First world problems

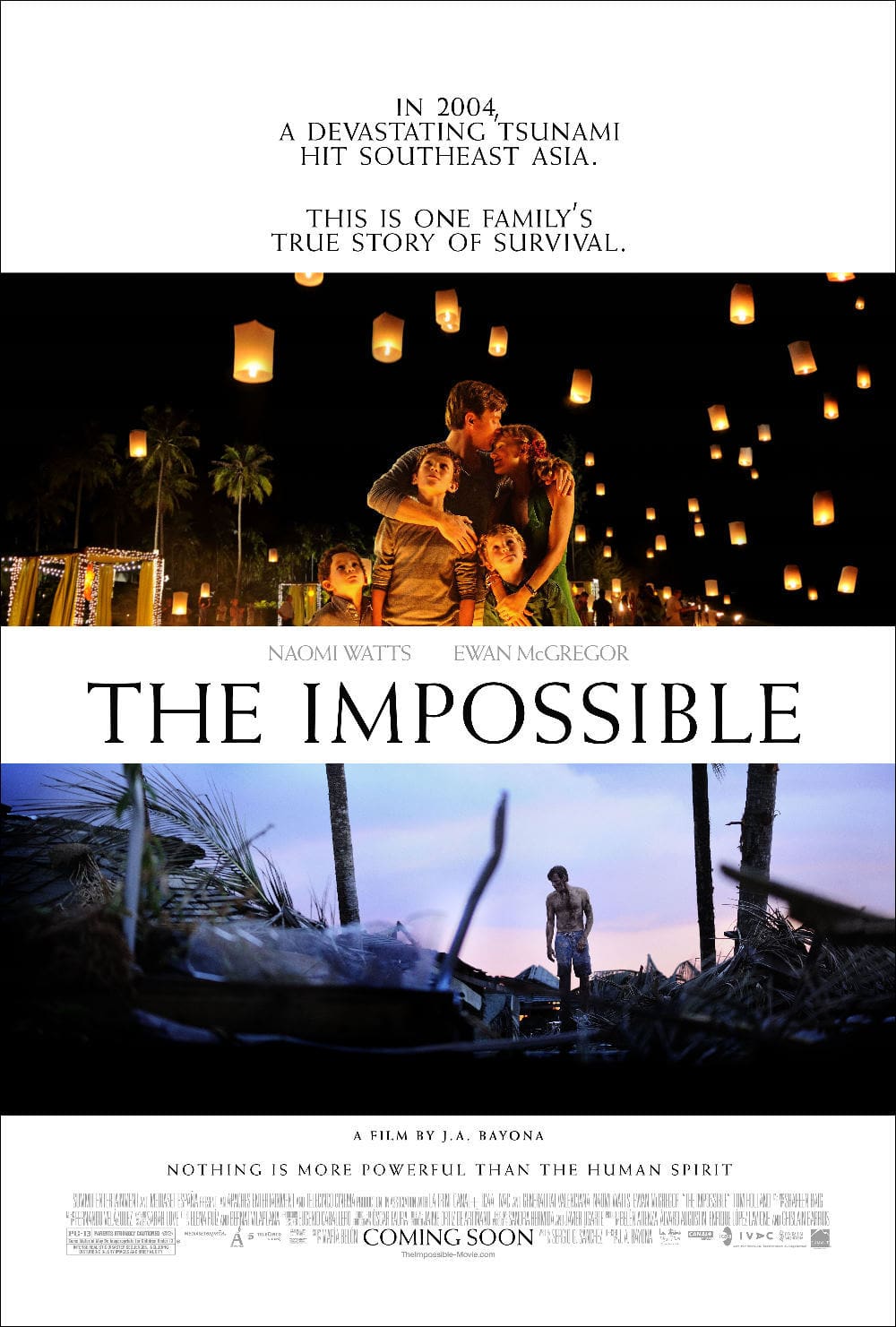

So as it turns out, the cultural hegemony angle on The Impossible is a bit of a non-starter. You know the one I'm talking about, if you've been paying much attention to the talk around the movie: the first major international film about the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami, which tells the story of how hundreds of thousands of impoverished Southeast Asian residents died in one of the worst natural disasters in history, through the lens of five white tourists who survived. "It's based on a true story!" declare the film's defenders, and the film itself, which stresses the words "true story" in an opening title card like only a movie that is uncomfortably aware that it has something to apologise for could do. Aye, and the true story happened to five Spanish citizens, not the Brits we see here, because even having made the jump from dead Thai people to living Europeans, the film - a Spanish production, mind you - still hadn't done it's work of middlebrowing everything up until it made sure the protagonists spoke English as well, and that, somehow, offends me even more than the initial decision to focus on Westerners.

That, as I was saying, is a non-starter. It is, undoubtedly, frustrating to explore a tragedy through such a mildewy lens of awards-baiting respectability; and if the movie were much better, that might actually be a real concern, as in e.g. Schindler's List, which is so famously about Jews not dying in the Holocaust. Sadly, The Impossible would have to do a great deal more just in order to get up to that level of exploitation: as it is, the movie we have is so limited in focus that the problem isn't that it discards the suffering of thousands of brown people, but that it doesn't care about anybody besides a single family that it does such a terribly poor job of presenting in an interesting way. The natives of Thailand serve as virtually nothing but set dressing, but even the other whites that the un-surnamed family encounters in their sojourn through a post-tsunami hellscape don't feel like living beings with their own stories, but mere props in the leads' adventure. This is never, ever more clear than in a pair of scenes where the dad, Henry (Ewan McGregor) is wandering through a refugee waystation, hoping to find those members of the family that he's been separated from, and asking a fellow survivor to borrow his phone. This gentleman replies that he is conserving battery in the expectation of the next emergency, which is, let's be honest, a sensible, reasonable thing to do, which is why we are encouraged to boo and hiss at him. A couple of scenes later, Henry is sitting in a circle of refugees, and one of the others lends his own phone, also noting that the battery is low, but in the spirit of camaraderie, he could not refuse; for his saintly act of charity, this man gets to watch - offscreen - as Henry bawls incomprehensibly in the middle of a conversation that really doesn't appear to have been all that immediately crucial even when he was forming real words.

Tunnel vision notwithstanding, I truly cannot see what about these people - Henry, his wife Maria (Naomi Watts), eldest son Lucas (Tom Holland) and interchangeable young sons Thomas (Samuel Joslin) and Simon (Oaklee Pendergast) - is supposed to be compelling, except in the most barbarically simple scheme of watching people suffer and then feeling good when they stop suffering. We hardly get to know anything about them before the tsunami hits 20 minutes in, and the rest of the two-part movie (part one: Maria and Lucas; part two: Henry, Thomas, and Simon) is so invested in basic survivalism that we never get a chance to afterwards, and while Watts, McGregor, and Holland all manage to find some way to demand our sympathy, their all fighting against a script by Sergio G. Sánchez that needlessly hamstrings them, particularly Watts, who is dumped into a near-coma at the halfway point and never has another thing to do besides look wan until the final scene; McGregor is stuck with a largely functional "where is my wife? have you seen my wife? where is my wife!?" part that unpleasantly recalls Harold Perrineau's two seasons of yelling "WAAALT!" all the time on Lost; Holland is actually the best of the three, keeping alive a sense of frenzied terror that should pervade the entire movie like toxic gas, but starts to leak out the instant that Watts finally gives in to her wounds around the 40-minute mark.

For this, you see, is the flipside: for all the tackiness of the last hour and change, as it descends into an undernourished character drama, the film opens terrifically well: the tsunami and the initial sense of dislocation that immediately follows are some of the best, most visceral action cinema of the year. Director Juan Antonio Bayona has directed only one previous feature, the 2007 horror picture The Orphanage (which, like this film, fumbled its character moments rather precariously), and on the evidence of both that and The Impossible, it seems like the right thing for him to do is stick with genre pictures; he's great at it. When The Impossible is focused solely on the chaos and intensity of being caught in a seemingly endless wall of crushing water, it is as gripping and effective as any movie has been all year; when it focuses with gruesome particularity for a PG-13 movie on the physical effects of that kind of violent trauma (Maria takes a gash in the leg early on, and from the first plumes of crimson spiking out into the water to the increasingly rancid appearance of her torn-up skin throughout her half of the movie, Bayona makes damn sure we feel everything about that kind of wound), it is as sickeningly you-are-there as the second half is detached.

The only thing more annoying than a movie that's slack and superficial throughout its running time is a movie with a profoundly great 25-minute chunk of top-shelf all-star filmmaking to really set off how measured and bland the rest of it is, and it's possible I like The Impossible less than it deserves simply because it's not all the tsunami sequence. Certainly, though, the movie has flaws, great ones: the weak characters, the episodic narrative development, the tedious reliance on farcically improbable close-calls between members of the broken family, the harsh and overly-polished cinematography that makes it all look something like Baz Luhrmann made a perfume ad for Oxfam. There are worse movies, and more cloyingly bourgeois Oscarbait, every single year, but something about how vigorously this one pursues its milquetoast second half is especially annoying.

That, as I was saying, is a non-starter. It is, undoubtedly, frustrating to explore a tragedy through such a mildewy lens of awards-baiting respectability; and if the movie were much better, that might actually be a real concern, as in e.g. Schindler's List, which is so famously about Jews not dying in the Holocaust. Sadly, The Impossible would have to do a great deal more just in order to get up to that level of exploitation: as it is, the movie we have is so limited in focus that the problem isn't that it discards the suffering of thousands of brown people, but that it doesn't care about anybody besides a single family that it does such a terribly poor job of presenting in an interesting way. The natives of Thailand serve as virtually nothing but set dressing, but even the other whites that the un-surnamed family encounters in their sojourn through a post-tsunami hellscape don't feel like living beings with their own stories, but mere props in the leads' adventure. This is never, ever more clear than in a pair of scenes where the dad, Henry (Ewan McGregor) is wandering through a refugee waystation, hoping to find those members of the family that he's been separated from, and asking a fellow survivor to borrow his phone. This gentleman replies that he is conserving battery in the expectation of the next emergency, which is, let's be honest, a sensible, reasonable thing to do, which is why we are encouraged to boo and hiss at him. A couple of scenes later, Henry is sitting in a circle of refugees, and one of the others lends his own phone, also noting that the battery is low, but in the spirit of camaraderie, he could not refuse; for his saintly act of charity, this man gets to watch - offscreen - as Henry bawls incomprehensibly in the middle of a conversation that really doesn't appear to have been all that immediately crucial even when he was forming real words.

Tunnel vision notwithstanding, I truly cannot see what about these people - Henry, his wife Maria (Naomi Watts), eldest son Lucas (Tom Holland) and interchangeable young sons Thomas (Samuel Joslin) and Simon (Oaklee Pendergast) - is supposed to be compelling, except in the most barbarically simple scheme of watching people suffer and then feeling good when they stop suffering. We hardly get to know anything about them before the tsunami hits 20 minutes in, and the rest of the two-part movie (part one: Maria and Lucas; part two: Henry, Thomas, and Simon) is so invested in basic survivalism that we never get a chance to afterwards, and while Watts, McGregor, and Holland all manage to find some way to demand our sympathy, their all fighting against a script by Sergio G. Sánchez that needlessly hamstrings them, particularly Watts, who is dumped into a near-coma at the halfway point and never has another thing to do besides look wan until the final scene; McGregor is stuck with a largely functional "where is my wife? have you seen my wife? where is my wife!?" part that unpleasantly recalls Harold Perrineau's two seasons of yelling "WAAALT!" all the time on Lost; Holland is actually the best of the three, keeping alive a sense of frenzied terror that should pervade the entire movie like toxic gas, but starts to leak out the instant that Watts finally gives in to her wounds around the 40-minute mark.

For this, you see, is the flipside: for all the tackiness of the last hour and change, as it descends into an undernourished character drama, the film opens terrifically well: the tsunami and the initial sense of dislocation that immediately follows are some of the best, most visceral action cinema of the year. Director Juan Antonio Bayona has directed only one previous feature, the 2007 horror picture The Orphanage (which, like this film, fumbled its character moments rather precariously), and on the evidence of both that and The Impossible, it seems like the right thing for him to do is stick with genre pictures; he's great at it. When The Impossible is focused solely on the chaos and intensity of being caught in a seemingly endless wall of crushing water, it is as gripping and effective as any movie has been all year; when it focuses with gruesome particularity for a PG-13 movie on the physical effects of that kind of violent trauma (Maria takes a gash in the leg early on, and from the first plumes of crimson spiking out into the water to the increasingly rancid appearance of her torn-up skin throughout her half of the movie, Bayona makes damn sure we feel everything about that kind of wound), it is as sickeningly you-are-there as the second half is detached.

The only thing more annoying than a movie that's slack and superficial throughout its running time is a movie with a profoundly great 25-minute chunk of top-shelf all-star filmmaking to really set off how measured and bland the rest of it is, and it's possible I like The Impossible less than it deserves simply because it's not all the tsunami sequence. Certainly, though, the movie has flaws, great ones: the weak characters, the episodic narrative development, the tedious reliance on farcically improbable close-calls between members of the broken family, the harsh and overly-polished cinematography that makes it all look something like Baz Luhrmann made a perfume ad for Oxfam. There are worse movies, and more cloyingly bourgeois Oscarbait, every single year, but something about how vigorously this one pursues its milquetoast second half is especially annoying.