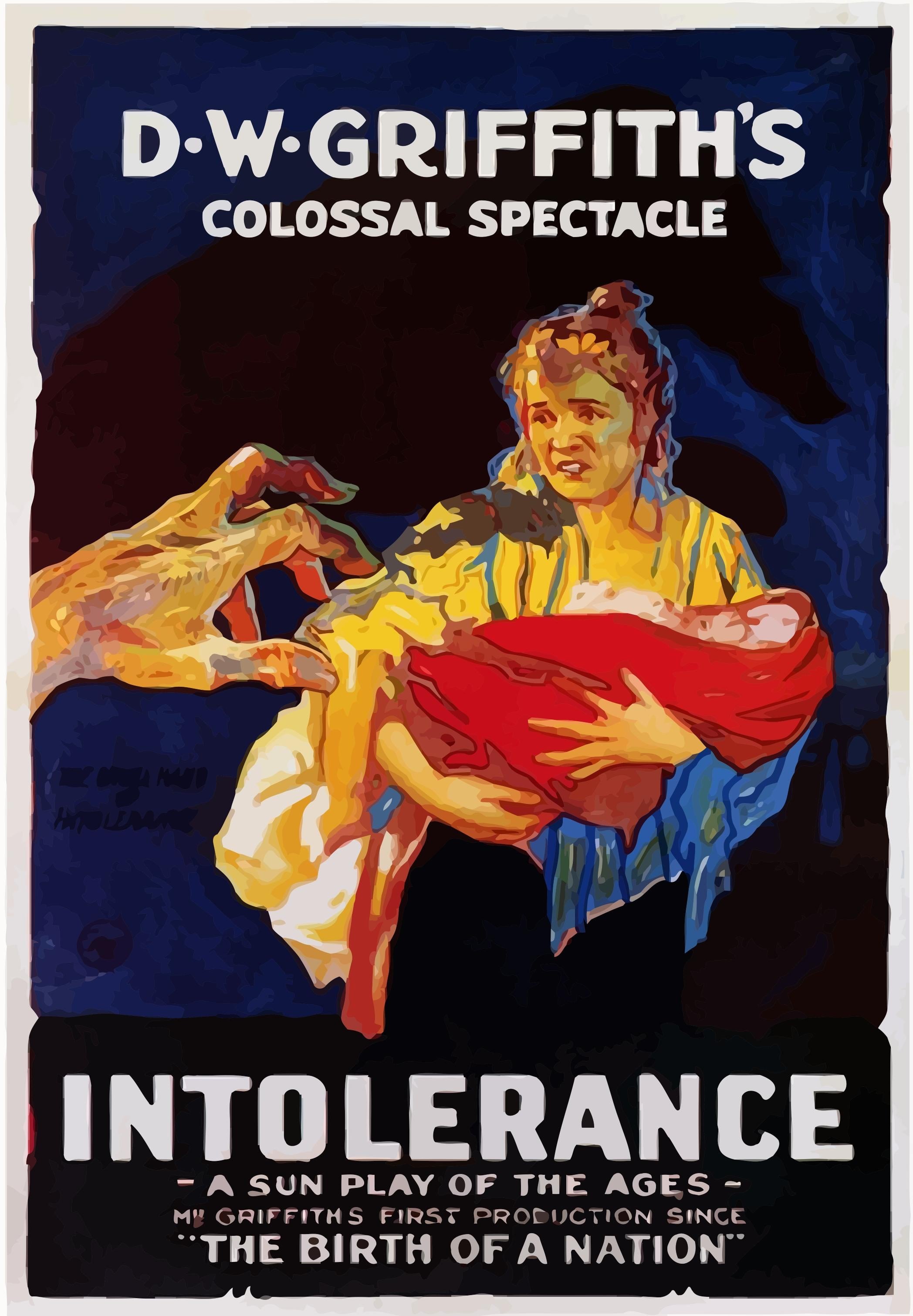

Hollywood Century, 1916: In which Hollywood’s ability to create worlds of unprecdented scale, creativity, and boldness is put to an absurd test

It is generally agreed that D.W. Griffith's 1916 epic Intolerance: A Sun Play of the Ages (also subtitled Love's Struggle Throughout the Ages, if that's the way you roll) was made because of the reaction to his The Birth of a Nation from the year prior, though the exact reason behind that because is a little fuzzy. Some say it was an apology, with Griffith making a film decrying intolerance as a way of making up for the controversy caused by his maddeningly intolerant movie that set race relations back a half-century; some say it was him smacking down the critics who were intolerant towards him and his enthusiastic tolerance of the Ku Klux Klan. Both of these possibilities miss the forest for the trees, though since the real motivation behind Intolerance, as I see it was the 1914 Italian epic Cabiria, and Griffith's feeling that American cinema needed a gigantic historical film of its very own.

That being said, Intolerance didn't begin life as a costume drama at all, but as a characteristic Griffith modern-day melodrama called The Mother and the Law, investigating the cruel behavior of self-appointed social reformers whose bigoted approach to correcting the sins of others would be directly responsible for all the many awful things done to and by a young married couple. From this, the film ballooned into a history-spanning spectacle that looked at intolerance in four periods: the modern day of America before the First World War, France in the 1570s, at the time of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, the Judea that turned on Jesus Christ and crucified him for his message of peace, and Babylon in the 6th Century BCE. The final version of the film, sliding between the four time periods with a rhythm that steadily increases as it progresses, with more and more specific thematic, narrative, and visual overlap in the cross-cutting as well, was so unutterably radical in 1916 (and, to be totally fair, it largely remains so), the film was obliged to open with what amounts to onscreen instructions for how to watch it, title cards that methodically explain how the structure is going to work and why it's not weird.

The sheer magnificent ambition and complexity of Intolerance were by no means unprecedented, but there had probably no film to combine so many elements in such grandiose ways: if The Birth of a Nation demonstrated the sheer scale and effect to which the relatively new technique of cross-cutting could be employed (a technique which Griffith did not first invent, as is often claimed, though he may well have invented it independently), Intolerance takes that demonstrations into even more bravura places. It is, undoubtedly, the case that we tend to prefer talking about Intolerance because unlike the more objectively important earlier film, it's not horrifyingly uncomfortable to watch or even think about by contemporary standards; but I would absolutely claim for it the further merit that even if we remove representational issues from the equation entirely, it's still by far the more accomplished and exciting movie.

All of which is not to say that it's flawless, because no film of such a massive length could be flawless (as to what that length is meant to be: it's pretty hard to say for certain. Different prints have different total lengths, and on disc there's the added issue that not every version has the right projection speed - for reference, I watched the recent Cohen Film Group Blu-ray that presents the movie in astoundingly beautiful clarity, but is visibly running it too fast, and runs for 2:47:32, including restoration credits). There's a reason that you only ever see stills from the modern day and Babylon sequences (both of which were turned into independent features in 1919, the former under the original The Mother and the Law title), which is that the film is far more interested in them in every way. The material pertaining to the Crucifixion occupies such a marginal amount of the running time, and is presented with such narrative dis-cohesion that I have to wonder why Griffith even bothered.

At the same time, as busy and overwrought and sometimes melodramatically clumsy as Intolerance can be, those kinds of considerations are well and truly beside the point: this was clearly not conceived as a sleek, effective narrative or even an exploration of character psychology, but as a tremendous, overwhelming experience. It is in this regard the natural extension of everything that Griffith had done before; he was at all times and in all ways a director more concerned with walloping the viewer emotionally than in the niceties of how he did that. Certainly, just to look at Intolerance, we find a remarkable mixture of some truly sophisticated, forward-thinking filmmaking techniques along with sentimental touches that are caveman-like in their inelegance. Sometimes they happen at exactly the same time: twice the director introduces one of his female leads in a pathetic medium shot, then immediately cutting to a close-up of her face in a flat-out beatifying gesture. We have at once the relatively cutting-edge use of inserts, used in service of hoary "LOOK AT THE PITIABLE WOMEN OF GREAT FEELING AND MORALITY" sentiments that, even by 1916, were a bona fide Griffith cliché as much as Spielberg films with people looking in awe at something glowing or Wes Anderson films with people standing directly in the center of the frame looking straight at the camera are today.

But who would want it any other way? Intolerance works because it is so vigorously, achingly earnest about everything. It believes passionately in its message and in the florid way it chooses to present it.

I have somehow managed to get this far while only suggesting the most abstract shape of the plot. In the 1910s, a moral scold and social activitist named Mary Jenkins (Vera Lewis) wants money with which to do good; she thus cajoles her brother (Sam de Grasse) into raising funds for her, which he does by cutting wages at his mill. This has the effect of putting a pinch on all his employees, including a Boy (Robert Harron), who is in love with the Dear One (Mae Marsh), whose father (Fred Turner) is also employed at the mill. The Boy and the Dear One marry and have a child, but this only increases their miseries, as he turns to crime to try and make ends meet. She struggles on, but the same puritanical forces whose misguided sense of charity led to her current state are not terribly keen on her mothering skills. In 1570s France, against the background of the struggles between queen mother Catherine de Medici (Josephine Crowell), a Catholic, and nobleman Gaspard de Coligny (Joseph Henabery), a Huguenot, the young Huguenot girl Brown Eyes (Margery Wilson) and her beloved, Prosper Latour (Eugene Pallette) prepare to wed, little realising the the religious schism in France is about to erupt in brutal violence against their faith. In Babylon, against a different religious struggle, between the worshipers of Ishtar and Bel-Marduk, the Mountain Girl (Constance Talmadge) tries to find her way through the garish city at the height of its influence and splendor under the control of Belshazzar (Alfred Paget). And in the deeply undernourished Biblical sequence, Jesus Christ (Howard Gaye) plays his greatest hits, with little plot connecting them. Seriously, it's a really dodgy attempt at dramatising the Gospels, until the Crucifixion, which at long last is well integrated into the film's overall scheme.

Does that sound complicated and dense as all hell? It sort of its, but Griffith and his co-editors, James Smith and Ross Smith, make it flow surprisingly cleanly and smoothly, gliding between segments with shots of the Eternal Mother (Griffith favorite Lillian Gish) rocking the cradle of human history. They slowly ramp up the energy of each sequence until the final two reels are a non-stop flurry of some of the best action that survives from the 1910s: the massacre of the Huguenots, an assault on Babylon by Persian King Cyrus (George Siegmann), a race against time and a train to prevent the Boy's unjust hanging, and the march to the Crucifixion all spinning together in a frenzy of excitement that has very little to do with intolerance, or with the melodramatic situations baking for the previous two hours, but is really top-shelf filmmaking.

That, to me, is the film's secret, of sorts: for all that Griffith wanted to make a gigantic epic of feelings and themes and spirituality, a tremendous monument to the humans who have died because of intolerance and those who have beaten it, the film is always at its best when it's going for pure experiential dazzle. The most impressive filmmaking technique, the most memorable images, and the most gobsmacking sets are all clustered in the Babylon story, and Griffith knows it: there are slow tracking shots and grand, stately crane shots whose sole purpose is to pull us into the lavish world populated by thousands of extras, and this at a time when tracking shots and crane shots were rare as hen's teeth. These are surprisingly fresh moments, inviting us to partake of their spectacle just as readily as Avatar did 93 years later. And it works - if I have any reservation, it's that the Babylon and France sequences are both spoiled a bit by anachronistic acting and even more anachronistic make-up, which makes them always seem like a dress-up party from 1916, and not a real attempt at bringing history to life, which became the goal of costume dramas even by the end of the silent era.

Still, spectacle and all, the best part of the film is probably the modern sequence, and not just because Mae Marsh is giving far and away the best performance, and the Dear One is far and away the most vividly sketched of the film's many deliberately archetypal protagonists. It's the segment closest to Griffith's previous work, and his increased comfort is palpable, even if he's never as inventive with the camera here as in the Babylon scenes. Certainly, on a narrative level, the modern plot is the only one that feels, start-to-finish, like a complete and coherent object; it is, in fact, the only one that feels like it's telling a story, and not simply rotating through moments in a story being kept just out of view. Not that such things are necessarily a huge consideration in a film so exuberantly alive with spectacular images and propulsive editing rhythms; narrative is a third-tier consideration here, fourth if we can agree that it's also subordinated to the grandiose acting on display.

It is, at any rate, a jaw-dropping thing to watch, massive and physically robust in a way that few epics ever have been, even at the height of the '50s and '60s vogue for the things. In all four sequences, this is a visibly titanic, expensive production, and even though it was a hit in 1916, it still didn't come close to making back its budget, pitching the year-old Triangle Motion Picture Company into the jaws of bankruptcy, and eventually leading it to be folded into Paramount. But so many decades after everybody involved has died, we needn't concern ourselves with that; instead, we can merely gawk and stare at the first great example of what the Hollywood entertainment factory could achieve when you threw money at it like there was no tomorrow.

A final note: this was, I think, the first silent film I ever saw; it was certainly the first one not starring Charles Chaplin. I don't know that I'd recommend it serve that function in anyone's life - it's long and unapologetically sentimental - but it seems to have worked out well for me, so I guess I don't know what to say. But it would have felt wrong not to nod my head in its direction, for filling such a key role in my cinephilic development.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1916

-The first feature-length adaptation of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea pioneers underwater cinematography

-Charles Chaplin directs One A.M., the first of his films to seriously explore the possibilities of the medium

-The version of Snow White that made a young Walt Disney fall in love with the story opens

Elsewhere in world cinema in 1916

-The escalating war in Europe has a significant negative impact on film production on that continent. It is because of the reduction of native-made films at this time and up to the beginning of the 1920s that American-made films gained an early economic toehold overseas

-Zhang Shi-chuan establishes the first film production company in China

That being said, Intolerance didn't begin life as a costume drama at all, but as a characteristic Griffith modern-day melodrama called The Mother and the Law, investigating the cruel behavior of self-appointed social reformers whose bigoted approach to correcting the sins of others would be directly responsible for all the many awful things done to and by a young married couple. From this, the film ballooned into a history-spanning spectacle that looked at intolerance in four periods: the modern day of America before the First World War, France in the 1570s, at the time of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, the Judea that turned on Jesus Christ and crucified him for his message of peace, and Babylon in the 6th Century BCE. The final version of the film, sliding between the four time periods with a rhythm that steadily increases as it progresses, with more and more specific thematic, narrative, and visual overlap in the cross-cutting as well, was so unutterably radical in 1916 (and, to be totally fair, it largely remains so), the film was obliged to open with what amounts to onscreen instructions for how to watch it, title cards that methodically explain how the structure is going to work and why it's not weird.

The sheer magnificent ambition and complexity of Intolerance were by no means unprecedented, but there had probably no film to combine so many elements in such grandiose ways: if The Birth of a Nation demonstrated the sheer scale and effect to which the relatively new technique of cross-cutting could be employed (a technique which Griffith did not first invent, as is often claimed, though he may well have invented it independently), Intolerance takes that demonstrations into even more bravura places. It is, undoubtedly, the case that we tend to prefer talking about Intolerance because unlike the more objectively important earlier film, it's not horrifyingly uncomfortable to watch or even think about by contemporary standards; but I would absolutely claim for it the further merit that even if we remove representational issues from the equation entirely, it's still by far the more accomplished and exciting movie.

All of which is not to say that it's flawless, because no film of such a massive length could be flawless (as to what that length is meant to be: it's pretty hard to say for certain. Different prints have different total lengths, and on disc there's the added issue that not every version has the right projection speed - for reference, I watched the recent Cohen Film Group Blu-ray that presents the movie in astoundingly beautiful clarity, but is visibly running it too fast, and runs for 2:47:32, including restoration credits). There's a reason that you only ever see stills from the modern day and Babylon sequences (both of which were turned into independent features in 1919, the former under the original The Mother and the Law title), which is that the film is far more interested in them in every way. The material pertaining to the Crucifixion occupies such a marginal amount of the running time, and is presented with such narrative dis-cohesion that I have to wonder why Griffith even bothered.

At the same time, as busy and overwrought and sometimes melodramatically clumsy as Intolerance can be, those kinds of considerations are well and truly beside the point: this was clearly not conceived as a sleek, effective narrative or even an exploration of character psychology, but as a tremendous, overwhelming experience. It is in this regard the natural extension of everything that Griffith had done before; he was at all times and in all ways a director more concerned with walloping the viewer emotionally than in the niceties of how he did that. Certainly, just to look at Intolerance, we find a remarkable mixture of some truly sophisticated, forward-thinking filmmaking techniques along with sentimental touches that are caveman-like in their inelegance. Sometimes they happen at exactly the same time: twice the director introduces one of his female leads in a pathetic medium shot, then immediately cutting to a close-up of her face in a flat-out beatifying gesture. We have at once the relatively cutting-edge use of inserts, used in service of hoary "LOOK AT THE PITIABLE WOMEN OF GREAT FEELING AND MORALITY" sentiments that, even by 1916, were a bona fide Griffith cliché as much as Spielberg films with people looking in awe at something glowing or Wes Anderson films with people standing directly in the center of the frame looking straight at the camera are today.

But who would want it any other way? Intolerance works because it is so vigorously, achingly earnest about everything. It believes passionately in its message and in the florid way it chooses to present it.

I have somehow managed to get this far while only suggesting the most abstract shape of the plot. In the 1910s, a moral scold and social activitist named Mary Jenkins (Vera Lewis) wants money with which to do good; she thus cajoles her brother (Sam de Grasse) into raising funds for her, which he does by cutting wages at his mill. This has the effect of putting a pinch on all his employees, including a Boy (Robert Harron), who is in love with the Dear One (Mae Marsh), whose father (Fred Turner) is also employed at the mill. The Boy and the Dear One marry and have a child, but this only increases their miseries, as he turns to crime to try and make ends meet. She struggles on, but the same puritanical forces whose misguided sense of charity led to her current state are not terribly keen on her mothering skills. In 1570s France, against the background of the struggles between queen mother Catherine de Medici (Josephine Crowell), a Catholic, and nobleman Gaspard de Coligny (Joseph Henabery), a Huguenot, the young Huguenot girl Brown Eyes (Margery Wilson) and her beloved, Prosper Latour (Eugene Pallette) prepare to wed, little realising the the religious schism in France is about to erupt in brutal violence against their faith. In Babylon, against a different religious struggle, between the worshipers of Ishtar and Bel-Marduk, the Mountain Girl (Constance Talmadge) tries to find her way through the garish city at the height of its influence and splendor under the control of Belshazzar (Alfred Paget). And in the deeply undernourished Biblical sequence, Jesus Christ (Howard Gaye) plays his greatest hits, with little plot connecting them. Seriously, it's a really dodgy attempt at dramatising the Gospels, until the Crucifixion, which at long last is well integrated into the film's overall scheme.

Does that sound complicated and dense as all hell? It sort of its, but Griffith and his co-editors, James Smith and Ross Smith, make it flow surprisingly cleanly and smoothly, gliding between segments with shots of the Eternal Mother (Griffith favorite Lillian Gish) rocking the cradle of human history. They slowly ramp up the energy of each sequence until the final two reels are a non-stop flurry of some of the best action that survives from the 1910s: the massacre of the Huguenots, an assault on Babylon by Persian King Cyrus (George Siegmann), a race against time and a train to prevent the Boy's unjust hanging, and the march to the Crucifixion all spinning together in a frenzy of excitement that has very little to do with intolerance, or with the melodramatic situations baking for the previous two hours, but is really top-shelf filmmaking.

That, to me, is the film's secret, of sorts: for all that Griffith wanted to make a gigantic epic of feelings and themes and spirituality, a tremendous monument to the humans who have died because of intolerance and those who have beaten it, the film is always at its best when it's going for pure experiential dazzle. The most impressive filmmaking technique, the most memorable images, and the most gobsmacking sets are all clustered in the Babylon story, and Griffith knows it: there are slow tracking shots and grand, stately crane shots whose sole purpose is to pull us into the lavish world populated by thousands of extras, and this at a time when tracking shots and crane shots were rare as hen's teeth. These are surprisingly fresh moments, inviting us to partake of their spectacle just as readily as Avatar did 93 years later. And it works - if I have any reservation, it's that the Babylon and France sequences are both spoiled a bit by anachronistic acting and even more anachronistic make-up, which makes them always seem like a dress-up party from 1916, and not a real attempt at bringing history to life, which became the goal of costume dramas even by the end of the silent era.

Still, spectacle and all, the best part of the film is probably the modern sequence, and not just because Mae Marsh is giving far and away the best performance, and the Dear One is far and away the most vividly sketched of the film's many deliberately archetypal protagonists. It's the segment closest to Griffith's previous work, and his increased comfort is palpable, even if he's never as inventive with the camera here as in the Babylon scenes. Certainly, on a narrative level, the modern plot is the only one that feels, start-to-finish, like a complete and coherent object; it is, in fact, the only one that feels like it's telling a story, and not simply rotating through moments in a story being kept just out of view. Not that such things are necessarily a huge consideration in a film so exuberantly alive with spectacular images and propulsive editing rhythms; narrative is a third-tier consideration here, fourth if we can agree that it's also subordinated to the grandiose acting on display.

It is, at any rate, a jaw-dropping thing to watch, massive and physically robust in a way that few epics ever have been, even at the height of the '50s and '60s vogue for the things. In all four sequences, this is a visibly titanic, expensive production, and even though it was a hit in 1916, it still didn't come close to making back its budget, pitching the year-old Triangle Motion Picture Company into the jaws of bankruptcy, and eventually leading it to be folded into Paramount. But so many decades after everybody involved has died, we needn't concern ourselves with that; instead, we can merely gawk and stare at the first great example of what the Hollywood entertainment factory could achieve when you threw money at it like there was no tomorrow.

A final note: this was, I think, the first silent film I ever saw; it was certainly the first one not starring Charles Chaplin. I don't know that I'd recommend it serve that function in anyone's life - it's long and unapologetically sentimental - but it seems to have worked out well for me, so I guess I don't know what to say. But it would have felt wrong not to nod my head in its direction, for filling such a key role in my cinephilic development.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1916

-The first feature-length adaptation of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea pioneers underwater cinematography

-Charles Chaplin directs One A.M., the first of his films to seriously explore the possibilities of the medium

-The version of Snow White that made a young Walt Disney fall in love with the story opens

Elsewhere in world cinema in 1916

-The escalating war in Europe has a significant negative impact on film production on that continent. It is because of the reduction of native-made films at this time and up to the beginning of the 1920s that American-made films gained an early economic toehold overseas

-Zhang Shi-chuan establishes the first film production company in China