid, living, involving soundscape made up of fuzzy, atonal singing and empty exteriors. The course of its plot is captivating even though virtually nothing happens in Van der Weyden's half of the story and literally nothing happens in Quinquin's. The characters are all beautifully tangible even though they're mostly awful people who behave like garish freaks. All of Li'l Quinquin feels like impossible contradictions stuffed into one box, and that gives it an unpredictable nature that makes the jokes funnier, the morality more piercing, the characters more alive. It is a marvelous, shaggy beast altogether, and while it's an overreach to call it the best film of any year, it's started 2015 off on the sturdiest footing.

Also, before I do that, it's worth spending a moment trying to categorise the thing that Li'l Quinquin is, as an object. It is a four-part television miniseries that aired in France in September, 2014, but that came some four months after its premiere at the 2014 Directors' Fortnight at Cannes, where it was screened as a single film clocking in at three hours and seventeen minutes. It screened in that form at the Toronto International Film Festival, and Cahiers du Cinéma named the film version as the best work of cinema of 2014, which is frankly enough for me. Particularly since it was shot in a TV-unfriendly widescreen aspect ratio that begs for a big screen and not the little online streaming bullshit that we in the United States get to enjoy, whether we're watching it in four chunks or one (it screened in New York for a week, but it's not news that New York cinephiles matter more than the rest of us). Yet even watching it in its guise as a feature film, the structure of the thing insists that we think of how it works as episodes, not a unified whole.

Regardless of what it technically is, Li'l Quinquin is an absolutely delightful experience, gathering bits and pieces of genres and styles until the act of trying to describe the feeling it imparts requires one of those 19-syllable German compound words. It's a bleak dark comedy, a police procedural, neorealist examination of the rhythm of childhood a study of morality, and a parable about racism in France; I can't do better than to call it a materialistic version of Twin Peaks that borrows its sense of humor from deadpan Scandinavian comedies and its overall tone from The 400 Blows, which means I can't do very well at all.

Reduced to its most simple elements (something about it has to be simple), Li'l Quinquin tells two adjacent stories, the first of which centers on Quinquin (Alane Delhaye), one of the chief ruffians in the tween population of a rural town in the north of France, with a primary focus on his youthful courtship of Eve Terrier (Lucy Caron), in those moments when he's not raising hell and hurling insults at the town's black Muslim family. The other story concerns Commandant Van der Weyden (Bernard Pruvost) of the local gendarmerie, and his lieutenant, Carpentier (Philippe Jore), and their investigation of a series of bizarre murders in which human bodies are being found, chopped into pieces, in the rectums of dead cows. Quinquin and his other little bad-news friends are on the scene when the first cow is airlifted out of a deep well where it seemingly can't have gotten to, and from that moment, he and Van der Weyden keep gliding past each other, to the commandant's annoyed frustration and the boy's sense of being unnecessarily bullied.

So, about that Twin Peaks comparison: herein, a quirky law enforcement agent who seems like an object of mocking comedy right up until it becomes clear just how nervily tuned-in to the moral and philosophical side of humanity he is, investigating a crime in which the odd inhabitants of a small town meander through space being their irrepressibly unique selves, and it becomes pretty clear pretty fast that the murder investigation, whatever is actually going, is really just a proxy for digging into the evil that happens in the presence of basic human decency, and because of the tacit approval of basically decent humans. As the lines of investigation keep cooling off, Van der Weyden suggests to Carpentier that it is, in fact, the Devil perpetrating these crimes, which is as good an explanation for any; the trick is that Li'l Quinquin prefers to situate the Devil someplace more human than metaphysical. Evil lies in how casually everyone talks about betraying their loved ones; evil lies in playing along with racism even when it feels wrong.

All of which ignores how absolutely hilarious the film is, which is, I am told, absolutely unheard of for this director. There's plenty of deadpan absurdity, and much uncomfortable, audience-indicting humor at the expense of the actors (most of them non-professional) and their strange, almost cartoon faces. Delhaye looks like a smudgy charcoal drawing or a hastily carved potato; Pruvost plays Van der Weyden as prone to wagging his eyebrows and bobbing his head, and it's deeply unclear whether these are the character's tics or the actors. Seeing these performers first shocks us into amusement; then, as we have time to get used to them, we're forced to reckon with that initial discomfort, as they all become more and more engaging and fascinating to look at for their expressiveness, not their strangeness (which is, I am told, entirely characteristic of this director).

For even while it's hard to see how funny the film is by look at its plot, it's hard to guess how richly human it is in thinking about how funny it is. Basically, the film twists itself every time you get think you get a handle on it, mixing violence and humanism, frivolous jokes with profound considerations of behavior. It's gorgeously shot by Guillaume Deffontaines, sharply etching every color of the buildings, sky, and land; yet it's entirely set among plain buildings and graffiti-coated slabs of ugly concrete. It has a vivid, living, involving soundscape made up of fuzzy, atonal singing and empty exteriors. The course of its plot is captivating even though virtually nothing happens in Van der Weyden's half of the story and literally nothing happens in Quinquin's. The characters are all beautifully tangible even though they're mostly awful people who behave like garish freaks. All of Li'l Quinquin feels like impossible contradictions stuffed into one box, and that gives it an unpredictable nature that makes the jokes funnier, the morality more piercing, the characters more alive. It is a marvelous, shaggy beast altogether, and while it's an overreach to call it the best film of any year, it's started 2015 off on the sturdiest footing.

Categories: comedies, crime pictures, french cinema, mysteries, serial killers, top 10