The 49th Chicago International Film Festival

Screens at CIFF: 10/17 & 10/18 & 10/19

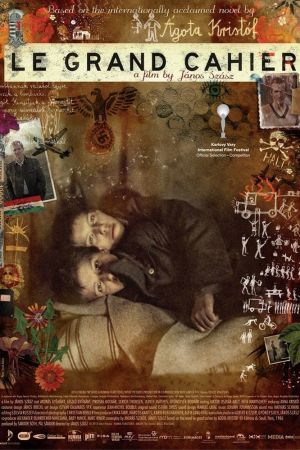

World premiere: 3 July, 2013, Karlovy Vary Film Festival

Special Mention by the Festival jury for Molnár Piroska

Szász János's The Notebook is an immensely handsome movie, and it is a movie about two children surviving World War II at the expense of their childlike innocence, and if you are anything like the film viewer that I am, this is the point where you begin backing away from the movie slow as you can, glancing surreptitiously to every side for something sharp to brandish, in case it decides to charge you. If that is the case, I am happy to say, Fear not this movie! For while it still suffers some of the normal extremes of its genre, including an obsession with seriousness and grimness that results in a nearly limitless cavalcade of agonies (the Nazi pedophile is the point where the movie will either break you or it won't), this is on the whole quite a lot more slippery than the dour prestige film it looks like. I can't quite get behind the intensity of the love that seems to have accrued to it in its young life (though the "kids + WWII" angle makes it obvious why this was Hungary's official submission for the Foreign Film Oscar), but it's quite a lot more interesting and special than the bare bones of its plot synopsis would indicate.

Part of that comes from its unabashed embrace of fairytale tropes, beginning with the way that virtually no characters have given names. Our protagonists are twin 13-year-olds, identified in the credits as only One (Gyémánt András) and Other (Gyémánt László) - their hair is slightly, recognisably different, and the boy I presume to be the One tends to be the first to speak or commit to actions, though it's a huge cornerstone of the movie that they do almost everything in near-perfect tandem - whose father (Matthes Ulrich) has been called up to war, leading their mother (Bognár Gyöngyvér) to take drastic steps to keep them out of harm's way. This means shipping them out to the deep country to live with her mother (Molnár Piroska), a hard-hearted sphere of a woman called "the witch" by the local townsfolk, despite the women having not spoken in 20 years. Perhaps as a result of this rift, perhaps out of her natural meanness of spirit, the boys' grandmother treats them with unflagging hostility, calling them "the bastards" and feeding them just enough to keep them from starving as she burdens them down with heavy labor.

Convinced by this, and by the general awfulness of the village, that life is a font of unstinting misery, the boys decided to train themselves how not to feel pain: taking turns beating each other to blunt the sting of physical brutality, and building a wall of cold hate that keeps them from feeling enough attachment to any human being other than themselves to feel emotional pain. Thus it is that they become the very avatars of a mechanistic, life-denying war, though The Notebook isn't so nihilistic as to make that the end point, and by the time the film reaches its end, the boys have been granted at least a very small measure of grace.

Ordinarily, I have very little patience for this kind of sorrow-glossed prestige filmmaking, which mistakes pain for profundity, but in the case of The Notebook, I can see my way clear to making an exception. For one thing, it exists in a stunningly unreal register - the glowing grey cinematography by Christian Berger gives the whole thing a remote, artistic quality above and beyond how much the story already feels like a fable more than a dramatic scenario, actively resisting any specific personalising elements for characters that it steadfastly renders as archetypes, even gross caricatures (it is both off-putting and miraculous how much the grandmother comes across as an elemental force). When there's a moment that foregrounds the actual meat and potatoes of Nazism - the deportation of a kindly Jewish shoemaker, alone among the villagers in being kind to the boys - it's weirdly dissonant, given how much the film to that point hasn't felt like it took place in an real-world historical context.

As a result of all this, the acting remains in a steadily presentational, stagey register that leaves the characters more like objects than people. It's hard to make that sound appealing (and impossible to use normal "good" and "bad" standards of acting to judge it, though I particularly liked Molnár, and Ulrich Thomsen as the gay Nazi with uncomfortably overstated affection for the boys' good looks), but Szász uses it to great advantage, leaving the film forced to be about primal feelings and gestures, since there is no space for anything more refined. I admire this in the film, though "admiration" is not by any means the most passionate emotion we can feel leaving a movie, especially ones about how young people deal with the horrors of the world. Still, however remote The Notebook ends up leaving itself, it has the effect of a good folktale, presenting raw, unvarnished emotional truths without any nuance or cleverness getting in the way. Bleak as it is, this is a kind of bedtime story in the end, and in that register it works quite well.

7/10

World premiere: 3 July, 2013, Karlovy Vary Film Festival

Special Mention by the Festival jury for Molnár Piroska

Szász János's The Notebook is an immensely handsome movie, and it is a movie about two children surviving World War II at the expense of their childlike innocence, and if you are anything like the film viewer that I am, this is the point where you begin backing away from the movie slow as you can, glancing surreptitiously to every side for something sharp to brandish, in case it decides to charge you. If that is the case, I am happy to say, Fear not this movie! For while it still suffers some of the normal extremes of its genre, including an obsession with seriousness and grimness that results in a nearly limitless cavalcade of agonies (the Nazi pedophile is the point where the movie will either break you or it won't), this is on the whole quite a lot more slippery than the dour prestige film it looks like. I can't quite get behind the intensity of the love that seems to have accrued to it in its young life (though the "kids + WWII" angle makes it obvious why this was Hungary's official submission for the Foreign Film Oscar), but it's quite a lot more interesting and special than the bare bones of its plot synopsis would indicate.

Part of that comes from its unabashed embrace of fairytale tropes, beginning with the way that virtually no characters have given names. Our protagonists are twin 13-year-olds, identified in the credits as only One (Gyémánt András) and Other (Gyémánt László) - their hair is slightly, recognisably different, and the boy I presume to be the One tends to be the first to speak or commit to actions, though it's a huge cornerstone of the movie that they do almost everything in near-perfect tandem - whose father (Matthes Ulrich) has been called up to war, leading their mother (Bognár Gyöngyvér) to take drastic steps to keep them out of harm's way. This means shipping them out to the deep country to live with her mother (Molnár Piroska), a hard-hearted sphere of a woman called "the witch" by the local townsfolk, despite the women having not spoken in 20 years. Perhaps as a result of this rift, perhaps out of her natural meanness of spirit, the boys' grandmother treats them with unflagging hostility, calling them "the bastards" and feeding them just enough to keep them from starving as she burdens them down with heavy labor.

Convinced by this, and by the general awfulness of the village, that life is a font of unstinting misery, the boys decided to train themselves how not to feel pain: taking turns beating each other to blunt the sting of physical brutality, and building a wall of cold hate that keeps them from feeling enough attachment to any human being other than themselves to feel emotional pain. Thus it is that they become the very avatars of a mechanistic, life-denying war, though The Notebook isn't so nihilistic as to make that the end point, and by the time the film reaches its end, the boys have been granted at least a very small measure of grace.

Ordinarily, I have very little patience for this kind of sorrow-glossed prestige filmmaking, which mistakes pain for profundity, but in the case of The Notebook, I can see my way clear to making an exception. For one thing, it exists in a stunningly unreal register - the glowing grey cinematography by Christian Berger gives the whole thing a remote, artistic quality above and beyond how much the story already feels like a fable more than a dramatic scenario, actively resisting any specific personalising elements for characters that it steadfastly renders as archetypes, even gross caricatures (it is both off-putting and miraculous how much the grandmother comes across as an elemental force). When there's a moment that foregrounds the actual meat and potatoes of Nazism - the deportation of a kindly Jewish shoemaker, alone among the villagers in being kind to the boys - it's weirdly dissonant, given how much the film to that point hasn't felt like it took place in an real-world historical context.

As a result of all this, the acting remains in a steadily presentational, stagey register that leaves the characters more like objects than people. It's hard to make that sound appealing (and impossible to use normal "good" and "bad" standards of acting to judge it, though I particularly liked Molnár, and Ulrich Thomsen as the gay Nazi with uncomfortably overstated affection for the boys' good looks), but Szász uses it to great advantage, leaving the film forced to be about primal feelings and gestures, since there is no space for anything more refined. I admire this in the film, though "admiration" is not by any means the most passionate emotion we can feel leaving a movie, especially ones about how young people deal with the horrors of the world. Still, however remote The Notebook ends up leaving itself, it has the effect of a good folktale, presenting raw, unvarnished emotional truths without any nuance or cleverness getting in the way. Bleak as it is, this is a kind of bedtime story in the end, and in that register it works quite well.

7/10