The 50th Chicago International Film Festival

Screens at CIFF: 10/11 & 10/13

World premiere: 10 February, 2014, Berlin International Film Festival

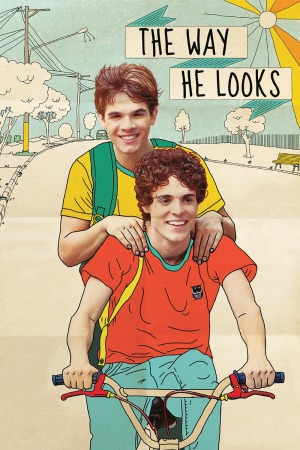

I will concede up front that to a certain type of viewer, and it is the type that I am, there's no way to describe Brazilian director Daniel Ribeiro's feature debut The Way He Looks that makes it sound tolerable. Or even to complete one sentence of plot description. "A blind, gay teen..." - nope. "In this study of the passive-aggressive awkwardness of high school courtship..." - nope. "Amid dappled shots of the afternoon sun, middle-class Brazilians..."- fuck, fuck, fuck, no.

Lucky for me, then, that The Way He Looks was as much an obligation to watch as a choice,* and I didn't get to just gloss over what turns out to be an exceptionally pleasant and beguiling film about adolescence. It makes no claims whatsoever to complexity or real creativity, but the execution of enormously predicable stock scenarios is so confident and beautiful, with such care and wisdom going into the creation of the characters, that artistic radicalism is hardly missed. There are some films that are completely worth seeing because they push against the edges of what the medium can do; there are some films that are worth seeing just because they're really well-made and emotionally resonant versions of a thing we've seen a hundred times, and will see a hundred more, just because they're pleasant and rewarding to watch. The Way He Looks may fall in the second category, but let's not miss the forest for the trees: the point of it is that it's still worth seeing.

Our blind, gay protagonist is Leo (Ghilherme Lobo), though it takes a little while before the film reveals to us (in an unforced, inductive way) that he can't see, and a great deal longer before it reveals that he likes boys. And this is because The Way He Looks is very eager, to its absolute credit, not interested in essentialising Leo in terms of his adjectives. It's also not even a little bit "boy realises he's gay, re-evaluates his personality, personal trauma ensues", which I also think is to its credit; finding out about his sexuality is about as complicated and traumatising as finding out by accident that he likes Thai food, and I admire how not-a-big-deal-ish the film, and its teenage characters, treat the topic, rather like their generation in reality has done compared to us older people. That kind of casual attitude towards sexuality is rare in movies still, and it's a heartening step forward to see a film that could be A Sociopolitical Statement play things so coolly.

But anyway, back to the plot: the key aspects of Leo's life are not his physical condition or his sexual appetite, but his shyness and withdrawn social life, fed by overly protective parents who are reluctant to let him do anything at all. His only friend to speak of is Giovana (Tess Amorim), a classmate he's known for years, and who has adopted the position of supportive big sister, urging him towards the openness and expression that he's been tamping down his whole life. And then, one day a new kid shows up in class: Gabriel (Fabio Audi, who is kind and a touch awkward himself, and who clings to Leo and Giovana as the nicest people around to help him find his footing. It turns out that he lives closer to Leo than Giovana does, and so it makes more sense for him to help Leo walk home; around the same time, a class project is assigned that the teacher demands must be carried out in same-sex teams. And thus it is that Leo and Gabriel spend almost all their out-of-school time together, while Leo and Giovana's relationship is strained like it never has been before, and that's even without the bit where Leo feels a connection to Gabriel of an entirely new sort. It's not clear if this is because he never realised he was gay, or because he never felt romantic attachment to someone, or if it's simply that, for the first time, he has a pleasurable secret that he can use as a mental release on the frustration of living with his hovering parents. What matters is that he has the sense of something wonderful and freeing lying in front of him for the first time.

The film is incredibly nice and gentle, and Lobo makes for an eminently likable protagonist whose gradual shift out of being painfully closed-in and shy is remarkably played and written: unlike most characters of the sort, whose arc involves becoming gregarious and dazzling free spirits, Leo is still a shy and quiet, just no so pained by it any more. Without any Big Gestures to play or Broad Arcs to tap into in the most obvious ways possible, Lobo's performance is far more internal and small: private smiles, a tendency to shrink himself down as he sits, and all little physical details that are subdued and quiet and intimate. It makes him more likable than an obviously Played and Scripted character could be; we have to quiet down with him to get to know him, rather than have the film splat things out, and it's far more rewarding.

All around Lobo's performance is a film that's entirely fine without being noticeably exciting. The other performances are good, but not revelatory in any real way, and while some of the compositions are striking in their geometry or their relationship with other images in the film, I got awfully tired of cinematographer Pierre de Kerchove's compulsion for romanticising the hell out of everything with soft golden sunlight. But it is nice to look at - oh, there's that word "nice" again. Well, "nice" is an okay thing for movies to be, and if they are going to be as nice as The Way He Looks, I am happy that they are also as honest and psychologically compelling.

7/10

World premiere: 10 February, 2014, Berlin International Film Festival

I will concede up front that to a certain type of viewer, and it is the type that I am, there's no way to describe Brazilian director Daniel Ribeiro's feature debut The Way He Looks that makes it sound tolerable. Or even to complete one sentence of plot description. "A blind, gay teen..." - nope. "In this study of the passive-aggressive awkwardness of high school courtship..." - nope. "Amid dappled shots of the afternoon sun, middle-class Brazilians..."- fuck, fuck, fuck, no.

Lucky for me, then, that The Way He Looks was as much an obligation to watch as a choice,* and I didn't get to just gloss over what turns out to be an exceptionally pleasant and beguiling film about adolescence. It makes no claims whatsoever to complexity or real creativity, but the execution of enormously predicable stock scenarios is so confident and beautiful, with such care and wisdom going into the creation of the characters, that artistic radicalism is hardly missed. There are some films that are completely worth seeing because they push against the edges of what the medium can do; there are some films that are worth seeing just because they're really well-made and emotionally resonant versions of a thing we've seen a hundred times, and will see a hundred more, just because they're pleasant and rewarding to watch. The Way He Looks may fall in the second category, but let's not miss the forest for the trees: the point of it is that it's still worth seeing.

Our blind, gay protagonist is Leo (Ghilherme Lobo), though it takes a little while before the film reveals to us (in an unforced, inductive way) that he can't see, and a great deal longer before it reveals that he likes boys. And this is because The Way He Looks is very eager, to its absolute credit, not interested in essentialising Leo in terms of his adjectives. It's also not even a little bit "boy realises he's gay, re-evaluates his personality, personal trauma ensues", which I also think is to its credit; finding out about his sexuality is about as complicated and traumatising as finding out by accident that he likes Thai food, and I admire how not-a-big-deal-ish the film, and its teenage characters, treat the topic, rather like their generation in reality has done compared to us older people. That kind of casual attitude towards sexuality is rare in movies still, and it's a heartening step forward to see a film that could be A Sociopolitical Statement play things so coolly.

But anyway, back to the plot: the key aspects of Leo's life are not his physical condition or his sexual appetite, but his shyness and withdrawn social life, fed by overly protective parents who are reluctant to let him do anything at all. His only friend to speak of is Giovana (Tess Amorim), a classmate he's known for years, and who has adopted the position of supportive big sister, urging him towards the openness and expression that he's been tamping down his whole life. And then, one day a new kid shows up in class: Gabriel (Fabio Audi, who is kind and a touch awkward himself, and who clings to Leo and Giovana as the nicest people around to help him find his footing. It turns out that he lives closer to Leo than Giovana does, and so it makes more sense for him to help Leo walk home; around the same time, a class project is assigned that the teacher demands must be carried out in same-sex teams. And thus it is that Leo and Gabriel spend almost all their out-of-school time together, while Leo and Giovana's relationship is strained like it never has been before, and that's even without the bit where Leo feels a connection to Gabriel of an entirely new sort. It's not clear if this is because he never realised he was gay, or because he never felt romantic attachment to someone, or if it's simply that, for the first time, he has a pleasurable secret that he can use as a mental release on the frustration of living with his hovering parents. What matters is that he has the sense of something wonderful and freeing lying in front of him for the first time.

The film is incredibly nice and gentle, and Lobo makes for an eminently likable protagonist whose gradual shift out of being painfully closed-in and shy is remarkably played and written: unlike most characters of the sort, whose arc involves becoming gregarious and dazzling free spirits, Leo is still a shy and quiet, just no so pained by it any more. Without any Big Gestures to play or Broad Arcs to tap into in the most obvious ways possible, Lobo's performance is far more internal and small: private smiles, a tendency to shrink himself down as he sits, and all little physical details that are subdued and quiet and intimate. It makes him more likable than an obviously Played and Scripted character could be; we have to quiet down with him to get to know him, rather than have the film splat things out, and it's far more rewarding.

All around Lobo's performance is a film that's entirely fine without being noticeably exciting. The other performances are good, but not revelatory in any real way, and while some of the compositions are striking in their geometry or their relationship with other images in the film, I got awfully tired of cinematographer Pierre de Kerchove's compulsion for romanticising the hell out of everything with soft golden sunlight. But it is nice to look at - oh, there's that word "nice" again. Well, "nice" is an okay thing for movies to be, and if they are going to be as nice as The Way He Looks, I am happy that they are also as honest and psychologically compelling.

7/10

Categories: brazilian cinema, ciff, love stories, south american cinema, teen movies