Hollywood Century, 1919: In which the inmates take over the asylum

The history of the American film industry from its formation into the 1950s is inextricably tied in with the history of trade unions and contracts. Here in the 21st Century, filmmaking on both sides of the camera is typically described in terms of artistry and what the actors, writers, directors, composers, cinematographers, sound designers et alia are trying to "say". For a very long time, though, filmmaking was a job, much like being an accountant, janitor, or mechanic. More glamorous, of course, in that involved being famous and (within limits) wealthy. But a job that took place week in and week out, with really terrible hours most of the time. Films were made almost according to the mentality of an assembly line at one point, even the ones that we now regard as great masterpieces; and this was especially so in the silent era, when it was possible to crank out an entire feature film from script to screen in just a few weeks.

For much of the Golden Age of the Hollywood studio system, the contract players in thrall to the executives devoted much of their time to finding ways to exert some kind of independence over what projects they would make and how they would be presented. Of the many individual attempts to break out in some little way from the seemingly immovable strictures of the big studios, perhaps no effort was so bold, or so far-reaching in its effects, as the formation of United Artists in 1919. The artists who were so uniting were four of the biggest names in American film at that time: superstar Mary Pickford, the most bankable human being in the world; her lover, the comedy-adventure star Douglas Fairbanks; D.W. Griffith, possibly the only director at that time who was his own brand name; and Charles Chaplin, multi-hyphenate talent and the only person in the movies who could challenge Pickford's fame and financial success. The idea was to create an independent production and distribution company that would allow these four mega-celebrities to work on their own terms, and while the experiment in its pure form didn't live very long (Griffith abandoned ship in 1924, while Fairbanks and Pickford saw their careers implode in the sound era, and Chaplin quickly became the sort of methodical, fussy artist who took years in between projects to get them right), the idea of an independent studio has never entirely died off since then, and United Artists itself continues to struggle along, though it exists at this time mostly as a shell company for creating James Bond pictures.

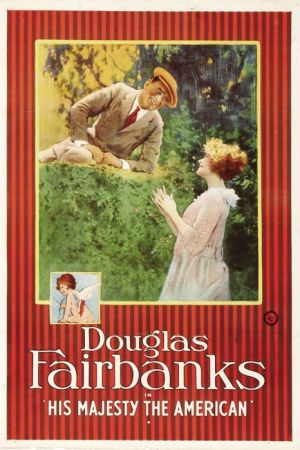

The first film released by United Artists, in the latter half of 1919, was the Fairbanks vehicle His Majesty the American. Then as now, Hollywood likes a sure thing more than a genuine gamble, especially if the sure thing can be made to look like a risk, and accordingly, UA aimed to get things started on a safe foot by releasing the kind of film that had been a hit in the past. At that time, Fairbanks was celebrated for his bubbly comedies set in milieus that gave him amble room to showcase his estimable skills as a physical performer, as much an acrobat as an actor. Those who know Fairbanks mostly as the sword-wielding star of costume dramas - which is just about everybody at this point, I suppose - would certainly be staggered by His Majesty the American, which does eventually become a quick-cutting adventure film of the sort he'd become even more famous for in the decade to follow, but only after spending plenty of time as a startling hybrid of political thriller in a Ruritanian principality, fish-out-of-water comedy, boys' own adventure, romantic comedy, and showcase for Fairbanks's skill divorced from narrative or genre. Hell, you don't even need to drag the star's persona into it: to modern eyes, the feverish assemblage of tones and narrative threads would be peculiar regardless of who was headlining the project. But as much as anything, that merely showcases what a freewheeling sense of the rules that still pertained as the '10s gave way to the '20s.

On the other hand, His Majesty the American is perhaps the first film I have turned to in this Hollywood Century project that largely resembles the kind of filmmaking that we're used to all these long decades later. The shots used are still considerably wider than anything in modern cinema: the proscenium-style compositions that define the middle silent era had a few more years of life in them. But the way those shots are broken up into inserts and close-ups, while a bit stiff at times, feels downright radical compared to movies made just one or two years earlier (something must have been in the water: Griffith's Broken Blossoms, typically agreed as having the first totally modern insert shots in American cinema, was UA's very next release). It is perhaps for this reason that the blithe mixture of genres and plots in the movie stands out so bluntly: the film has enough of a contemporary flow that it feels like it ought to behave like a contemporary film in other ways.

All that's a lot of verbiage to throw at a pleasant slip of a thing that isn't really very distinctive in any way you could name. It is, first and above all, a Fairbanks picture, meaning that most of what happens is at some level a contrivance designed to put Fairbanks in positions to show off. In this case, he plays Bill Brooks, a well-to-do New Yorker who has no idea where he came from or who his parents are, but somebody in his past is keeping an eye on him and throwing enough cash at him that he has no real worries in life and is able to pursue his passion to have adventures as an amateur fireman and policeman. We see each of these in setpieces staged with quite a lot of vigor and kinetic energy by writer-director Joseph Henabery (his fourth consecutive Fairbanks picture, near the start of a career that would include dozens and dozens of movies into the late '40s), with the burning tenement building that opens the film a particular standout of effects work and action choreography, setpieces that moreover make not the smallest effort to work themselves into the plot of the rest of the film, and are clearly just there as spectacle for spectacle's sake (talk about feeling modern). Eventually, the story rather arbitrarily packs Bill off to Mexico, to seek out ever more exciting adventures, and that's where he's contacted by representatives of the government of Alaine, a small kingdom in the European Alps currently experiencing some tension over the succession, with King Philippe (Sam Sothern) trying to democritise the country as Grand Duke Sarzeau (Frank Campeau) schemes none too subtly to destablise the king's position. Bill quickly ends up head-over-heels in dynastic intrigue, while also crossing paths with the lovely countess Felice (Marjorie Daw), proving to be the hero of the Alaine people in multiple ways involving greater and smaller demonstrations of swashbuckling and daring.

It's all a bit foggy in expression, though how much of that is the film and how much the heavily beat-up print that I was able to watch it in is up for debate. What's always clear, though, is that the film is first and foremost about Fairbanks, and in that regard it's largely, though not uniformly successful. There's the not-insignificant matter of the frequent cutaways in the first half or so of the film, before Bill arrives in Alaine, where the film spends minutes at a time dramatising the minutiae of politics in a made-up country with a zealous care that could only appeal to a filmgoing population still high on its love affair with Anthony Hope's 1894 novel The Prisoner of Zenda (which had been filmed twice in the 1910s). These scenes deaden a film that wages everything on being so fast and fizzy that we don't stop to notice the threadbare characters or muddy story, and it takes an awfully long time for the film to find its rhythm.

Once it does, it becomes a lot easier to notice the even bigger and more serious problem, one that maybe speaks to the changing nature of tastes over the years and maybe simply my own: Douglas Fairbanks isn't a terribly good comedian. Obviously, audiences in the '10s who made him a superstar on similar hybrids of comedy and adventure would disagree with me on that point, and I do not think it has anything to do with him. The problem is, simply, that he doesn't have a funny face. Look at the great comics of the same era whose work has remained more or less popular: Chaplin had his fussy, twitchy expressions and his absurd greasepaint hair; Buster Keaton his long face and unfazed, modestly unsettled expressions; Harold Lloyd's rubbery mouth and bright, open eyes; Fatty Arbuckle's round pie face with its tight little smile. Fairbanks, not yet boasting his matinee idol mustache, looks emphatically normal, with a bit prominent of a forehead and a slightly wider face than ordinary; he looks like the most handsome man in the real estate office. He certainly doesn't look like someone who should do the face-pulling and wacky activity he's called upon to do, and in such a visual medium, not looking funny is awfully close to not being funny.

Still and all, His Majesty the American is such a mixed bag of tones and registers that it can survive a bit of bad comedy, just like it can survive a bit of tedious overplotting. What works, anyway, is terrific: Fairbanks himself, a fearless stuntman who jumps and hangs from roofs and rides horses and fights with aplomb, is obviously the best standout, but perhaps surprisingly, he's not the only thing the film has to offer. Henabery's direction is of the lightest, most delicate sort, creating a breezy European fantasy that skips along cheerily through some charming sets and exquisitely gorgeous backdrops of the mountains and towns whose obviously artificial nature only manages to make them cuter and more dear. And while this is a largely actor-proof movie, several of the supporting players are pretty great in their own right, anchoring the human side of a story that Fairbanks, with his somewhat irritating tendency to pose and declaim (no mean feat when your words can't even be head), does not remotely keep from flying into overwrought theatrics.

Amiable enough all in all, though not by itself an argument that we should still care about Fairbanks, or silent Mitteleuropean adventures. Its a film of a sort that we still see plenty of every year: the well-made but wholly unambitious attempt to do well something that was also done well last month, last year, and the year prior, and is entertaining every single time without ever being truly awe-inspiring. It's an altogether unassuming candidate for the historical importance it holds, but that doesn't keep it from being entertaining; it's a pleasurable frolic of a sort that would barely make an impression a week later, let alone 95 years later, though it's still agreeable in its way even through the thick haze of changing styles and artistic priorities. I would want it to be nobody's first silent or first Fairbanks picture, but I certainly don't see how it could ever do anyone harm.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1919

-Erich von Stroheim makes his debut as writer and director with Blind Husbands

-The Miracle Man makes a star of Lon Chaney and his uncanny skill with make-up

-Cecil B. DeMille and Gloria Swanson work together for the first time on Don't Change Your Husband

Elswehere in world cinema in 1919

-The British First Men in the Moon is the first official adaption of a work by H.G. Wells to film

-Fight for Justice, a filmed play, is traditionally held to be the first Korean film production

-The first important World War I film, Abel Gance's J'accuse, is released in France

For much of the Golden Age of the Hollywood studio system, the contract players in thrall to the executives devoted much of their time to finding ways to exert some kind of independence over what projects they would make and how they would be presented. Of the many individual attempts to break out in some little way from the seemingly immovable strictures of the big studios, perhaps no effort was so bold, or so far-reaching in its effects, as the formation of United Artists in 1919. The artists who were so uniting were four of the biggest names in American film at that time: superstar Mary Pickford, the most bankable human being in the world; her lover, the comedy-adventure star Douglas Fairbanks; D.W. Griffith, possibly the only director at that time who was his own brand name; and Charles Chaplin, multi-hyphenate talent and the only person in the movies who could challenge Pickford's fame and financial success. The idea was to create an independent production and distribution company that would allow these four mega-celebrities to work on their own terms, and while the experiment in its pure form didn't live very long (Griffith abandoned ship in 1924, while Fairbanks and Pickford saw their careers implode in the sound era, and Chaplin quickly became the sort of methodical, fussy artist who took years in between projects to get them right), the idea of an independent studio has never entirely died off since then, and United Artists itself continues to struggle along, though it exists at this time mostly as a shell company for creating James Bond pictures.

The first film released by United Artists, in the latter half of 1919, was the Fairbanks vehicle His Majesty the American. Then as now, Hollywood likes a sure thing more than a genuine gamble, especially if the sure thing can be made to look like a risk, and accordingly, UA aimed to get things started on a safe foot by releasing the kind of film that had been a hit in the past. At that time, Fairbanks was celebrated for his bubbly comedies set in milieus that gave him amble room to showcase his estimable skills as a physical performer, as much an acrobat as an actor. Those who know Fairbanks mostly as the sword-wielding star of costume dramas - which is just about everybody at this point, I suppose - would certainly be staggered by His Majesty the American, which does eventually become a quick-cutting adventure film of the sort he'd become even more famous for in the decade to follow, but only after spending plenty of time as a startling hybrid of political thriller in a Ruritanian principality, fish-out-of-water comedy, boys' own adventure, romantic comedy, and showcase for Fairbanks's skill divorced from narrative or genre. Hell, you don't even need to drag the star's persona into it: to modern eyes, the feverish assemblage of tones and narrative threads would be peculiar regardless of who was headlining the project. But as much as anything, that merely showcases what a freewheeling sense of the rules that still pertained as the '10s gave way to the '20s.

On the other hand, His Majesty the American is perhaps the first film I have turned to in this Hollywood Century project that largely resembles the kind of filmmaking that we're used to all these long decades later. The shots used are still considerably wider than anything in modern cinema: the proscenium-style compositions that define the middle silent era had a few more years of life in them. But the way those shots are broken up into inserts and close-ups, while a bit stiff at times, feels downright radical compared to movies made just one or two years earlier (something must have been in the water: Griffith's Broken Blossoms, typically agreed as having the first totally modern insert shots in American cinema, was UA's very next release). It is perhaps for this reason that the blithe mixture of genres and plots in the movie stands out so bluntly: the film has enough of a contemporary flow that it feels like it ought to behave like a contemporary film in other ways.

All that's a lot of verbiage to throw at a pleasant slip of a thing that isn't really very distinctive in any way you could name. It is, first and above all, a Fairbanks picture, meaning that most of what happens is at some level a contrivance designed to put Fairbanks in positions to show off. In this case, he plays Bill Brooks, a well-to-do New Yorker who has no idea where he came from or who his parents are, but somebody in his past is keeping an eye on him and throwing enough cash at him that he has no real worries in life and is able to pursue his passion to have adventures as an amateur fireman and policeman. We see each of these in setpieces staged with quite a lot of vigor and kinetic energy by writer-director Joseph Henabery (his fourth consecutive Fairbanks picture, near the start of a career that would include dozens and dozens of movies into the late '40s), with the burning tenement building that opens the film a particular standout of effects work and action choreography, setpieces that moreover make not the smallest effort to work themselves into the plot of the rest of the film, and are clearly just there as spectacle for spectacle's sake (talk about feeling modern). Eventually, the story rather arbitrarily packs Bill off to Mexico, to seek out ever more exciting adventures, and that's where he's contacted by representatives of the government of Alaine, a small kingdom in the European Alps currently experiencing some tension over the succession, with King Philippe (Sam Sothern) trying to democritise the country as Grand Duke Sarzeau (Frank Campeau) schemes none too subtly to destablise the king's position. Bill quickly ends up head-over-heels in dynastic intrigue, while also crossing paths with the lovely countess Felice (Marjorie Daw), proving to be the hero of the Alaine people in multiple ways involving greater and smaller demonstrations of swashbuckling and daring.

It's all a bit foggy in expression, though how much of that is the film and how much the heavily beat-up print that I was able to watch it in is up for debate. What's always clear, though, is that the film is first and foremost about Fairbanks, and in that regard it's largely, though not uniformly successful. There's the not-insignificant matter of the frequent cutaways in the first half or so of the film, before Bill arrives in Alaine, where the film spends minutes at a time dramatising the minutiae of politics in a made-up country with a zealous care that could only appeal to a filmgoing population still high on its love affair with Anthony Hope's 1894 novel The Prisoner of Zenda (which had been filmed twice in the 1910s). These scenes deaden a film that wages everything on being so fast and fizzy that we don't stop to notice the threadbare characters or muddy story, and it takes an awfully long time for the film to find its rhythm.

Once it does, it becomes a lot easier to notice the even bigger and more serious problem, one that maybe speaks to the changing nature of tastes over the years and maybe simply my own: Douglas Fairbanks isn't a terribly good comedian. Obviously, audiences in the '10s who made him a superstar on similar hybrids of comedy and adventure would disagree with me on that point, and I do not think it has anything to do with him. The problem is, simply, that he doesn't have a funny face. Look at the great comics of the same era whose work has remained more or less popular: Chaplin had his fussy, twitchy expressions and his absurd greasepaint hair; Buster Keaton his long face and unfazed, modestly unsettled expressions; Harold Lloyd's rubbery mouth and bright, open eyes; Fatty Arbuckle's round pie face with its tight little smile. Fairbanks, not yet boasting his matinee idol mustache, looks emphatically normal, with a bit prominent of a forehead and a slightly wider face than ordinary; he looks like the most handsome man in the real estate office. He certainly doesn't look like someone who should do the face-pulling and wacky activity he's called upon to do, and in such a visual medium, not looking funny is awfully close to not being funny.

Still and all, His Majesty the American is such a mixed bag of tones and registers that it can survive a bit of bad comedy, just like it can survive a bit of tedious overplotting. What works, anyway, is terrific: Fairbanks himself, a fearless stuntman who jumps and hangs from roofs and rides horses and fights with aplomb, is obviously the best standout, but perhaps surprisingly, he's not the only thing the film has to offer. Henabery's direction is of the lightest, most delicate sort, creating a breezy European fantasy that skips along cheerily through some charming sets and exquisitely gorgeous backdrops of the mountains and towns whose obviously artificial nature only manages to make them cuter and more dear. And while this is a largely actor-proof movie, several of the supporting players are pretty great in their own right, anchoring the human side of a story that Fairbanks, with his somewhat irritating tendency to pose and declaim (no mean feat when your words can't even be head), does not remotely keep from flying into overwrought theatrics.

Amiable enough all in all, though not by itself an argument that we should still care about Fairbanks, or silent Mitteleuropean adventures. Its a film of a sort that we still see plenty of every year: the well-made but wholly unambitious attempt to do well something that was also done well last month, last year, and the year prior, and is entertaining every single time without ever being truly awe-inspiring. It's an altogether unassuming candidate for the historical importance it holds, but that doesn't keep it from being entertaining; it's a pleasurable frolic of a sort that would barely make an impression a week later, let alone 95 years later, though it's still agreeable in its way even through the thick haze of changing styles and artistic priorities. I would want it to be nobody's first silent or first Fairbanks picture, but I certainly don't see how it could ever do anyone harm.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1919

-Erich von Stroheim makes his debut as writer and director with Blind Husbands

-The Miracle Man makes a star of Lon Chaney and his uncanny skill with make-up

-Cecil B. DeMille and Gloria Swanson work together for the first time on Don't Change Your Husband

Elswehere in world cinema in 1919

-The British First Men in the Moon is the first official adaption of a work by H.G. Wells to film

-Fight for Justice, a filmed play, is traditionally held to be the first Korean film production

-The first important World War I film, Abel Gance's J'accuse, is released in France