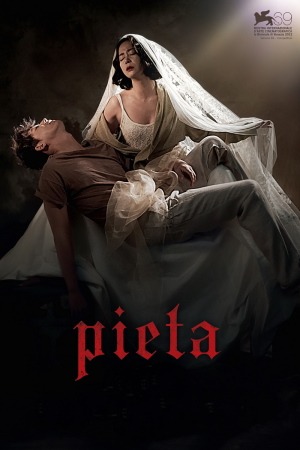

Mother and child reunion

Ever since it won the Golden Lion at the 2012 Venice Film Festival, Kim Ki-duk's Pieta has divided its audiences into "fucking brilliant!" or "fucking garbage!" camps just as harshly and brutally as its protagonist acts when he beats delinquent debtors into crippledom. And we now understand, at least in the abstract, where that sharp divide in the audience first comes from.

There's no way around it: this is an intensely violent, and frequently quite unpleasant film. I think that's something that defenders and detractors alike - and let's go ahead and clarify, I count myself a defender - have to agree on; the only difference opinion is not whether Pieta is a grueling experience, but whether that experience ends up building to something. I believe it does; Kim has worn a lot of hats in his directorial career, including that of provocateur, but for all its closely-observed nastiness, Pieta is about more than just human viciousness. The very title already tells us what the assumed point of the suffering is: transfiguration through sorrow. In other words, if the film doesn't grind us into a damp little smear to begin with, how can it ever give us the release of seeing the beauty of pity and forgiveness (and we should note that beyond the religious/artistic connotation, "pietà" is etymologically linked to "pity" - and to "piety", though that word doesn't obviously apply to this film)?

The figure so much in need of pity, both receiving it and giving it back to the world - is Kang-do (Lee Jung-lin), a thug in the employee of some loan sharks. His job consists of approaching those unable to pay off their debts with an offer: if you'll let me beat you until you become permanently crippled, I'll take the social assistance insurance you'll get for your newfound physical limitations, and we'll call it square. Sometimes he goes too far, and the victim ends up dead; sometimes he goes even farther, and the victim is alive in such a devastated emotional state that physical death would be a glossy bit of fun in comparison. It's one such man that we meet as the film opens: having lost the use of his legs, he wraps a chain around his neck in an industrial garage of some sort, he presses a button that begins winching the chain up, and it slowly pulls him from his wheelchair, strangling him with great deliberateness, though in a remarkable moment of restraint, Kim elects to focus on his feet during this process, and not his face. This moment is immediately followed with a context-free scene of Kang-do humping a pillow to orgasm in his solitary apartment, and while the film wins negative subtlety points for this one, it's at least true that this kind of one-two equivalence of hideous death and erotic excitement is the kind of thing you don't forget in a day or a week.

Into Kang-do's completely horrible but self-satisfied life - and not till after a good long sequence depicting in candid but not gore-hungry detail the sort of stuff he gets up to every day at work - comes Mi-sun (Jo Min-su), a middle-aged woman identifying herself as his mother, gone these thirty years since he was the tiniest scrap of a babe. This shakes things up for the mobster considerably; instead of the psychopathic cool be brings to all his jobs, he feels something that starts out looking like genuine, venomous rage for his mother. And this first truly explosive emotion triggers the shift that Mi-sun's steady, dogged presence will encourage throughout all the rest of the film: the development of empathy and guilt, and the realisation that he has destroyed so many lives over the years that atonement isn't even an applicable concept anymore.

Speaking entirely for myself, I find that the ends justify the means in this case, and that all the ickiness of the film is completely paid for by the delicacy with which Kang-do's inner journey (which is less hackneyed than a synopsis makes it sound) is carried out by the director and his two profoundly gifted actors, captured so frequently by Cho Yeong-jik's camera in icon-like close-ups. Maybe not all the ickiness. The big showcase scene of self-mutilation that has been central to so much debate can probably be justified if we take the film's forthright religious imagery at face value; it's not the grossest reference to transubstantiation ever filmed. But the incestuous clinches found elsewhere don't seem to serve much of a purpose that I can detect, besides making sure we're totally confused and creeped-out by Mi-sun. Arguably, the plot needs that to happen, but there are other, less garish ways of putting it across.

That being the case, just about everything else in the whole movie pretty much landed, as far as I'm concerned, sometimes with unexpected grace: there's a twist near the end that ought to trivialise the whole affair, and turn into nothing but a grim wallow in all the ways that cycles of violence destroy us all; instead, it's played in a way that turns into something much weirder and unreal, neatly inverting the mood that the entire film has established (prior to the ending, it's been so realist that it's downright grubby). It finds a register of spirituality that ends up making this long nasty slog uplifting, in its way: despite the complete absence of anything like a happy ending, it's an ending that suggests that we live in a moral universe where true atonement and contrition are recognised and appreciated. Not exactly the way to wrap up a crowd-pleaser, but in the context of the film, it works; I can absolutely see where the abrupt shift of registers from extreme violence to impressionistic religiosity could lose a viewer, and see even more why someone would have given up on the film long before that point. But to me, this is a film about finding a glimpse of hope and grace at the end of a long run of misery and evil, and I can't think of much that's more moving than that.

8/10

There's no way around it: this is an intensely violent, and frequently quite unpleasant film. I think that's something that defenders and detractors alike - and let's go ahead and clarify, I count myself a defender - have to agree on; the only difference opinion is not whether Pieta is a grueling experience, but whether that experience ends up building to something. I believe it does; Kim has worn a lot of hats in his directorial career, including that of provocateur, but for all its closely-observed nastiness, Pieta is about more than just human viciousness. The very title already tells us what the assumed point of the suffering is: transfiguration through sorrow. In other words, if the film doesn't grind us into a damp little smear to begin with, how can it ever give us the release of seeing the beauty of pity and forgiveness (and we should note that beyond the religious/artistic connotation, "pietà" is etymologically linked to "pity" - and to "piety", though that word doesn't obviously apply to this film)?

The figure so much in need of pity, both receiving it and giving it back to the world - is Kang-do (Lee Jung-lin), a thug in the employee of some loan sharks. His job consists of approaching those unable to pay off their debts with an offer: if you'll let me beat you until you become permanently crippled, I'll take the social assistance insurance you'll get for your newfound physical limitations, and we'll call it square. Sometimes he goes too far, and the victim ends up dead; sometimes he goes even farther, and the victim is alive in such a devastated emotional state that physical death would be a glossy bit of fun in comparison. It's one such man that we meet as the film opens: having lost the use of his legs, he wraps a chain around his neck in an industrial garage of some sort, he presses a button that begins winching the chain up, and it slowly pulls him from his wheelchair, strangling him with great deliberateness, though in a remarkable moment of restraint, Kim elects to focus on his feet during this process, and not his face. This moment is immediately followed with a context-free scene of Kang-do humping a pillow to orgasm in his solitary apartment, and while the film wins negative subtlety points for this one, it's at least true that this kind of one-two equivalence of hideous death and erotic excitement is the kind of thing you don't forget in a day or a week.

Into Kang-do's completely horrible but self-satisfied life - and not till after a good long sequence depicting in candid but not gore-hungry detail the sort of stuff he gets up to every day at work - comes Mi-sun (Jo Min-su), a middle-aged woman identifying herself as his mother, gone these thirty years since he was the tiniest scrap of a babe. This shakes things up for the mobster considerably; instead of the psychopathic cool be brings to all his jobs, he feels something that starts out looking like genuine, venomous rage for his mother. And this first truly explosive emotion triggers the shift that Mi-sun's steady, dogged presence will encourage throughout all the rest of the film: the development of empathy and guilt, and the realisation that he has destroyed so many lives over the years that atonement isn't even an applicable concept anymore.

Speaking entirely for myself, I find that the ends justify the means in this case, and that all the ickiness of the film is completely paid for by the delicacy with which Kang-do's inner journey (which is less hackneyed than a synopsis makes it sound) is carried out by the director and his two profoundly gifted actors, captured so frequently by Cho Yeong-jik's camera in icon-like close-ups. Maybe not all the ickiness. The big showcase scene of self-mutilation that has been central to so much debate can probably be justified if we take the film's forthright religious imagery at face value; it's not the grossest reference to transubstantiation ever filmed. But the incestuous clinches found elsewhere don't seem to serve much of a purpose that I can detect, besides making sure we're totally confused and creeped-out by Mi-sun. Arguably, the plot needs that to happen, but there are other, less garish ways of putting it across.

That being the case, just about everything else in the whole movie pretty much landed, as far as I'm concerned, sometimes with unexpected grace: there's a twist near the end that ought to trivialise the whole affair, and turn into nothing but a grim wallow in all the ways that cycles of violence destroy us all; instead, it's played in a way that turns into something much weirder and unreal, neatly inverting the mood that the entire film has established (prior to the ending, it's been so realist that it's downright grubby). It finds a register of spirituality that ends up making this long nasty slog uplifting, in its way: despite the complete absence of anything like a happy ending, it's an ending that suggests that we live in a moral universe where true atonement and contrition are recognised and appreciated. Not exactly the way to wrap up a crowd-pleaser, but in the context of the film, it works; I can absolutely see where the abrupt shift of registers from extreme violence to impressionistic religiosity could lose a viewer, and see even more why someone would have given up on the film long before that point. But to me, this is a film about finding a glimpse of hope and grace at the end of a long run of misery and evil, and I can't think of much that's more moving than that.

8/10