The 49th Chicago International Film Festival

Screens at CIFF: 10/12 & 10/14

World Premiere: 11 September, 2012, Dubai International Film Festival

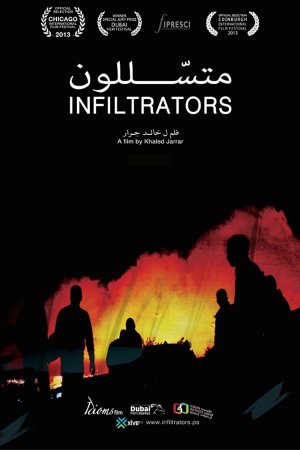

The first shots of Infiltrators end up having very little to do with the rest of the film, aesthetically at least, but they do make for an awfully compelling introduction to an awfully compelling documentary. Briefly, the opening introduces us to the bare fact of panicked running: just before dawn, there is noise, there are bodies moving and Khaled Jarrar's camera is jerking about violently, hardly able to keep up with the action at all. In fact, it can't keep up with the action; most of what we see is fragmentary and static, individuals frames holding for a half a second or longer, the whole thing skipping. The most immediately recognizable visual element of the whole are lights in the distance, rendered in the smudgy, low-fi digital camera and its grossly reduced framerate as jagged streaks of color floating in space. It is so abstract that it is, in the end, quite beautiful; poetry made out of shitty cinematography and hectic confusion.

As for what that running is all about: it turns out to be an attempt to smuggle people across the wall built by the Israeli government to keep the Palestinians in their place. Infiltrators, as we find after this in medias res opening turns into something a little bit more subdued, is about the difficult task of entering Jerusalem when one is Palestinian: difficult and dangerous when it's done illegally, and practically impossible to be done through the proper channels. The film is as broad an attempt can be made in a mere 70 minutes to cover all the angles of this subject from within the Palestinian community; Jarrar himself never enters, nor attempts to enter Jerusalem, instead holding back with the groups attempting to surreptitiously sneak around Israeli security officers at all hours of the night, and even a few times in broad daylight.

The subject matter, by itself, is interesting if not necessarily the freshest thing imaginable at this point: at any rate, the exact focus of the documentary is so specific and so limited in scope to the on-the-ground, moment-by-moment reality of the people trying to leave the carefully circumscribed space where they're meant to stay that it doesn't rehash the same arguments familiar from so many movies and documentaries about the occupation of Palestine. Jarrar's interviews reveal little details that I, at least, would never have really thought of; the frustrated impasse between human smugglers charging a healthy fee for the dangerous service they offer and the everyday people who want to see a decent doctor or the like, and who find those same fees to be the next thing to usury.

What's truly special about Infiltrators, though, is not the the situation being depicted, but the manner in which it is depicted. Jarrar's camera may not be very rugged and it certainly doesn't capture very high-quality footage, but the film's resolute lack of polish absolutely works to its benefit: above and beyond the usual tricks of cinéma vérité, handheld shakiness and significant graininess and overmixed ambient sound and such, things that contribute to a sense of perceived realism, Infiltrators looks and feels so unprofessional from its first shot onward, that one's eyes almost refuse to judge it to be a movie. It resembles home movies taken on the spur of the moment, archived and edited as a way of preserving the special in-the-moment perspective accidentally captured. I have absolutely no way of knowing whether this was how Jarrar happened to record these events; I strongly doubt so, given the number of interviews that populate the film. But the reality of how the film was made isn't as essential as the feeling the film has, and between the consumer-grade video and the obviously surreptitious way that many of the shots had to be filmed, that feeling is one of considerable grubby authenticity.

This ends up being, in fact, a film about how it was filmed as much as about the acts happening in front of the lens; not because there are any self-referential or autobiographical notes, but because the intimacy and flexibility of the camera end up being so inseparable from the events within the movie: if it's not quite the case that camera ends up feeling like a character, as in the similar (and mostly, more sophisticated and effective) 5 Broken Cameras, it nevertheless feels present in a way that even documentary cameras often do not. It is, yes, that whole "you are there" feeling, though I don't love that particular cliché, given added emphasis by the tangibility of the filmmaker in the same space as the people he shows us.

Realism isn't the only aesthetic idea that Jarrar has: some of the material is presented in a specifically non-real register, particularly a sequence where the sound cuts out completely, leaving us to watch Palestinians milling aimlessly through an Israeli border check as a pure visual experience; it's the most openly editorial moment in the film, forcing our attention to the images, which are those of petty control over weary people. Not that the film lacks an editorial point of view; without the director ever having to say it aloud, Infiltrators depicts the Palestinian people as desperate and frustrated, with every movement they make tense as fraught as in any thriller. And this also belies the impression that it is some kind of found-footage recording of events: Jarrar and editor Gaetan Harem have clearly shaped the material to make a point, it's just that the point is left for the viewer to stumble into, rather than be told by the autocratic filmmaker. But just because it's not overt doesn't make it subdued: this is a loud, angry yell of a movie, depicting a broken system with focused rage and refusing to pretend that this situation is anything but ineffective and intolerable.

8/10

World Premiere: 11 September, 2012, Dubai International Film Festival

The first shots of Infiltrators end up having very little to do with the rest of the film, aesthetically at least, but they do make for an awfully compelling introduction to an awfully compelling documentary. Briefly, the opening introduces us to the bare fact of panicked running: just before dawn, there is noise, there are bodies moving and Khaled Jarrar's camera is jerking about violently, hardly able to keep up with the action at all. In fact, it can't keep up with the action; most of what we see is fragmentary and static, individuals frames holding for a half a second or longer, the whole thing skipping. The most immediately recognizable visual element of the whole are lights in the distance, rendered in the smudgy, low-fi digital camera and its grossly reduced framerate as jagged streaks of color floating in space. It is so abstract that it is, in the end, quite beautiful; poetry made out of shitty cinematography and hectic confusion.

As for what that running is all about: it turns out to be an attempt to smuggle people across the wall built by the Israeli government to keep the Palestinians in their place. Infiltrators, as we find after this in medias res opening turns into something a little bit more subdued, is about the difficult task of entering Jerusalem when one is Palestinian: difficult and dangerous when it's done illegally, and practically impossible to be done through the proper channels. The film is as broad an attempt can be made in a mere 70 minutes to cover all the angles of this subject from within the Palestinian community; Jarrar himself never enters, nor attempts to enter Jerusalem, instead holding back with the groups attempting to surreptitiously sneak around Israeli security officers at all hours of the night, and even a few times in broad daylight.

The subject matter, by itself, is interesting if not necessarily the freshest thing imaginable at this point: at any rate, the exact focus of the documentary is so specific and so limited in scope to the on-the-ground, moment-by-moment reality of the people trying to leave the carefully circumscribed space where they're meant to stay that it doesn't rehash the same arguments familiar from so many movies and documentaries about the occupation of Palestine. Jarrar's interviews reveal little details that I, at least, would never have really thought of; the frustrated impasse between human smugglers charging a healthy fee for the dangerous service they offer and the everyday people who want to see a decent doctor or the like, and who find those same fees to be the next thing to usury.

What's truly special about Infiltrators, though, is not the the situation being depicted, but the manner in which it is depicted. Jarrar's camera may not be very rugged and it certainly doesn't capture very high-quality footage, but the film's resolute lack of polish absolutely works to its benefit: above and beyond the usual tricks of cinéma vérité, handheld shakiness and significant graininess and overmixed ambient sound and such, things that contribute to a sense of perceived realism, Infiltrators looks and feels so unprofessional from its first shot onward, that one's eyes almost refuse to judge it to be a movie. It resembles home movies taken on the spur of the moment, archived and edited as a way of preserving the special in-the-moment perspective accidentally captured. I have absolutely no way of knowing whether this was how Jarrar happened to record these events; I strongly doubt so, given the number of interviews that populate the film. But the reality of how the film was made isn't as essential as the feeling the film has, and between the consumer-grade video and the obviously surreptitious way that many of the shots had to be filmed, that feeling is one of considerable grubby authenticity.

This ends up being, in fact, a film about how it was filmed as much as about the acts happening in front of the lens; not because there are any self-referential or autobiographical notes, but because the intimacy and flexibility of the camera end up being so inseparable from the events within the movie: if it's not quite the case that camera ends up feeling like a character, as in the similar (and mostly, more sophisticated and effective) 5 Broken Cameras, it nevertheless feels present in a way that even documentary cameras often do not. It is, yes, that whole "you are there" feeling, though I don't love that particular cliché, given added emphasis by the tangibility of the filmmaker in the same space as the people he shows us.

Realism isn't the only aesthetic idea that Jarrar has: some of the material is presented in a specifically non-real register, particularly a sequence where the sound cuts out completely, leaving us to watch Palestinians milling aimlessly through an Israeli border check as a pure visual experience; it's the most openly editorial moment in the film, forcing our attention to the images, which are those of petty control over weary people. Not that the film lacks an editorial point of view; without the director ever having to say it aloud, Infiltrators depicts the Palestinian people as desperate and frustrated, with every movement they make tense as fraught as in any thriller. And this also belies the impression that it is some kind of found-footage recording of events: Jarrar and editor Gaetan Harem have clearly shaped the material to make a point, it's just that the point is left for the viewer to stumble into, rather than be told by the autocratic filmmaker. But just because it's not overt doesn't make it subdued: this is a loud, angry yell of a movie, depicting a broken system with focused rage and refusing to pretend that this situation is anything but ineffective and intolerable.

8/10