The last dance

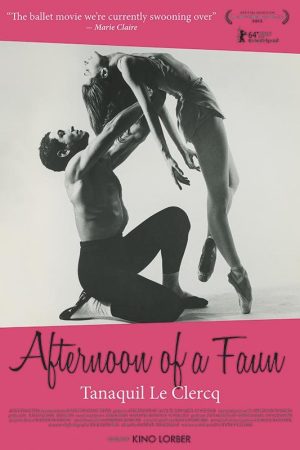

The biographical documentary Afternoon of a Faun: Tanaquil Le Clercq looks like a TV episode and has the generic structure of a TV episode, and what do you know? That's because it is an episode of the PBS documentary series American Masters, given some extra breathing room and a tiny theatrical release. So it feels a little bit unsporting to sink too much energy into talking shit about its aesthetic and structure, even though those elements are extraordinary problems with the film - crippling problems, even, as it goes deeper into its running time and further along in history.

Tanaquil Le Clercq (pronounced "luh clair"), for those who don't know - and that describes most of us, I am sure, which is exactly the blind spot the film is designed to redress - was one of the most important American ballet dancers of the 20th Century, a muse of the great choreographers George Ballanchine and Jerome Robbins, the former of whom she married, the latter of whom she held at arm's distance all her life. If we take the testimonials given by her various friends in the film at face value (and why not? PBS isn't noted for its sensationalised content), her elongated, rail-thin frame established a new paradigm in the body types and physical movements that dance would favor in the future, and this was the great legacy of her career, stopped short when she contracted polio at age 26.

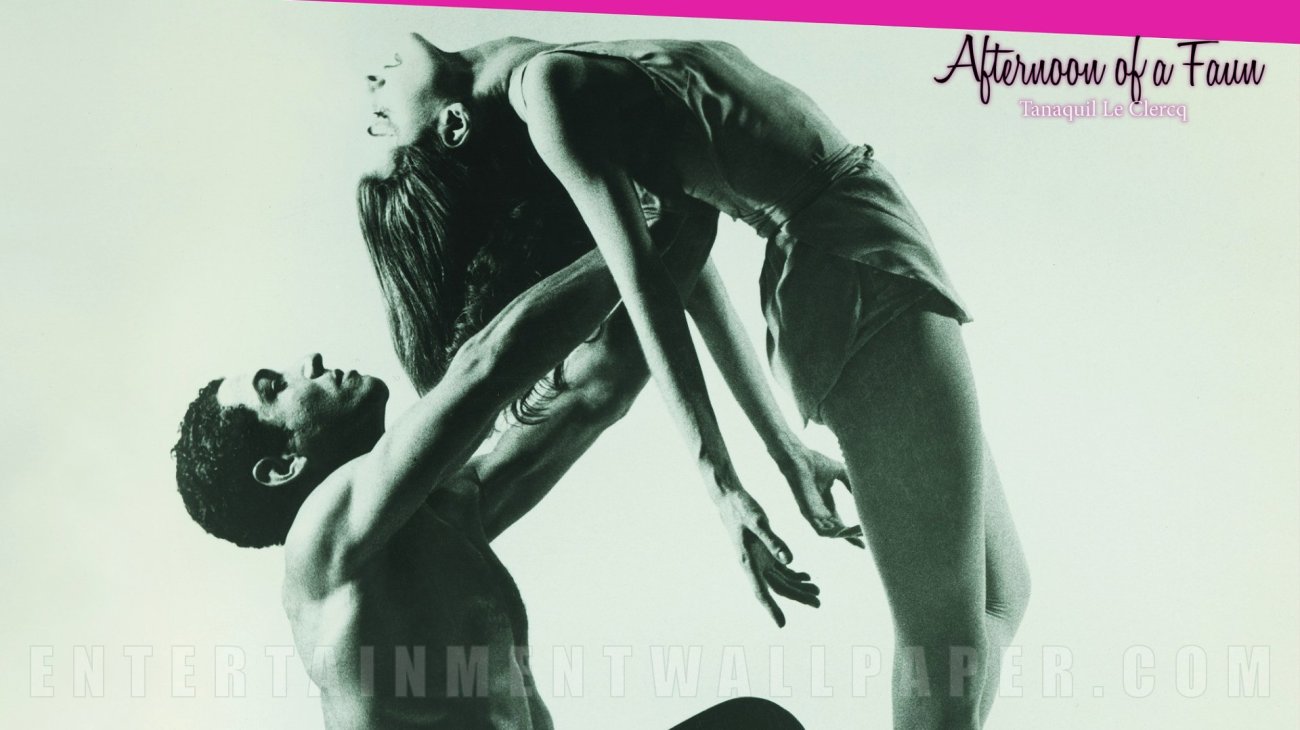

Afternoon of a Faun, named for a re-conceived Nijinsky ballet set to Debussy that Balanchine built around Le Clercq, tells its subject's life story in an extremely dry fashion, with personal remembrances delivered by people who knew and worked with her, arranged by director Nancy Buirski in straightforward, chronological order. Interrupting these stories are excerpts from Le Clercq and Robbins's letters, read by Marianne Bower and Michael Stuhlbarg, and this gives the movie a bit of deeper personality and texture than just hearing people relate the life story of their friend as, well, a history. Afternoon of a Faun is long on information, but low on insight: it does not succeed much at all in letting us get inside Le Clercq's head, since virtually all of its knowledge is provided by people who did not always quite see all the way inside the Le Clercq/Ballanchine marriage, apparently as difficult as any domestic situation involving two artists, one of them a man with a long history of short marriages, could manage to be. And since, following her illness, Le Clercq pulled away from the society of other humans for a great many years, leaving nobody that Buirski had access to with any real ability to speak to the crises faced by the dancer at that point in her life.

The documentary that results is lopsided and a bit frustrating, telling a story of a woman who had polio kind of happen at her rather than dig into what that illness meant. Perhaps there was no way around this, but the film's commitment to its basic, off-the-shelf talking heads construction certainly wouldn't yield any possibilities. Probably by design, Buirski has assembled a lecture, with all the facts laid out in neat, indisputable order, but not much of an emotional appeal, no matter how much the people who knew and obviously loved Tanny (as she is universally referred to by her intimates) express their affection in sweetly unguarded moments. And the carefully-researched feeling ends up spending so much time on context that for long stretches it feels more like the story of George Balanchine and his amazing successes with the lanky genius dancer he married that one time.

What picks the film up, and gives it some real cinematic appeal beyond the inherent interest of learning the basic facts of an artist whose skill and impact outweigh her limited name recognition, is the vintage material Buirski has assembled, whether in the form of an audio interview Le Clercq gave late in her life, reflecting with the wise detachment of an elegant, guarded lady of the upper class, or - much better still - in the footage of Balanchine's dances and Le Clercq especially from across her whole career. The chronological structure of the film means that almost all of this is frontloaded, and dries up right around the same time that the film starts to go slack and shallow in its treatment of her experiences. But while it's there, it elevates Afternoon of a Faun into the stratosphere. For there is a great deal of it, and it is cunningly woven in with the verbal reminiscences, and it reveals a dancer who is every bit the magnetic alien described by her eulogists. Without needing one scrap of historical context, Afternoon of a Faun makes all the argument it needs to for Le Clercq's brilliance simply through showing us Le Clercq in motion, for long, minimally-edited vintage sequences that have been gathering dust for God knows how long. The film would be valuable for collecting this footage and presenting it in a clear, well-organised way even if its lapses as documentary cinema and storytelling device were far more serious than they are.

There's nothing at all going on in the film that makes it recommend itself to anyone who isn't already mostly in the bag for this kind of thing: it assumes you already care about ballet, for one thing, and have a vested interest in learning about the politics and personal dramas of midcentury dance professionals. It assumes a PBS audience, in other words, and the limitations forced upon it by its inception are never questioned, let alone stretched. But for such a rudimentary, paint-by-numbers technique, Le Clercq does make for a good subject, and while Afternoon of a Faun isn't very much fun on any level, its content is interesting, and the woman at its center clearly worthy of greater attention. Given that providing that attention with minimal possible editorial distraction is all this film ever apparently wanted to do, it has to count as a success.

6/10

Categories: documentaries