Health care crisis

"Plague! We are in the middle of a fucking plague! And you behave like this! Plague! Forty million infected people is a fucking plague! We are in the worst shape we have ever, ever, ever been in. All those pills we’re shoveling down our throats, forget it! ACT UP has been taken over by a lunatic fringe that can’t get together, nobody agrees with anything, all we can do is field a couple of hundred people at a demonstration. That’s not going to make anybody pay attention! Not until we get millions out there! And we can’t do that! All we can do is pick at each other, and yell at each other. And I say to you in year ten, the same thing I said to you in 1981, when there were 41 cases: until we get our acts together, all of us, we are as good as dead."

-ACT UP co-founder Larry Kramer, 1991

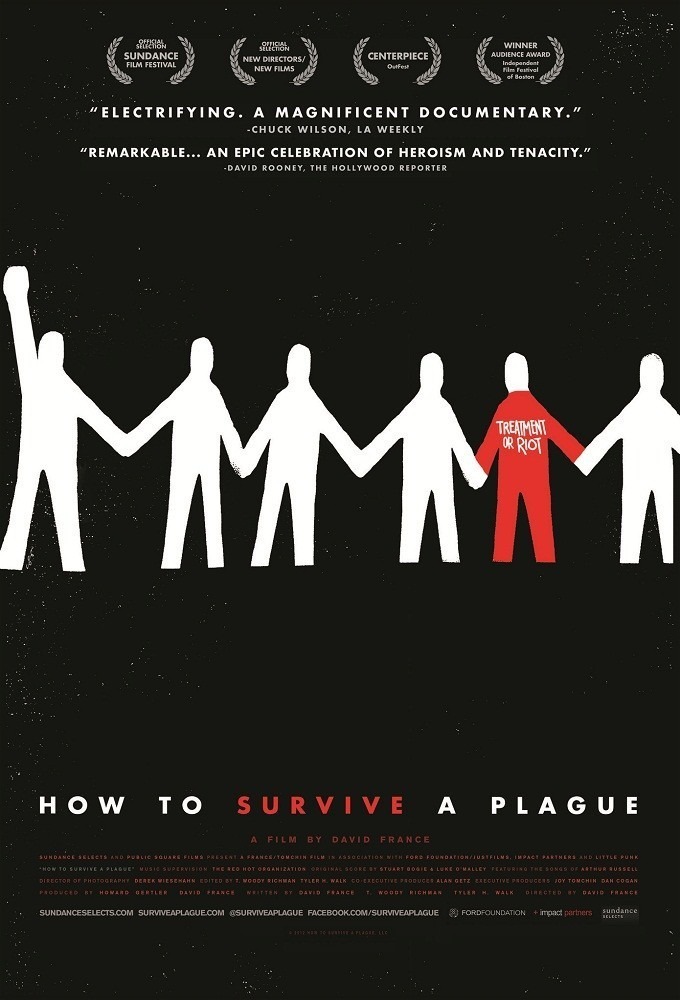

There are, it seems to me, three distinct, all very meaningful ways in which How to Survive a Plague triumphs: as a remarkably vivid and moving and detailed documentary of how New York's gay community lived with and fought against the AIDS pandemic from the late-1980s to the mid-1990s; as an exhilarating and then depressing and then exhilarating again study of how protest groups can change the world even as they give into the usual liberal sin of back-biting and arbitrary ideological purity tests; and as a an unusually nuanced, cinematically sophisticated documentary that actually finds a way to be an intelligent and admirable work of art in addition to its more overt sociological implications. As I am a goddamn terrible human being, I expect it will surprise none of my regular readers that I liked the last reason the best.

The film is the directorial debut of David France, an investigative reporter; and it shows. The investigative report bit, not the directorial debut bit. In fact, How to Survive a Plague is a freakishly self-assured first movie, clear and objective and scrupulous even as it's passionate and heartbreaking; it's every inch the kind of documentary that people who love documentaries a lot get to point to as a reason why. It gets there, in large part, because of France's journalistic scrupulousness, as I was saying: the film plunges the viewer right back into the horrid days of 1987, when in-depth scientific knowledge of HIV and AIDS were starting to come into some kind of shape, and American society at large was just starting to absorb that fact that it wasn't strictly a disease for sexually active gay men. Although it was still a concern of paramount importance to gay men, and that is where the film opens: with the first of many demonstrations seen over the course of its running time, in which Greenwich Village LGBT activists fight against the perception that a disease that only affects homosexuals isn't a big enough concern for the powers that be to seriously deal with fighting it. France captures this, and the rest of the movie, almost entirely through video shot at the time, edited with singular artfulness into a convincing narrative form. Talking heads crop up at limited intervals, to give some historical context or to draw lines between the events of 1987-1995 and later developments, but they make up an exceedingly small portion of the whole; the great bulk of the film comes in the form of crappy-looking VHS-originated home movies shot by the activists themselves, lending an extraordinarily intimate perspective to the whole affair.

The gripping rawness of its aesthetic is plainly one of the most important things about How to Survive a Plague, which isn't some nice, sober account of a terrible past. It's a bellowing scream from hell, whose title suggests a ravaged nightmare that the images more than provide: the low-resolution video adding a further layer of distortion to the wrecked bodies of the many AIDS victims who keep throwing themselves at the problem of making the government and pharmaceutical industries give enough of a damn to put real effort into fighting the further spread of the disease. It's shocking, disgusting, and emotionally devastating, a brutal reminder of how vicious and terrifying those days were, restoring some necessary immediacy to the subject matter in a world where AIDS is no longer a death sentence, or even a real barrier to living a normal, untroubled life (though the film does end with a title card in raging green informing us of the number of people who die every day of the disease even right now in 2012, after we've supposedly gotten a handle on it). And just so we never get comfortable, every time the film moves ahead a year, it's accompanied by a bland clock, tallying the total death tally in the world to that point, a number that starts out unbearably large and blows up as the film progresses.

Thus is the "plague" half of the title taken care of; of greater concern to France, and of course to the film's subjects, is the "survive" half. The film's narrative - and it is a singularly narrative film, for a historical retrospective documentary - is the life story of ACT UP, the activist group founded specifically to raise awareness of the fact that these AIDS victims dying on the streets were human beings who deserved respect and basic consideration by the people nominally in charge of their health and safety. As such, it is also the history of one of the most successful activist movements in contemporary history, recapping with a certain amount of puckish glee the sheer aggression with which ACT UP pursued its goals, a roaring rejoinder to the voices then and now who demand a more timid, diplomatic approach to activism; the response to moral obscenity is anger, argued the sick, their loved ones, and now this film celebrating them. That kind of flat-out endorsement of political extremism, coupled with nonstop proof of how it worked, smashingly well, is rather aggressive and brave of the movie itself - nowadays we tend to romanticise the peace-makers, not the shit-stirrers, even when the shit in question is in desperate need of it - and there's something awfully exciting in the movie's depiction of how it is genuinely possible for people to fight for a better life, or any life at all, and win it through sheer determination.

Even beyond that, the film works because it is so urgently human: it depicts all the suffering, outrage, and triumphs both great and small of a marginalised population finding its voice and requiring that they be given their due with extraordinary richness and power. The film is, ultimately, a history lesson, but history that is so immediate and alive that it's next to impossible not to be swept up in the intensity of it, and to feel all the heaving, dark emotions of those days; and to celebrate in those moments when celebration is due. The particular controversies the film depicts are largely dead and buried, but they continue to exist in different hidden forms, and How to Survive a Plague's brilliance lies in demonstrating exactly what made those days so important then, and continue to make their echoes important now.

Categories: documentaries, political movies