The films of Tony Scott

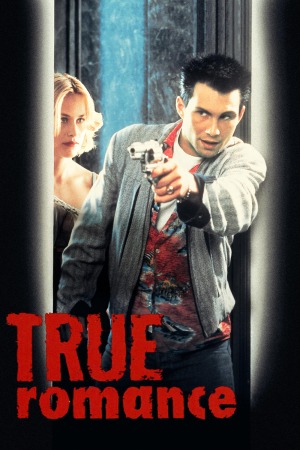

The organising principal which brings us to this point is a retrospective for director Tony Scott; but 1993's True Romance is special in being the child of two auteurs, and its historical reputation undoubtedly owes less to the man who directed it than the man who wrote it. For the film's script was by none other than future fanboy icon and iconic fanboy Quentin Tarantino, his first completed script, though the film did not come out until after he'd made his directorial debut with Reservoir Dogs. It's thus one of just three Tarantino screenplays that were directed by someone else, and even then, it enjoys a special privilege. For From Dusk Till Dawn was made by Tarantino's close associate Robert Rodriguez, and Tarantino was in the cast; while Natural Born Killers was changed so drastically by Oliver Stone and company as to be a fundamantally different film from the one Tarantino wrote. True Romance is, then, the one opportunity to see what a reasonably faithful intepretation of Tarantino's writing looks like when made entirely without any influence from Tarantino himself.

Now, True Romance is not "Tony Scott does a Quentin Tarantino movie", because it was 1993, and there wasn't enough data to say what "a Quentin Tarantino movie" even was. Instead, far more unexpectedly, True Romance is "Tony Scott does a Terrence Malick movie with Quentin Tarantino's script", a collision of names that absolutely should not be able to exist. But Tony Scott's Malick picture it is, and not in some accidental way, or anything like that. Scott was doing it on purpose, and he comes right out and tells us he's doing it on purpose in the second scene, which finds Patricia Arquette reciting voiceover narration in an airy, storybook register, while Hans Zimmer's score taps out a melody that can be best described as "the closest that you can get to the Orff music used in Badlands without actually running into copyright issues".

Badlands makes as much sense as any other cinematic touchstone, because it tells basically the same story as True Romance, and God knows how many other movies: boy and girl meet, fall in love, boy's casually amoral tendency towards crime puts the two lovers on the run. Like Badlands, and unlike most of the genre's highlights, True Romance isn't really about being on the run, though, for it's well over halfway through the movie that the central lovers have any inkling that they're being chased. Instead, it's a reverie, or an idyll if you will: pictorially and tonally ethereal, far more engaged by the emotional rhythms of two people intoxicated simply by each other's presence, than by the beats of the narrative. Of course, neither Scott nor Tarantino are interested by the same things as Malick, to put it mildly, so the form that this idyll takes is hugely different, involving a high-energy jaunt through Detroit and Los Angeles, and no so much a pacey amble through the unsettled landscapes of the American West.

Still, a romantic idyll it is, and in this at least we know that it's all Scott: Tarantino has observed in later years that the difference between the movie that he'd have directed and the movie Scott did direct was this tonal emphasis. It's the reason that Tarantino ended up forgiving Scott's insistence on adding a happy ending to the film, given that he ended up falling to much in love with the characters to include Tarantino's more badass-chic death-spattered finale. Certainly, True Romance is not remotely the film that Tarantino would have directed; it's frankly surprising that it's the movie directed by the man who gave the world Top Gun, outside of a POV roller coaster scene that stands out like a sore thumb in amongst all the dappled, painterly interiors and sun-kissed exteriors with which Scott and cinematographer Jeffrey L. Kimball mark this out as the gentlest and most visually romantic of all their collaborations (this the fourth and last). It's got its share of snazzy-cool moments, and overwrought violence (emphasised more in the one-minute-longer director's cut that's the easiest way to find the movie, though it's really nothing that you'd notice if you weren't hunting for it), and that ties it to the careers of both its prominent creators, for if they shared nothing else in common (and by and large, they do not), a love of Coolness is certainly something they both had in spades.

The lovers are Clarence Worley (Christian Slater), an Elvis enthusiast and comic book shop employee, introduced in the film's opening scene, it's most unapologetically Tarantino moment (a sprawling monologue about pop culture, with the punchline "I'd fuck Elvis"); and Alabama Whitman (Arquette), who meets cute with him at a Sonny Chiba marathon. It quickly turns out that she's a call girl, hired by his boss to give him a good time on his birthday, but she actually did fall in love on their charmingly geek-culture date with its culmination in hot sex, and barely any time later, they've gotten married, and he's gone on a bit of a murder spree against her former pimp, Drexl Spivey (Gary Oldman), stealing a huge pile of coke from him. This, in turn, puts Clarence and Alabama on the wrong side of very powerful gangsters, though their only thought at first is to scatter to California, partially to keep away from any eventual danger, but mostly to sell the drugs at and make a fortune.

Insofar as there's a plot, it proceeds exactly as you'd expect, but really, True Romance is a collection of hang-out scenes and cameos from a truly remarkable list of beloved character actors and future beloved character actors: Christopher Walken, Brad Pitt, Dennis Hopper, James Gandolfini, and Samuel L. Jackson are the biggest names to join Oldman in basically one- or two-scene performances, but they are not the only names. The focus of the film, though, is solely on Clarence and Alabama, and the odd situation they find themselves in; it's practically a screwball comedy, though Scott's handling of it is such that anything that isn't patently marked out as a laugh line in in the script doesn't come across as funny.

It's not a terribly great crime thriller; far too shaggy for that. Although my personal favorite scene is absolutely in that mode, in an absurdly digressive scene where the cops try to put a wire in Clarence's big drug deal with a movie executive (Saul Rubinek) that Scott intended as a genial piss-take of Joel Silver, producer of the director's personally painful The Last Boy Scout; it is both wholly comic (the most sustained funny part of the movie), and crackling well-assembled, though like everything in the movie, the editing is a touch on the frantic side. But it is a terribly fun wallow in trashiness and excess, without anything morally redemptive in the whole thing except for Alabama's soothing narration in the bookends. Between Tarantino's firecraker dialogue - this is when he still had something to prove - and Scott's glamorous, handsome mounting of the same (he's palpably happier to be directing this film than The Last Boy Scout), it's a sharp, snappy movie, thoroughly kinetic and sleek without drifting, as the director's films sometimes did, into glossy self-merchandising. Not every performance is equally great - Oldman is the unambiguous standout, as a genuinely terrifying monster, but then you have Tom Sizemore being completely uncertain what kind of movie he's in - and not every dialogic whirl is as smart and well-paced as pretty much every moment in Reservoir Dogs; the famous and beloved "Sicilian Scene" impresses me not at all, except insofar as it demonstrates that Tarantino's naughty schoolboy approach to using racial taboos was present at the very start of his career. The characters are almost all flat and stereotypical; but they're kind of meant to be, this is a road trip movie about two intoxicated lovers drifting through a Wonderland of low-life caricatures.

Frankly, the only thing that goes wrong with the movie is Slater, an unappealing actor in the best circumstances whom Scott had no handle on whatsoever; the best I can say about him is that he's pretty able at delivering even the most maddeningly stylised dialogue the script throws at him with aplomb. But he sucks a lot of the life out of the movie; with the director uncharacteristically deciding to make a movie about characters, not affect, it's a damn pity that the main character feels so oily, and Arquette's shockingly full and thoughtful performance of a retrograde stock character ends up somewhat wasted on a love story that never feels as legitimate as it could with a better performer. But as weird as it sounds, True Romance is at such a fever pitch in all other ways that the failure of its central character ends up being an irritation, but not a film-crippling problem. With a better actor, or at least a slightly more scaled-down performance, there's a version of True Romance that's Scott's best film and one of the finest morally nihilistic crime adventures of the '90s. Even in this state, it's quite a lot of fun, if vigorously shallow.

Now, True Romance is not "Tony Scott does a Quentin Tarantino movie", because it was 1993, and there wasn't enough data to say what "a Quentin Tarantino movie" even was. Instead, far more unexpectedly, True Romance is "Tony Scott does a Terrence Malick movie with Quentin Tarantino's script", a collision of names that absolutely should not be able to exist. But Tony Scott's Malick picture it is, and not in some accidental way, or anything like that. Scott was doing it on purpose, and he comes right out and tells us he's doing it on purpose in the second scene, which finds Patricia Arquette reciting voiceover narration in an airy, storybook register, while Hans Zimmer's score taps out a melody that can be best described as "the closest that you can get to the Orff music used in Badlands without actually running into copyright issues".

Badlands makes as much sense as any other cinematic touchstone, because it tells basically the same story as True Romance, and God knows how many other movies: boy and girl meet, fall in love, boy's casually amoral tendency towards crime puts the two lovers on the run. Like Badlands, and unlike most of the genre's highlights, True Romance isn't really about being on the run, though, for it's well over halfway through the movie that the central lovers have any inkling that they're being chased. Instead, it's a reverie, or an idyll if you will: pictorially and tonally ethereal, far more engaged by the emotional rhythms of two people intoxicated simply by each other's presence, than by the beats of the narrative. Of course, neither Scott nor Tarantino are interested by the same things as Malick, to put it mildly, so the form that this idyll takes is hugely different, involving a high-energy jaunt through Detroit and Los Angeles, and no so much a pacey amble through the unsettled landscapes of the American West.

Still, a romantic idyll it is, and in this at least we know that it's all Scott: Tarantino has observed in later years that the difference between the movie that he'd have directed and the movie Scott did direct was this tonal emphasis. It's the reason that Tarantino ended up forgiving Scott's insistence on adding a happy ending to the film, given that he ended up falling to much in love with the characters to include Tarantino's more badass-chic death-spattered finale. Certainly, True Romance is not remotely the film that Tarantino would have directed; it's frankly surprising that it's the movie directed by the man who gave the world Top Gun, outside of a POV roller coaster scene that stands out like a sore thumb in amongst all the dappled, painterly interiors and sun-kissed exteriors with which Scott and cinematographer Jeffrey L. Kimball mark this out as the gentlest and most visually romantic of all their collaborations (this the fourth and last). It's got its share of snazzy-cool moments, and overwrought violence (emphasised more in the one-minute-longer director's cut that's the easiest way to find the movie, though it's really nothing that you'd notice if you weren't hunting for it), and that ties it to the careers of both its prominent creators, for if they shared nothing else in common (and by and large, they do not), a love of Coolness is certainly something they both had in spades.

The lovers are Clarence Worley (Christian Slater), an Elvis enthusiast and comic book shop employee, introduced in the film's opening scene, it's most unapologetically Tarantino moment (a sprawling monologue about pop culture, with the punchline "I'd fuck Elvis"); and Alabama Whitman (Arquette), who meets cute with him at a Sonny Chiba marathon. It quickly turns out that she's a call girl, hired by his boss to give him a good time on his birthday, but she actually did fall in love on their charmingly geek-culture date with its culmination in hot sex, and barely any time later, they've gotten married, and he's gone on a bit of a murder spree against her former pimp, Drexl Spivey (Gary Oldman), stealing a huge pile of coke from him. This, in turn, puts Clarence and Alabama on the wrong side of very powerful gangsters, though their only thought at first is to scatter to California, partially to keep away from any eventual danger, but mostly to sell the drugs at and make a fortune.

Insofar as there's a plot, it proceeds exactly as you'd expect, but really, True Romance is a collection of hang-out scenes and cameos from a truly remarkable list of beloved character actors and future beloved character actors: Christopher Walken, Brad Pitt, Dennis Hopper, James Gandolfini, and Samuel L. Jackson are the biggest names to join Oldman in basically one- or two-scene performances, but they are not the only names. The focus of the film, though, is solely on Clarence and Alabama, and the odd situation they find themselves in; it's practically a screwball comedy, though Scott's handling of it is such that anything that isn't patently marked out as a laugh line in in the script doesn't come across as funny.

It's not a terribly great crime thriller; far too shaggy for that. Although my personal favorite scene is absolutely in that mode, in an absurdly digressive scene where the cops try to put a wire in Clarence's big drug deal with a movie executive (Saul Rubinek) that Scott intended as a genial piss-take of Joel Silver, producer of the director's personally painful The Last Boy Scout; it is both wholly comic (the most sustained funny part of the movie), and crackling well-assembled, though like everything in the movie, the editing is a touch on the frantic side. But it is a terribly fun wallow in trashiness and excess, without anything morally redemptive in the whole thing except for Alabama's soothing narration in the bookends. Between Tarantino's firecraker dialogue - this is when he still had something to prove - and Scott's glamorous, handsome mounting of the same (he's palpably happier to be directing this film than The Last Boy Scout), it's a sharp, snappy movie, thoroughly kinetic and sleek without drifting, as the director's films sometimes did, into glossy self-merchandising. Not every performance is equally great - Oldman is the unambiguous standout, as a genuinely terrifying monster, but then you have Tom Sizemore being completely uncertain what kind of movie he's in - and not every dialogic whirl is as smart and well-paced as pretty much every moment in Reservoir Dogs; the famous and beloved "Sicilian Scene" impresses me not at all, except insofar as it demonstrates that Tarantino's naughty schoolboy approach to using racial taboos was present at the very start of his career. The characters are almost all flat and stereotypical; but they're kind of meant to be, this is a road trip movie about two intoxicated lovers drifting through a Wonderland of low-life caricatures.

Frankly, the only thing that goes wrong with the movie is Slater, an unappealing actor in the best circumstances whom Scott had no handle on whatsoever; the best I can say about him is that he's pretty able at delivering even the most maddeningly stylised dialogue the script throws at him with aplomb. But he sucks a lot of the life out of the movie; with the director uncharacteristically deciding to make a movie about characters, not affect, it's a damn pity that the main character feels so oily, and Arquette's shockingly full and thoughtful performance of a retrograde stock character ends up somewhat wasted on a love story that never feels as legitimate as it could with a better performer. But as weird as it sounds, True Romance is at such a fever pitch in all other ways that the failure of its central character ends up being an irritation, but not a film-crippling problem. With a better actor, or at least a slightly more scaled-down performance, there's a version of True Romance that's Scott's best film and one of the finest morally nihilistic crime adventures of the '90s. Even in this state, it's quite a lot of fun, if vigorously shallow.