Review All Monsters! - Voyage to the bottom of the sea

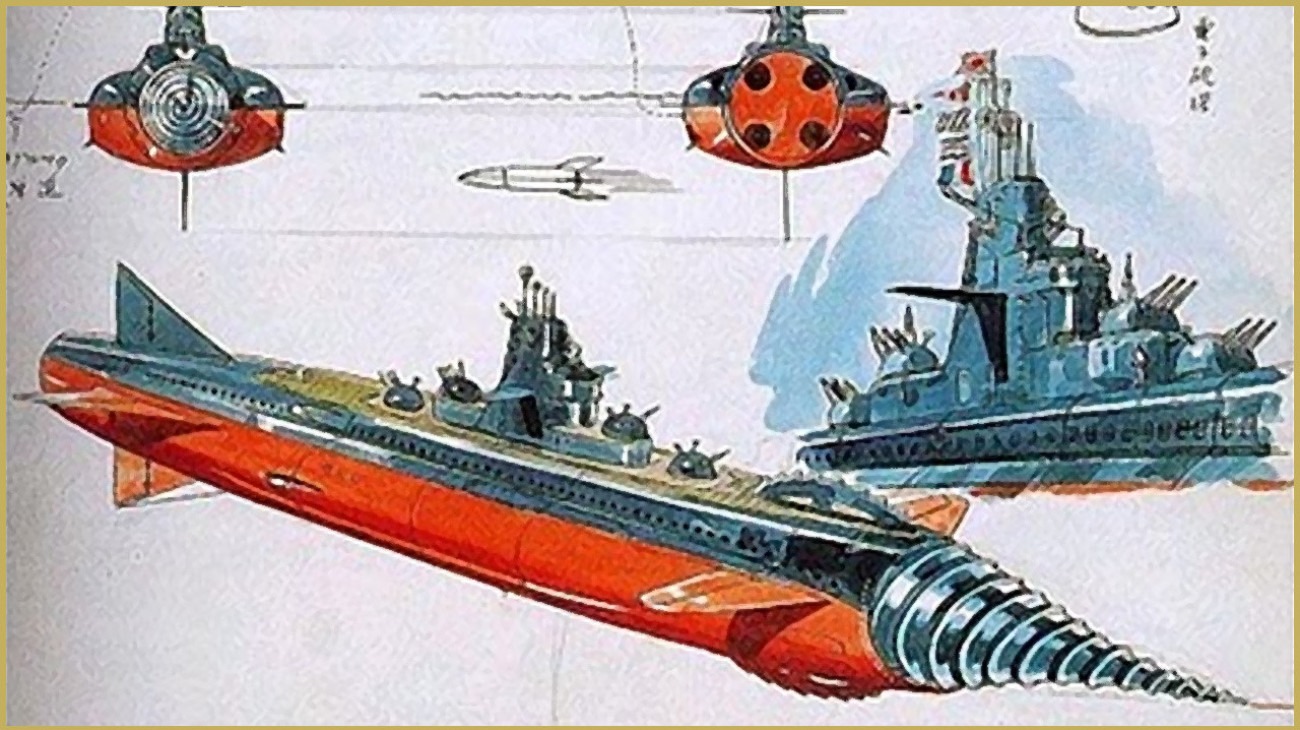

There wasn't, of course, a single moment when Toho ceased to think of the daikaiju eiga as a serious genre for prestigious, big-budget filmmaking, and instead turned it into, basically, kids' stuff. Shifts like that are a process, not an executive decision, and from the vantage point of 1963, we still have a couple unabashedly sincere and relatively grown-up Godzilla films in front of us, at least. But in 1963, we also have the much more present fact of Atragon to deal with, and while something about it leaves me reluctant to stuff it into the kiddie ghetto, necessarily (there's at least some psychological nuance in all the human drama going around, and the film's relationship to World War II is awfully damn tricky), there's no denying that to a large degree, this movie feels like a feature-length ad campaign for a toy submarine. Let's be clear - a goddamn amazing toy submarine that would have made its owner the envy of all the backyard pools in the neighborhood. Let's also be clear - as far as I'm aware, the submarine that gives the film it's English title (the Japanese translates to Undersea Warship) was not made into a toy, which seems like a most pathetic waste.

Still and all, the effect of the whole movie is, vividly, that the Atragon (in the English dub), AKA Goten-go (the original Japanese),* is so freaking cool that it's not fair. Indeed, this is to no small degree the main point of contention driving the entire narrative. Also, it was adapted from a series of novels written by Oshikawa Shunrō in the first decade of the 20th Century that were openly targeting a juvenile audience, which would seem to seal the deal: Atragon is a movie about the most awesomely bad-ass super-submarine ever, and it even fights a freaking underwater dragon, man. It's a movie for boys on the hunt for awesome sci-fi spectacle, basically, though since that spectacle exists in the form in which it was practiced in Japan in 1963, I don't imagine that the 12-year-olds of the 21st Century would get anything vaguely resembling the pleasure out of Atragon that their dads or granddads would.

The film has a plot familiar from a lot of '50s science fiction: to name two extremes, it's basically the same situation as that underpinning The Day the Earth Stood Still and Plan 9 from Outer Space, only dealing threat from Earth's deepest oceans instead of Outer Space. Seems we humans have gotten big enough and advanced enough in our technology that the inhabitants of the advanced culture from the lost continent of Mu, far below the surface of the Pacific, have decided to launch an attack on the people of the surface before we have a weapon capable of resisting them. This results in something of a cloak-and-dagger first act in which several inexplicable destructive acts are interlaced with the attempts by a pair of photographers (Takashima Tadao and Fujiki Yu) and a detective (Koizumi Hiroshi) to figure out what's causing them, while someone claiming to be Agent #23 of Mu (Hirata Akihiko) attempts to kidnap retired Admiral Kosumi (Uehara Ken) and Jinguji Makoto (Fujiyama Yoko), daughter of a deceased captain who was a brilliant madman of sorts.

In short order, Captain Jinguji (Tazaki Jun) is revealed to be not dead at all, but hiding at a remote base where he has nearly finished building the undefeatable warship Atragon - the exact weapon that has scared Mu into speeding up its global domination plans. Kosumi and the governments of the world beg Jinguji to complete his great work and save them from Mu. Jinguji, a fierce nationalist who wants to use the ship only to restore Japan to prominence and glory in the wake of its humiliating defeat at the end of World War II, and it takes more than the entreaties of a long-lost daughter and former commanding officer to make him budge in the slightest. Which he of course does, because without Jinguji releasing the Atragon, there'd be no movie at all.

It's pulp nonsense - getting both pulpier and more nonsensical when the Atragon finally penetrates into the heart of the Mu Empire - though with a bite to it that couldn't really have come from any other country: I've given short shrift in my synopsis to just how much Atragon is concerned with the psychological ramifications of having lost such a major war in such a definitive way (in its Japanese version, at least; the American dub is purportedly almost identical, but I'd be shocked if there weren't some political overtones shifted). Exploring such concerns in genre plots had been bread and butter for director Honda Ishirō and producer Tanaka Tomoyuki going back to the blatantly symbolic Godzilla, but you still have to hand it to them, and screenwriter Sekizawa Shinichi, for leaving so much of that out in the open in a film with as much of a "wheee! the submarine has a frost gun AND it flies!" sensibility as Atragon. It's not the "point" of the film, but it's present to a completely unexpected degree.

Still, this is mostly a giddy old adventure, and for the most part, it's a terrifically well-made one; special effects director Tsuburaya Eiji was in particularly fine form overseeing the sea vessels and city-destroying shots in this movie, all the more impressive given an exceptionally cramped production schedule. The one major lapse is the giant sea monster Manda, inserted because the Toho executives doubted the viability of a film with absolutely no daikaiju in it (though Manda fits into the film far more comfortably than Maguma the walrus was wedged into the previous year's Gorath). It fits the general B-movie adventure notions of the film well enough - who doesn't like a sea serpent? But the design is ridiculous as hell: the creature boasts big cartoon eyes and a comical expression of mischievousness that looks more like a Legend of Zelda dungeon boss than a creature conceivably existing in the same world as Godzilla or Rodan.

Apart from Manda, though, there's hardly a missed stitch: Atragon is completely terrific, even in the dumbfounding flying scenes (which maybe work better because they are dumbfounding, and it's easy not to pay too much attention). And the less showy work is every bit as good: for the first time in any Toho tokusatsu, there are models of thing as quotidian as buses that look pretty great and are shot in a way that does not emphasis their size or their toylike qualities.

It's all great eye candy, and that's the thing the movie cares about the most. I do find that the twisty way the story is developed keeps it more interesting than a straightforward version of the plot could be, and it's great to see Tazaki rip into a larger role than he usually got. The dynamic between him and Fujiyama, a bent family relationship far weirder than the film's pulp elements require, is enough to keep the film interesting in between the effects scenes, though it's asking too much of Atragon to pretend that it's more than a fun adventure movie. The human stuff keeps it anchored and rational, but we're here for the submarine, the dragon, and the melodramatic undersea kingdom, and the film's pleasures are unmistakably shallow. Still, it's a lot more fun than a lot of very similar films from the same time can manage - the gorgeous effects has a lot to do with that - and I'm not ashamed in the least to say that I enjoyed every minute of the film. Nothing more than that, but for a 50-year-old movie, that's darned impressive. It's easy to see why this was such a big hit for Toho; it just plain works, silly pulp nonsense or no.

Categories: adventure, daikaiju eiga, japanese cinema, science fiction