Summer of Blood: Lost and found

15 years after it was the talking point for a whole summer for both horror fans and people who did just about everything in their power to avoid horror, it's hard to judge The Blair Witch Project simply as a thing unto itself. But then again, it always was. When it was new, the film was mostly noteworthy for its extraordinarily aggressive ad campaign, including shameless TV specials promoting the wholly fictitious "true" story behind the movie, and for having what history customarily regards as the first major internet-based hype in the history of cinema advertising. These things very much tended to swamp the film in its first chance to hook up with audiences beyond the self-selecting confines of the Sundance Film Festival; and in the years since - especially since 2008 - it's had to also deal with being the progenitor of the "found footage" style of horror and, increasingly, every other genre as well, and if you can still find even a single person prone to any more forgiving judgment of that style than "considering that it was found footage, parts of it actually didn't suck", congratulations on having significantly more generous friends than I (and we must concede that the film didn't invent the found footage gimmick, though it's entirely possible that nobody involved in making it could have known that - the most important example, Cannibal Holocaust, was never a canonical film).

What's easy to forget, when "found footage" has long since come to mean "for no reason, this entire movie has been shot from the perspective of cameras, phones, security cameras, laptops, and God knows what, even when it takes entire subplots full of mountainous bullshit to keep that pointless gimmick going, I'm looking at you, Chronicle", the term actually came into being because The Blair Witch Project resembles footage, that was found. And then shown to us as evidence of what happened to the people who lost it. What was the last first-person movie to actually do that? Paranormal Activity 2? But this is not, anyway, Blair Witch's fault, any more than it would be fair to compliment it for not committing a sin that hadn't been invented yet.

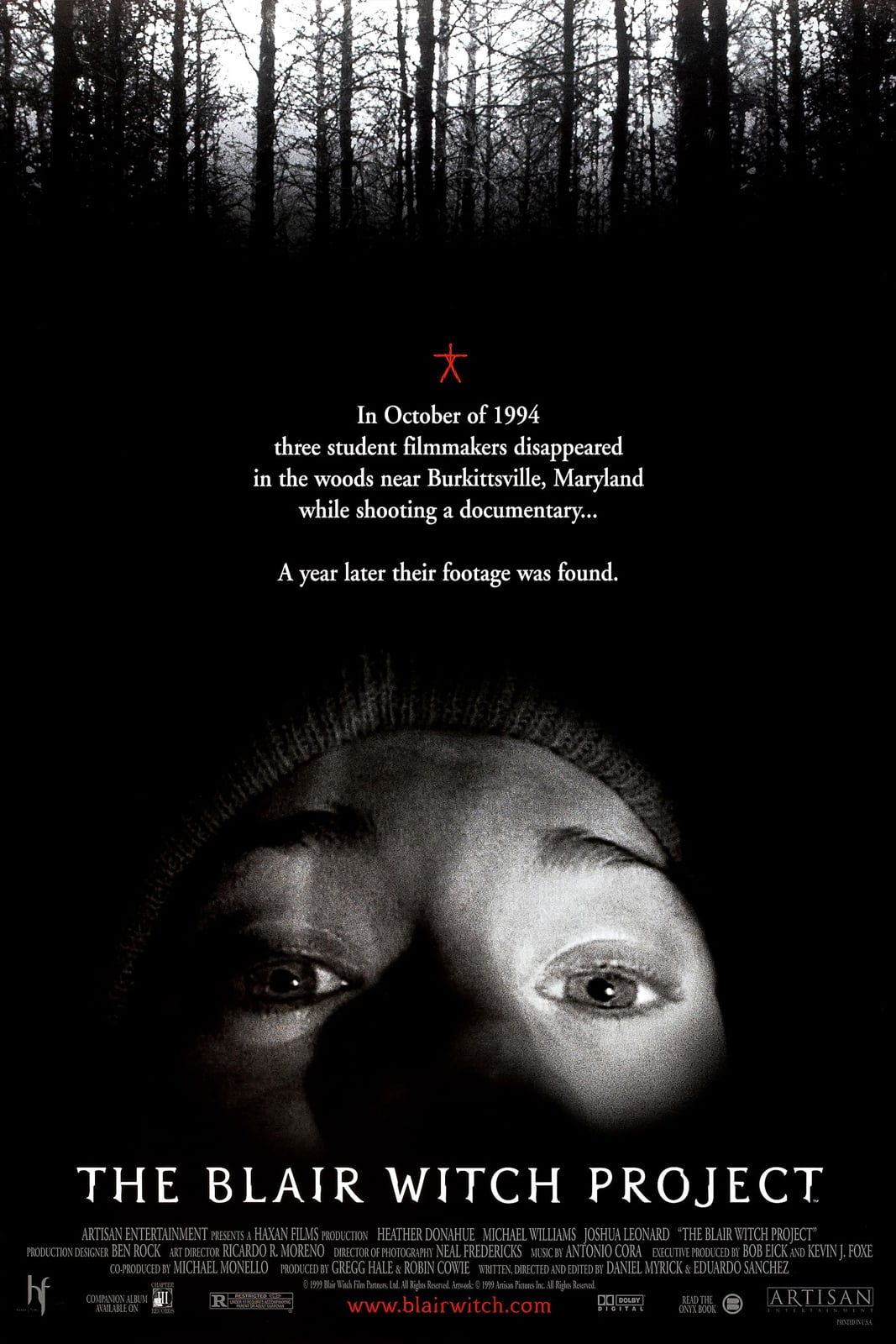

What's not easy to forget, if you lived through it, is that in 1999, this gimmick was used as the basis for one of the most shameless exercises in hucksterism that modern cinema has seen, as the folks at Artisan Entertainment used an array of tools that would have made William Castle fall down on his knees in a state of religious rapture to convince a surprising, and frankly alarming, number of people that The Blair Witch Project was the actual record of an actual documentary shoot that actually ended with the filmmakers actually missing and presumed actually dead. Or at least that the legend of the Blair Witch was a real piece of local folklore in the woods around the microscopic town of Burkittsville, Maryland. Neither of these facts are remotely true, which didn't stop Artisan from building the entire ad campaign around them. It worked, obviously: The Blair Witch Project was the highest-grossing independent production ever at the time of its release, and it remains the most profitable film in world history relative to its production cost.

All of this has always been enough to obscure the movie itself, whose not-inconsiderable merits are distinctly slight. The film is a spooky campfire story, pretty explicitly: the first quarter hour is spent collecting scary anecdotes from the Burkittsville populace, none of which actually clarify what the Blair Witch is, or even what the Blair Witch is perceived to be. But all of which suggest the uncanny and inexplicable in a terrifically beguiling way; without being expressly about death and danger in most cases, the stories all tell of something deeply unsettling and wrong that lives in the woods, something that you're much happier staying far away from. It's not scary, it's creepy, and a good sense of the really damn creepy is almost more pleasurable. For me, anyway; and I think the visceral division of the film into the "this is one of the scariest horror movies I've ever seen!" and "what the fuck, it's just a bunch of sticks!" camps is based on entirely that difference between creepiness and scariness.

At any rate, we get all of those stories in the first act of the film, and that provides the perfect backdrop for the rest, in which three student filmmakers - director Heather Donahue, sound recordist Mike Williams, and cameraman Josh Leonard (all three characters sharing the name with their actors) - go into the Burkittsville woods to make their documentary, from which those creepy interviews all came. We know, from an opening title card, that none of the three came out of the woods, nor was any trace found of them besides their footage, and that adds a pungent sense of doom to the footage, some of it clumsily assembled by barely-trained nonprofessionals (the three actors did virtually all of the filmmaking themselves), much of it hilariously overwrought - as a director, Donahue is much more excited about the heavy use of menacing innuendo than anything intellectually sober - and plenty of it just plain home movies, captured on video rather than the black and white 16mm footage of the "real" movie, in which three kids fuck around aimlessly with a camera. Knowing that the trio is slated to die, or vanish, or whatever, the footage of them doing nothing remotely interesting becomes keenly fascinating, in a lightly tragic way. No subsequent film has ever gotten more mileage out of using the audience's awareness that we're watching the first-person account of a terrible (fictitious) event as an element in giving that account added depth, interest, and meaning; while most films that invent styles are notable for how primitive they are, The Blair Witch Project really is the most involving and conceptually sound found footage movie ever made.

So the three filmmakers go into the woods, Donahue doggedly insisting that she's got a plan and a map, and film some of the creepy places where the creepiest evidence of the Evil Something was found, and the lingering atmosphere of those spooky stories from the first quarter hour, along with our knowledge that something happened, cast a lovely pall over the film, which starts to resemble a spooky campfire story all by itself. And eventually, the trio's sense that something is Out There In The Woods begins to bubble up, and the cracks and rustling and footpads that happen any time you're out in the wild with deer and squirrels and all start to sound a bit more deliberate and a bit more humanoid, and that's when the little rock piles and stick figures start appearing. Along with, at night, noises that sound far too deliberate to just be nocturnal animals milling around, but also don't plausibly sound like the work of pranksters from Burkittsville, unless the entire town, babies and all, has crept into the woods just to antagonise three film students.

And it's exactly as the film starts to ramp up its paranormal activities that I find The Blair Witch Project starts to lose gas. Technical limitations have a lot to do with it: the low-fi film, aping an even lower-fi shoot (the video footage was altered in post-production to look worse, since it was meant to take place in 1994 and the quality of the digital cameras used to shoot it didn't exist at that point), isn't entirely up to the task of replicating the sounds and images that the trio hears. "Was that a baby?" they panic; "was that a cackle? What are those noises surrounding us from all sides?" And the simple fact is that it's hard to hear what they're hearing through the puffy static: there' noise and sticks cracking, all right, but the implicit sense of overbearing sound from all sides of the dark woods isn't there for us. The lengthy stretches of pitch black footage, sometimes with charcoal grey figures moving around in it, doesn't accurately mimic the human eye's ability to see in even the darkest night outdoors. That the actors, given no sense of what the filmmakers were going to do to torment them during the weeklong camping trip/film shoot, are authentically scared, and a lot of that bleeds off the screen. But the specific stimuli that freak them the hell out just doesn't always translate.

Then there's the other thing, the frequent complaint that the film just depicts three idiots wandering around the woods, lost. Which it does, and they are: not that any of us know what it's like to be trapped in a forest with a malevolent inhuman entity, but the students' basic wilderness survival skill set is abysmally low, yet high enough that they never risk starving to death on a trip that ends up taking twice as long as they'd planned for. And after the halfway mark, the film undeniably gets repetitive: walk around all day, the boys getting increasingly angry towards Donahue, who responds by being haughty and defensive, see a couple of things that are inexplicable and weird and creepy, and then endure noises and tent-shaking at night. One gets the impression that the film could have gone on for six hours or stopped at the 50-minute mark (it is, instead, 80), without having meaningfully changed the rhythm of the daily storytelling formula. That it descends into backbiting and frantic shouting I do not hold against it: the three actors are responding in the way that I think most of us would, both to the events within the film and to the stressful way that the film was made. That it does so in a redundant way is unforgivable.

At any rate, enough of this transpires eventually that the film shifts into its honestly confusing final sequence, in a spooky old building deep in the woods, and the cinematography starts to become infamously shaky (though, with a generation of shakycam features descended from it, The Blair Witch Project honestly looks mostly sedate these days), and the film stops on a moment of startling ambiguity. The finale is, by itself, not very great, though at the point it arrives, anything that's not more "walk in the woods, fight, be scared" is welcome, and I'm tremendously glad that the film doesn't explain a goddamn thing: it just shows that whatever Evil Something has been haunting those woods is still there, and can't be explained now any more than it has been for the last 200 years. The abrupt, unforgiving way the film ends is still shocking despite all the film's imitators, and it's a strong finish to a film that spends a little too much time wandering, giving the whole thing the feeling of more impact than it might have otherwise had.

The film's chief success, though, was never going to be in the individual execution of that or this moment, but in its concept; it's gimmick, if you'd rather be harsh on the results. Director-writers Daniel Myrick & Eduardo Sánchez (who, like the actors, proved surprisingly unable to transform the film's enormous success into subsequent careers of any scale or merit) hit upon a great idea to put us, the audience, into a ghost story, something that had never been done with anything like this much success. The whole movie is built around that: the opening sequence is by far the most conventionally cinematic, giving us background so that we know what story we're going to be dropped into; the rest then shifts into raw, first-person footage that resembled nothing that mainstream filmmaking had ever scene at the time of the film's production, and the way that it feels like we're being involved in the footage, taking part in the process of discovery and forced to make the same assumptions as the characters, made for an interactive horror movie like nothing before it - and very little after it, truth be told; most found-footage movies have copied the surface of The Blair Witch Project but not the soundness of its concept nor the aesthetic cohesion of its execution. I don't know if it's my fault or the film's that I consistently lose interest in its efforts well before the end, but as a bravura concept and such a well-crafted execution of that concept that it still hasn't been improved upon, I admire it even in the moments when I'm enjoying it least.

Body Count: Maybe 3, maybe 0. No trace of them was ever found, after all.

What's easy to forget, when "found footage" has long since come to mean "for no reason, this entire movie has been shot from the perspective of cameras, phones, security cameras, laptops, and God knows what, even when it takes entire subplots full of mountainous bullshit to keep that pointless gimmick going, I'm looking at you, Chronicle", the term actually came into being because The Blair Witch Project resembles footage, that was found. And then shown to us as evidence of what happened to the people who lost it. What was the last first-person movie to actually do that? Paranormal Activity 2? But this is not, anyway, Blair Witch's fault, any more than it would be fair to compliment it for not committing a sin that hadn't been invented yet.

What's not easy to forget, if you lived through it, is that in 1999, this gimmick was used as the basis for one of the most shameless exercises in hucksterism that modern cinema has seen, as the folks at Artisan Entertainment used an array of tools that would have made William Castle fall down on his knees in a state of religious rapture to convince a surprising, and frankly alarming, number of people that The Blair Witch Project was the actual record of an actual documentary shoot that actually ended with the filmmakers actually missing and presumed actually dead. Or at least that the legend of the Blair Witch was a real piece of local folklore in the woods around the microscopic town of Burkittsville, Maryland. Neither of these facts are remotely true, which didn't stop Artisan from building the entire ad campaign around them. It worked, obviously: The Blair Witch Project was the highest-grossing independent production ever at the time of its release, and it remains the most profitable film in world history relative to its production cost.

All of this has always been enough to obscure the movie itself, whose not-inconsiderable merits are distinctly slight. The film is a spooky campfire story, pretty explicitly: the first quarter hour is spent collecting scary anecdotes from the Burkittsville populace, none of which actually clarify what the Blair Witch is, or even what the Blair Witch is perceived to be. But all of which suggest the uncanny and inexplicable in a terrifically beguiling way; without being expressly about death and danger in most cases, the stories all tell of something deeply unsettling and wrong that lives in the woods, something that you're much happier staying far away from. It's not scary, it's creepy, and a good sense of the really damn creepy is almost more pleasurable. For me, anyway; and I think the visceral division of the film into the "this is one of the scariest horror movies I've ever seen!" and "what the fuck, it's just a bunch of sticks!" camps is based on entirely that difference between creepiness and scariness.

At any rate, we get all of those stories in the first act of the film, and that provides the perfect backdrop for the rest, in which three student filmmakers - director Heather Donahue, sound recordist Mike Williams, and cameraman Josh Leonard (all three characters sharing the name with their actors) - go into the Burkittsville woods to make their documentary, from which those creepy interviews all came. We know, from an opening title card, that none of the three came out of the woods, nor was any trace found of them besides their footage, and that adds a pungent sense of doom to the footage, some of it clumsily assembled by barely-trained nonprofessionals (the three actors did virtually all of the filmmaking themselves), much of it hilariously overwrought - as a director, Donahue is much more excited about the heavy use of menacing innuendo than anything intellectually sober - and plenty of it just plain home movies, captured on video rather than the black and white 16mm footage of the "real" movie, in which three kids fuck around aimlessly with a camera. Knowing that the trio is slated to die, or vanish, or whatever, the footage of them doing nothing remotely interesting becomes keenly fascinating, in a lightly tragic way. No subsequent film has ever gotten more mileage out of using the audience's awareness that we're watching the first-person account of a terrible (fictitious) event as an element in giving that account added depth, interest, and meaning; while most films that invent styles are notable for how primitive they are, The Blair Witch Project really is the most involving and conceptually sound found footage movie ever made.

So the three filmmakers go into the woods, Donahue doggedly insisting that she's got a plan and a map, and film some of the creepy places where the creepiest evidence of the Evil Something was found, and the lingering atmosphere of those spooky stories from the first quarter hour, along with our knowledge that something happened, cast a lovely pall over the film, which starts to resemble a spooky campfire story all by itself. And eventually, the trio's sense that something is Out There In The Woods begins to bubble up, and the cracks and rustling and footpads that happen any time you're out in the wild with deer and squirrels and all start to sound a bit more deliberate and a bit more humanoid, and that's when the little rock piles and stick figures start appearing. Along with, at night, noises that sound far too deliberate to just be nocturnal animals milling around, but also don't plausibly sound like the work of pranksters from Burkittsville, unless the entire town, babies and all, has crept into the woods just to antagonise three film students.

And it's exactly as the film starts to ramp up its paranormal activities that I find The Blair Witch Project starts to lose gas. Technical limitations have a lot to do with it: the low-fi film, aping an even lower-fi shoot (the video footage was altered in post-production to look worse, since it was meant to take place in 1994 and the quality of the digital cameras used to shoot it didn't exist at that point), isn't entirely up to the task of replicating the sounds and images that the trio hears. "Was that a baby?" they panic; "was that a cackle? What are those noises surrounding us from all sides?" And the simple fact is that it's hard to hear what they're hearing through the puffy static: there' noise and sticks cracking, all right, but the implicit sense of overbearing sound from all sides of the dark woods isn't there for us. The lengthy stretches of pitch black footage, sometimes with charcoal grey figures moving around in it, doesn't accurately mimic the human eye's ability to see in even the darkest night outdoors. That the actors, given no sense of what the filmmakers were going to do to torment them during the weeklong camping trip/film shoot, are authentically scared, and a lot of that bleeds off the screen. But the specific stimuli that freak them the hell out just doesn't always translate.

Then there's the other thing, the frequent complaint that the film just depicts three idiots wandering around the woods, lost. Which it does, and they are: not that any of us know what it's like to be trapped in a forest with a malevolent inhuman entity, but the students' basic wilderness survival skill set is abysmally low, yet high enough that they never risk starving to death on a trip that ends up taking twice as long as they'd planned for. And after the halfway mark, the film undeniably gets repetitive: walk around all day, the boys getting increasingly angry towards Donahue, who responds by being haughty and defensive, see a couple of things that are inexplicable and weird and creepy, and then endure noises and tent-shaking at night. One gets the impression that the film could have gone on for six hours or stopped at the 50-minute mark (it is, instead, 80), without having meaningfully changed the rhythm of the daily storytelling formula. That it descends into backbiting and frantic shouting I do not hold against it: the three actors are responding in the way that I think most of us would, both to the events within the film and to the stressful way that the film was made. That it does so in a redundant way is unforgivable.

At any rate, enough of this transpires eventually that the film shifts into its honestly confusing final sequence, in a spooky old building deep in the woods, and the cinematography starts to become infamously shaky (though, with a generation of shakycam features descended from it, The Blair Witch Project honestly looks mostly sedate these days), and the film stops on a moment of startling ambiguity. The finale is, by itself, not very great, though at the point it arrives, anything that's not more "walk in the woods, fight, be scared" is welcome, and I'm tremendously glad that the film doesn't explain a goddamn thing: it just shows that whatever Evil Something has been haunting those woods is still there, and can't be explained now any more than it has been for the last 200 years. The abrupt, unforgiving way the film ends is still shocking despite all the film's imitators, and it's a strong finish to a film that spends a little too much time wandering, giving the whole thing the feeling of more impact than it might have otherwise had.

The film's chief success, though, was never going to be in the individual execution of that or this moment, but in its concept; it's gimmick, if you'd rather be harsh on the results. Director-writers Daniel Myrick & Eduardo Sánchez (who, like the actors, proved surprisingly unable to transform the film's enormous success into subsequent careers of any scale or merit) hit upon a great idea to put us, the audience, into a ghost story, something that had never been done with anything like this much success. The whole movie is built around that: the opening sequence is by far the most conventionally cinematic, giving us background so that we know what story we're going to be dropped into; the rest then shifts into raw, first-person footage that resembled nothing that mainstream filmmaking had ever scene at the time of the film's production, and the way that it feels like we're being involved in the footage, taking part in the process of discovery and forced to make the same assumptions as the characters, made for an interactive horror movie like nothing before it - and very little after it, truth be told; most found-footage movies have copied the surface of The Blair Witch Project but not the soundness of its concept nor the aesthetic cohesion of its execution. I don't know if it's my fault or the film's that I consistently lose interest in its efforts well before the end, but as a bravura concept and such a well-crafted execution of that concept that it still hasn't been improved upon, I admire it even in the moments when I'm enjoying it least.

Body Count: Maybe 3, maybe 0. No trace of them was ever found, after all.