Men of steel

I like to think it went this way: during the filming of Out of the Furnace, a bored Forest Whitaker and Christian Bale were goofing around on set, keeping themselves awake as actors do. And Whitaker decided to break out his impression of Bale's over-the-top gravelly Batman voice while they were goofing around. Unfortunately this ended up being filmed and was an otherwise perfect take, and Whitaker was thus forced to use the voice throughout the rest of the shoot, for continuity purposes. I mean, there has to be some reason that a pro like Whitaker would allow himself to get mired so down deep in such an obviously terrible choice as that accent.

The good news is that neither Whitaker nor his staggering voice are all that important to Out of the Furnace, which is instead a movie about two brothers struggling to get by in an America That Stopped Caring. And the capitals, I promise, are entirely justified by the film's gravely declamatory presentation of post-industrial rural Pennsylvania as a decaying No Man's Land of the skeletons of proud factories and proud industry towns, reduced to hardscrabble populations of desperate people. Not since The Deer Hunter has a movie been so forthright in its desire to use steel mills to represent absolutely everything imaginable besides steel mills.

Aw, I'm giving Out of the Furnace a harder time than it deserves. It is, in fact, a largely successful version of the thing it wants to be, and it even manages to justify some of its biggest ambitions, thanks largely to the skillful location photography of Masanobu Takayanagi, whose insistently unromantic camera leaves poverty looking grubby and sad and not at all picturesque; to Dickon Hinchliffe's frequently redundant but effectively sparse and weary folk-orchestrated score; and to Bale and Casey Affleck as brothers Russell and Rodney Baze, the pair of them capturing something lived-in and essential about the kind of guys who would grow up in such an environment as the tapped-out community where they live and work. Even that's not as complete and deep and perfect as their fraternal push-pull relationship, relaxed with each other, anticipating each other's actions and words, bantering in a lazy manner that exactly nails the notion that these two men are family, despite the complete lack of any visual evidence that they share genes.

In keeping with its Stated Themes, this is a story of bad things happening to largely decent people. When we meet those Baze boys, Russell is a steelworker with a swell gal, Lena (Zoe Saldana), Rodney is on a break between tours in Iraq (it's 2008, and people were still getting dragged back into combat against their will over and over again), and neither one of them has much of a sense of where life is going, but the day-to-day seems to be taking care of itself just fine. Except that in Rodney's case, he's in for a lot of money to the patient but not infinitely saintlike John Petty (Willem Dafoe), a local business owner and gambling fixer. Russell takes care of this situation as best he can, but there comes at this point a car crash, an elevated blood alcohol level, and a dead mother and child. Thus does Russell end up in jail for several years.

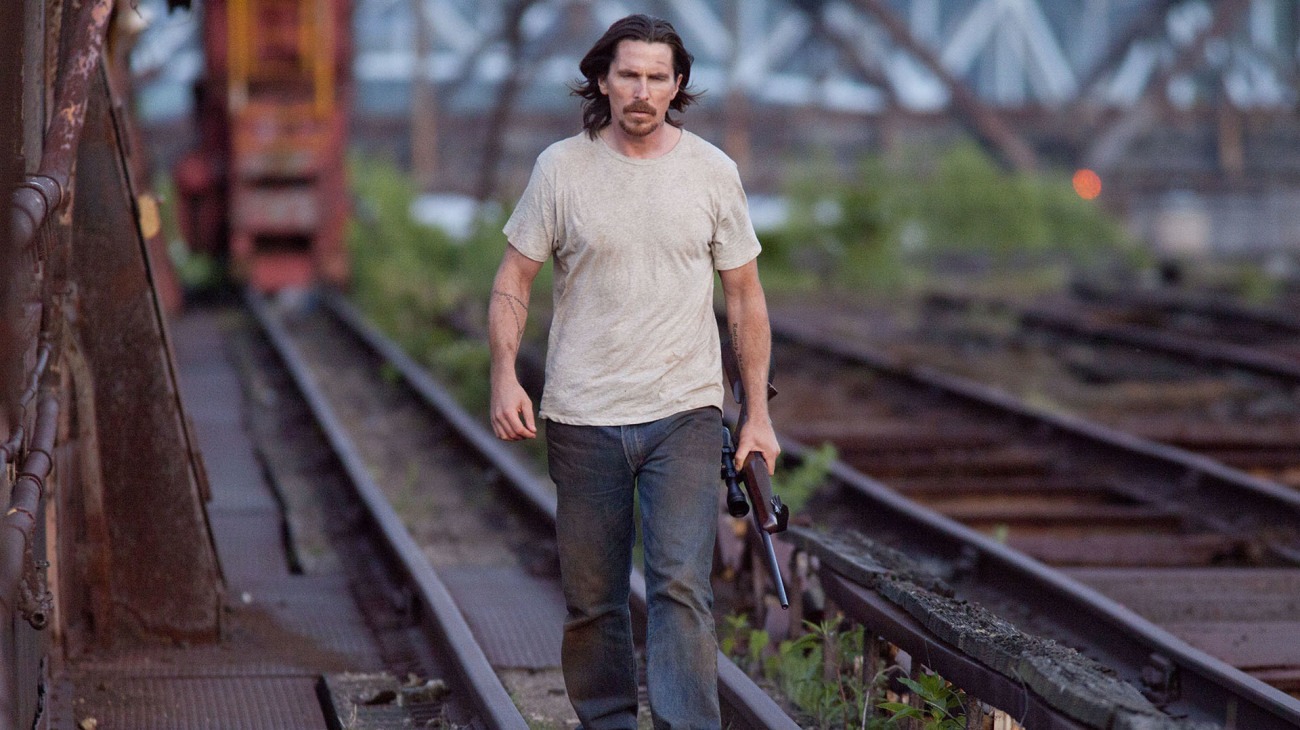

Everything's shitty when he gets out: Lena has hooked up with police chief Barnes (Whitaker), the brothers' dad is dead of cancer, and Rodney is working up a transparently dumb scheme to make enough money to wipe out all his debts by throwing his lot in with the back country psychopath Harlan DeGroat (Woody Harrelson, buoyantly unhinged; I am undecided if this is a good thing or an outrageously terrible one). When the easily-angered druglord takes offense to Rodney and John's activities, he disappears them in the Appalachian woods, and an untethered, soul-despairing Russell tries to reassemble his world the only way that makes sense: hunting Harlan down, finding his brother, and getting revenge.

On the whole, Out of the Furnace is much too dour and fatalistic to be the simple revenge thriller that it seems to set its mind on being, which is absolutely to its benefit: the straightforward version of the story would be unpleasantly fixated on redemptive violence as the cornerstone of masculinity. And it's not entirely free of that (the film's last 45 seconds are befuddling and terrible), but Bale's performance, certainly, goes a long way to muddy the most simplistic possible reading of the scenario. Still, the film gets rougher and more generic as it goes along, and the first half is altogether better, not just because it lacks the po-faced amorality, but because the Bale-Affleck chemistry is the best thing the film has going for it, and when Affleck vanishes from the film, he takes away not just its human spark (which is, anyway, likely intentional), but a lot of what makes it interesting to watch.

This is, after all, a film by director and co-writer (with Brad Ingelsby) Scott Cooper, only his second feature. His first, 2009's Crazy Heart, was another rural American character study, but one that pointedly avoided the Big Questions that lace throughout Out of the Furnace, possessing not a trace of pointed symbolism; and while this makes it a bit less vivid and rich, than the director's sophomore work, it also keeps it from being so bogged down by its own weight. Cooper's great at watching people living life, and that is the primary mode of the better half of Out of the Furnace, and the whole thing noticeably sags when it is called upon to become a genre film.

Sagging, mind you, is very much what Out of the Furnace is about, and I will not pretend that the two portions of the plot are not very much of a piece; it has a clear dividing line, but the tone and style are exactly the same throughout, and it builds its themes and ideas throughout its entire 116-minute running time. It has a focused momentum that carries it through even the stiffest passages of plot (including a long red herring of a road trip), and the sense of place that is the film's best asset after Bale remains firmly intact (as does Bale's performance, for that matter). It ends up being less persuasive and probing than it feels like the opening scenario and setting could have facilitated, but that setting is rich enough to carry over a somewhat contrived storyline or two.

The good news is that neither Whitaker nor his staggering voice are all that important to Out of the Furnace, which is instead a movie about two brothers struggling to get by in an America That Stopped Caring. And the capitals, I promise, are entirely justified by the film's gravely declamatory presentation of post-industrial rural Pennsylvania as a decaying No Man's Land of the skeletons of proud factories and proud industry towns, reduced to hardscrabble populations of desperate people. Not since The Deer Hunter has a movie been so forthright in its desire to use steel mills to represent absolutely everything imaginable besides steel mills.

Aw, I'm giving Out of the Furnace a harder time than it deserves. It is, in fact, a largely successful version of the thing it wants to be, and it even manages to justify some of its biggest ambitions, thanks largely to the skillful location photography of Masanobu Takayanagi, whose insistently unromantic camera leaves poverty looking grubby and sad and not at all picturesque; to Dickon Hinchliffe's frequently redundant but effectively sparse and weary folk-orchestrated score; and to Bale and Casey Affleck as brothers Russell and Rodney Baze, the pair of them capturing something lived-in and essential about the kind of guys who would grow up in such an environment as the tapped-out community where they live and work. Even that's not as complete and deep and perfect as their fraternal push-pull relationship, relaxed with each other, anticipating each other's actions and words, bantering in a lazy manner that exactly nails the notion that these two men are family, despite the complete lack of any visual evidence that they share genes.

In keeping with its Stated Themes, this is a story of bad things happening to largely decent people. When we meet those Baze boys, Russell is a steelworker with a swell gal, Lena (Zoe Saldana), Rodney is on a break between tours in Iraq (it's 2008, and people were still getting dragged back into combat against their will over and over again), and neither one of them has much of a sense of where life is going, but the day-to-day seems to be taking care of itself just fine. Except that in Rodney's case, he's in for a lot of money to the patient but not infinitely saintlike John Petty (Willem Dafoe), a local business owner and gambling fixer. Russell takes care of this situation as best he can, but there comes at this point a car crash, an elevated blood alcohol level, and a dead mother and child. Thus does Russell end up in jail for several years.

Everything's shitty when he gets out: Lena has hooked up with police chief Barnes (Whitaker), the brothers' dad is dead of cancer, and Rodney is working up a transparently dumb scheme to make enough money to wipe out all his debts by throwing his lot in with the back country psychopath Harlan DeGroat (Woody Harrelson, buoyantly unhinged; I am undecided if this is a good thing or an outrageously terrible one). When the easily-angered druglord takes offense to Rodney and John's activities, he disappears them in the Appalachian woods, and an untethered, soul-despairing Russell tries to reassemble his world the only way that makes sense: hunting Harlan down, finding his brother, and getting revenge.

On the whole, Out of the Furnace is much too dour and fatalistic to be the simple revenge thriller that it seems to set its mind on being, which is absolutely to its benefit: the straightforward version of the story would be unpleasantly fixated on redemptive violence as the cornerstone of masculinity. And it's not entirely free of that (the film's last 45 seconds are befuddling and terrible), but Bale's performance, certainly, goes a long way to muddy the most simplistic possible reading of the scenario. Still, the film gets rougher and more generic as it goes along, and the first half is altogether better, not just because it lacks the po-faced amorality, but because the Bale-Affleck chemistry is the best thing the film has going for it, and when Affleck vanishes from the film, he takes away not just its human spark (which is, anyway, likely intentional), but a lot of what makes it interesting to watch.

This is, after all, a film by director and co-writer (with Brad Ingelsby) Scott Cooper, only his second feature. His first, 2009's Crazy Heart, was another rural American character study, but one that pointedly avoided the Big Questions that lace throughout Out of the Furnace, possessing not a trace of pointed symbolism; and while this makes it a bit less vivid and rich, than the director's sophomore work, it also keeps it from being so bogged down by its own weight. Cooper's great at watching people living life, and that is the primary mode of the better half of Out of the Furnace, and the whole thing noticeably sags when it is called upon to become a genre film.

Sagging, mind you, is very much what Out of the Furnace is about, and I will not pretend that the two portions of the plot are not very much of a piece; it has a clear dividing line, but the tone and style are exactly the same throughout, and it builds its themes and ideas throughout its entire 116-minute running time. It has a focused momentum that carries it through even the stiffest passages of plot (including a long red herring of a road trip), and the sense of place that is the film's best asset after Bale remains firmly intact (as does Bale's performance, for that matter). It ends up being less persuasive and probing than it feels like the opening scenario and setting could have facilitated, but that setting is rich enough to carry over a somewhat contrived storyline or two.