Hollywood Century, 1968: In which we greet the new age of sinewy action movies with sinewy action stars

1968 is a symbolically freighted year in the history of American filmmaking, for it was in 1968 that the Motion Picture Association of America, two years into the nearly four-decade tenure of president Jack Valenti, abolished the Production Code that had been zealously enforced (though increasingly less so) ever since 1934. In place of the mandatory rules of the Code, the MPAA now introduced a four-tier rating system (later increased to five-tier), which officially took effect on 1 November.

It was an open admission by the establishment that American cinema had, over the course of 34 years of de facto censorship, been steadily losing ground in its ability to depict stories that reflected the content of real life and to express the full range of human experiences and thoughts. It triggered a sudden expansion of possibilities that lead to a flurry of studio-backed and independent filmmaking between 1969 and 1975 or so that bore witness to widespread creativity and experimentation that has only existed a few times in the history of American cinema.

This leaves '68 as something of a transitional year, when old-style Hollywood was still puttering to a close while what was not yet called the New Hollywood Cinema hadn't started to coalesce as any kind of clear movement. It's kind of an irresistible metaphor, if an appallingly shallow one, for a year that ranks among the most chaotic in modern history: the increasing fervor of the anti-war protests, along with high-profile political assassinations, the high water mark of the visibility of hippie culture, and the last screaming gasps of organised racism in the form of George Wallace's last presidential run, all served to put the United States in a state of near-madness that it hasn't experienced in any other single calendar year since the end of World War II. And the U.S. wasn't even particularly noteworthy for its social upheavals compared to the revolutionary activity sweeping through Europe at the same time.

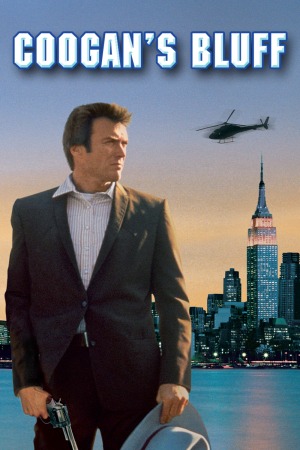

It's all enough to make movies seem very silly and irrelevant, especially since the long lead time on film production means that nothing released in '68 could engage with that social chaos in its complet scope, or fully explore the new freedoms of post-Code Hollywood. But discussing movies is precisely what we're here to do, so however narrow and unhelpful a window it provides into the world at that time, let us turn now to Coogan's Bluff, a film that combines unabashed conservatism with ebullient liberalism and thus does the best job I could come up with of embodying all the tensions, both social and aesthetic, of that definitive year. It is, along with the same year's better-known Bullitt, a cop action movie that feels astonishingly ahead of its time: based on the urban grittiness of the mise en scène, the blanched feeling to the cinematography, and especially the Lalo Schifrin score (another trait the film shares with Bullitt), in the third year of that composer's prominence as a creator of funk-touched jazz, it would be easy to assume that the film was from the early '70s.

In fact, there's very little aesthetically to clearly differentiate it from 1971's Dirty Harry, the ur-action film of the 1970s. Particularly since it shares with Dirty Harry director Don Siegel and star Clint Eastwood (as well as co-writer Dean Riesner, whose work I gather to have largely consisted of following Eastwood's orders), making it something of a dry run for that later, better, and better-known celebration of fascism. They share a thematic wheelhouse: hardass cop who gets the job done runs afoul of bureaucracy and the weirdos of the counterculture. They look virtually identical: Coogan's Bluff was shot by Bud Thackeray, and Dirty Harry by Bruce Surtees, but both have that flat browned-over look that stamps so many movies as coming out in that era. Coogan's Bluff is a bit less tough than its successor: it's not nearly as violent, has less action overall (really, just a climactic chase sequence), and a considerably sunnier sense of humor, though the list of films that are funnier than Dirty Harry is awfully long.

It's altogether a wiry, tense little bundle of energy, a perfect example of Sigel's talent for creating lean, merciless action films and thrillers. It was the first film he and Eastwood made together, in a tremendously important professional relationship that resulted in five absolutely quintessential titles in both men's filmographies (or at least four plus the comic Western Two Mules for Sister Sara, the obvious "one of these things is not like the others" title among their collaborations), and cast a shadow over Eastwood's own directorial efforts from which he didn't fully emerge until at least the mid-'80s, if indeed he ever has.

The film finds Eastwood playing Coogan, an Arizona deputy sheriff tasked with heading to New York to bring back escaped killer James Ringerman (Don Stroud, when we eventually see him), currently in NYPD custody. Upon arriving on the East Coast, Coogan devotes all of his energy to leaving again as soon as possible, with his irritated attitude getting him nowhere with the stubborn Lt. McElroy (Lee J. Cobb), who acts with deliberate slowness in helping Coogan through the paper-pushing necessary to extradite Ringerman, currently recovering from a bad LSD trip in hospital under police watch. Eventually, Coogan's impatience causes him to cheat the system to get to Ringerman faster, but this has the unfortunate side effect of putting the fugitive in a perfect position to escape from Coogan, meaning that the Arizona lawman now has to dive right into the messiness of New York life in order to get his quarry back.

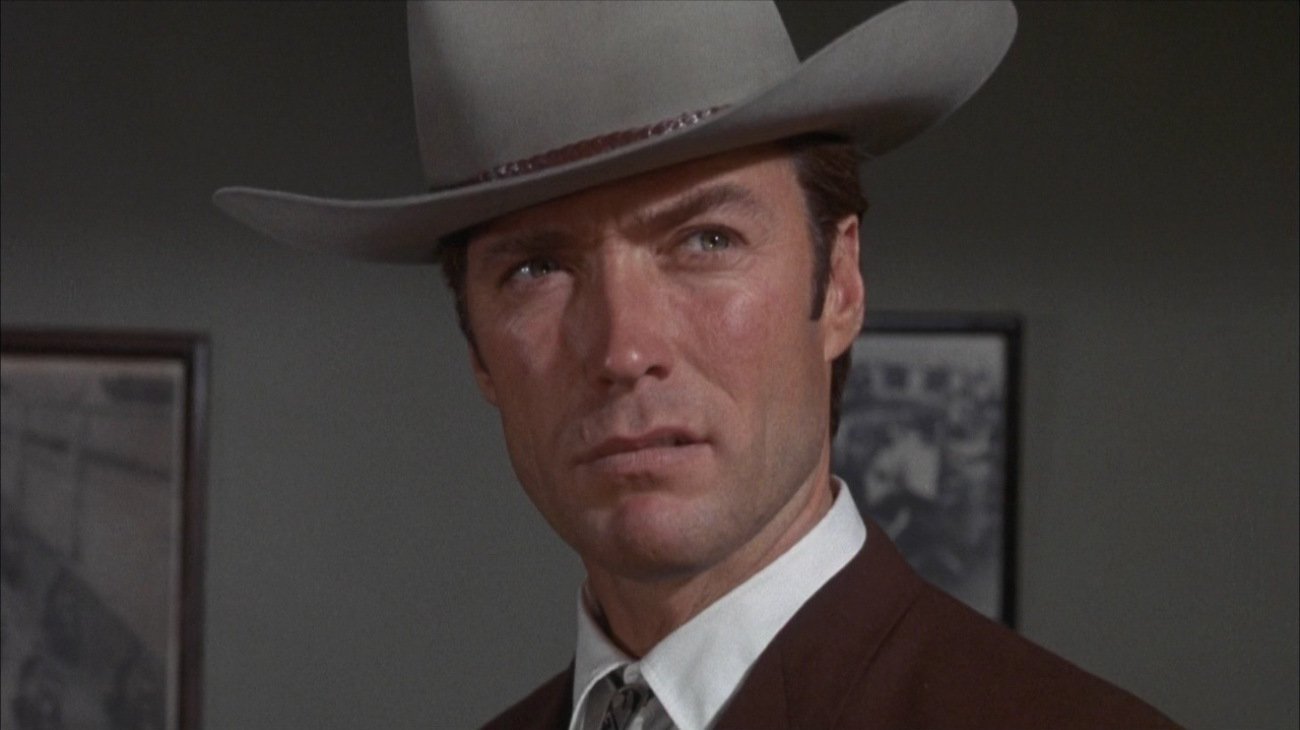

There's no better place to start with the film's every-which-way morality than with Coogan himself, a character who clearly fucks up in a way that the film never exonerates him for, and yet we're so clearly meant to identify with him and his befuddled anger at the wall of bureaucracy driving the New York police that it's also never the case that he's pointed out to be in the wrong at any moment. Part of that, undoubtedly, is the basic fact that Coogan was being played by Eastwood, right in the thick of his "hot new movie star" days - two years after The Good, the Bad and the Ugly sealed the deal on turning him into an icon, a performer who automatically reads as 'the good guy" regardless of whether or not the scrip surrounding him concurs. Even as the film treats his Southwestern badassery with a certain detached amusement at the corny incongruity of a taciturn cowboy-hero parading around in the 1960s, it also sides with him against the haughty New Yorkers so attached to their fast-paced city living that they call out that same corniness.

Similarly, the film's depiction of New York in the countercultural age splits a weird difference between trying its best to depict the energy and openness of that era, with the alarmed confusion of someone who will never be part of that world and doesn't want to. There's a sequence set in a club - I am not certain at all if it's the club, the house band, or both that are named Pigeon-Toed Orange Peel, but that name appears in giant neon with a theme song playing underneath scenes of stoners and drop-outs and radicals dancing around in brightly colored insanity. It is one of the great overwrought "what the fuck, New York?" scenes of the decade, depicting the nightmare that straitlaced Midwesterners have about Those People, far more than I suspect it depicts anything that ever actually existed. But even if the depiction is crazy paranoia, the tone is far more muted and sedate: Coogan seems entirely unruffled by what's going on around him, and the film that actively clings to his perspective has no choice but to follow suit. Instead of gawking at the freaks, the film simply depicts them, indulging in its ability to show drug use and nudity much as it indulges in the cruel efficiency of Coogan the law enforcer, edgy in a way that no American film released prior to 1967 would have been permitted.

The film's attempt to have its cake and eat it too could easily look like rank cynicism, except that I'm reasonable confident that it's a side effect of the film's actual function and purpose, which have nothing do with themes about The Way The World Is, as much fun as it is to read those themes into it (it is, anyway, far more rewarding and revealing to piece together society's self-analysis through films that aren't doing it on purpose, and thus can't be willfully picking and choosing what they represent). There's never a moment of Coogan's Bluff where it ever ceases to resemble a Don Siegel film, and Siegel as a director was driven by a desire to ruthlessly and efficiently tell thrilling stories with every possible piece of extraneous material carved away. He is as close as American cinema has produced to Ernest Hemingway: a superlatively masculine artist for whom blunt, unpoetic directness is privileged above all other things. The focus here is on Coogan and his process: everything that contributes to that is kept in and everything that gets in the way is jettisoned, leaving a freakishly slender, direct cop picture. There's an immediate clarity to the shots, composed and blocked and cut together not to imply secret depths or emotional currents, but to present the physical places of the movie with unblinking presence, and to watch the characters doing exactly what they have to do. It is not a film of inner lives: even Coogan's weirdly persistent womanising, maybe the most dated element of the film (I am totally unable to parse its sexual politics, I must confess), speaks less to his sexual appetites or his virility, than his pragmatism in manipulating people to help to his ends. This might be the sleekest Siegel film I have seen, which isn't all the same as calling it the best: frankly, its mechanical precision gets to be a little alienating, and even Dirty Harry feels like it has real people in a way that this film frequently doesn't. It's wry, persistent sense of humor is a godsend: without frequent touches of light irony, Coogan's Bluff could easily pivot into being genuinely unpleasant.

Instead, it's a satisfying police yarn with some really great, physically hefty location photography, and a fine star turn by Eastwood before he'd begun to really massage his persona into something more than a sardonic badass. I imagine it might have seemed more impressive in '68 than it does now: it's no-bullshit city thriller attitude was far rarer then, and many of the films in more or less the same mode in over the next few years are certainly more impressive on the level of characterisation and world-building. But Coogan's Bluff is a taut entertainment in its own right. And while it has neither the depth nor complexity that many of its descendants do, it came out early enough that the world it depicts feels totally different than any of them. It looks and acts like a '70s movie, but it is a '60s movie, and the tension that feeds, especially filtered through Siegel and Eastwood's merciless sensibility, gives the film its own unique quality.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1968

-Science fiction abruptly becomes respectable with Fox's Planet of the Apes and MGM's half-British 2001: A Space Odyssey

-Even the most cheerily fake corners of pop culture want in on the new world of edgy art cinemas, as The Monkees star in Bob Rafelson's psychedelic indie Head

-But plenty of people would rather pretend that nothing is changing, as Fox grimly craps out the bloated musical epic Star!

Elsewhere in world cinema in 1968

-Georgian-Soviet director Sergei Parajanov makes his best-known film, The Color of Pomegranates

-Sergio Leone directs the grandest of all Italian-made Westerns, Once Upon a Time in the West

-Amidst Europe-wide political protests, the Cannes Film Festival is canceled

It was an open admission by the establishment that American cinema had, over the course of 34 years of de facto censorship, been steadily losing ground in its ability to depict stories that reflected the content of real life and to express the full range of human experiences and thoughts. It triggered a sudden expansion of possibilities that lead to a flurry of studio-backed and independent filmmaking between 1969 and 1975 or so that bore witness to widespread creativity and experimentation that has only existed a few times in the history of American cinema.

This leaves '68 as something of a transitional year, when old-style Hollywood was still puttering to a close while what was not yet called the New Hollywood Cinema hadn't started to coalesce as any kind of clear movement. It's kind of an irresistible metaphor, if an appallingly shallow one, for a year that ranks among the most chaotic in modern history: the increasing fervor of the anti-war protests, along with high-profile political assassinations, the high water mark of the visibility of hippie culture, and the last screaming gasps of organised racism in the form of George Wallace's last presidential run, all served to put the United States in a state of near-madness that it hasn't experienced in any other single calendar year since the end of World War II. And the U.S. wasn't even particularly noteworthy for its social upheavals compared to the revolutionary activity sweeping through Europe at the same time.

It's all enough to make movies seem very silly and irrelevant, especially since the long lead time on film production means that nothing released in '68 could engage with that social chaos in its complet scope, or fully explore the new freedoms of post-Code Hollywood. But discussing movies is precisely what we're here to do, so however narrow and unhelpful a window it provides into the world at that time, let us turn now to Coogan's Bluff, a film that combines unabashed conservatism with ebullient liberalism and thus does the best job I could come up with of embodying all the tensions, both social and aesthetic, of that definitive year. It is, along with the same year's better-known Bullitt, a cop action movie that feels astonishingly ahead of its time: based on the urban grittiness of the mise en scène, the blanched feeling to the cinematography, and especially the Lalo Schifrin score (another trait the film shares with Bullitt), in the third year of that composer's prominence as a creator of funk-touched jazz, it would be easy to assume that the film was from the early '70s.

In fact, there's very little aesthetically to clearly differentiate it from 1971's Dirty Harry, the ur-action film of the 1970s. Particularly since it shares with Dirty Harry director Don Siegel and star Clint Eastwood (as well as co-writer Dean Riesner, whose work I gather to have largely consisted of following Eastwood's orders), making it something of a dry run for that later, better, and better-known celebration of fascism. They share a thematic wheelhouse: hardass cop who gets the job done runs afoul of bureaucracy and the weirdos of the counterculture. They look virtually identical: Coogan's Bluff was shot by Bud Thackeray, and Dirty Harry by Bruce Surtees, but both have that flat browned-over look that stamps so many movies as coming out in that era. Coogan's Bluff is a bit less tough than its successor: it's not nearly as violent, has less action overall (really, just a climactic chase sequence), and a considerably sunnier sense of humor, though the list of films that are funnier than Dirty Harry is awfully long.

It's altogether a wiry, tense little bundle of energy, a perfect example of Sigel's talent for creating lean, merciless action films and thrillers. It was the first film he and Eastwood made together, in a tremendously important professional relationship that resulted in five absolutely quintessential titles in both men's filmographies (or at least four plus the comic Western Two Mules for Sister Sara, the obvious "one of these things is not like the others" title among their collaborations), and cast a shadow over Eastwood's own directorial efforts from which he didn't fully emerge until at least the mid-'80s, if indeed he ever has.

The film finds Eastwood playing Coogan, an Arizona deputy sheriff tasked with heading to New York to bring back escaped killer James Ringerman (Don Stroud, when we eventually see him), currently in NYPD custody. Upon arriving on the East Coast, Coogan devotes all of his energy to leaving again as soon as possible, with his irritated attitude getting him nowhere with the stubborn Lt. McElroy (Lee J. Cobb), who acts with deliberate slowness in helping Coogan through the paper-pushing necessary to extradite Ringerman, currently recovering from a bad LSD trip in hospital under police watch. Eventually, Coogan's impatience causes him to cheat the system to get to Ringerman faster, but this has the unfortunate side effect of putting the fugitive in a perfect position to escape from Coogan, meaning that the Arizona lawman now has to dive right into the messiness of New York life in order to get his quarry back.

There's no better place to start with the film's every-which-way morality than with Coogan himself, a character who clearly fucks up in a way that the film never exonerates him for, and yet we're so clearly meant to identify with him and his befuddled anger at the wall of bureaucracy driving the New York police that it's also never the case that he's pointed out to be in the wrong at any moment. Part of that, undoubtedly, is the basic fact that Coogan was being played by Eastwood, right in the thick of his "hot new movie star" days - two years after The Good, the Bad and the Ugly sealed the deal on turning him into an icon, a performer who automatically reads as 'the good guy" regardless of whether or not the scrip surrounding him concurs. Even as the film treats his Southwestern badassery with a certain detached amusement at the corny incongruity of a taciturn cowboy-hero parading around in the 1960s, it also sides with him against the haughty New Yorkers so attached to their fast-paced city living that they call out that same corniness.

Similarly, the film's depiction of New York in the countercultural age splits a weird difference between trying its best to depict the energy and openness of that era, with the alarmed confusion of someone who will never be part of that world and doesn't want to. There's a sequence set in a club - I am not certain at all if it's the club, the house band, or both that are named Pigeon-Toed Orange Peel, but that name appears in giant neon with a theme song playing underneath scenes of stoners and drop-outs and radicals dancing around in brightly colored insanity. It is one of the great overwrought "what the fuck, New York?" scenes of the decade, depicting the nightmare that straitlaced Midwesterners have about Those People, far more than I suspect it depicts anything that ever actually existed. But even if the depiction is crazy paranoia, the tone is far more muted and sedate: Coogan seems entirely unruffled by what's going on around him, and the film that actively clings to his perspective has no choice but to follow suit. Instead of gawking at the freaks, the film simply depicts them, indulging in its ability to show drug use and nudity much as it indulges in the cruel efficiency of Coogan the law enforcer, edgy in a way that no American film released prior to 1967 would have been permitted.

The film's attempt to have its cake and eat it too could easily look like rank cynicism, except that I'm reasonable confident that it's a side effect of the film's actual function and purpose, which have nothing do with themes about The Way The World Is, as much fun as it is to read those themes into it (it is, anyway, far more rewarding and revealing to piece together society's self-analysis through films that aren't doing it on purpose, and thus can't be willfully picking and choosing what they represent). There's never a moment of Coogan's Bluff where it ever ceases to resemble a Don Siegel film, and Siegel as a director was driven by a desire to ruthlessly and efficiently tell thrilling stories with every possible piece of extraneous material carved away. He is as close as American cinema has produced to Ernest Hemingway: a superlatively masculine artist for whom blunt, unpoetic directness is privileged above all other things. The focus here is on Coogan and his process: everything that contributes to that is kept in and everything that gets in the way is jettisoned, leaving a freakishly slender, direct cop picture. There's an immediate clarity to the shots, composed and blocked and cut together not to imply secret depths or emotional currents, but to present the physical places of the movie with unblinking presence, and to watch the characters doing exactly what they have to do. It is not a film of inner lives: even Coogan's weirdly persistent womanising, maybe the most dated element of the film (I am totally unable to parse its sexual politics, I must confess), speaks less to his sexual appetites or his virility, than his pragmatism in manipulating people to help to his ends. This might be the sleekest Siegel film I have seen, which isn't all the same as calling it the best: frankly, its mechanical precision gets to be a little alienating, and even Dirty Harry feels like it has real people in a way that this film frequently doesn't. It's wry, persistent sense of humor is a godsend: without frequent touches of light irony, Coogan's Bluff could easily pivot into being genuinely unpleasant.

Instead, it's a satisfying police yarn with some really great, physically hefty location photography, and a fine star turn by Eastwood before he'd begun to really massage his persona into something more than a sardonic badass. I imagine it might have seemed more impressive in '68 than it does now: it's no-bullshit city thriller attitude was far rarer then, and many of the films in more or less the same mode in over the next few years are certainly more impressive on the level of characterisation and world-building. But Coogan's Bluff is a taut entertainment in its own right. And while it has neither the depth nor complexity that many of its descendants do, it came out early enough that the world it depicts feels totally different than any of them. It looks and acts like a '70s movie, but it is a '60s movie, and the tension that feeds, especially filtered through Siegel and Eastwood's merciless sensibility, gives the film its own unique quality.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1968

-Science fiction abruptly becomes respectable with Fox's Planet of the Apes and MGM's half-British 2001: A Space Odyssey

-Even the most cheerily fake corners of pop culture want in on the new world of edgy art cinemas, as The Monkees star in Bob Rafelson's psychedelic indie Head

-But plenty of people would rather pretend that nothing is changing, as Fox grimly craps out the bloated musical epic Star!

Elsewhere in world cinema in 1968

-Georgian-Soviet director Sergei Parajanov makes his best-known film, The Color of Pomegranates

-Sergio Leone directs the grandest of all Italian-made Westerns, Once Upon a Time in the West

-Amidst Europe-wide political protests, the Cannes Film Festival is canceled

Categories: action, clint eastwood, crime pictures, hollywood century