Blockbuster History: Disney plundering its animated canon

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: with Maleficent, Disney updates a great cartoon from their Silver Age with a dubious live-action update that feels like it exists solely to facilitate a great movie star playing a redo of one of the best villains in animation, a role she was clearly born for. This is not the first time that this exact situation has happened.

When Disney decided to make a live-action version of its 1961 animated classic One Hundred and One Dalmatians - it obviously being the case that simply not remaking it was too ridiculous and perverse a notion to even contemplate - one of the things that happened was that John Hughes was hired to write and produce. This was undoubtedly because of the onetime teen movie impresario's hand in birthing Beethoven, first of the 1990s wacky pet comedies, and it turned out to be a definitive choice. For the ultimate version of 101 Dalmatians, released at Thanksgiving in 1996, is every inch a Hughes film. Not because the dalmatians sit around and talk about life as high schoolers and discover that there's more to them than just being a doggy jock, a doggy geek, a doggy princess, and so on, though that film would have been so much better that I weep to think of it. Rather, 101 Dalmatians feels like the culmination of Hughes in his "I don't care, give me fucking money" phase; it plays like a crude, clumsy welding of Beethoven (nonspeaking animals doing wacky things) and Home Alone (a protracted third act of alarmingly violent slapstick) stuffed into the narrative framework of the 35-year-old film, with considerable stretches of dialogue taken from the same source.

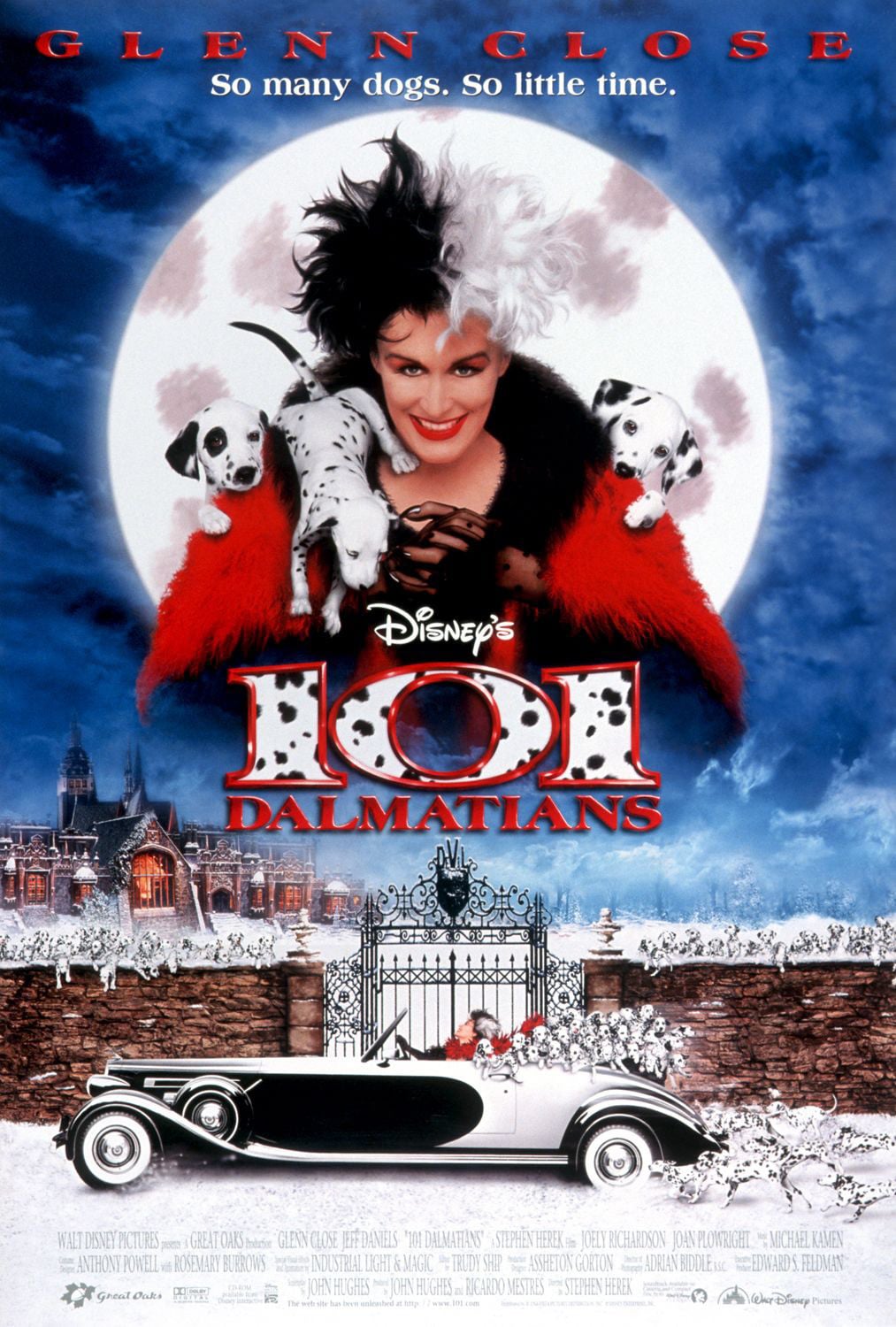

The results of that Frankensteinian tinkering with scattered body parts are not pretty, though we must pay the film this much respect: it gave the world Glenn Close playing iconic crazy woman villain Cruella De Vil, and that is something all fans of talented actresses uncorking it and having a bit of hammy, campy fun must acknowledge to be an ultimate good in the universe. Even if Close is a bit broader and therefore more fun in the much more deranged and therefore more interesting 2000 sequel 102 Dalmatians. We needed to go through this movie to get to that one, and so it still earns our thanks, however fatigued and sad those thanks might be.

In all ways, the film more closely resembles Disney's original film than the Dodie Smith book from which it claims descent. In London, there are two dogs, Pongo and Perdita, and they are respectively owned by an unemployed American video game designer named Roger (Jeff Daniels) and an English hold tight now, a video game designer? This is the way you sexify up the story of 101 Dalmatians for a 1990s audience, John Hughes? And boy, does the video game he's designing ever look unplayable - it's basically what you'd get if you asked, say, a team of Disney animators to whip up some "game footage" based on the character models from the animated Dalmatians, and don't particularly care if it resembles in any degree the kind of games that actually got played in 1996, or at any point before or after.

Perdita, then is owned by Anita (Joely Richardson), a fashion designer who works at House of De Vil, where she is a favorite of namesake, owner, and guru Cruella De Vil, who notices one day that Anita has been noodling around with a line based on irregular spots, inspired by her photo of Perdita. And this puts a bee in Cruella's bonnet that will not fly away. But it takes a while before she's able to do anything with this insight. First, Pongo and Perdita spot each other in a park, and then contrive to get Roger and Anita all mixed up and fallen in love; before you can say "quickie wedding" their houses are combined and Perdita is heavy with child. Children. 15 children, in fact, a robust litter of dalmatian pups that Cruella offers to buy on the very day of their birth. When Roger finds this all distasteful and suspicious, the fashion magnate opts for plan B: have a pair of idiot thieves, Jasper (Hugh Laurie) and Horace (Mark Williams), kidnap the puppies and take them into the country with 84 others, exactly the number Cruella requires to fashion for herself a dalmatian-skin outfit. The humans are distraught, but the dogs, communicating through an impressive network of barks, are able to track their family out of the city, where they and several other species of animal wreak their wide-rainging revenge on Cruella and her henchmen, including the angry mute furrier Mr. Skinner (John Shrapnel).

None of this is any damn good, though the film does itself no favors by ending on its worst material, the lengthy slapstick booby traps sequence in which the dogs, along with farm animals and a pair of teamwork-oriented raccoons, perpetrate all manner of indignities upon the human villains. The adult viewer cannot help their mind from wandering during all this, to ponder what possibly could have been going through the mind of five-time Academy Award nominee and three-time Tony winner Glenn Close as she read the descriptions in the screenplay of "Cruella drops into a barrel of molasses" and "Cruella slides backwards at high speed through a pool of pig shit", or what director Stephen Herek* might have said to her to get her prepared for the scene where a pig is catapulted onto her chest and she must feebly kick and scream for help.

That being said, Close is - by lots - the best thing happening in the entire movie. Recognising what kind of movie she was in and what kind of character she was playing, she turned off whatever filter actors have that makes them look for character truth or internal credibility, and went from 0 to psycho in one scene flat. It's a glorious thing to behold, when someone with Close's talents and authoritative presence just cuts loose and goes for it: there are manical giggles galore, and every line she speaks is in a relentlessly cheery scream, full of bizarre private amusement. There aren't many movie villains who take actual pleasure in being evil, for the sake of it; Close's Cruella belongs to that company, and while it's not nearly enough to elevate the movie itself, at least we get some one-of-a-kind live action cartooning to enjoy. Even without borrowing any affection the audience might have for the animated original, Close creates an iconic, comically menacing character that lingers in the memory long after the bland nonsense of the film has faded.

And boy, does it ever fade. 101 Dalmatians is utterly devoid of anything that has a personality at all, let alone anything genuinely appealing. Having made the (probably appropriate) choice not to have the animals speak, the film immediately hits the wall that both Disney's film and Smith's book take Pongo and Perdita as their protagonists, which now becomes virtually impossible. Not that stories with non-speaking animals as protagonists can never work, but when you hire John Hughes and Stephen Herek to make a family movie, you don't expect, don't want, and don't get Au hasard Balthazar. So the story no longer centers on the dogs; but it doesn't really center on anyone else - Cruella would be the obvious choice, but Disney wasn't interested in making movies about bad guys just yet. Roger and Anita are too bland - and Daniels's performance certainly isn't looking to counteract that impression - and that leaves basically nobody else. So the film descends into a free-floating collection of scenes that barely stitch together and have no particular visual flair: the costumes are the most interesting thing to look at in a movie that is content to have the actors stand in front of the camera delivering lines, while a mix of well-trained animals and animatronic critters (and sometimes, vengefully bad CGI ones) enact insipid jokey behaviors designed to appeal only to young and extremely unsophisticated children.

It's lowest-common-denominator kiddie filmmaking, basically, propped up by a weirdly committed and nasty-minded performance by the villain. Not the first time it ever happened, but it's especially irritating in this case: what Close is up to is so damn great that I'm almost bizarrely tempted to try and recommend the film, even though everything - everything - around her is at the most dire, shitty levels that 1990s family entertainment could manage to operate.

*Who we just saw last week, when he was helming Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure, a coincidence of which I was unaware when I assembled this summer's schedule.

When Disney decided to make a live-action version of its 1961 animated classic One Hundred and One Dalmatians - it obviously being the case that simply not remaking it was too ridiculous and perverse a notion to even contemplate - one of the things that happened was that John Hughes was hired to write and produce. This was undoubtedly because of the onetime teen movie impresario's hand in birthing Beethoven, first of the 1990s wacky pet comedies, and it turned out to be a definitive choice. For the ultimate version of 101 Dalmatians, released at Thanksgiving in 1996, is every inch a Hughes film. Not because the dalmatians sit around and talk about life as high schoolers and discover that there's more to them than just being a doggy jock, a doggy geek, a doggy princess, and so on, though that film would have been so much better that I weep to think of it. Rather, 101 Dalmatians feels like the culmination of Hughes in his "I don't care, give me fucking money" phase; it plays like a crude, clumsy welding of Beethoven (nonspeaking animals doing wacky things) and Home Alone (a protracted third act of alarmingly violent slapstick) stuffed into the narrative framework of the 35-year-old film, with considerable stretches of dialogue taken from the same source.

The results of that Frankensteinian tinkering with scattered body parts are not pretty, though we must pay the film this much respect: it gave the world Glenn Close playing iconic crazy woman villain Cruella De Vil, and that is something all fans of talented actresses uncorking it and having a bit of hammy, campy fun must acknowledge to be an ultimate good in the universe. Even if Close is a bit broader and therefore more fun in the much more deranged and therefore more interesting 2000 sequel 102 Dalmatians. We needed to go through this movie to get to that one, and so it still earns our thanks, however fatigued and sad those thanks might be.

In all ways, the film more closely resembles Disney's original film than the Dodie Smith book from which it claims descent. In London, there are two dogs, Pongo and Perdita, and they are respectively owned by an unemployed American video game designer named Roger (Jeff Daniels) and an English hold tight now, a video game designer? This is the way you sexify up the story of 101 Dalmatians for a 1990s audience, John Hughes? And boy, does the video game he's designing ever look unplayable - it's basically what you'd get if you asked, say, a team of Disney animators to whip up some "game footage" based on the character models from the animated Dalmatians, and don't particularly care if it resembles in any degree the kind of games that actually got played in 1996, or at any point before or after.

Perdita, then is owned by Anita (Joely Richardson), a fashion designer who works at House of De Vil, where she is a favorite of namesake, owner, and guru Cruella De Vil, who notices one day that Anita has been noodling around with a line based on irregular spots, inspired by her photo of Perdita. And this puts a bee in Cruella's bonnet that will not fly away. But it takes a while before she's able to do anything with this insight. First, Pongo and Perdita spot each other in a park, and then contrive to get Roger and Anita all mixed up and fallen in love; before you can say "quickie wedding" their houses are combined and Perdita is heavy with child. Children. 15 children, in fact, a robust litter of dalmatian pups that Cruella offers to buy on the very day of their birth. When Roger finds this all distasteful and suspicious, the fashion magnate opts for plan B: have a pair of idiot thieves, Jasper (Hugh Laurie) and Horace (Mark Williams), kidnap the puppies and take them into the country with 84 others, exactly the number Cruella requires to fashion for herself a dalmatian-skin outfit. The humans are distraught, but the dogs, communicating through an impressive network of barks, are able to track their family out of the city, where they and several other species of animal wreak their wide-rainging revenge on Cruella and her henchmen, including the angry mute furrier Mr. Skinner (John Shrapnel).

None of this is any damn good, though the film does itself no favors by ending on its worst material, the lengthy slapstick booby traps sequence in which the dogs, along with farm animals and a pair of teamwork-oriented raccoons, perpetrate all manner of indignities upon the human villains. The adult viewer cannot help their mind from wandering during all this, to ponder what possibly could have been going through the mind of five-time Academy Award nominee and three-time Tony winner Glenn Close as she read the descriptions in the screenplay of "Cruella drops into a barrel of molasses" and "Cruella slides backwards at high speed through a pool of pig shit", or what director Stephen Herek* might have said to her to get her prepared for the scene where a pig is catapulted onto her chest and she must feebly kick and scream for help.

That being said, Close is - by lots - the best thing happening in the entire movie. Recognising what kind of movie she was in and what kind of character she was playing, she turned off whatever filter actors have that makes them look for character truth or internal credibility, and went from 0 to psycho in one scene flat. It's a glorious thing to behold, when someone with Close's talents and authoritative presence just cuts loose and goes for it: there are manical giggles galore, and every line she speaks is in a relentlessly cheery scream, full of bizarre private amusement. There aren't many movie villains who take actual pleasure in being evil, for the sake of it; Close's Cruella belongs to that company, and while it's not nearly enough to elevate the movie itself, at least we get some one-of-a-kind live action cartooning to enjoy. Even without borrowing any affection the audience might have for the animated original, Close creates an iconic, comically menacing character that lingers in the memory long after the bland nonsense of the film has faded.

And boy, does it ever fade. 101 Dalmatians is utterly devoid of anything that has a personality at all, let alone anything genuinely appealing. Having made the (probably appropriate) choice not to have the animals speak, the film immediately hits the wall that both Disney's film and Smith's book take Pongo and Perdita as their protagonists, which now becomes virtually impossible. Not that stories with non-speaking animals as protagonists can never work, but when you hire John Hughes and Stephen Herek to make a family movie, you don't expect, don't want, and don't get Au hasard Balthazar. So the story no longer centers on the dogs; but it doesn't really center on anyone else - Cruella would be the obvious choice, but Disney wasn't interested in making movies about bad guys just yet. Roger and Anita are too bland - and Daniels's performance certainly isn't looking to counteract that impression - and that leaves basically nobody else. So the film descends into a free-floating collection of scenes that barely stitch together and have no particular visual flair: the costumes are the most interesting thing to look at in a movie that is content to have the actors stand in front of the camera delivering lines, while a mix of well-trained animals and animatronic critters (and sometimes, vengefully bad CGI ones) enact insipid jokey behaviors designed to appeal only to young and extremely unsophisticated children.

It's lowest-common-denominator kiddie filmmaking, basically, propped up by a weirdly committed and nasty-minded performance by the villain. Not the first time it ever happened, but it's especially irritating in this case: what Close is up to is so damn great that I'm almost bizarrely tempted to try and recommend the film, even though everything - everything - around her is at the most dire, shitty levels that 1990s family entertainment could manage to operate.

*Who we just saw last week, when he was helming Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure, a coincidence of which I was unaware when I assembled this summer's schedule.