Hollywood Century, 1988: In which the mindless destruction and brutality that have defined the 1980s in cinema attain artistic perfection

Speaking entirely personally, you understand, I'd be quick to identify the 1980s as the worst decade in the history of American filmmaking (though I recognise the strong argument in favor of giving that title to the 1960s, and frankly, the 2010s aren't heading in a very promising direction). It was a formulaic, money-driven, recklessly safe period in Hollywood, even conceding that Hollywood is always all of those things; and it certainly produced a smaller proportion of for-real masterpieces than any other time frame. But even here, in the pimpled ass-end of American cinema, there was one great shining beacon of light: the 1980s were maybe the single best period ever for English-language action film (and the "English-language" qualifier is possibly unnecessary, if the handful of '80s Hong Kong action films I've seen are representative). It was a perfect storm of things: the rejection by mainstream filmmakers of the philosophical and moral self-consciousness of the 1970s made it possible to tell simple stories of good guys fighting bad guys, the cultural conservatism that accompanied the Reagan Revolution provided fertile ground for telling stories of rugged all-American heroes triumphantly maintaining the status quo, the explosion of interest in special effects and visual effects in the wake of Star Wars allowed for more convincing and expansive explosions. Some of the action films of the day were great, and some of them were great while also being kind of lousy, and some were just unpleasant and terrible. But they had a sparkle that no action cinema before had possessed, and which action cinema since then has sought to replicate, to usually degraded effect. It was an age of exorbitant brutality and the finest hokey one-liners in the genre history; it was the greatest period of the Big, Dumb, Fun action movie.

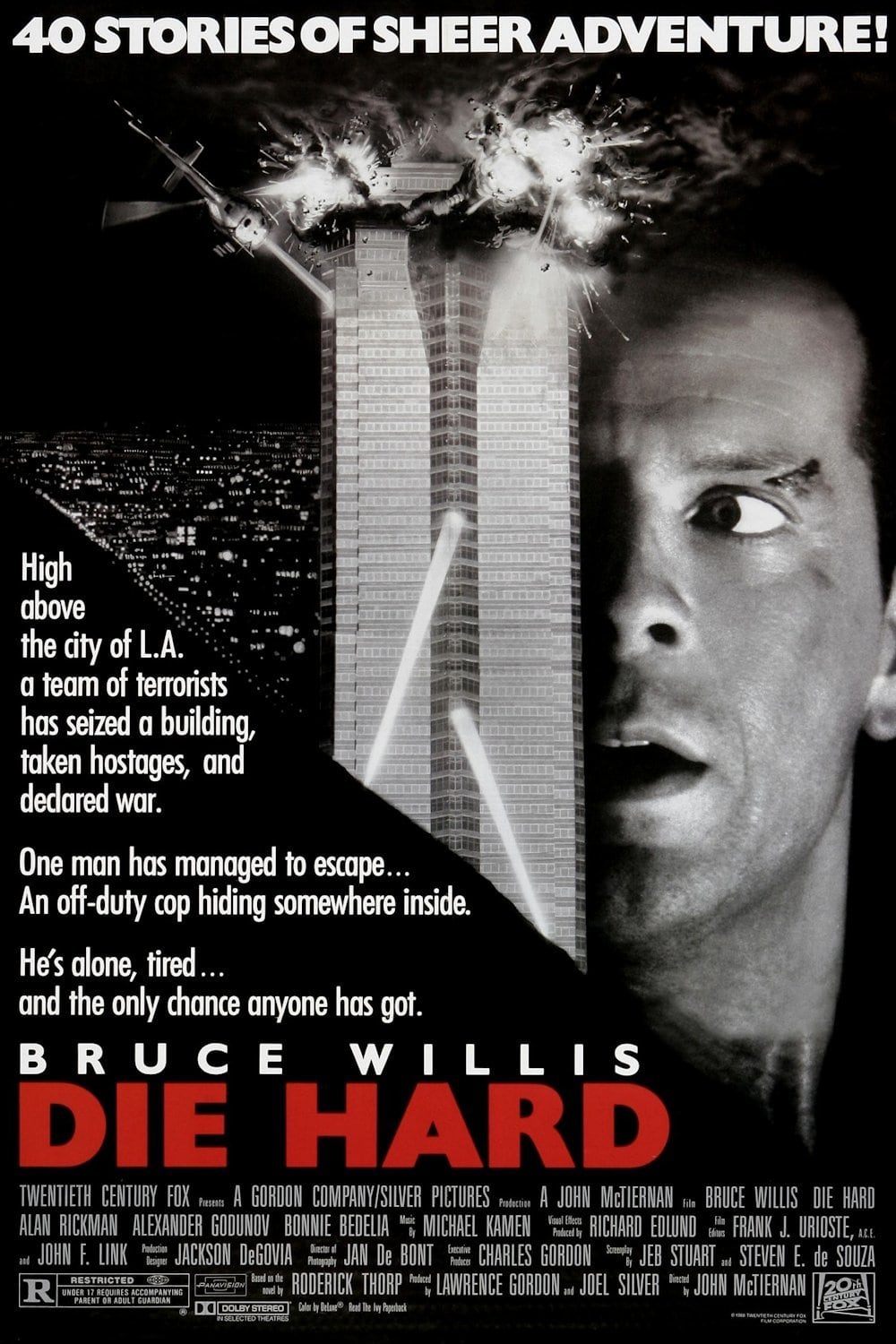

And it produced its finest work near the end, in 1988, with one of the handful of movies that can be fairly said to have completely overshadowed the entirety of their genre: Die Hard, a tony production released by 20th Century Fox, directed by John McTiernan of the great Arnold Schwarzenegger flick Predator from the year prior, with a script by first-timer Jeb Stuart and Steven E. de Souza, one of the key figures in the development of this particular strain of action cinema. Its influence can't be noted any more simply than by recalling that for a solid decade after, damn near every major action film released, whether it justified the comparison or not, was described as "Die Hard on a ____". Thus was not merely the impact of the film's terrifically effective, spare set-up, but also the degree to which it was already recognised as the exemplar of its form.

To begin with, Die Hard is a magnificent example of screenwriting discipline - I'm not exaggerating even a hair when I call it one of the most technically perfect screenplays of the whole decade. Everything that's in the film serves an extremely specific purpose, nothing is wasted, nothing is duplicated. If something is established in the first act, it will pay off later, even when it doesn't seem like it has to. There is, for example, the matter of a watch, introduced as symbol of the broken marriage at the heart of the film, and for a long time, it doesn't need to fill another purpose. And then, at the very end, it's called back for double duty: first to serve as a physical prop that fulfills a particular story need, second to round off the film's metaphorical reconstruction of that marriage. That's an obvious example, because it is foregrounded; but you cannot pick up any moment, even some of the most apparently tossed-off comic lines, that aren't there for a structural purpose. It's a miracle, like a building in which all of the ornate decoration is actually, upon closer inspection, revealed to be the raw girders, and what looks like garish Baroque messiness is in fact stripped-down Bauhaus severity. Which is a tremendously impressive feat for a film that was being re-written on the fly and frequently reliant on improvisation (see also: the equally flawless, equally jerry-rigged Casablanca)

Which is lovely for all the screenwriting students in the house, but mechanical perfection is only important if it's in service to anything else. And as a story, Die Hard is the most humane work of '80s action. Briefly (and befitting its high concept time, briefly is enough), the film tells of John McClane (Bruce Willis), a New York cop who arrives in Los Angeles on Christmas Eve, in the hopes of reconciling with his estranged wife, Holly Gennaro (Bonnie Bedelia). This requires him to show up at her company party celebrating a major Japanese-American business collaboration - this was near the end of the era when American business actually thought that Japan would be taking over the economy at any moment - in the sleek glass monster of a skyscraper known as Nakatomi Plaza (played by Fox Plaza, the studio's corporate headquarters). And he's not the only guest who probably shouldn't be there: this party is about to be crashed by a group of international terrorists led by Hans Gruber (Alan Rickman), whose radical political scheming is really just a blind for their actual goal, which is to steal a gratuitous quantity of money. McClane is the only person who's not immediately caught by the terrorists' first strike, making him the only person who can do anything to stop them.

And we have here the ingredients for a typical action fantasy (and, in fact, the film was first pitched as a sequel to Schwarzenegger's Commando), with two key shifts, both made because McTiernan decided to make some tweaks to the script. One of these is the introduction of the terrorists' actual, wholly mercenary motives. The other - which suits extremely well the casting of Willis, after a great deal of effort to find a more established action star - was to make McClane a bit of a clod and fairly overtly a dick (there is not one line in the script to suggest that Holly shares anything like the same responsibility for fucking up their marriage as he does, with his passive-aggressive alpha male posturing), and entirely fragile and human. He's capable of action movie stunts, of course, more than even a well-trained NYC cop could plausibly handle, but it takes a lot out of him: he gets pummeled, worn down, and scarred, and over the course of the film's one night (another McTiernan suggestion, apparently), we see all of that activity dragging him down. Not for nothing is one of the film's most iconic scenes his painful trek in bare feet across broken glass - it's a painful, permanent moment like you'd never see Schwarzenegger or Stallone or Norris experience.

The entirely physical, destructible hero, and the reduction of the conflict to, quite literally a cops & robbers scenario make Die Hard one of the most narrow, relatable action films of its generation. The stakes are not the free world; they're a disintegrating marriage. The hero isn't a mumble-mouthed tank; he's the slovenly quipster from the TV comedy Moonlighting. Everything about the film is calculated to bring it down to a level where it's not fantasy about larger-than-life supermen on the Bond model; it's a fantasy about Guys Like Us (and it is, one should admit at some point, a film entirely committed to a male audience; the best American action film it may be, but still bound by the rules of the American action film marketplace).

All this is what gives the film its surprisingly effective heart and emotional weight; it falls to the skills of McTiernan and his outstanding crew to express that heart in the context of one of the most exciting action thrillers ever made. Just as much as Die Hard has a perfectly constructed script, so is it perfectly made in all other ways; crisply edited by Frank J. Urioste and John F. Link with shots that communicate exactly what they have to in exactly the time it takes to communicate that (particularly in the marvelous, unshowy four-way crosscutting finale), punctuated by relentless, noisy, rousing sound design, buoyed by Michael Kamen's score, mixing generic action clichés with witty, playful insertions of snatches from traditional Christmas music, and nods to Beethoven's 9th symphony (yet another point insisted upon by McTiernan, who wanted to evoke Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange). The film has kineticism to spare, and a driving, building sense of space constricting and tension between characters escalating, enough so that its 132-minute running time, which by all rights should be offensively out-of-bounds for escapist genre fare like this, is over before it even begins to register (reliably, every time I watch the film, I'm dumbfounded that it's already 24 minutes in before the terrorists start to enact their plot, and the first hour especially seems over before the film is even done lacing its running shoes).

It's fluid, entirely momentum-based audio-visual storytelling at its very finest; there's not an ounce of fat on the movie, and the character-based material and the strictly action-oriented stunt and effects work are balanced so perfectly that it's hard to say whether this is a light drama about a man trying to be a better husband, incidentally punctuated by enormously loud gunshots; or if it's an action thriller that gets an unusual amount of mileage from the broad but insightful character sketches living inside of it. Either way, it's a masterpiece of populist filmmaking: every foot set right in order to make the most entertaining, immediately accessible film that the genius of McTiernan and company could manage to scrounge up. It's shallow in its goals, sure, but if every shallow film were this confident in the execution of all details from the smallest grace notes in lighting to the broadest scope of design and setting, and this rich in the iconic, almost mythic simplicity of its characters, I don't suppose that "shallow" would have much bite as a complaint.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1988

-Producer Steven Spielberg, director Robert Zemeckis, and the Walt Disney Company join forces to make the technically magnificent live-action/animation hybrid Who Framed Roger Rabbit

-Penny Marshall's fantasy Big is the first film directed by a woman to break $100 million at the U.S. box office

-Once upon a time, Mike Nichols's Working Girl is what mainstream feminism looked like

Elsewhere in world cinema in 1988

-Japan's Studio Ghibli releases a double feature to make your heart rise, with My Neighbor Totoro, and then crash into a thousand tear-stained fragments, with Grave of the Fireflies

-Pedro Almodóvar hits the international mainstream with the zany black comedy Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown

-George Sluizer's Dutch-French thriller The Vanishing pushes the psycho-thriller to new heights at the art house

And it produced its finest work near the end, in 1988, with one of the handful of movies that can be fairly said to have completely overshadowed the entirety of their genre: Die Hard, a tony production released by 20th Century Fox, directed by John McTiernan of the great Arnold Schwarzenegger flick Predator from the year prior, with a script by first-timer Jeb Stuart and Steven E. de Souza, one of the key figures in the development of this particular strain of action cinema. Its influence can't be noted any more simply than by recalling that for a solid decade after, damn near every major action film released, whether it justified the comparison or not, was described as "Die Hard on a ____". Thus was not merely the impact of the film's terrifically effective, spare set-up, but also the degree to which it was already recognised as the exemplar of its form.

To begin with, Die Hard is a magnificent example of screenwriting discipline - I'm not exaggerating even a hair when I call it one of the most technically perfect screenplays of the whole decade. Everything that's in the film serves an extremely specific purpose, nothing is wasted, nothing is duplicated. If something is established in the first act, it will pay off later, even when it doesn't seem like it has to. There is, for example, the matter of a watch, introduced as symbol of the broken marriage at the heart of the film, and for a long time, it doesn't need to fill another purpose. And then, at the very end, it's called back for double duty: first to serve as a physical prop that fulfills a particular story need, second to round off the film's metaphorical reconstruction of that marriage. That's an obvious example, because it is foregrounded; but you cannot pick up any moment, even some of the most apparently tossed-off comic lines, that aren't there for a structural purpose. It's a miracle, like a building in which all of the ornate decoration is actually, upon closer inspection, revealed to be the raw girders, and what looks like garish Baroque messiness is in fact stripped-down Bauhaus severity. Which is a tremendously impressive feat for a film that was being re-written on the fly and frequently reliant on improvisation (see also: the equally flawless, equally jerry-rigged Casablanca)

Which is lovely for all the screenwriting students in the house, but mechanical perfection is only important if it's in service to anything else. And as a story, Die Hard is the most humane work of '80s action. Briefly (and befitting its high concept time, briefly is enough), the film tells of John McClane (Bruce Willis), a New York cop who arrives in Los Angeles on Christmas Eve, in the hopes of reconciling with his estranged wife, Holly Gennaro (Bonnie Bedelia). This requires him to show up at her company party celebrating a major Japanese-American business collaboration - this was near the end of the era when American business actually thought that Japan would be taking over the economy at any moment - in the sleek glass monster of a skyscraper known as Nakatomi Plaza (played by Fox Plaza, the studio's corporate headquarters). And he's not the only guest who probably shouldn't be there: this party is about to be crashed by a group of international terrorists led by Hans Gruber (Alan Rickman), whose radical political scheming is really just a blind for their actual goal, which is to steal a gratuitous quantity of money. McClane is the only person who's not immediately caught by the terrorists' first strike, making him the only person who can do anything to stop them.

And we have here the ingredients for a typical action fantasy (and, in fact, the film was first pitched as a sequel to Schwarzenegger's Commando), with two key shifts, both made because McTiernan decided to make some tweaks to the script. One of these is the introduction of the terrorists' actual, wholly mercenary motives. The other - which suits extremely well the casting of Willis, after a great deal of effort to find a more established action star - was to make McClane a bit of a clod and fairly overtly a dick (there is not one line in the script to suggest that Holly shares anything like the same responsibility for fucking up their marriage as he does, with his passive-aggressive alpha male posturing), and entirely fragile and human. He's capable of action movie stunts, of course, more than even a well-trained NYC cop could plausibly handle, but it takes a lot out of him: he gets pummeled, worn down, and scarred, and over the course of the film's one night (another McTiernan suggestion, apparently), we see all of that activity dragging him down. Not for nothing is one of the film's most iconic scenes his painful trek in bare feet across broken glass - it's a painful, permanent moment like you'd never see Schwarzenegger or Stallone or Norris experience.

The entirely physical, destructible hero, and the reduction of the conflict to, quite literally a cops & robbers scenario make Die Hard one of the most narrow, relatable action films of its generation. The stakes are not the free world; they're a disintegrating marriage. The hero isn't a mumble-mouthed tank; he's the slovenly quipster from the TV comedy Moonlighting. Everything about the film is calculated to bring it down to a level where it's not fantasy about larger-than-life supermen on the Bond model; it's a fantasy about Guys Like Us (and it is, one should admit at some point, a film entirely committed to a male audience; the best American action film it may be, but still bound by the rules of the American action film marketplace).

All this is what gives the film its surprisingly effective heart and emotional weight; it falls to the skills of McTiernan and his outstanding crew to express that heart in the context of one of the most exciting action thrillers ever made. Just as much as Die Hard has a perfectly constructed script, so is it perfectly made in all other ways; crisply edited by Frank J. Urioste and John F. Link with shots that communicate exactly what they have to in exactly the time it takes to communicate that (particularly in the marvelous, unshowy four-way crosscutting finale), punctuated by relentless, noisy, rousing sound design, buoyed by Michael Kamen's score, mixing generic action clichés with witty, playful insertions of snatches from traditional Christmas music, and nods to Beethoven's 9th symphony (yet another point insisted upon by McTiernan, who wanted to evoke Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange). The film has kineticism to spare, and a driving, building sense of space constricting and tension between characters escalating, enough so that its 132-minute running time, which by all rights should be offensively out-of-bounds for escapist genre fare like this, is over before it even begins to register (reliably, every time I watch the film, I'm dumbfounded that it's already 24 minutes in before the terrorists start to enact their plot, and the first hour especially seems over before the film is even done lacing its running shoes).

It's fluid, entirely momentum-based audio-visual storytelling at its very finest; there's not an ounce of fat on the movie, and the character-based material and the strictly action-oriented stunt and effects work are balanced so perfectly that it's hard to say whether this is a light drama about a man trying to be a better husband, incidentally punctuated by enormously loud gunshots; or if it's an action thriller that gets an unusual amount of mileage from the broad but insightful character sketches living inside of it. Either way, it's a masterpiece of populist filmmaking: every foot set right in order to make the most entertaining, immediately accessible film that the genius of McTiernan and company could manage to scrounge up. It's shallow in its goals, sure, but if every shallow film were this confident in the execution of all details from the smallest grace notes in lighting to the broadest scope of design and setting, and this rich in the iconic, almost mythic simplicity of its characters, I don't suppose that "shallow" would have much bite as a complaint.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1988

-Producer Steven Spielberg, director Robert Zemeckis, and the Walt Disney Company join forces to make the technically magnificent live-action/animation hybrid Who Framed Roger Rabbit

-Penny Marshall's fantasy Big is the first film directed by a woman to break $100 million at the U.S. box office

-Once upon a time, Mike Nichols's Working Girl is what mainstream feminism looked like

Elsewhere in world cinema in 1988

-Japan's Studio Ghibli releases a double feature to make your heart rise, with My Neighbor Totoro, and then crash into a thousand tear-stained fragments, with Grave of the Fireflies

-Pedro Almodóvar hits the international mainstream with the zany black comedy Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown

-George Sluizer's Dutch-French thriller The Vanishing pushes the psycho-thriller to new heights at the art house

Categories: action, hollywood century, summer movies, thrillers, tis the season