Menace to society

Fruitvale Station is a debut feature, and you don't ever lose sight of that fact. The good news is that it is an especially promising debut feature, and whatever it is that writer-director Ryan Coogler has in mind for his next project, it's something we should all be very excited about, particularly if it occupies the same aesthetic space as this picture, something so unadorned and observant of a particular way of living in a particular place for a particular stratum of humanity that it can't be referred to as anything other than "naturalism", though few and far between are the naturalist movies that have such interesting ideas about what to do with naturalism once you've gotten it; where a great many movies would take "this is a depiction of a culture virtually never seen in cinemas, and this is the behavior of an individual in that culture" as justification in itself, in Fruitvale Station, that is merely the opening gesture.

But still, as impressive and controlled and particularly aware of the impact that well-managed cinema can have is Coogler's debut, a debut it is, and not at all without flaws, of which the showiest is undoubtedly the trick of having all of the protagonist's text message conversations, and even just his phone contact list, superimposed over the action so we know exactly what he's saying and who he's calling. There is, arguably, merit to us knowing exactly what people are involved in his life (and then again, there arguably isn't: we surely don't need to see him dialing "Mom" right before a middle-aged woman picks up whom he immediately identifies as "Mom"), but the effect is like a zany intrusion of Scott Pilgrim vs. the World in the middle of a Dardenne brothers film, and while it peters off as the movie proceeds, I'd have given a lot for it to have not shown up at all.

Among the less glaring newbie missteps, there are the usual litany of flaws that tend to accrue to indie films as a class: there's a sameness to the visuals, leaning hard on medium close-ups spiced up with the occasional wide shot, the editing is mechanical and boring, making the movie feel a bit draggier than it really is, and the performances are immensely variable in quality, suggesting not just individual actors who don't have a good handle on their job (though that cannot be discounted), but that they also weren't being given especially purposeful direction. It's a problem mostly limited to the smaller characters, though the one major character bogged down by an aimless, one-note performance is very problematic indeed.

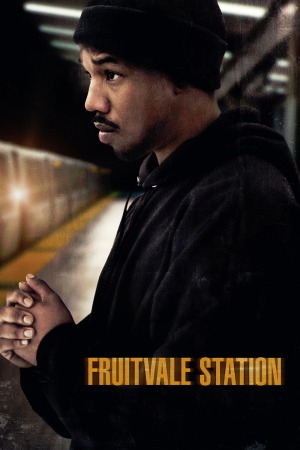

All of this being true, we're still left with an utterly moving and rich slice-of-life fable that admittedly gets a lot of its impact through borderline-exploitative means, though it's so vehemently sincere that calling it "exploitation" is patently untrue. It's based on a true story, the last day in the life of Oscar Grant III (Michael B. Jordan), a 22-year-old living in Oakland, California who was shot to death by policemen in the early hours of 1 January, 2009. Coogler does not hide his intentions in the least degree: this is a movie meant to show the depth and meaning of any human life, even one as far to the margins as Grants, and to condemn a social order in which the presumption that young black men should be assumed dangerous until proven otherwise has any kind of widespread acceptance (we can debate whether it's unacceptably crass and/or tasteless of the Weinstein Company to deliberately encourage comparisons between their movie and the Trayvon Martin shooting, but we cannot deny that it's massively fucked-up that either of those deaths happened).

The film presents Oscar as being basically a good kid who's made a fair number of mistakes and doesn't have quite the maturity level to back out of them gracefully, though he plainly wants to do good: leave behind a life of drugs and infidelity and fecklessness and be a good father to his young daughter, and to be faithful to his girlfriend Sophina (Melanie Diaz, whose performance I found grating as hell, and the biggest problem with the movie after the damn cell phone nonsense). But while it matters to Coogler's argument to present all of this, Fruitvale Station isn't really "about" Oscar's redemption, but about the texture of his life; he spends a day wandering around Oakland, chatting with people, trying to get back the job he frittered away, making plans for that evening. It's not a film driven to paint Oscar as a good soul who was martyred, but simply as a person doing person-like things; knowing that we're going into the film aware that this is a true story about a young black man who died, Coogler's intent is mostly to humanise this one story and take away the comforting "otherness" that happens when a story comes to us through the news media; one might be outraged by the death of Oscar Grant, or any young man who dies in similar circumstances, but it's apt to be in an abstract sense, divorced from humanity. Fruitvale Station restores that humanity. It takes the headline and the statistic (one more dead urban African-American) and demonstrates that behind this data point lived a person who had good points and flaws, and who surely didn't want or deserve to die.

To get to this point, Coogler first takes time to paint the details of Oscar's life with extreme precision: the buildings, the streets, the people; he also nurses out of Jordan one of the year's great performances thus far, a casual assemblage of half-articulate line deliveries and meaningful looks, nothing showy or impressive, but so immensely natural (that word again!) that the talented young actor (who has been somebody we all should have been paying attention to since the first season of The Wire, a decade ago, but at least he's finally breaking out with this part) seems to dissolve into the character without having to flag what he's doing so we notice the Great Acting. Insofar as Oscar is the prism through which the community and all the people in it, so unfamiliar to mainstream movie screens, is understood and given life, he is a truly great prism, and Jordan gives one of those performances that makes everybody around him seem better just by reflecting him.

It's a polemic, of course, not a very subtle one (there's a whole dead dog metaphor that's kind of embarrassing to watch), not at all points a well-advised one (the last sequence of the film, including footage of the real Oscar's daughter, is unbearably manipulative). But it hits hard, and while Coogler's artistry might need some evolving, his ability to wallop the viewer with emotion surely can't be improved upon. Full of love for the place it depicts with such intimacy, it's a movie suffused with passion and urgency, and those are things that trump "too many close-ups" and "wobbly performances" every day of the week.

But still, as impressive and controlled and particularly aware of the impact that well-managed cinema can have is Coogler's debut, a debut it is, and not at all without flaws, of which the showiest is undoubtedly the trick of having all of the protagonist's text message conversations, and even just his phone contact list, superimposed over the action so we know exactly what he's saying and who he's calling. There is, arguably, merit to us knowing exactly what people are involved in his life (and then again, there arguably isn't: we surely don't need to see him dialing "Mom" right before a middle-aged woman picks up whom he immediately identifies as "Mom"), but the effect is like a zany intrusion of Scott Pilgrim vs. the World in the middle of a Dardenne brothers film, and while it peters off as the movie proceeds, I'd have given a lot for it to have not shown up at all.

Among the less glaring newbie missteps, there are the usual litany of flaws that tend to accrue to indie films as a class: there's a sameness to the visuals, leaning hard on medium close-ups spiced up with the occasional wide shot, the editing is mechanical and boring, making the movie feel a bit draggier than it really is, and the performances are immensely variable in quality, suggesting not just individual actors who don't have a good handle on their job (though that cannot be discounted), but that they also weren't being given especially purposeful direction. It's a problem mostly limited to the smaller characters, though the one major character bogged down by an aimless, one-note performance is very problematic indeed.

All of this being true, we're still left with an utterly moving and rich slice-of-life fable that admittedly gets a lot of its impact through borderline-exploitative means, though it's so vehemently sincere that calling it "exploitation" is patently untrue. It's based on a true story, the last day in the life of Oscar Grant III (Michael B. Jordan), a 22-year-old living in Oakland, California who was shot to death by policemen in the early hours of 1 January, 2009. Coogler does not hide his intentions in the least degree: this is a movie meant to show the depth and meaning of any human life, even one as far to the margins as Grants, and to condemn a social order in which the presumption that young black men should be assumed dangerous until proven otherwise has any kind of widespread acceptance (we can debate whether it's unacceptably crass and/or tasteless of the Weinstein Company to deliberately encourage comparisons between their movie and the Trayvon Martin shooting, but we cannot deny that it's massively fucked-up that either of those deaths happened).

The film presents Oscar as being basically a good kid who's made a fair number of mistakes and doesn't have quite the maturity level to back out of them gracefully, though he plainly wants to do good: leave behind a life of drugs and infidelity and fecklessness and be a good father to his young daughter, and to be faithful to his girlfriend Sophina (Melanie Diaz, whose performance I found grating as hell, and the biggest problem with the movie after the damn cell phone nonsense). But while it matters to Coogler's argument to present all of this, Fruitvale Station isn't really "about" Oscar's redemption, but about the texture of his life; he spends a day wandering around Oakland, chatting with people, trying to get back the job he frittered away, making plans for that evening. It's not a film driven to paint Oscar as a good soul who was martyred, but simply as a person doing person-like things; knowing that we're going into the film aware that this is a true story about a young black man who died, Coogler's intent is mostly to humanise this one story and take away the comforting "otherness" that happens when a story comes to us through the news media; one might be outraged by the death of Oscar Grant, or any young man who dies in similar circumstances, but it's apt to be in an abstract sense, divorced from humanity. Fruitvale Station restores that humanity. It takes the headline and the statistic (one more dead urban African-American) and demonstrates that behind this data point lived a person who had good points and flaws, and who surely didn't want or deserve to die.

To get to this point, Coogler first takes time to paint the details of Oscar's life with extreme precision: the buildings, the streets, the people; he also nurses out of Jordan one of the year's great performances thus far, a casual assemblage of half-articulate line deliveries and meaningful looks, nothing showy or impressive, but so immensely natural (that word again!) that the talented young actor (who has been somebody we all should have been paying attention to since the first season of The Wire, a decade ago, but at least he's finally breaking out with this part) seems to dissolve into the character without having to flag what he's doing so we notice the Great Acting. Insofar as Oscar is the prism through which the community and all the people in it, so unfamiliar to mainstream movie screens, is understood and given life, he is a truly great prism, and Jordan gives one of those performances that makes everybody around him seem better just by reflecting him.

It's a polemic, of course, not a very subtle one (there's a whole dead dog metaphor that's kind of embarrassing to watch), not at all points a well-advised one (the last sequence of the film, including footage of the real Oscar's daughter, is unbearably manipulative). But it hits hard, and while Coogler's artistry might need some evolving, his ability to wallop the viewer with emotion surely can't be improved upon. Full of love for the place it depicts with such intimacy, it's a movie suffused with passion and urgency, and those are things that trump "too many close-ups" and "wobbly performances" every day of the week.