Hollywood Century, 1944: In which the effect of war on the folks back home is examined in perhaps more detail than is called for

"This is a story of the Unconquerable Fortress: the American Home...1943"

You know Mrs. Miniver, yes? Let's talk about it like you don't: Mrs. Miniver is a film about British Fortitude on the Home Front during The War. It strike a massive chord with wartime audiences, ending up the highest-grossing film of 1942, winning six Oscars when that was a huge number (it was the second-largest Oscar haul in history at the time), and generally staking a claim to the Zeitgeist in a way that few movies throughout the '40s ever did.

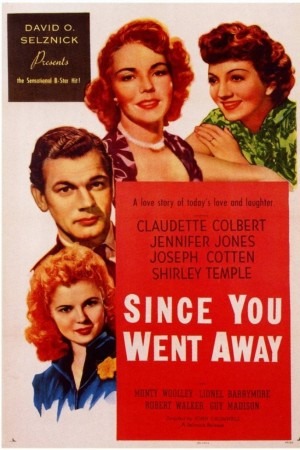

The reasoning must have seemed painfully obvious: if a film about Brits - an American-made film, but still - could make that big of a splash in the United States, surely a film about Americans would make an even bigger splash. And it so happened that the mind in which this painfully obvious thought manifested itself was that of superproducer David O. Selznick, who hadn't made a film since the massive one-two punch of Gone with the Wind and Rebecca in '39 and '40, and who was even before those films accustomed to making the most sprawling, high-cost, only-in-Hollywood spectacles that a single mogul could oversee. So when the American Miniver finally revealed itself, it was in the form of the mammoth Since You Went Away, a lugubrious Selznick megaproduction whose depiction of a year in the life of an American family nervously waiting on a father and husband gone off to war stretches out over nearly three hours. Most films, in the transition from novel to screen, are compelled to cut out details to fit; Since You Went Away, it's my understanding, was actually expanded from Margaret Buell Wilder's book, on account of there not being enough material for the grandiose homefront epic Selznick wanted.

Well, he got it alright: Since You Went Away makes an absolute monolith out of the tale of the Hiltons, whose life is interrupted when Tim Hilton, a man old enough not to have to go to war at all, reports for duty on January 12, 1943. This leaves his wife Anne (Claudette Colbert) nobly, statuesquey holding down the fort as their daughters - high school senior Jane (Jennifer Jones) and young teen Bridget (Shirley Temple) - try to wrap their heads around the new reality of everyday life. A lodger is taken in, Col. William Smollett (Monty Woolley), Tim and Anne's good friend Lt. Tony Willett (Joseph Cotten) comes around as often as he can to flirt with Anne, and Smollett's grandson Bill (Robert Walker) starts to take a more than friendly - and reciprocated - interest in Jane. On the finges, Anne's best frenemy Emily Hawkins (Agnes Moorehead) says snitty, catty things about the war, and housekeeper Fidelia (Hattie McDaniel, in a thankless role even by the standards of her career) is sassy and black.

It's a sprawling "watch as life is lived" tale with nothing that even resembles a narrative throughline, and that certainly doesn't help with the running time one little bit. But the bigger culprit in making sure that you feel every damn one of the film's 172 minutes - if you skip the five minutes of overture, intermission, and exit music - is its exhausting redundancy. By the end of the first hour, Since You Went Away has explored every idea it has about the stability and inner strength of the Ones Left Behind. By the end of the second hour, it's used up all the tricks it has available to stretch out those ideas a bit longer. That leaves nearly a full hour of meanspirited stubbornness, as the movie simply refuses to fucking end, pulling out ridiculous nonsense in an attempt to drag the thing out for no reason than so we can all compliment Selznick on the enormous size of his producer-cock. "Think we can't come up with any more random shit for Anne to do? Well, now she works at a shipyard, and she mentors a Polish-Jewish immigrant. LICK IT."

There's little doubt that the film's highlight is Colbert, whose confidence and anti-romanticism keep the film level and grounded, always bringing things back to the domestic sphere with intimacy and straightforward plainness. Whether it's deflecting, gently, Tony's overly eager advances or expressing private annoyance with Smollett in a wholly ungracious, feminine fashion, Colbert is smoothly, appealingly human at all turns, and she even manages to earn the film's bombastically mawkish finale. To the degree that Since You Went Away has anything to say about human beings, in 1943 or otherwise, it's because Colbert forces it to: her exhaustion and patience and always present but not always vocal patriotism are the exact embodiment of what people in America during the war might have been at the most sincere, not at their most idealised.

But man, the thing around her is a rattletrap mess. Cotten, faced with a character whose motivation never budges from "you want to have sex with a woman married to a man you adore, knowing full well that under no circumstances will she say yes", simply folds up after he snags a few easy laughs in the first hour; Temple, in one of her first more-or-less "grown-up" roles, plays things a bit too manic and eager for comfort. The less said about Jennifer Jones, the better; at least, I wish that were the case, but given the way that whole segments of the movie are conceded to her entirely - five years after the film opened, she'd be Mrs. David O. Selznick, and who knew when that began to grow - it's not possible. She gets a far more dynamic arc than Colbert ever does, and plenty of admiring scenes and frames, for back in '44, she was the New Thing, though a new thing who never exactly took off to the box office stratosphere as a real proper movie star. I will confess that I do not like her in anything, finding there to be something awfully insincere and faked about her emotions and physical bearing; she always strike me as someone terribly annoyed at having to be involved with movies, something she does not apparently regard as worthy of her dignity. This is not her worst performance: if nothing else, she's able to fire off a lot of innocent enthusiasm for Bill, all the more impressive since she and Walker, married at the start of production, separated and began divorce proceedings before it was complete. She disguises this complete, as Walker absolutely does not. Still, that gets us so far, and the rest of the way is all bright, cloying squeakiness and a frenzied attempt to be girlish.

Like Gone with the Wind before it, the film had a rotating cast of directors - John Cromwell ended up with the credit - which leaves it with little distinct personality other than Selznick's own. There are some graceful moments, including the lovely tracking shot that opens the film, a concise experiment in visual exposition, and some dramatic shots of injured soldiers, but in the main, the images are as snug and conventional as the family life Selznick wants to portray. This isn't a flaw, maybe: the Hilton home is cozy and well-appointed, simple and normal, and the visuals reflect that. But there's not much variety, and after three hours, that lack of variety starts to wear. Besides, the one-size-fits-all style means that the film tends to be awfully emotionally inert, with only Max Steiner's horribly insistent score, with its obvious musical riffs (here a military march, there a Christmas carol, and invention nowhere to be found), doing much to suggest that the events we see might have some emotion attached to them.

Colbert is too good, and the script (though bloated) too full of lovely details about small town American life in the '40s to reject it outright, but my God, is it wearisome. Above all things, the film yearns, aches, pleads to be thought of as a Serious, Deep, and Beautiful depiction of life, and Deserving of Respect, Admiration, and Awards. Basically, it's topically sensitive and dramatically stuffy Oscarbait: blunt proof of that particular style's long life ages before you might naturally think of it having made its dully prestigious presence known in the world.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1944

-Bing Crosby headlines the smash hit about singing Catholics, Going My Way

-Alfred Hitchcock makes the one-location wartime thriller Lifeboat

-Judy Garland introduces the melancholy holiday standard "Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas" in MGM's Meet Me in St. Louis, directed by Vincente Minnelli

Elsewhere in world cinema in 1944

-Sergei Eisenstein releases Ivan the Terrible, Part I, inaugurating the project that would consume the rest of his career

-Ingmar Bergman arrives on the scene in Sweden, writing the script for Alf Sjöberg's Torment

-Laurence Olivier directs and stars in the grandly theatrical Henry V, a masterpiece of Shakespearean cinema doubling as a wartime morale-booster