Year of Blood: All is calm, all is fright

Christmas! The bloodiest, most vicious holiday of them all! Or at least that is what the preponderance of yuletide horror pictures would have you believe. Clearly, I cannot let such an important day for death and destruction go by with just a single review, and thus I no a launch a full week with the one and only Christmas slasher franchise! You better watch out...

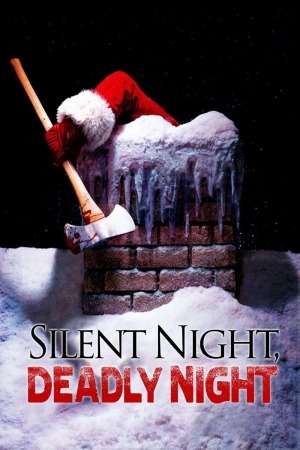

9 October, 1984, is perhaps the definitive single date in the entire history of the American slasher film. Two movies opened on that date that represent two entirely different phases of the '80s slasher boom, one striking a brand new way forward and one summing up everything that had gone so deeply wrong. The former was Wes Craven's A Nightmare on Elm Street, the movie that found you could add a paranormal element to the already stale slasher template and squeeze a few more years out of the subgenre that had apparently been tottering around on its last legs (that Nightmare is also one of the very best slasher films ever made certainly helped). The latter was Silent Night, Deadly Night, which plays as something like a parody of the form, a checklist of all the least imaginative elements of an unimaginative genre: a setting linked to a particular calendar date, a killer who pointedly rotates through a cycle of various edged weapons, the better to increase the variety of deaths, a psychologically dubious "sexual neurotic" explanation for why the killer was so anxious to do his killing, and related to that, a whole mess of naked breasts: it is, verily, one of the breastiest slasher movies I can think of that doesn't tip right over into exploitation.

Most significantly, it is also just about the highest-profile victim of the growing social furor over slasher films in the United States; in the days of Reagan and widespread cultural conservatism, there was a genuine hatred of violent horror cinema in the '80s simply unlike anything else the English-speaking world has witnessed in the years since: religious leaders were seeing Satanic cults behind every marginally dark film or song that came out, newspapers in the States, Great Britain, and Australia were eager to blame every act of youth violence on messages gleaned from a metal band or Jason Voorhees. And along came poor, dumb Silent Night, Deadly Night, with an ad campaign entirely predicated on one thing only: this is the movie where Santa Claus kills people.

Comfortably ensconced in our modern world where Santa's Slay can be released and turn into a reasonably well-known cult movie without single pair of panties becoming even modestly bunched, this sounds like a frankly ridiculous response. But SNDN was at the center of a massive controversy: protests outside the theaters where it was playing, petitions were circulated, the most powerful movie critics in America, Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert, publicly shamed the filmmakers on their television show. The film was disappeared from theaters after just two weeks, and released a couple of years later in a heavily bowdlerised version; the full, unexpurgated version of the movie wouldn't come out until even later still. It's important to stress that there's nothing about the film that is particularly heinous, in and of itself; only the fact that it depicts a man in a Santa costume killing people, which had been done before (minimally, the 1980 duo of To All a Goodnight and Christmas Evil/You Better Watch Out do the exact same thing), and which is significantly not the same thing as Santa himself killing people caused this controversy over a film that, heightened boob count or no, is not meaningfully darker or more violent than any other slasher from that year or the four years preceding it. But the pressure had been building ever since Friday the 13th sashayed into the culture in 1980, and it had to let off somewhere. "Killer Santa" was a convenient valve at the right time.

I'd dearly love it if I could be all righteously umbraged about this, and decry a world that would senselessly, and with great reactionary fervor, pillory such an innocuous movie in the public square. And certainly, that's a shitty thing to happen, and it speak ill of American society - though not as ill as the Nasties speak of Britain, so I'll always have that - but the unfortunate truth is that SNDN is a pretty wobbly patch of earth in which to plant one's flag. It's not that it's, like BAD bad, for a slasher movie, and if nothing else, the screenplay by Michael Hickey is rather a great deal stronger than a '84 horror picture could possibly be expected to have. It nonetheless suffers from its share of flaws and then some: a mostly limp cast, and unabashedly poor gore effects for one thing, and a whole lot of padding, between a slow-moving first half, and a back half just crammed right full of extraneous scenes. I will say on its behalf that director Charles E. Sellier, Jr. does find a way to put a bit more tension in it than many slashers have managed, and padded or not, it's still just 85 minutes in its uncut state, and while those minutes don't skip by like an innocent child on a spring day, it's not hardly a slog.

So, here's the condensed version of what happens: on 24 December, 1971, five-year-old Billy (Jonathan Best) watches his parents get killed by a robber dressed as Santa Claus - he first shoots Billy's father, in the driver's seat of a car, and then pulls Billy's mother out to rape her before cutting her throat. In the 1974 Christmas season, Billy (now Danny Wagner), living in a Catholic orphanage, is instructed in the ways of punishment and shame by a merciless Mother Superior (Lilyan Chauvin), and shown to have incredibly deep-seated feelings of horror about Christmas and Santa, whom he views to a retributive figure, not a kindly one. Finally, in 1984, Billy (Robert Brian Wilson) is placed in a job by kindly Sister Margaret (Gilmer McCormick), working at a toy store, and this first happens in the springtime; but the year does click around, and no matter how well Billy does the rest of the year, when Christmas and the in-store Santa come around, he starts to lose his shit; things come to a head on Christmas Eve, when he's obliged to stand-in as the man in the big red suit, and if that hadn't already pushed him right up to the edge, the alcohol forced on him by a garrulous boss - Billy being a Good Boy who doesn't drink - would do the job, and he takes his co-workers' jokes about being Santa a bit too literally in his heightened state; coupled with his belief that Santa's job is to kill the naughty, you have the ingredients for a fairly bloody spree before dawn on Christmas morning though the victims tend towards the usual slasher fare of the promiscuous or just dickish, with not a single dead child in the entire movie.

Yes, that was the "condensed" version - the full version would have made it much clearer just how much of the film has gone by before we meet 18-year-old Billy, and how much energy the movie spends developing his character as a fragile psyche with an outrageous fear of Santa Claus. And here we see where good screenwriting and good filmmaking don't have to necessarily be in the same place. In storytelling and structural terms, the opening third of SNDN is sort of astonishing: the audience grows up with Billy, if you will, and we get to watch as his psychological state is created, rather than have a pre-existing psychology explained to us. You don't see many psycho killer movies lay out that development as thoughtfully or deliberately as happens here; it's not just a shocking scene of a little boy watching a murderous Santa, but a full-on short film that teases out that boy's feelings and terrors.

The crippling flaw is that this requires that SNDN have not one, but two awfully good child actors to play the younger versions of Billy, and child actors are not, as a class, super-reliable; the really great ones, moreover, being particularly unlikely to end up in a killer Santa slasher movie. And so, during all this time we're meant to be getting to know Billy, we're actually just getting to know that Danny Wagner isn't up to playing Young Norman Bates with anything like the complexity we need if the remainder of the film is going to land. When we finally land in 1984, then, we're given virtually nothing more than "this is what Billy looks like now" before a montage takes us right to 23 December, and Wilson, who is not such a great actor himself, but largely capable of playing a semi-nuanced movie psycho when he's got to, doesn't have much of a chance to do any character building himself, since the script assumes that has already happened - relies on it, in fact.

When a psychologically-oriented crazy killer movie bumble its psychology this bad, there's not much you can do with it.

There are merits along the way: Sellier's directing trades on our knowledge of existing slasher tropes to up the tension in a way that, however functional and lazy, works - the 1971 sequence in particular, where we know damn good and well that little Billy will have to see something dreadful happen with that murderous Santa on the loose, because it's that kind of movie, is all the more nerve-wracking because we don't know when that intersection will come. Shitty '80s horror icon and nudity specialist Linnea Quigley puts in a very small role as one of the victims, and demonstrates why she, among all the disposable hot girls in all the genre films of the decade, developed such a following as she got bigger, better parts later on: there's a genuine spark of movie star charisma happening with everything she does, and though you could never, ever declare her to be a great, or even a good actress, she's so much more comfortable with the camera than anyone else, and has such a sardonic spark, it's impossible not to be taken with her. In a generally weak cast, Chauvin's brittle Mother Superior is a wonderfully harsh, glaring standout.

And, of course, if Killer Santa movies didn't work on a primordial level, they wouldn't exist.

But the good bits have to fight against a lot of badness: countless scenes that don't matter to anything else in the whole movie (e.g. comic bumbling cops breaking into the wrong house, a scene that contributes not a damn thing to the rest of the plot), or don't pay off in any meaningful way (early on, Billy is the only one who can speak with his catatonic, Santa-hating grandfather, but this doesn't end up indicating anything that makes any actual, logical sense); the death scenes, with one single sled-based exception, are quite squeamish and restrained, lacking any of the forcefulness that would give the film some kind of heft. Worst of all, maybe, is that while Billy is a complex anti-hero, something you practically never see in a slasher film, Wilson simply does not have what it takes to sell even the version of Billy in the script, let alone deepen him any more.

On balance, SNDN is at least one of the better slasher films made in the States in the mid-'80s, though the degree to which that's an actual compliment is debatable. Certainly, it starts with a better foundation than most, and its ambition is faultless, though no movie good enough to pay off the particular form that ambition took was ever going to be produced in this genre. The talent and money and time just weren't there. A noble failure, let's call it, and that alone is high praise: how many slasher films can be even briefly considered a noble anything?

(Useless closing thought: the toy store where Billy works is a ridiculous cornucopia of copyright-hedging brand names and childhood ephemera, with a Jabba the Hutt playset getting considerable screentime. I am reminded of my absolute favorite thing about cheap genre films: with no budget for set design, they are obliged to offer an almost documentary-like window on the world of their creation).

Body Count: 13, a fair number for a slasher film in this decadent stage of the genre's development; though Billy himself only commits eight of those, mostly bunched into a massive 15-minute whirlwind of death.

Reviews in this series

Silent Night, Deadly Night (Sellier, 1984)

Silent Night, Deadly Night, Part 2 (Harry, 1987)

Silent Night, Deadly Night III: Better Watch Out! (Hellman, 1989)

Silent Night, Deadly Night 4: Initiation (Yuzna, 1990)

Silent Night, Deadly Night 5: The Toy Maker (Kitrosser, 1991)

9 October, 1984, is perhaps the definitive single date in the entire history of the American slasher film. Two movies opened on that date that represent two entirely different phases of the '80s slasher boom, one striking a brand new way forward and one summing up everything that had gone so deeply wrong. The former was Wes Craven's A Nightmare on Elm Street, the movie that found you could add a paranormal element to the already stale slasher template and squeeze a few more years out of the subgenre that had apparently been tottering around on its last legs (that Nightmare is also one of the very best slasher films ever made certainly helped). The latter was Silent Night, Deadly Night, which plays as something like a parody of the form, a checklist of all the least imaginative elements of an unimaginative genre: a setting linked to a particular calendar date, a killer who pointedly rotates through a cycle of various edged weapons, the better to increase the variety of deaths, a psychologically dubious "sexual neurotic" explanation for why the killer was so anxious to do his killing, and related to that, a whole mess of naked breasts: it is, verily, one of the breastiest slasher movies I can think of that doesn't tip right over into exploitation.

Most significantly, it is also just about the highest-profile victim of the growing social furor over slasher films in the United States; in the days of Reagan and widespread cultural conservatism, there was a genuine hatred of violent horror cinema in the '80s simply unlike anything else the English-speaking world has witnessed in the years since: religious leaders were seeing Satanic cults behind every marginally dark film or song that came out, newspapers in the States, Great Britain, and Australia were eager to blame every act of youth violence on messages gleaned from a metal band or Jason Voorhees. And along came poor, dumb Silent Night, Deadly Night, with an ad campaign entirely predicated on one thing only: this is the movie where Santa Claus kills people.

Comfortably ensconced in our modern world where Santa's Slay can be released and turn into a reasonably well-known cult movie without single pair of panties becoming even modestly bunched, this sounds like a frankly ridiculous response. But SNDN was at the center of a massive controversy: protests outside the theaters where it was playing, petitions were circulated, the most powerful movie critics in America, Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert, publicly shamed the filmmakers on their television show. The film was disappeared from theaters after just two weeks, and released a couple of years later in a heavily bowdlerised version; the full, unexpurgated version of the movie wouldn't come out until even later still. It's important to stress that there's nothing about the film that is particularly heinous, in and of itself; only the fact that it depicts a man in a Santa costume killing people, which had been done before (minimally, the 1980 duo of To All a Goodnight and Christmas Evil/You Better Watch Out do the exact same thing), and which is significantly not the same thing as Santa himself killing people caused this controversy over a film that, heightened boob count or no, is not meaningfully darker or more violent than any other slasher from that year or the four years preceding it. But the pressure had been building ever since Friday the 13th sashayed into the culture in 1980, and it had to let off somewhere. "Killer Santa" was a convenient valve at the right time.

I'd dearly love it if I could be all righteously umbraged about this, and decry a world that would senselessly, and with great reactionary fervor, pillory such an innocuous movie in the public square. And certainly, that's a shitty thing to happen, and it speak ill of American society - though not as ill as the Nasties speak of Britain, so I'll always have that - but the unfortunate truth is that SNDN is a pretty wobbly patch of earth in which to plant one's flag. It's not that it's, like BAD bad, for a slasher movie, and if nothing else, the screenplay by Michael Hickey is rather a great deal stronger than a '84 horror picture could possibly be expected to have. It nonetheless suffers from its share of flaws and then some: a mostly limp cast, and unabashedly poor gore effects for one thing, and a whole lot of padding, between a slow-moving first half, and a back half just crammed right full of extraneous scenes. I will say on its behalf that director Charles E. Sellier, Jr. does find a way to put a bit more tension in it than many slashers have managed, and padded or not, it's still just 85 minutes in its uncut state, and while those minutes don't skip by like an innocent child on a spring day, it's not hardly a slog.

So, here's the condensed version of what happens: on 24 December, 1971, five-year-old Billy (Jonathan Best) watches his parents get killed by a robber dressed as Santa Claus - he first shoots Billy's father, in the driver's seat of a car, and then pulls Billy's mother out to rape her before cutting her throat. In the 1974 Christmas season, Billy (now Danny Wagner), living in a Catholic orphanage, is instructed in the ways of punishment and shame by a merciless Mother Superior (Lilyan Chauvin), and shown to have incredibly deep-seated feelings of horror about Christmas and Santa, whom he views to a retributive figure, not a kindly one. Finally, in 1984, Billy (Robert Brian Wilson) is placed in a job by kindly Sister Margaret (Gilmer McCormick), working at a toy store, and this first happens in the springtime; but the year does click around, and no matter how well Billy does the rest of the year, when Christmas and the in-store Santa come around, he starts to lose his shit; things come to a head on Christmas Eve, when he's obliged to stand-in as the man in the big red suit, and if that hadn't already pushed him right up to the edge, the alcohol forced on him by a garrulous boss - Billy being a Good Boy who doesn't drink - would do the job, and he takes his co-workers' jokes about being Santa a bit too literally in his heightened state; coupled with his belief that Santa's job is to kill the naughty, you have the ingredients for a fairly bloody spree before dawn on Christmas morning though the victims tend towards the usual slasher fare of the promiscuous or just dickish, with not a single dead child in the entire movie.

Yes, that was the "condensed" version - the full version would have made it much clearer just how much of the film has gone by before we meet 18-year-old Billy, and how much energy the movie spends developing his character as a fragile psyche with an outrageous fear of Santa Claus. And here we see where good screenwriting and good filmmaking don't have to necessarily be in the same place. In storytelling and structural terms, the opening third of SNDN is sort of astonishing: the audience grows up with Billy, if you will, and we get to watch as his psychological state is created, rather than have a pre-existing psychology explained to us. You don't see many psycho killer movies lay out that development as thoughtfully or deliberately as happens here; it's not just a shocking scene of a little boy watching a murderous Santa, but a full-on short film that teases out that boy's feelings and terrors.

The crippling flaw is that this requires that SNDN have not one, but two awfully good child actors to play the younger versions of Billy, and child actors are not, as a class, super-reliable; the really great ones, moreover, being particularly unlikely to end up in a killer Santa slasher movie. And so, during all this time we're meant to be getting to know Billy, we're actually just getting to know that Danny Wagner isn't up to playing Young Norman Bates with anything like the complexity we need if the remainder of the film is going to land. When we finally land in 1984, then, we're given virtually nothing more than "this is what Billy looks like now" before a montage takes us right to 23 December, and Wilson, who is not such a great actor himself, but largely capable of playing a semi-nuanced movie psycho when he's got to, doesn't have much of a chance to do any character building himself, since the script assumes that has already happened - relies on it, in fact.

When a psychologically-oriented crazy killer movie bumble its psychology this bad, there's not much you can do with it.

There are merits along the way: Sellier's directing trades on our knowledge of existing slasher tropes to up the tension in a way that, however functional and lazy, works - the 1971 sequence in particular, where we know damn good and well that little Billy will have to see something dreadful happen with that murderous Santa on the loose, because it's that kind of movie, is all the more nerve-wracking because we don't know when that intersection will come. Shitty '80s horror icon and nudity specialist Linnea Quigley puts in a very small role as one of the victims, and demonstrates why she, among all the disposable hot girls in all the genre films of the decade, developed such a following as she got bigger, better parts later on: there's a genuine spark of movie star charisma happening with everything she does, and though you could never, ever declare her to be a great, or even a good actress, she's so much more comfortable with the camera than anyone else, and has such a sardonic spark, it's impossible not to be taken with her. In a generally weak cast, Chauvin's brittle Mother Superior is a wonderfully harsh, glaring standout.

And, of course, if Killer Santa movies didn't work on a primordial level, they wouldn't exist.

But the good bits have to fight against a lot of badness: countless scenes that don't matter to anything else in the whole movie (e.g. comic bumbling cops breaking into the wrong house, a scene that contributes not a damn thing to the rest of the plot), or don't pay off in any meaningful way (early on, Billy is the only one who can speak with his catatonic, Santa-hating grandfather, but this doesn't end up indicating anything that makes any actual, logical sense); the death scenes, with one single sled-based exception, are quite squeamish and restrained, lacking any of the forcefulness that would give the film some kind of heft. Worst of all, maybe, is that while Billy is a complex anti-hero, something you practically never see in a slasher film, Wilson simply does not have what it takes to sell even the version of Billy in the script, let alone deepen him any more.

On balance, SNDN is at least one of the better slasher films made in the States in the mid-'80s, though the degree to which that's an actual compliment is debatable. Certainly, it starts with a better foundation than most, and its ambition is faultless, though no movie good enough to pay off the particular form that ambition took was ever going to be produced in this genre. The talent and money and time just weren't there. A noble failure, let's call it, and that alone is high praise: how many slasher films can be even briefly considered a noble anything?

(Useless closing thought: the toy store where Billy works is a ridiculous cornucopia of copyright-hedging brand names and childhood ephemera, with a Jabba the Hutt playset getting considerable screentime. I am reminded of my absolute favorite thing about cheap genre films: with no budget for set design, they are obliged to offer an almost documentary-like window on the world of their creation).

Body Count: 13, a fair number for a slasher film in this decadent stage of the genre's development; though Billy himself only commits eight of those, mostly bunched into a massive 15-minute whirlwind of death.

Reviews in this series

Silent Night, Deadly Night (Sellier, 1984)

Silent Night, Deadly Night, Part 2 (Harry, 1987)

Silent Night, Deadly Night III: Better Watch Out! (Hellman, 1989)

Silent Night, Deadly Night 4: Initiation (Yuzna, 1990)

Silent Night, Deadly Night 5: The Toy Maker (Kitrosser, 1991)

Categories: horror, slashers, tis the season, year of blood