Blockbuster History: Concert films

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: the problem with concert documentaries, like One Direction: This Is Us, is that they're hardly worthy of that name "documentary", functioning mostly as just feature-length ads for the band in question, pitched to its established. There are not many exceptions - but they exist, and they are utterly glorious.

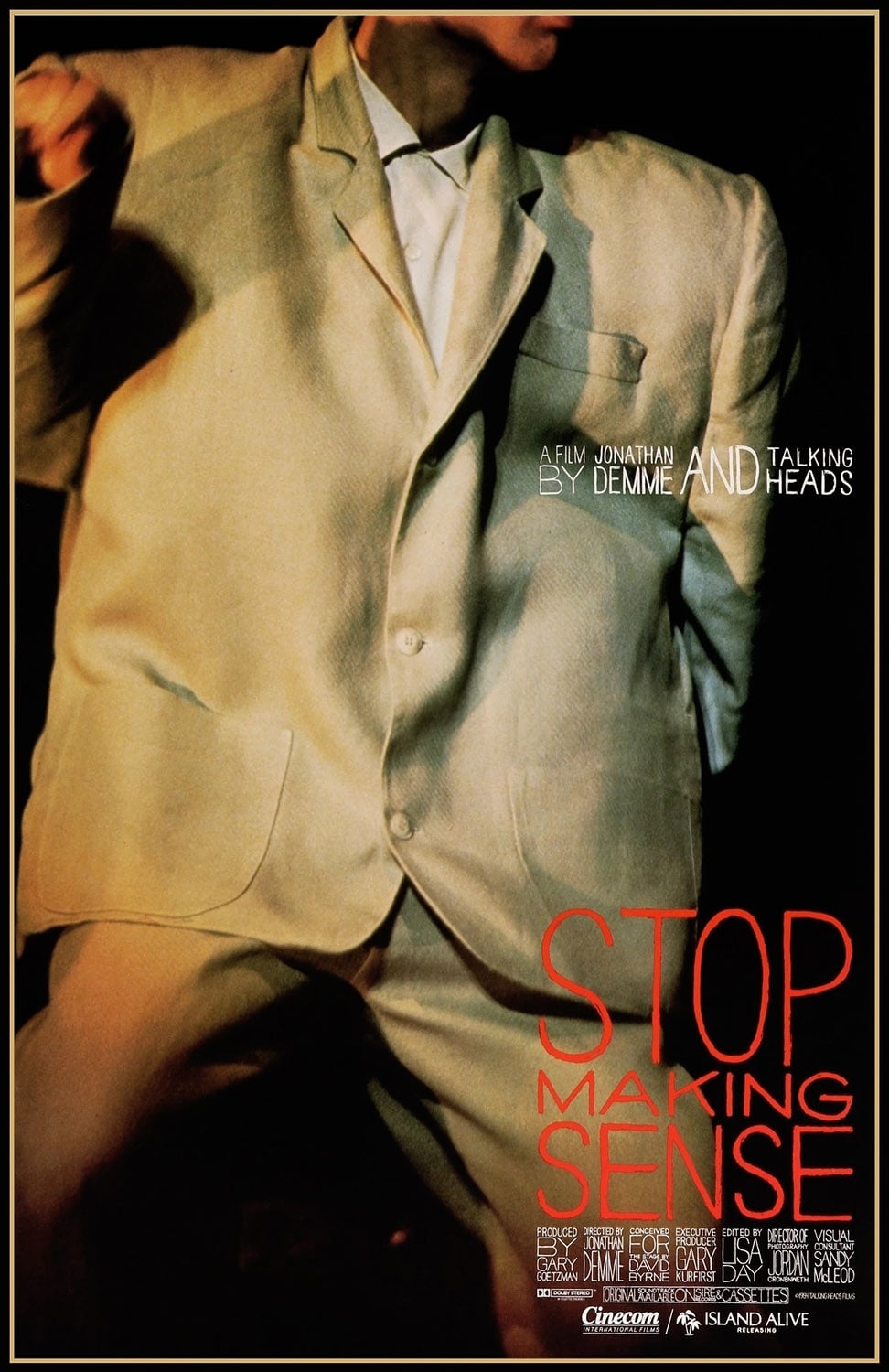

As far as I'm concerned, the eternally-burning question, "What is the best concert movie ever made?" has one of three possible answers, depending on what mode of concert movie you have in mind. The best "you are there" live footage, capturing a particular moment in time, the bands playing there, and the people listening and watching, is D.A. Pennebaker's 1968 Monterey Pop (a better film in every way than the thematically and cultural similar Woodstock); the best documentary about rock musicians on stage, going about the act of producing music, is Martin Scorsese's 1978 The Last Waltz; the best-constructed work of cinema that takes as its subject a concert is Jonathan Demme's 1984 Stop Making Sense, which also happens to be the only one of the three to focus on a single group (assuming we can allow that Tom Tom Club is simply a variant of the headlining Talking Heads, rather than a separate entity).

Full disclosure #1: I am an enthusiastic fan of Talking Heads. I get that any movie dominated by music is going to be limited for any viewer's personal attachment to that music, and somebody who flat-out hates Talking Heads - in an infinite universe, I have no doubt that such poor souls exist - probably wouldn't get anything out of a movie focusing entirely on their work, even one as beautifully made as I contend Stop Making Sense to be. That being said, full disclosure #2: I first became an enthusiastic fan of Talking Heads specifically because of this movie, having first seen it some half a decade ago, and I think that alone speaks well of how effectively the movie frames its subject, presenting the band with vigor and passion and generally being the most damned exciting thing to watch that you could imagine.

A lot of that is entirely due to the way that Demme, who conceived the film in close dialogue with Talking Heads frontman and artistic leader David Byrne, elected to shoot the film. It's quite miraculously simple: on three consecutive nights late in 1983, the Heads stopped over in Hollywood while on the tour to promote their fifth album, Speaking in Tongues, to perform three concerts. Demme shot each of these concerts: one from the left side, one from the right side, one to get a bunch of wide shots. Thus did the director and his spectacularly gifted cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth (of a little picture called Blade Runner) get to have something close to assurance that their squad of camera operators would be able to stay out of each other's paths, and in fact, in the final movie, prior to the last song, there's only something like four shots in which you can see another camera. This also meant that Demme and editor Lisa Day had an unbelievable wealth of footage to pick from, covering the whole show (which was effectively identical on each night) from about 20 angles, assuming that all seven operators were active on all three shows.

And these two things, taken in conjunction, mean that Stop Making Sense could be assembled with a relative freedom that virtually no other concert film I can name has ever enjoyed; and my but Demme took full advantage of this freedom. Befitting a band whose leading vision was so aggressively idiosyncratic, the film is full of shots and angles that seem impossibly deliberate and staged, for a genre typically filmed in a more fast-paced, intuitive way, and as the film progresses, it ceases to feel like the film is a recording of a Talking Heads concert, even a composite one. This isn't really a document of a concert; it is a film in which a concert takes place. Demme, in later years, has taken to calling this a "performance film", not a "concert film", which sounds pretentious and smug, except that it happens to be true: it's not trying to capture the immediacy and electricity of live music, but to depict a cinematic performance, and it's to the film's immeasurable benefit that the immediacy and electricity of playing live allowed that performance to be so energetic and pure.

At this point, we must nod our head in the direction of the main performer, David Byrne, who I suspect would tend to make any visual recording in which he was the main subject end up seeming mostly like performance art. Talking Heads lived on, meekly, after he left it, but it's not making any outlandish claims to say that he was the driving force behind all of its best and most memorable artistic achievements, often simply by flinging himself physically into the music with a daring and fearlessness most often associated with silent comedians. I cannot be more direct than this: Byrne is fucking fascinating to watch, moving in erratic jerky gestures, frequently behaving like his head is disarticulated from the rest of his body. The best example is also the movie's best sequence, set to maybe the band's most widely-known song, "Life During Wartime": Byrne wrenches back from the microphone in between breaths like it burns him, later on gliding his body around like a dancer performing a tribute to Siva. Before the song's end, he's flailing on the ground, spasming like he's in his death throes, drenched in sweat and singing in perfect harmony as he stares at the audience with an expressionless, alien face. Frequently, his whole body jolts like he's being given electric shocks right in the middle of the set.

If you're not familiar with the group, this undoubtedly sounds weird and horrifying; but as Cronenweth and Demme film it, using the Expressionist lighting scheme designed for the stage by Byrne himself, it's gripping stuff. The band's other most widely-known song, "Once in a Lifetime", is filmed mostly in one single take, with hard chiaroscuro lighting emphasisng every minute twist of flesh on Byrne's body as he moves fluidly from one gesticulation to another, and it's here above all that Stop Making Sense openly announces what it's doing, and why Demme likes to call it a performance movie: it is presenting Byrne and Talking Heads for us as visual objects, to be studied and examined, just simply to be looked at; a weird choice for a music film, when after all, listening is probably the thing we're most inclined to do. But Talking Heads is an unusually well-suited group to this kind of treatment, as Byrne's ideas were already so visually striking: the way the set and band seem to literally evolve over the course of the first four songs, the Fred Astaire references (a few moves in "Psycho Killer" come directly from Royal Wedding, and Byrne's dance with a lamp during "This Must Be the Place" recalls the coat rack scene from the same movie; there's an echo of the "Bojangles of Harlem" number from Swing Time in the shadows prominent throughout "Girlfriend Is Better"), the projection screens, and Byrne's iconic big grey suit, making a man who already seems out of place in his own body look even stranger, more detached, more lost.

The marriage of this imagery with the music was all Byrne; but the way that Demme and company craft it into a cinematic object is a piece of genius that Stop Making Sense possesses all its own. It is a gorgeous film, to begin with; the cutting not only pieces together disparate elements in a way that make you almost ignore the copious continuity errors, but raise the energy of the already pulsing music, and suck us right into the space occupied by the band (who are very frequently shown in close-ups far more snug than you'd ever expect to be). The sheer pleasure that the band takes in performing is readily visible as we watch them in close detail, and it starts to bleed off the screen. The last sequence, when Demme finally allows the live audience to emerge from the dimness, waking us up and giving us a place to identify with, and feel the rush that spectacting this weird event must have been like, is one of the greatest delayed releases I've experienced in a movie. All told, the random, nearly avant-garde imagery that the filmmakers and the band present us with ends up not making any sense, like the title promised, but it's all so precise even as it is totally loopy, and the music pressed up in our face so urgently and enticingly, that the movie is still as close to perfect as it gets.

As far as I'm concerned, the eternally-burning question, "What is the best concert movie ever made?" has one of three possible answers, depending on what mode of concert movie you have in mind. The best "you are there" live footage, capturing a particular moment in time, the bands playing there, and the people listening and watching, is D.A. Pennebaker's 1968 Monterey Pop (a better film in every way than the thematically and cultural similar Woodstock); the best documentary about rock musicians on stage, going about the act of producing music, is Martin Scorsese's 1978 The Last Waltz; the best-constructed work of cinema that takes as its subject a concert is Jonathan Demme's 1984 Stop Making Sense, which also happens to be the only one of the three to focus on a single group (assuming we can allow that Tom Tom Club is simply a variant of the headlining Talking Heads, rather than a separate entity).

Full disclosure #1: I am an enthusiastic fan of Talking Heads. I get that any movie dominated by music is going to be limited for any viewer's personal attachment to that music, and somebody who flat-out hates Talking Heads - in an infinite universe, I have no doubt that such poor souls exist - probably wouldn't get anything out of a movie focusing entirely on their work, even one as beautifully made as I contend Stop Making Sense to be. That being said, full disclosure #2: I first became an enthusiastic fan of Talking Heads specifically because of this movie, having first seen it some half a decade ago, and I think that alone speaks well of how effectively the movie frames its subject, presenting the band with vigor and passion and generally being the most damned exciting thing to watch that you could imagine.

A lot of that is entirely due to the way that Demme, who conceived the film in close dialogue with Talking Heads frontman and artistic leader David Byrne, elected to shoot the film. It's quite miraculously simple: on three consecutive nights late in 1983, the Heads stopped over in Hollywood while on the tour to promote their fifth album, Speaking in Tongues, to perform three concerts. Demme shot each of these concerts: one from the left side, one from the right side, one to get a bunch of wide shots. Thus did the director and his spectacularly gifted cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth (of a little picture called Blade Runner) get to have something close to assurance that their squad of camera operators would be able to stay out of each other's paths, and in fact, in the final movie, prior to the last song, there's only something like four shots in which you can see another camera. This also meant that Demme and editor Lisa Day had an unbelievable wealth of footage to pick from, covering the whole show (which was effectively identical on each night) from about 20 angles, assuming that all seven operators were active on all three shows.

And these two things, taken in conjunction, mean that Stop Making Sense could be assembled with a relative freedom that virtually no other concert film I can name has ever enjoyed; and my but Demme took full advantage of this freedom. Befitting a band whose leading vision was so aggressively idiosyncratic, the film is full of shots and angles that seem impossibly deliberate and staged, for a genre typically filmed in a more fast-paced, intuitive way, and as the film progresses, it ceases to feel like the film is a recording of a Talking Heads concert, even a composite one. This isn't really a document of a concert; it is a film in which a concert takes place. Demme, in later years, has taken to calling this a "performance film", not a "concert film", which sounds pretentious and smug, except that it happens to be true: it's not trying to capture the immediacy and electricity of live music, but to depict a cinematic performance, and it's to the film's immeasurable benefit that the immediacy and electricity of playing live allowed that performance to be so energetic and pure.

At this point, we must nod our head in the direction of the main performer, David Byrne, who I suspect would tend to make any visual recording in which he was the main subject end up seeming mostly like performance art. Talking Heads lived on, meekly, after he left it, but it's not making any outlandish claims to say that he was the driving force behind all of its best and most memorable artistic achievements, often simply by flinging himself physically into the music with a daring and fearlessness most often associated with silent comedians. I cannot be more direct than this: Byrne is fucking fascinating to watch, moving in erratic jerky gestures, frequently behaving like his head is disarticulated from the rest of his body. The best example is also the movie's best sequence, set to maybe the band's most widely-known song, "Life During Wartime": Byrne wrenches back from the microphone in between breaths like it burns him, later on gliding his body around like a dancer performing a tribute to Siva. Before the song's end, he's flailing on the ground, spasming like he's in his death throes, drenched in sweat and singing in perfect harmony as he stares at the audience with an expressionless, alien face. Frequently, his whole body jolts like he's being given electric shocks right in the middle of the set.

If you're not familiar with the group, this undoubtedly sounds weird and horrifying; but as Cronenweth and Demme film it, using the Expressionist lighting scheme designed for the stage by Byrne himself, it's gripping stuff. The band's other most widely-known song, "Once in a Lifetime", is filmed mostly in one single take, with hard chiaroscuro lighting emphasisng every minute twist of flesh on Byrne's body as he moves fluidly from one gesticulation to another, and it's here above all that Stop Making Sense openly announces what it's doing, and why Demme likes to call it a performance movie: it is presenting Byrne and Talking Heads for us as visual objects, to be studied and examined, just simply to be looked at; a weird choice for a music film, when after all, listening is probably the thing we're most inclined to do. But Talking Heads is an unusually well-suited group to this kind of treatment, as Byrne's ideas were already so visually striking: the way the set and band seem to literally evolve over the course of the first four songs, the Fred Astaire references (a few moves in "Psycho Killer" come directly from Royal Wedding, and Byrne's dance with a lamp during "This Must Be the Place" recalls the coat rack scene from the same movie; there's an echo of the "Bojangles of Harlem" number from Swing Time in the shadows prominent throughout "Girlfriend Is Better"), the projection screens, and Byrne's iconic big grey suit, making a man who already seems out of place in his own body look even stranger, more detached, more lost.

The marriage of this imagery with the music was all Byrne; but the way that Demme and company craft it into a cinematic object is a piece of genius that Stop Making Sense possesses all its own. It is a gorgeous film, to begin with; the cutting not only pieces together disparate elements in a way that make you almost ignore the copious continuity errors, but raise the energy of the already pulsing music, and suck us right into the space occupied by the band (who are very frequently shown in close-ups far more snug than you'd ever expect to be). The sheer pleasure that the band takes in performing is readily visible as we watch them in close detail, and it starts to bleed off the screen. The last sequence, when Demme finally allows the live audience to emerge from the dimness, waking us up and giving us a place to identify with, and feel the rush that spectacting this weird event must have been like, is one of the greatest delayed releases I've experienced in a movie. All told, the random, nearly avant-garde imagery that the filmmakers and the band present us with ends up not making any sense, like the title promised, but it's all so precise even as it is totally loopy, and the music pressed up in our face so urgently and enticingly, that the movie is still as close to perfect as it gets.

Categories: blockbuster history, concert films, documentaries, gorgeous cinematography, music