Blockbuster History: Your friendly neighborhood spider

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: The Amazing Spider-Man 2 is, like, the eightieth frigging superhero movie to come out since I first started this series. One must stretch a point at times, and I feel like stretching it as far as "story about a well-spoken arachnid or arachnid-adjacent character who does good deeds" was entirely fair game.

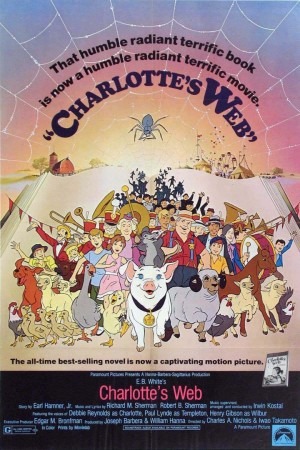

The first thing to point out is that E.B. White's 1952 children's book Charlotte's Web is unutterably perfect, and even a very bad cinematic adaptation, assuming it kept the basic shape (and, especially, the ending) intact, couldn't help but capture some of the impact that has made it such a reliable tear-jerker for so many generations of young readers in America (full disclosure: I was among those generations, and I have it on reliable authority that Charlotte's Web was the first properly book-length book that I ever read). The second thing to point out is that, pace White, whose opinion on the matter should count for at least something, the 1973 film of Charlotte's Web animated by Hanna-Barbera and released by Paramount is certainly not a very bad adaptation. Not, anyway, on the level of scripting. Like P.L. Travers before him, White objected to the presence of bouncy, "jolly" songs by Robert B. and Richard M. Sherman getting all in the way of his gentle emotional landscape, and I can see, from a conceptual standpoint, what he's going on about. But even sub-par Sherman songs (and God bless the movie and all who have fond memories of it, but these are decidedly not Mary Poppins-level tunes) are still catchy, lively, pleasant things to listen to, and I think that White was perhaps too close to the situation to appreciate how much of the mordant, autumnal emotions of his book's late chapters emerged in the film whole and intact.

Charlotte's Web, for those grossly deprived of an appropriate childhood, is a beautiful fable about death. That's probably a hard way of putting it. However, it opens with the specter of death hanging over a little community in Rural Americana, with a runt piglet being selected for the ax by sensible farmer John Arable (John Stephenson), when his tween daughter Fern (Pamelyn Ferdin) has a royal freak-out over the hideous, arbitrary world in which a small innocent thing can be killed just to get it out of the way. Despite this being a weird, disproportionate response for a girl who has presumably lived her entire life around farm animals, Fern gets her way, kind of, when her father decides to let her raise the pig and see what happens. What happens is that he becomes healthy and fat, enough so that he's sold to Fern's uncle Homer Zuckerman (Bob Holt), and it is here that the action shifts delicately over to an animal POV, with the Zuckerman farm animals all speaking a common language; it is thanks to the encouragement of a kindly goose (Agnes Moorehead) that the piglet, Wilbur (Henry Gibson), comes out of his shell; but it is an even more kindly barn spider, Charlotte A. Cavatica (Debbie Reynolds), who becomes his truest friend.

Death, however, is not done with Charlotte's Web: there are near-constant reminders of Wilbur's ultimate fate, and the clever, language-loving Charlotte decides to do something about it. What she does is entirely unbelievable on any level other than that of fable (by which I mean, even in the talking animal universe logic, the human response to her actions is pretty contrived), but Charlotte's Web, in any medium, doesn't claim to be more than a fable. Anyway, death is still not done with the story, and it finally arrives in an ending that absolutely fucking ruined me as a kid, both in print and onscreen, and I presume has fucking ruined many a child besides me. And it still has a unique ability to prod at the heart of all but the morbidly unsentimental, with its frank but tender approach to presenting the blunt fact that all of us will lose people we care about deeply in life and that's sad but it's also okay, because it's part of what happens in life; all this told in a simple, child-friendly vernacular.

The only way to completely ruin that ending would be by removing it altogether, which would be awfully hard to even imagine happening. There are also, however, ways of making that ending more or less potent, and here we get into things like casting and, yes, jolly Sherman brothers songs. And while the Hanna-Barbera Charlotte's Web is a fine and worthy telling of this story, it's certainly not the best one imaginable. There are the things that work outrageously well: Reynolds's kind, authoritative, and wholly unsentimental vocal performance leaps to mind as the single element that keeps the film most firmly anchored in a low-key, honest place. I am also fond, fonder than I can intellectual defend, of Paul Lynde's yawningly selfish performance of the scavenger rat Templeton. And the song "Deep in the Dark/Charlotte's Web", the easy highlight of the music, is an eery, soaring and sorrowful waltz that is beautiful while prefiguring the emotional wringer to come.

But then there's the bouncy nonsense of the more energetic "fun" songs, like the idiotic patter number "I Can Talk!". And Gibson's performance as Wilbur is a bit bizarre altogether, frankly; it's hard to imagine whose mental process consists of thinking that actor, of all actors, was the right fit for a callow juvenile pig, but there he is anyway. Giving a strange, meandering performance full of sweaty desperation and whining and a peculiar, alienating tendency to stick in the most extreme register of whatever emotion the script calls for in agiven moment.

The biggest liability by far, though, is the simple fact that Charlotte's Web was made by Hanna-Barbera. With due apologies to all the Yogi and Scooby-Doo fans out there, but I really wonder if that might have been the most hopeless significant American animation studio of its era; and yes, Filmation was Hanna-Barbera's near contemporary, so it's definitely a snug race to the bottom. The greater point is, the studio was not terribly well-equipped to deal with anything complicated or costly, and Charlotte's Web is poorly-animated and ill-designed. Especially as concerns the human characters: the studio's stock of model types apparently extends to about six females and three males, all of whom have that slack-jawed amazed look typical of Hanna-Barbera heroes, and whose actions are a debilitating mixture of limited movement (gotta save up on labor where you can), and exaggerated, flailing gestures.

The animals are at least marginally better, and Charlotte herself is actually quite lovely, budgetary limitations taken into account; she looks mostly like a spider, without any softening elements to her design (as exactly fits her character), and the gestures she makes with her eight legs are fluid and full of personality. But that's the absolute high water mark, and there's plenty of fairly dodgy work: the overacting done in animating Templeton, who is much too "big" at inappropriate moments, or Wilbur's tendency towards stiff facial poses. To say nothing of how hideously his color drifts throughout the film, from pink to a pale, necrotic white, back and forth.

It's a cartoon, basically, not an "animated film"; and that might not be a problem, but it's a cheap, limited, ugly cartoon. This is a far greater liability than any tendency towards making it a more friendly, straightforward story than the original novel; it leaves several of the characters feeling unlikable or ridiculous before they ever open their mouths. One cannot and should not expect the quality of even low-grade '70s Disney animation from every movie that comes along, but the gulf between the emotional flexibility of the story in Charlotte's Web and the stiffness of movement and rigid angles and poses of the visuals is a profound gulf. Again, it's really pretty much impossible to make this material fail on a significant, primal level, but this film lacks much grace or sensitivity as a work of animation (the coloring of the backgrounds is frequently very lovely), and its successes, though they are real and undeniable, are arrived at through something of a cheat, when all is said and done.

The first thing to point out is that E.B. White's 1952 children's book Charlotte's Web is unutterably perfect, and even a very bad cinematic adaptation, assuming it kept the basic shape (and, especially, the ending) intact, couldn't help but capture some of the impact that has made it such a reliable tear-jerker for so many generations of young readers in America (full disclosure: I was among those generations, and I have it on reliable authority that Charlotte's Web was the first properly book-length book that I ever read). The second thing to point out is that, pace White, whose opinion on the matter should count for at least something, the 1973 film of Charlotte's Web animated by Hanna-Barbera and released by Paramount is certainly not a very bad adaptation. Not, anyway, on the level of scripting. Like P.L. Travers before him, White objected to the presence of bouncy, "jolly" songs by Robert B. and Richard M. Sherman getting all in the way of his gentle emotional landscape, and I can see, from a conceptual standpoint, what he's going on about. But even sub-par Sherman songs (and God bless the movie and all who have fond memories of it, but these are decidedly not Mary Poppins-level tunes) are still catchy, lively, pleasant things to listen to, and I think that White was perhaps too close to the situation to appreciate how much of the mordant, autumnal emotions of his book's late chapters emerged in the film whole and intact.

Charlotte's Web, for those grossly deprived of an appropriate childhood, is a beautiful fable about death. That's probably a hard way of putting it. However, it opens with the specter of death hanging over a little community in Rural Americana, with a runt piglet being selected for the ax by sensible farmer John Arable (John Stephenson), when his tween daughter Fern (Pamelyn Ferdin) has a royal freak-out over the hideous, arbitrary world in which a small innocent thing can be killed just to get it out of the way. Despite this being a weird, disproportionate response for a girl who has presumably lived her entire life around farm animals, Fern gets her way, kind of, when her father decides to let her raise the pig and see what happens. What happens is that he becomes healthy and fat, enough so that he's sold to Fern's uncle Homer Zuckerman (Bob Holt), and it is here that the action shifts delicately over to an animal POV, with the Zuckerman farm animals all speaking a common language; it is thanks to the encouragement of a kindly goose (Agnes Moorehead) that the piglet, Wilbur (Henry Gibson), comes out of his shell; but it is an even more kindly barn spider, Charlotte A. Cavatica (Debbie Reynolds), who becomes his truest friend.

Death, however, is not done with Charlotte's Web: there are near-constant reminders of Wilbur's ultimate fate, and the clever, language-loving Charlotte decides to do something about it. What she does is entirely unbelievable on any level other than that of fable (by which I mean, even in the talking animal universe logic, the human response to her actions is pretty contrived), but Charlotte's Web, in any medium, doesn't claim to be more than a fable. Anyway, death is still not done with the story, and it finally arrives in an ending that absolutely fucking ruined me as a kid, both in print and onscreen, and I presume has fucking ruined many a child besides me. And it still has a unique ability to prod at the heart of all but the morbidly unsentimental, with its frank but tender approach to presenting the blunt fact that all of us will lose people we care about deeply in life and that's sad but it's also okay, because it's part of what happens in life; all this told in a simple, child-friendly vernacular.

The only way to completely ruin that ending would be by removing it altogether, which would be awfully hard to even imagine happening. There are also, however, ways of making that ending more or less potent, and here we get into things like casting and, yes, jolly Sherman brothers songs. And while the Hanna-Barbera Charlotte's Web is a fine and worthy telling of this story, it's certainly not the best one imaginable. There are the things that work outrageously well: Reynolds's kind, authoritative, and wholly unsentimental vocal performance leaps to mind as the single element that keeps the film most firmly anchored in a low-key, honest place. I am also fond, fonder than I can intellectual defend, of Paul Lynde's yawningly selfish performance of the scavenger rat Templeton. And the song "Deep in the Dark/Charlotte's Web", the easy highlight of the music, is an eery, soaring and sorrowful waltz that is beautiful while prefiguring the emotional wringer to come.

But then there's the bouncy nonsense of the more energetic "fun" songs, like the idiotic patter number "I Can Talk!". And Gibson's performance as Wilbur is a bit bizarre altogether, frankly; it's hard to imagine whose mental process consists of thinking that actor, of all actors, was the right fit for a callow juvenile pig, but there he is anyway. Giving a strange, meandering performance full of sweaty desperation and whining and a peculiar, alienating tendency to stick in the most extreme register of whatever emotion the script calls for in agiven moment.

The biggest liability by far, though, is the simple fact that Charlotte's Web was made by Hanna-Barbera. With due apologies to all the Yogi and Scooby-Doo fans out there, but I really wonder if that might have been the most hopeless significant American animation studio of its era; and yes, Filmation was Hanna-Barbera's near contemporary, so it's definitely a snug race to the bottom. The greater point is, the studio was not terribly well-equipped to deal with anything complicated or costly, and Charlotte's Web is poorly-animated and ill-designed. Especially as concerns the human characters: the studio's stock of model types apparently extends to about six females and three males, all of whom have that slack-jawed amazed look typical of Hanna-Barbera heroes, and whose actions are a debilitating mixture of limited movement (gotta save up on labor where you can), and exaggerated, flailing gestures.

The animals are at least marginally better, and Charlotte herself is actually quite lovely, budgetary limitations taken into account; she looks mostly like a spider, without any softening elements to her design (as exactly fits her character), and the gestures she makes with her eight legs are fluid and full of personality. But that's the absolute high water mark, and there's plenty of fairly dodgy work: the overacting done in animating Templeton, who is much too "big" at inappropriate moments, or Wilbur's tendency towards stiff facial poses. To say nothing of how hideously his color drifts throughout the film, from pink to a pale, necrotic white, back and forth.

It's a cartoon, basically, not an "animated film"; and that might not be a problem, but it's a cheap, limited, ugly cartoon. This is a far greater liability than any tendency towards making it a more friendly, straightforward story than the original novel; it leaves several of the characters feeling unlikable or ridiculous before they ever open their mouths. One cannot and should not expect the quality of even low-grade '70s Disney animation from every movie that comes along, but the gulf between the emotional flexibility of the story in Charlotte's Web and the stiffness of movement and rigid angles and poses of the visuals is a profound gulf. Again, it's really pretty much impossible to make this material fail on a significant, primal level, but this film lacks much grace or sensitivity as a work of animation (the coloring of the backgrounds is frequently very lovely), and its successes, though they are real and undeniable, are arrived at through something of a cheat, when all is said and done.