The Films of Tony Scott

NB: At this point in this retrospective, I should be turning to the 1986 film Top Gun, but I have already reviewed it, and have nothing substantial to add to what I said at that time.

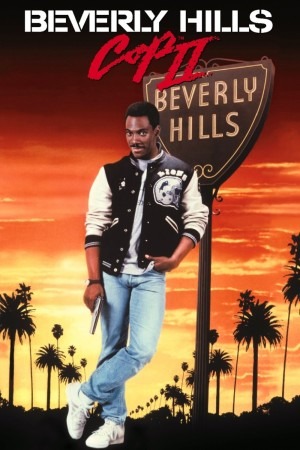

The 1980s were a sequel-mad decade nearly on par with the present day, so it is no surprise at all that the action-comedy Beverly Hills Cop, the highest-grossing film of 1984 (for there were also some ways in which the '80s were very different) should end up with a sequel. And while Beverly Hills Cop II didn't explode the Zeitgeist like its predecessor did, it still managed to end up the third-highest-grossing film of 1987, behind only Three Men and a Baby and Fatal Attraction (for there where also some ways in which the '80s were fucking unrecognisable).

Better yet, BHC II is, as sequels go, not a terribly pointless one. Beverly Hills Cop is already not a cinematic masterpiece without peer or precedent, serving mostly as an excuse to watch Eddie Murphy doing what he does (that is to say; what he did, back in the mid-'80s when his career was fresh and he hadn't spent so many years making unforgivably pandering family movies that he'd become incapable of doing anything else), being sassy, foul-mouthed, and just assertive enough about being a black man that he could score some points, without necessarily making anybody uncomfortable about that. BHC II is basically, the same thing, though compared the first movie, it skews a bit more heavily to comedy than to action, which is not to its benefit as a narrative, or a character drama or anything, really, except a delivery system for Murphy. But Murphy in those days was appealing enough that this proves to be very nearly sufficient.

Indeed, the fact that Murphy himself helped to shape the story helps cement the impression that this film is not terribly invested in its own criminal narrative, but in being a star vehicle, and it's that subtle shift away from BHC the first that still marks the sequel out as, well, a sequel, and one from an age when making a sequel was more about giving a fresh coat of paint to the same situations than expanding the first film's narrative universe, so it's not exactly like BHC II was ever going to be in a position to tell a story of unnatural richness and fascination.

The story is, anyway, that in Beverly Hills, California - helpfully identified by onscreen titles twice, in case we were still buying popcorn the first time, or something - police officers Andrew Bogomil (Ronny Cox), Billy Rosewood (Judge Reinhold), and John Taggart (John Ashton) are all working on the case of the Alphabet Criminal, a series of robberies named for their obnoxious "hey cops, betcha can't find me" clue-filled letters. Already, we find out what kind of movie this intends to be when Bogomil, Rosewood, and Taggart are introduced, and presented throughout the film, really, as people we already know and love, which was probably a lot more fair in '87 than it is now; God bless it, but Beverly Hills Cop hasn't maintained the full flush of its cachet over more than a quarter of a century. And besides, I don't suppose anybody really did give a shit about any of them: the real point of interest is of course Murphy's Axel Foley, a Detroit detective working undercover to crack a fake credit card ring.

The Alphabet case goes bad, and Bogomil ends up in the hospital, with Rosewood and Taggart bumped down to traffic duty, and when Foley sees this on the news (because the non-fatal injury of a Southern California policeman would plainly be of vital interest to the Detroit media market), he immediately pulls some of his quick-talking magic to skip off to Beverly Hills, to avenge his friend Bogomil and complete that man's mission to crack the case. It is also assumed that we know who Foley is and how he came to be so close to the Beverly Hills PD; but at a certain point, you have to accept that if you're watching a movie with II in the title, you better have done the appropriate research.

But anyway, it's not like the series' mythology is so dense and nuanced that there's any real chance of missing out on what's happening. The film serves one purpose: to put Axel Foley in positions where he can launch into con-man patter to trick somebody into helping him, or confuse the villains into messing up. Even Axel Foley himself matters only as a vessel for the actor playing him; there's nothing about the character separate from Murphy that's terribly memorable or interesting.

None of this is a flaw, exactly: the movie entirely succeeds at its singularly modest goals. It's not, at any turn, as good as the earlier film, and maybe that is a flaw: the jokes are busier but less clever, the plot is less focused and when Axel cracks the case, there's so little reason to care what the case has actually been, given how blandly convoluted it is and how run-of the-mill its antagonist (even with the ever-colorful Jürgen Prochnow playing him). The film is so focused on delivering what it thinks we want in the form of its central character, that it never builds up any stakes or context for him to seem as savvy as cop as he did in the first film. Though all things being equal, I'd rather have such a sequel err on the side of not enough plot than do like Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest and try to paper over its shallowness with a really big, sprawling, messy plot.

Anyway, we are gathered here today not to hash out the merits of a generation-old action comedy that's remarkably light on action and boasts less comedy than it might, but to note its importance in the career of director Tony Scott. And this is something that's honestly a bit hard to do. Scott was picked for the job by producers Don Simpson & Jerry Bruckheimer based on the massive success of their previous collaboration together, Top Gun, which was the director's second feature and one that largely anticipates everything that would later become distinctively his; it is shiny, it is immensely loud, it is captivated by men working with machines, it is unabashedly militaristic. BHC II is absolutely none of these things; in fact, it's only real point of aesthetic interest at all is that it is assembled to an unusual degree out of individual shots that feel weirdly isolated within scenes, rather than based in traditional continuity. When this character or that is in close-up, that close-up often as not feels like it's severing them from the rest of the movie; there is a gap between locations and the actions that take place there. It's an interestingly materialistic way of shooting a movie of this sort, almost ironic in a way, but it ends up providing little other than an interesting thing to notice, and it anyway is not really characteristic of Scott as a director at all. Even the cinematography, by Top Gun DP Jeffrey Kimball, lacks that film's TV commercial sexiness about staging events to look particularly sleek and glamorous.

The whole thing, really, seems to work largely on the level of, "do pretty much what you did before", with none of the actors pushing very hard, and the Harold Faltermeyer score largely reiterating the iconic theme music from the first movie in marginally different orchestrations. If the point of all this, from the director's point of view, was to prove that he could be a good, obedient hack, doing right by a franchise he came into late, then it worked, I guess; but that never pays off elsewhere in his career, and love him or hate him, the one thing you absolutely can't say of Tony Scott is that he was ever been much for anonymous hackwork.

The 1980s were a sequel-mad decade nearly on par with the present day, so it is no surprise at all that the action-comedy Beverly Hills Cop, the highest-grossing film of 1984 (for there were also some ways in which the '80s were very different) should end up with a sequel. And while Beverly Hills Cop II didn't explode the Zeitgeist like its predecessor did, it still managed to end up the third-highest-grossing film of 1987, behind only Three Men and a Baby and Fatal Attraction (for there where also some ways in which the '80s were fucking unrecognisable).

Better yet, BHC II is, as sequels go, not a terribly pointless one. Beverly Hills Cop is already not a cinematic masterpiece without peer or precedent, serving mostly as an excuse to watch Eddie Murphy doing what he does (that is to say; what he did, back in the mid-'80s when his career was fresh and he hadn't spent so many years making unforgivably pandering family movies that he'd become incapable of doing anything else), being sassy, foul-mouthed, and just assertive enough about being a black man that he could score some points, without necessarily making anybody uncomfortable about that. BHC II is basically, the same thing, though compared the first movie, it skews a bit more heavily to comedy than to action, which is not to its benefit as a narrative, or a character drama or anything, really, except a delivery system for Murphy. But Murphy in those days was appealing enough that this proves to be very nearly sufficient.

Indeed, the fact that Murphy himself helped to shape the story helps cement the impression that this film is not terribly invested in its own criminal narrative, but in being a star vehicle, and it's that subtle shift away from BHC the first that still marks the sequel out as, well, a sequel, and one from an age when making a sequel was more about giving a fresh coat of paint to the same situations than expanding the first film's narrative universe, so it's not exactly like BHC II was ever going to be in a position to tell a story of unnatural richness and fascination.

The story is, anyway, that in Beverly Hills, California - helpfully identified by onscreen titles twice, in case we were still buying popcorn the first time, or something - police officers Andrew Bogomil (Ronny Cox), Billy Rosewood (Judge Reinhold), and John Taggart (John Ashton) are all working on the case of the Alphabet Criminal, a series of robberies named for their obnoxious "hey cops, betcha can't find me" clue-filled letters. Already, we find out what kind of movie this intends to be when Bogomil, Rosewood, and Taggart are introduced, and presented throughout the film, really, as people we already know and love, which was probably a lot more fair in '87 than it is now; God bless it, but Beverly Hills Cop hasn't maintained the full flush of its cachet over more than a quarter of a century. And besides, I don't suppose anybody really did give a shit about any of them: the real point of interest is of course Murphy's Axel Foley, a Detroit detective working undercover to crack a fake credit card ring.

The Alphabet case goes bad, and Bogomil ends up in the hospital, with Rosewood and Taggart bumped down to traffic duty, and when Foley sees this on the news (because the non-fatal injury of a Southern California policeman would plainly be of vital interest to the Detroit media market), he immediately pulls some of his quick-talking magic to skip off to Beverly Hills, to avenge his friend Bogomil and complete that man's mission to crack the case. It is also assumed that we know who Foley is and how he came to be so close to the Beverly Hills PD; but at a certain point, you have to accept that if you're watching a movie with II in the title, you better have done the appropriate research.

But anyway, it's not like the series' mythology is so dense and nuanced that there's any real chance of missing out on what's happening. The film serves one purpose: to put Axel Foley in positions where he can launch into con-man patter to trick somebody into helping him, or confuse the villains into messing up. Even Axel Foley himself matters only as a vessel for the actor playing him; there's nothing about the character separate from Murphy that's terribly memorable or interesting.

None of this is a flaw, exactly: the movie entirely succeeds at its singularly modest goals. It's not, at any turn, as good as the earlier film, and maybe that is a flaw: the jokes are busier but less clever, the plot is less focused and when Axel cracks the case, there's so little reason to care what the case has actually been, given how blandly convoluted it is and how run-of the-mill its antagonist (even with the ever-colorful Jürgen Prochnow playing him). The film is so focused on delivering what it thinks we want in the form of its central character, that it never builds up any stakes or context for him to seem as savvy as cop as he did in the first film. Though all things being equal, I'd rather have such a sequel err on the side of not enough plot than do like Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest and try to paper over its shallowness with a really big, sprawling, messy plot.

Anyway, we are gathered here today not to hash out the merits of a generation-old action comedy that's remarkably light on action and boasts less comedy than it might, but to note its importance in the career of director Tony Scott. And this is something that's honestly a bit hard to do. Scott was picked for the job by producers Don Simpson & Jerry Bruckheimer based on the massive success of their previous collaboration together, Top Gun, which was the director's second feature and one that largely anticipates everything that would later become distinctively his; it is shiny, it is immensely loud, it is captivated by men working with machines, it is unabashedly militaristic. BHC II is absolutely none of these things; in fact, it's only real point of aesthetic interest at all is that it is assembled to an unusual degree out of individual shots that feel weirdly isolated within scenes, rather than based in traditional continuity. When this character or that is in close-up, that close-up often as not feels like it's severing them from the rest of the movie; there is a gap between locations and the actions that take place there. It's an interestingly materialistic way of shooting a movie of this sort, almost ironic in a way, but it ends up providing little other than an interesting thing to notice, and it anyway is not really characteristic of Scott as a director at all. Even the cinematography, by Top Gun DP Jeffrey Kimball, lacks that film's TV commercial sexiness about staging events to look particularly sleek and glamorous.

The whole thing, really, seems to work largely on the level of, "do pretty much what you did before", with none of the actors pushing very hard, and the Harold Faltermeyer score largely reiterating the iconic theme music from the first movie in marginally different orchestrations. If the point of all this, from the director's point of view, was to prove that he could be a good, obedient hack, doing right by a franchise he came into late, then it worked, I guess; but that never pays off elsewhere in his career, and love him or hate him, the one thing you absolutely can't say of Tony Scott is that he was ever been much for anonymous hackwork.

Categories: action, comedies, summer movies, tony scott, worthy sequels