Life is beautiful

To get the grubby part out of the way first: Life Itself is a somewhat banal piece of documentary craftsmanship. A lot of talking heads, e-mails represented by onscreen text, old clips. It's something we've all see a billion times, and it is frankly disappointing that Steve James, the man who made the expansive epic of African-American teenage life Hoop Dreams and the exemplary social commentary boots-on-the-ground vérité piece The Interrupters would make something so gosh-darned safe, aesthetically speaking.

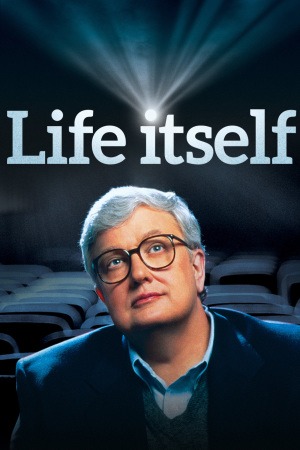

Now that's the nitpicky part, whereas the important part is that Life Itself doesn't really have any cause to be aesthetically complex or outrageously creative. It is a tribute to an individual man, as fully fleshed-out as any one depiction of any one human being might need to be. That man being Roger Ebert, the film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times and co-host of a succession of "dueling critics" TV shows with Gene Siskel over the course of more than two decades, and the inspiration for more current professional and amateur movie critics than anyone else who has ever lived. And of course, because movie reviews are written by movie reviewers, that makes it kind of hard for any of us - the present author happily discloses himself as having been intoxicated by Ebert's writing ability and obvious, overriding love of the art-form, long before I ever even dreamed of doing it myself - to take a genuinely objective view on what James has given us. It is a love letter that's incredibly difficult for most cinephiles to disagree with, and a deeply sweet, affecting balm on what remains, for a lot of people, a still-raw wound all this time after Ebert's death in April, 2013.

But a lack of objectivity is kind of the point of the thing. This is not about Steve James studying a famous man, but eulogising a person to whom he owed much (Siskel & Ebert basically created his career with their effusive love for Hoop Dreams), a friend he came to know well during the last few months of the critic's life, as he worked with James on creating the film that he eventually realised he wouldn't be alive to see completed. James's Ebert is personally warm, quick-witted even when his quips have to be translated through the electronic voice program Ebert relied in his last years, and a clear enthusiast for movies and for living. It's a view largely reflected by the wide range of interview subjects from his closest friends to other critics, not all of whom have had terribly kind things to say about Ebert's contributions to cinema studies. And even his friends are disinterested in whitewashing Ebert's crazed past, his peccadilloes, his occasional selfishness, and his irritable relationship with best frenemy Siskel, a professional rivalry that had some real nasty flickers on the edges, to judge from what we see (James includes footage of the two men bitching each other out while filming promos for their show; if Life Itself served absolutely no other function besides putting that footage out in the world, it would be worth every penny).

The small genius of Life Itself is that it is a film about a generous and open soul that is itself generous and open; eager to embrace Ebert for his fullness and messiness as a critic and a person, and thus reflecting the version of the man it depicts. It's structured to largely take place in the last months of Ebert's life, looking backwards to tell his story but always returning to the hospital where Ebert went through one health crisis after another with the support of his wife Chaz. The contrast between Ebert's late physical impairment and the ebullience of his younger days is striking, but James doesn't use it to beg for sympathy on his subject's behalf; instead, it's a way of throwing into sharp relief how Ebert had only deepened in his appreciation for living even as life became a chain of disgusting, obviously uncomfortable medical procedures and an increasingly circumscribed ability to move. There is never a moment when he complains, or bemoans his fate; the overall impression is of a man greatly at peace with his impending death, and anxious to find the pleasure and beauty in every day he had left.

It sounds trite in its uplifting, inspiring sentiment, but so fully based in the very specific details of who Ebert was and how he thought that it never even once comes over as a bit of pandering "let the cripple show us the way!" exploitation. Mostly, it's getting to learn a great deal about one person, and finding out that he was sensitive, prickly, loving, egocentric, and above all things an infectious communicator of ideas. Inasmuch as it's a hagiography - and I suppose it's awfully hard to claim otherwise - it's a hagiography of Ebert the person that James studied and observed, not a hagiography of Ebert the movie critic.

Of course it has its decent share of flaws, including some fuzzy generalisations about the non-Ebert state of criticism (Pauline Kael, by no means a favorite of mine, deserves better than she gets), and while I understand James's decision to have voice actor Stephen Stanton read excerpts from Ebert's blog and memoirs in an almost-but-not-quite perfect impression of the critic, it never quite managed to stop feeling ghoulish, for my tastes. And it is a pretty straightforward biopic-documentary; immensely likable but always more impressive on the level of content than craft - though that content, including surprisingly personable chats with directors legendary (Martin Scorsese) and obscure (Ava DuVernay), and the always delightful archival footage of Ebert getting into hissing matches with Siskel, is absolutely terrific stuff.

Anyway, James isn't trying to be clever or cunning, but simply to be honest; and he is wonderfully honest indeed. It is a warm film but too intimate not to include some uncomfortable moments, gross truths about the human body, and the occasional moment of bleak sorrow. And it fully lives up to the demand that the subject made in an e-mail to his last chronicler, in explaining why he wanted James to push on through the nastiness even though Chaz would object:

Now that's the nitpicky part, whereas the important part is that Life Itself doesn't really have any cause to be aesthetically complex or outrageously creative. It is a tribute to an individual man, as fully fleshed-out as any one depiction of any one human being might need to be. That man being Roger Ebert, the film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times and co-host of a succession of "dueling critics" TV shows with Gene Siskel over the course of more than two decades, and the inspiration for more current professional and amateur movie critics than anyone else who has ever lived. And of course, because movie reviews are written by movie reviewers, that makes it kind of hard for any of us - the present author happily discloses himself as having been intoxicated by Ebert's writing ability and obvious, overriding love of the art-form, long before I ever even dreamed of doing it myself - to take a genuinely objective view on what James has given us. It is a love letter that's incredibly difficult for most cinephiles to disagree with, and a deeply sweet, affecting balm on what remains, for a lot of people, a still-raw wound all this time after Ebert's death in April, 2013.

But a lack of objectivity is kind of the point of the thing. This is not about Steve James studying a famous man, but eulogising a person to whom he owed much (Siskel & Ebert basically created his career with their effusive love for Hoop Dreams), a friend he came to know well during the last few months of the critic's life, as he worked with James on creating the film that he eventually realised he wouldn't be alive to see completed. James's Ebert is personally warm, quick-witted even when his quips have to be translated through the electronic voice program Ebert relied in his last years, and a clear enthusiast for movies and for living. It's a view largely reflected by the wide range of interview subjects from his closest friends to other critics, not all of whom have had terribly kind things to say about Ebert's contributions to cinema studies. And even his friends are disinterested in whitewashing Ebert's crazed past, his peccadilloes, his occasional selfishness, and his irritable relationship with best frenemy Siskel, a professional rivalry that had some real nasty flickers on the edges, to judge from what we see (James includes footage of the two men bitching each other out while filming promos for their show; if Life Itself served absolutely no other function besides putting that footage out in the world, it would be worth every penny).

The small genius of Life Itself is that it is a film about a generous and open soul that is itself generous and open; eager to embrace Ebert for his fullness and messiness as a critic and a person, and thus reflecting the version of the man it depicts. It's structured to largely take place in the last months of Ebert's life, looking backwards to tell his story but always returning to the hospital where Ebert went through one health crisis after another with the support of his wife Chaz. The contrast between Ebert's late physical impairment and the ebullience of his younger days is striking, but James doesn't use it to beg for sympathy on his subject's behalf; instead, it's a way of throwing into sharp relief how Ebert had only deepened in his appreciation for living even as life became a chain of disgusting, obviously uncomfortable medical procedures and an increasingly circumscribed ability to move. There is never a moment when he complains, or bemoans his fate; the overall impression is of a man greatly at peace with his impending death, and anxious to find the pleasure and beauty in every day he had left.

It sounds trite in its uplifting, inspiring sentiment, but so fully based in the very specific details of who Ebert was and how he thought that it never even once comes over as a bit of pandering "let the cripple show us the way!" exploitation. Mostly, it's getting to learn a great deal about one person, and finding out that he was sensitive, prickly, loving, egocentric, and above all things an infectious communicator of ideas. Inasmuch as it's a hagiography - and I suppose it's awfully hard to claim otherwise - it's a hagiography of Ebert the person that James studied and observed, not a hagiography of Ebert the movie critic.

Of course it has its decent share of flaws, including some fuzzy generalisations about the non-Ebert state of criticism (Pauline Kael, by no means a favorite of mine, deserves better than she gets), and while I understand James's decision to have voice actor Stephen Stanton read excerpts from Ebert's blog and memoirs in an almost-but-not-quite perfect impression of the critic, it never quite managed to stop feeling ghoulish, for my tastes. And it is a pretty straightforward biopic-documentary; immensely likable but always more impressive on the level of content than craft - though that content, including surprisingly personable chats with directors legendary (Martin Scorsese) and obscure (Ava DuVernay), and the always delightful archival footage of Ebert getting into hissing matches with Siskel, is absolutely terrific stuff.

Anyway, James isn't trying to be clever or cunning, but simply to be honest; and he is wonderfully honest indeed. It is a warm film but too intimate not to include some uncomfortable moments, gross truths about the human body, and the occasional moment of bleak sorrow. And it fully lives up to the demand that the subject made in an e-mail to his last chronicler, in explaining why he wanted James to push on through the nastiness even though Chaz would object:

It would be a major lapse to have a documentary that doesn't contain the full reality.8/10

I wouldn't want to be associated. This is not only your film.

Cheers,

R

Categories: documentaries, the dread biopic, warm fuzzies