Faulk off

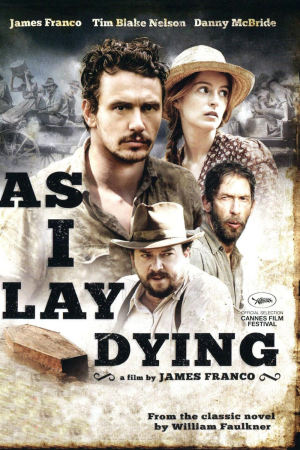

In the first place, there's absolutely no shame in failing to successfully adapt William Faulkner's 1930 novel As I Lay Dying into a cinematic form, as self-indulgent multi-hyphenate James Franco has so conspicuously failed to do. It is one of the most formally bookish books ever written, and while I think the word "unfilmable" really means that the person using that word is only admitting to their own lack of creativity and imagination, As I Lay Dying comes about as close to justifying that adjective as anything not written by James Joyce.

Franco, who is by absolutely no criterion a natural-born filmmaker, clearly didn't go about this idiotically, like some yahoo dilettantish actor who got enough fame and money to play-act at being a scholar and artist. It's obvious just from the evidence onsceen that he's been thinking long and hard about how to translate the film's compulsively literary prose to something that might carry off the same effect cinematically as Faulkner achieved in words. It doesn't end up doing that, mind you, but not out of laziness. More because Franco's two big ideas - split-screens and direct-address monologues - are applied somewhat arbitrarily and randomly, two words that do not apply in any measure to the exacting and precise novel.

At which point I should bow my head in the direction of those with no knowledge of the book, though I can't imagine that Franco intends this for such a crowd; and as far as that goes, I agree with him, considering as I do that As I Lay Dying is the best American novel of the 20th Century. It is a family story, set in Faulkner's mythic Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi, concerning a most grueling experience in the life of the Bundren family. It begins with matriarch Addie Bundren (Beth Grant), sick and about to die, expressing her will that her body should be buried in the town of Jefferson, some distance away; after she passes, her husband Anse (Tim Blake Nelson), and her five children set off to bring her body there in a homemade coffin built by eldest son Cash (Jim Parrack). A string of terrible events happen that blur the border between farce and cosmic tragedy beyond distinction.

To tell this story, and to explore the sprawling cast to whom it happens, Faulkner divided his 59 short chapters between 15 different first-person narrators, most frequently falling back on second son Darl (the largest role, which Franco graciously gave to himself), but also including a virtually incoherent and possibly mentally underdeveloped child, and the corpse of Addie Bundren herself, among several other vivid and distinctive voices. This, and not the corpse-carrying plot, is the most salient and characteristic element of As I Lay Dying in its literary form, and any attempt to film it must absolutely grapple with that structure.

The thing about the film Franco made is that it captures the letter of the book's subjectivity through the very odd method of splitting the frame in half with two different camera set-ups, while failing entirely to capture its spirit. Cinema is, by default, an objective medium, after all: put up the camera point it at a factory, record the people walking out of the factory without commentary. But that's by default, and it can be forced into subjectivity and perspective by a sufficiently gifted artist; this is the calling card of some of the greatest directors in the history of narrative filmmaking. As I Lay Dying, for all its experimental glee and the frequently beautiful images that result (the content in the two split screens frequently overlap in graphically appealing ways), isn't great filmmaking; at times it's barely even professional filmmaking, feeling more like Franco and a lot of his film set buddies got together to make a home movie in period costume. Which I imagine Franco to have in his possession already. It has the feel of a movie made with a lot of attention to form, but no real insight into what that form actually means, and it occupies a stubbornly third-person perspective that keeps us locked away from the characters even when they stare at the camera and talk to us.

None of which means that As I Lay Dying has to be bad, just that it's not a very good adaptation of Faulkner, but the ugly fact is that Franco's formal experimentation, however ineffective, is easily one of the film's triumphs. For all the energy that he and cinematographer Christina Voros sunk into figuring out which complementary angles to shoot the action from, and how to make the period setting look gorgeously picturesque on a budget, the director seems to have abandoned the actors entirely, unless it's just that no director now living would be able to coach 21st Century actors how to deliver Faulkner's thick, literary prose as though it were ever meant to be spoken as dialogue. At any rate, the acting, across the board, is comically bad; Nelson, who adopts a plummy accent that sounds a redneck version of the Swedish Chef, leaving only a handful of words legible from every sentence, is both the worst and the best - the worst in that he is inscrutable and hilarious in the wrong ways, and the best in that at least he's hilarious, and gives the film a liveliness it craves (not to mention that his outrageous, scenery-devouring accent is the only thing that remotely approaches the 15 different voices that Faulkner gave to his narrators. There are decent moments throughout, almost all of them involving silence: Ahna O'Reilly's defeated, empty body language as Dewey Dell, only daughter of the Bundrens, trying to pay for an abortion, Cash's increased disorientation as his broken leg begins to rot (I'd be reluctantly inclined to give Parrack best in show honors, but nobody hear deserves that kind of praise). There are far more moments that are out-and-out irritating and humiliating to watch.

So, while there might not be such a thing as an As I Lay Dying movie that works, this is clearly not the best or most well-thought out As I Lay Dying movie that could be made. It feels, overall, like what it is: a work of fan art made by a fan in a position to indulge himself with a paying audience. That somehow makes the whole thing more distasteful, but it doesn't take finding Franco an egocentric dilettante to find fault with his movie; the movie does a great job of that all on its own.

Franco, who is by absolutely no criterion a natural-born filmmaker, clearly didn't go about this idiotically, like some yahoo dilettantish actor who got enough fame and money to play-act at being a scholar and artist. It's obvious just from the evidence onsceen that he's been thinking long and hard about how to translate the film's compulsively literary prose to something that might carry off the same effect cinematically as Faulkner achieved in words. It doesn't end up doing that, mind you, but not out of laziness. More because Franco's two big ideas - split-screens and direct-address monologues - are applied somewhat arbitrarily and randomly, two words that do not apply in any measure to the exacting and precise novel.

At which point I should bow my head in the direction of those with no knowledge of the book, though I can't imagine that Franco intends this for such a crowd; and as far as that goes, I agree with him, considering as I do that As I Lay Dying is the best American novel of the 20th Century. It is a family story, set in Faulkner's mythic Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi, concerning a most grueling experience in the life of the Bundren family. It begins with matriarch Addie Bundren (Beth Grant), sick and about to die, expressing her will that her body should be buried in the town of Jefferson, some distance away; after she passes, her husband Anse (Tim Blake Nelson), and her five children set off to bring her body there in a homemade coffin built by eldest son Cash (Jim Parrack). A string of terrible events happen that blur the border between farce and cosmic tragedy beyond distinction.

To tell this story, and to explore the sprawling cast to whom it happens, Faulkner divided his 59 short chapters between 15 different first-person narrators, most frequently falling back on second son Darl (the largest role, which Franco graciously gave to himself), but also including a virtually incoherent and possibly mentally underdeveloped child, and the corpse of Addie Bundren herself, among several other vivid and distinctive voices. This, and not the corpse-carrying plot, is the most salient and characteristic element of As I Lay Dying in its literary form, and any attempt to film it must absolutely grapple with that structure.

The thing about the film Franco made is that it captures the letter of the book's subjectivity through the very odd method of splitting the frame in half with two different camera set-ups, while failing entirely to capture its spirit. Cinema is, by default, an objective medium, after all: put up the camera point it at a factory, record the people walking out of the factory without commentary. But that's by default, and it can be forced into subjectivity and perspective by a sufficiently gifted artist; this is the calling card of some of the greatest directors in the history of narrative filmmaking. As I Lay Dying, for all its experimental glee and the frequently beautiful images that result (the content in the two split screens frequently overlap in graphically appealing ways), isn't great filmmaking; at times it's barely even professional filmmaking, feeling more like Franco and a lot of his film set buddies got together to make a home movie in period costume. Which I imagine Franco to have in his possession already. It has the feel of a movie made with a lot of attention to form, but no real insight into what that form actually means, and it occupies a stubbornly third-person perspective that keeps us locked away from the characters even when they stare at the camera and talk to us.

None of which means that As I Lay Dying has to be bad, just that it's not a very good adaptation of Faulkner, but the ugly fact is that Franco's formal experimentation, however ineffective, is easily one of the film's triumphs. For all the energy that he and cinematographer Christina Voros sunk into figuring out which complementary angles to shoot the action from, and how to make the period setting look gorgeously picturesque on a budget, the director seems to have abandoned the actors entirely, unless it's just that no director now living would be able to coach 21st Century actors how to deliver Faulkner's thick, literary prose as though it were ever meant to be spoken as dialogue. At any rate, the acting, across the board, is comically bad; Nelson, who adopts a plummy accent that sounds a redneck version of the Swedish Chef, leaving only a handful of words legible from every sentence, is both the worst and the best - the worst in that he is inscrutable and hilarious in the wrong ways, and the best in that at least he's hilarious, and gives the film a liveliness it craves (not to mention that his outrageous, scenery-devouring accent is the only thing that remotely approaches the 15 different voices that Faulkner gave to his narrators. There are decent moments throughout, almost all of them involving silence: Ahna O'Reilly's defeated, empty body language as Dewey Dell, only daughter of the Bundrens, trying to pay for an abortion, Cash's increased disorientation as his broken leg begins to rot (I'd be reluctantly inclined to give Parrack best in show honors, but nobody hear deserves that kind of praise). There are far more moments that are out-and-out irritating and humiliating to watch.

So, while there might not be such a thing as an As I Lay Dying movie that works, this is clearly not the best or most well-thought out As I Lay Dying movie that could be made. It feels, overall, like what it is: a work of fan art made by a fan in a position to indulge himself with a paying audience. That somehow makes the whole thing more distasteful, but it doesn't take finding Franco an egocentric dilettante to find fault with his movie; the movie does a great job of that all on its own.