The mothering instinct

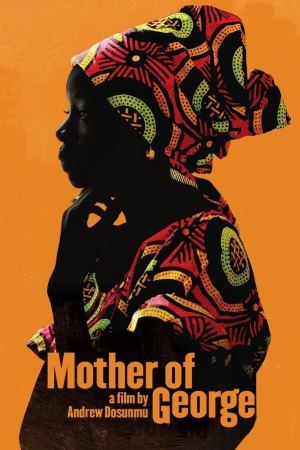

Bradford Young! Say it soft, and it's not really at all like praying, with those two shovey "D"s and all, but it's still an exquisite and important name to get to know. I feel as if Young has been my big discovery of the year, which is bad on me, since 2013 is not also the first year of prominent movies to be shot by him - going all the way back to 2011, he was the cinematographer on Pariah, a film that even had some pretty damn noteworthy cinematography. But the back half of 2013 has been as revelatory for Young as 2012 was for Greig Fraser: in the span of less than two months, Young saw the release of Ain't Them Bodies Saints and Mother of George, two outstandingly confident and sophisticated examples of the cinematographer's art utilising two entirely different stylistic handbooks; they are similar only in that they are both among the year's most beautiful films. Of the two, Mother of George is the even more exciting and innovate piece of work, for while Ain't Them Bodies Saints is essentially a tremendously gifted act of pastiche (the question seems to have been, "Can you do ersatz Lubezki?", and the answer came back "Hells to the yes, motherfucker"), Mother of George is made up more complicated and challenging images which are brought more to the foreground by a film whose narrative and psychological concepts are expressed primarily through visual means. It's also the third film I can personally vouch for, after Pariah and Middle of Nowhere, in which Young establishes himself as our reigning genius in the nearly empty field of making cunningly-lit images chiefly populated by people with very dark brown skin.

And for all that, I can't even say that Young is the obvious MVP of a movie which would quite fail without him, for Mother of George is an awfully great piece of filmmaking that makes excellent use of many talented people. The most readily apparent of these is probably Danai Gurira as the titular figure, though George exists as a more conjectural figure to have a mother than an actual flesh and blood person. The plot, which does not make any significant attempt to surprise, goes about like this: Adenike (Gurira) and Ayodele (Isaach De Bankolé) are members of the Yoruba immigrant community in Brooklyn, and the film opens with their marriage. At this joyful event, Ayodele's mother (Bukky Ajayi) blesses Adenike with a prayer that sounds awfully like a command: they will have a child, it will be a boy, and he will be named George. 18 months later, Adenike is not pregnant, and starting to go from panicked to soul-despairing; worse yet, the deep-set conservatism of the tradition-addicted Yoruba community means that Ayodele is openly antagonistic to Adenike's pleas to go to a fertility doctor and see what's going on. Eventually, her mother-in-law, acting from a position of dictatorial kindness, raises a suggestion that seems perfectly reasonable given her cultural preoccupations, and totally horrifying to the more Americanised Adenike: sleep with Ayodele's brother Biyi (Anthony Okungbowa), get pregnant that way, and never bother telling a soul, because it's all the same bloodline, and it doesn't count as infidelity.

It is not the world's most flexible story, true, but if anything, that works in its favor. This is above all things a story of conflict between sub-Saharan African tradition and modern American social codes, both at the plot level of family drama and the psychological level of character study of Adenike's increasingly desperate state. And the primary way that director-writer Andrew Dosunmu works this out is through a highly presentational and theatrical - a hater might describe it as "stagey" - evocation of a certain kind of exoticised African-ness. Or at least, what sub-Saharan African cinema presents as African-ness. It is a film in which the eye-searing colors and heightened drama of a certain thread of African cinema is situated in places where we'd be led to expect an American indie kind of grainy hand-held urban realism, with Dosunmu and Young capturing everything with many arrestingly outré frames that aren't what we'd naturally expect from either. The film is positively rotten with shots in which the camera height is much elevated from anything normal or safe, marginalisng the characters not at the side of the frame, but at the bottom, and in such a way stressing the out-of-placeness Adenike feels in trying to navigate her life in a manner that really stands out and startles us, when other, more standard ways of emphasising "this person doesn't belong here" through the visuals would tend to go in one eye and out the other, if you will.

The most rewarding thing about Mother of George is that its feints towards exoticism are absolutely never as simple as just coding the Yoruba population as a non-American "other" for the audience's convenience, a simple counterpoint to the feisty assimilation practiced by Sade (Yaya DaCosta), Adenike's best friend and the exact counterpoint to her mother-in-law. The bright colors in the sets and particularly in the costumes are always used as a means of pinpointing exactly where we are in the emotional arc of the film, even more than the script does; I half wonder if you could correctly sketch the shape of the drama simply by tracking the costumes Gurira wears throughout. Nor is this the only primarily visual way the film communicates meaning: the evolution of the several sex scenes in the film, from shy passion to routine lovemaking to bitter, mechanical humping, niftily sketches out Adenike's increasing detachment from her life and marriage, and all because of the way that Dosunmu chooses to frame Gurira in each of these moments, and the amount of emptiness she allows to show in her face in each scene. Hell, even the editing is keenly precise: the more cutting within a scene, the more positive and optimistic the mood of that scene - the more life in it, if you will, which is such a stupidly obvious trick that I can't understand why it also seems so rare.

All of this would all be so much aesthetic wankery if it wasn't tied to a clear and vital emotional drama, and this is something that Mother of George absolutely is in every way. It is simple, almost reductive: a woman is devastated that she can't have a child, and this makes her feel like less of a person. But the filmmakers and actors bring that spare skeleton of a drama to life with passion and intensity and beauty, and the dramatically sparse, visually lush film they've collaborated to make is one of the greatest human stories and greatest formal exercises in recent cinematic memory.

And for all that, I can't even say that Young is the obvious MVP of a movie which would quite fail without him, for Mother of George is an awfully great piece of filmmaking that makes excellent use of many talented people. The most readily apparent of these is probably Danai Gurira as the titular figure, though George exists as a more conjectural figure to have a mother than an actual flesh and blood person. The plot, which does not make any significant attempt to surprise, goes about like this: Adenike (Gurira) and Ayodele (Isaach De Bankolé) are members of the Yoruba immigrant community in Brooklyn, and the film opens with their marriage. At this joyful event, Ayodele's mother (Bukky Ajayi) blesses Adenike with a prayer that sounds awfully like a command: they will have a child, it will be a boy, and he will be named George. 18 months later, Adenike is not pregnant, and starting to go from panicked to soul-despairing; worse yet, the deep-set conservatism of the tradition-addicted Yoruba community means that Ayodele is openly antagonistic to Adenike's pleas to go to a fertility doctor and see what's going on. Eventually, her mother-in-law, acting from a position of dictatorial kindness, raises a suggestion that seems perfectly reasonable given her cultural preoccupations, and totally horrifying to the more Americanised Adenike: sleep with Ayodele's brother Biyi (Anthony Okungbowa), get pregnant that way, and never bother telling a soul, because it's all the same bloodline, and it doesn't count as infidelity.

It is not the world's most flexible story, true, but if anything, that works in its favor. This is above all things a story of conflict between sub-Saharan African tradition and modern American social codes, both at the plot level of family drama and the psychological level of character study of Adenike's increasingly desperate state. And the primary way that director-writer Andrew Dosunmu works this out is through a highly presentational and theatrical - a hater might describe it as "stagey" - evocation of a certain kind of exoticised African-ness. Or at least, what sub-Saharan African cinema presents as African-ness. It is a film in which the eye-searing colors and heightened drama of a certain thread of African cinema is situated in places where we'd be led to expect an American indie kind of grainy hand-held urban realism, with Dosunmu and Young capturing everything with many arrestingly outré frames that aren't what we'd naturally expect from either. The film is positively rotten with shots in which the camera height is much elevated from anything normal or safe, marginalisng the characters not at the side of the frame, but at the bottom, and in such a way stressing the out-of-placeness Adenike feels in trying to navigate her life in a manner that really stands out and startles us, when other, more standard ways of emphasising "this person doesn't belong here" through the visuals would tend to go in one eye and out the other, if you will.

The most rewarding thing about Mother of George is that its feints towards exoticism are absolutely never as simple as just coding the Yoruba population as a non-American "other" for the audience's convenience, a simple counterpoint to the feisty assimilation practiced by Sade (Yaya DaCosta), Adenike's best friend and the exact counterpoint to her mother-in-law. The bright colors in the sets and particularly in the costumes are always used as a means of pinpointing exactly where we are in the emotional arc of the film, even more than the script does; I half wonder if you could correctly sketch the shape of the drama simply by tracking the costumes Gurira wears throughout. Nor is this the only primarily visual way the film communicates meaning: the evolution of the several sex scenes in the film, from shy passion to routine lovemaking to bitter, mechanical humping, niftily sketches out Adenike's increasing detachment from her life and marriage, and all because of the way that Dosunmu chooses to frame Gurira in each of these moments, and the amount of emptiness she allows to show in her face in each scene. Hell, even the editing is keenly precise: the more cutting within a scene, the more positive and optimistic the mood of that scene - the more life in it, if you will, which is such a stupidly obvious trick that I can't understand why it also seems so rare.

All of this would all be so much aesthetic wankery if it wasn't tied to a clear and vital emotional drama, and this is something that Mother of George absolutely is in every way. It is simple, almost reductive: a woman is devastated that she can't have a child, and this makes her feel like less of a person. But the filmmakers and actors bring that spare skeleton of a drama to life with passion and intensity and beauty, and the dramatically sparse, visually lush film they've collaborated to make is one of the greatest human stories and greatest formal exercises in recent cinematic memory.