Apocalypse Week: Death by the Bible

How right it is to celebrate Apocalypse Day, 21 December 2012, with a movie about the grandpappy of all apocalypses, the one that gave us the very word itself. For "apocalypse" does not come from any source referring to widespread destruction, be it in the form of meteors or tidal waves or carnivorous rabbits; it's derived from a Greek word variously translated, but close to "revelation of knowledge". As in the revelation. As in, "The Book of".

Yes, the apocalypse properly refers to only one thing: the end of times as described in the Revelation to St. John, the very last book of the Christian Bible, in which Christ returns to judge the living and the dead, the evil are cast for once and all into the fire, and the truly righteous will be seated next to God in Heaven for all eternity. Depending on your personal faith, it's either a complex metaphor for the political condition of 2nd Century Jerusalem; a literal, beat-by-beat depiction of exactly what is going to happen when God decides that enough is enough, and it's time to do something about this Satan character; or something that you don't care about, except to find it unbelievably terrifying when you know that it is literally believed by a man who can launch nuclear weapons.

Back in 1999, millennium fever was everywhere, and in certain fringy corners of evangelical Christianity, the expectation - and hope, let's be honest - was that the calendar ticking over from 1999 to 2000 was going to be the catalyst for the events of Revelation to finally start unfolding. We are all here; presumably then, this did not happen. Anyway, if I were a millenarian Christian, I'd have my sights set on 2033, the two-millennium anniversary of the Crucifixion, and not 1 January, 2000, the two-millennium anniversary of nothing at all (other than 1 January, 1 BCE, which nobody gives a shit about).

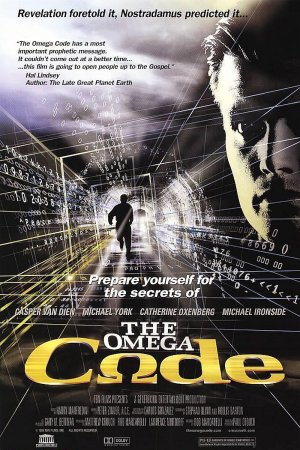

The point being, there was a whole mess of apocalyptic pop fiction getting cranked out in expectation of the Big Day, of which the biggest and most splashy was perhaps The Omega Code, released in October of 1999 and produced by Trinity Broadcasting Network, the kind of niche-market Christian message movie that gets produced with some frequency in places that mainstream filmgoers don't tend to pay attention to, and thus don't notice them; the difference is that The Omega Code, its producers savvily noting that millenarianism was big business all of a sudden, actually managed to populate it with a legit cast - or with Michael York and Michael Ironside, anyway, and Casper Van Dien, who was as legit in 1999 as he ever was before or since - and give it a for-real theatrical release. I cannot begin to imagine what their hopes or expectations were for this endeavor, but I am grateful to them anyway: for what they produced is no less than one of the best bad movies of the 1990s.

The plot is almost impossible to comfortably recount: as a "watch as the Apocalypse happens just like John said it would" movie made for people who have the Book of Revelation committed to memory, it feels at times like it's made up almost entirely of dog whistles and innuendo. But the short version is that motivational speaker and agnostic Gillen Lane (Van Dien) espouses the "Bible code", in which every letter of the Bible is part of an elaborate schema in which prophecies detailing everything that will happen for the rest of time - "how can you believe in the Bible code and not the content of the Bible?" sensibly asks chat show host Cassandra Barashe (Catherine Oxenberg), to which Gillen answers, essentially, "MY MOM DIED FUCK YOU", except he can't say "fuck" in a movie for fundamentalist Christians.

So anyway, he's an expert in the Bible code, which doesn't matter at all except that he's thus able to exposition it over to us, so that when we see it being used later on, we'll know what's happening. See, there's also this wealthy industrialist, Stone Alexander (York), trying to unlock the Bible code, so his lacky Dominic (Ironside) kills a rabbi to steal a key to doing just that - so he can use the Bible's prophecies to teach him how to take over the world. This involves things like ending world hunger and bringing peace to the Middle East, which is one of those dog whistles I was talking about - you and I might think that bringing peace to the Middle East would be a good thing, even the best thing ever, but to millenarians, that's merely a stepping stone in the Antichrist's plan to bring about the end times.

Gillen, who is a world-renowned motivational speaker when he's not talking about the Bible code, joins in with Alexander's team, seeing his works as a great boon to humanity, but the first-hand knowledge he thus gains of Alexander's evil motives - which quickly manifest themselves in things like getting elected President of the World - convinces him that something is a amiss. Thus it falls to him to fight Alexander's evil, though what, exactly, Gillen ever does over the course of the entire movie, other than fuck up his marriage, is never very clear: since the whole thing is wrapped up by a very literal deus ex machina, and Alexander is always several steps ahead of Gillen, our nominal protagonist really just spends the whole movie running around, looking scared.

Do please note, I have just shared with you the simple, dramatically unified version of the story, which is not at all how it's presented in the movie proper. The movie proper is a madcap collage of scenes that make a play for the target audience without providing much context at all, or explain how ideas and themes are stitched together: like the weaker Harry Potter adaptations, it's service for the fans who already know why a tossed-away line about rebuilding the Temple of Solomon is significant, for example, and thus don't need messy nonsense like "linearity" or "coherence to get in the way.

But the film is not merely, or even mostly, a failure of narrative - though certainly, it makes no sense on any level, dramatic or theological: e.g. the opening half of the movie makes it clear that Alexander is the Beast, and he even acts like he knows it; but then, midway through, he is actually possessed by the Beast - which is not, I think, how the Beast works - making it really unclear why he's been doing any of this. Also, the whole driving point of the story is that Alexander needs to unlock the Bible code, which involves the most nonsensical "we have heard about these 'computers' you speak of" technobabble that low-budget Christian television money could buy in 1999, so that he knows what to do next; but all the unlocked portions of the code are is even more cryptic descriptions of the events already in Revelation, or in the huge volume of commentary on Revelation. All that Alexander needed to make his evil plot come true was to follow Revelation itself, and not bother with this mysterious code, and then we could have cut Casper Van Dien out of the movie altogether.

As I was saying, the film's failures extend far beyond its writing, and Van Dien is as good a place as any to start: because he is fucking amazing in how vigorously out-of-control he is at every moment. His introduction involves jumping over the couch - twice! - at a daytime chat show, seven years before Tom Cruise made such behavior mainstream; every line he speaks sounds like it is the most important thing he's ever said, and he would be shouting if it didn't hurt so much to expel it from his body, so he can only use a clenched bark. Instead of facial expressions, he bares his teeth - his huge, huge teeth, which draw attention away from the rest of his face, and all the other actors onscreen as well.

Except for Michael York. He is glorious here: I have no idea if he chose to be part of the project because he truly believed in his message, or if it's merely because who wouldn't want to play Satan if they got the chance? I tend to assume the latter, or anyway, that is my hope: York is more purple than plums at the height of summer, more hammy than a Victorian Christmas dinner out of Dickens's most fantastic dreams, kitschier than the remainder bin at a Dollywood gift shop. He swans out in front of the camera and chomps on scenery with a connoisseur's refinement; he delivers opportunistic Shakespeare quotes with a rolling theatricality that crosses far beyond a simple parody of classical Shakespearean acting into something awe-inspiringly tacky.

York's performance alone would be worth checking out, but the film is a captivating miasma of ineptitude, all of it very earnest, all of it hilarious if you have even a small ability to enjoy bad filmmaking. Director Robert Marcarelli understands that he is making a thriller, but does not apparently understand what thrillers do, and so the film simply throughs portentous low angles at random places, while actors are encouraged to declaim rather than speak their lines. He misjudges tones completely - in a film where a large part of the character conflict lies in Gillen's attempts to fix his marriage, all the scenes between Gillen and Cassandra (whose name I gather exists solely so the screenwriters can demonstrate a reference pool larger than the books of Daniel and Revelation and a book of Shakespeare quotes) are all staged with the languidness of a cheap romantic thriller, while Gillen's poor wife (Devon Odessa) is presented as a fairly unambiguous nag - and fumbles the transition between places and timeframes badly. At one point, Gillen wakes up from a dream with a start, but it barely registers, since so many scenes seem to end in a similarly jagged way. The overall chintzy feeling to the production - never has a movie shot in the Holy Land felt so much like a cable movie made in Vancouver - is beyond the director's help, but he certainly could do less to accentuate it.

And no director, nor much better visual effects than the bargain basement CGI we get here, could have done anything with the last 20 minutes, in which Alexander fights a pair of taciturn angels and then God finally, irritated, does something about this whole mess (apparently, He was waiting for His chosen warrior Gillen to stop being such a dweeb), and ends the movie with one of the great "what? what just happened? wait, is that actually the end?" moments in modern filmmaking: as though, having killed off York, the filmmakers didn't care about any of the other plots or characters, and just had God through a giant god-nuke at the problem, wrapping the whole planet in the warm glow of a non-ending that is the perfect way to close off this deliriously ill-expressed slurry of melodramatic nonsense that has about as much to do with a serious consideration of theology as it does with a live-action Care Bears movie, and is very nearly as thrillingly daft. It would be almost impossible to imagine a more boldly terrible story of the Christian apocalypse - almost impossible, I say...

Yes, the apocalypse properly refers to only one thing: the end of times as described in the Revelation to St. John, the very last book of the Christian Bible, in which Christ returns to judge the living and the dead, the evil are cast for once and all into the fire, and the truly righteous will be seated next to God in Heaven for all eternity. Depending on your personal faith, it's either a complex metaphor for the political condition of 2nd Century Jerusalem; a literal, beat-by-beat depiction of exactly what is going to happen when God decides that enough is enough, and it's time to do something about this Satan character; or something that you don't care about, except to find it unbelievably terrifying when you know that it is literally believed by a man who can launch nuclear weapons.

Back in 1999, millennium fever was everywhere, and in certain fringy corners of evangelical Christianity, the expectation - and hope, let's be honest - was that the calendar ticking over from 1999 to 2000 was going to be the catalyst for the events of Revelation to finally start unfolding. We are all here; presumably then, this did not happen. Anyway, if I were a millenarian Christian, I'd have my sights set on 2033, the two-millennium anniversary of the Crucifixion, and not 1 January, 2000, the two-millennium anniversary of nothing at all (other than 1 January, 1 BCE, which nobody gives a shit about).

The point being, there was a whole mess of apocalyptic pop fiction getting cranked out in expectation of the Big Day, of which the biggest and most splashy was perhaps The Omega Code, released in October of 1999 and produced by Trinity Broadcasting Network, the kind of niche-market Christian message movie that gets produced with some frequency in places that mainstream filmgoers don't tend to pay attention to, and thus don't notice them; the difference is that The Omega Code, its producers savvily noting that millenarianism was big business all of a sudden, actually managed to populate it with a legit cast - or with Michael York and Michael Ironside, anyway, and Casper Van Dien, who was as legit in 1999 as he ever was before or since - and give it a for-real theatrical release. I cannot begin to imagine what their hopes or expectations were for this endeavor, but I am grateful to them anyway: for what they produced is no less than one of the best bad movies of the 1990s.

The plot is almost impossible to comfortably recount: as a "watch as the Apocalypse happens just like John said it would" movie made for people who have the Book of Revelation committed to memory, it feels at times like it's made up almost entirely of dog whistles and innuendo. But the short version is that motivational speaker and agnostic Gillen Lane (Van Dien) espouses the "Bible code", in which every letter of the Bible is part of an elaborate schema in which prophecies detailing everything that will happen for the rest of time - "how can you believe in the Bible code and not the content of the Bible?" sensibly asks chat show host Cassandra Barashe (Catherine Oxenberg), to which Gillen answers, essentially, "MY MOM DIED FUCK YOU", except he can't say "fuck" in a movie for fundamentalist Christians.

So anyway, he's an expert in the Bible code, which doesn't matter at all except that he's thus able to exposition it over to us, so that when we see it being used later on, we'll know what's happening. See, there's also this wealthy industrialist, Stone Alexander (York), trying to unlock the Bible code, so his lacky Dominic (Ironside) kills a rabbi to steal a key to doing just that - so he can use the Bible's prophecies to teach him how to take over the world. This involves things like ending world hunger and bringing peace to the Middle East, which is one of those dog whistles I was talking about - you and I might think that bringing peace to the Middle East would be a good thing, even the best thing ever, but to millenarians, that's merely a stepping stone in the Antichrist's plan to bring about the end times.

Gillen, who is a world-renowned motivational speaker when he's not talking about the Bible code, joins in with Alexander's team, seeing his works as a great boon to humanity, but the first-hand knowledge he thus gains of Alexander's evil motives - which quickly manifest themselves in things like getting elected President of the World - convinces him that something is a amiss. Thus it falls to him to fight Alexander's evil, though what, exactly, Gillen ever does over the course of the entire movie, other than fuck up his marriage, is never very clear: since the whole thing is wrapped up by a very literal deus ex machina, and Alexander is always several steps ahead of Gillen, our nominal protagonist really just spends the whole movie running around, looking scared.

Do please note, I have just shared with you the simple, dramatically unified version of the story, which is not at all how it's presented in the movie proper. The movie proper is a madcap collage of scenes that make a play for the target audience without providing much context at all, or explain how ideas and themes are stitched together: like the weaker Harry Potter adaptations, it's service for the fans who already know why a tossed-away line about rebuilding the Temple of Solomon is significant, for example, and thus don't need messy nonsense like "linearity" or "coherence to get in the way.

But the film is not merely, or even mostly, a failure of narrative - though certainly, it makes no sense on any level, dramatic or theological: e.g. the opening half of the movie makes it clear that Alexander is the Beast, and he even acts like he knows it; but then, midway through, he is actually possessed by the Beast - which is not, I think, how the Beast works - making it really unclear why he's been doing any of this. Also, the whole driving point of the story is that Alexander needs to unlock the Bible code, which involves the most nonsensical "we have heard about these 'computers' you speak of" technobabble that low-budget Christian television money could buy in 1999, so that he knows what to do next; but all the unlocked portions of the code are is even more cryptic descriptions of the events already in Revelation, or in the huge volume of commentary on Revelation. All that Alexander needed to make his evil plot come true was to follow Revelation itself, and not bother with this mysterious code, and then we could have cut Casper Van Dien out of the movie altogether.

As I was saying, the film's failures extend far beyond its writing, and Van Dien is as good a place as any to start: because he is fucking amazing in how vigorously out-of-control he is at every moment. His introduction involves jumping over the couch - twice! - at a daytime chat show, seven years before Tom Cruise made such behavior mainstream; every line he speaks sounds like it is the most important thing he's ever said, and he would be shouting if it didn't hurt so much to expel it from his body, so he can only use a clenched bark. Instead of facial expressions, he bares his teeth - his huge, huge teeth, which draw attention away from the rest of his face, and all the other actors onscreen as well.

Except for Michael York. He is glorious here: I have no idea if he chose to be part of the project because he truly believed in his message, or if it's merely because who wouldn't want to play Satan if they got the chance? I tend to assume the latter, or anyway, that is my hope: York is more purple than plums at the height of summer, more hammy than a Victorian Christmas dinner out of Dickens's most fantastic dreams, kitschier than the remainder bin at a Dollywood gift shop. He swans out in front of the camera and chomps on scenery with a connoisseur's refinement; he delivers opportunistic Shakespeare quotes with a rolling theatricality that crosses far beyond a simple parody of classical Shakespearean acting into something awe-inspiringly tacky.

York's performance alone would be worth checking out, but the film is a captivating miasma of ineptitude, all of it very earnest, all of it hilarious if you have even a small ability to enjoy bad filmmaking. Director Robert Marcarelli understands that he is making a thriller, but does not apparently understand what thrillers do, and so the film simply throughs portentous low angles at random places, while actors are encouraged to declaim rather than speak their lines. He misjudges tones completely - in a film where a large part of the character conflict lies in Gillen's attempts to fix his marriage, all the scenes between Gillen and Cassandra (whose name I gather exists solely so the screenwriters can demonstrate a reference pool larger than the books of Daniel and Revelation and a book of Shakespeare quotes) are all staged with the languidness of a cheap romantic thriller, while Gillen's poor wife (Devon Odessa) is presented as a fairly unambiguous nag - and fumbles the transition between places and timeframes badly. At one point, Gillen wakes up from a dream with a start, but it barely registers, since so many scenes seem to end in a similarly jagged way. The overall chintzy feeling to the production - never has a movie shot in the Holy Land felt so much like a cable movie made in Vancouver - is beyond the director's help, but he certainly could do less to accentuate it.

And no director, nor much better visual effects than the bargain basement CGI we get here, could have done anything with the last 20 minutes, in which Alexander fights a pair of taciturn angels and then God finally, irritated, does something about this whole mess (apparently, He was waiting for His chosen warrior Gillen to stop being such a dweeb), and ends the movie with one of the great "what? what just happened? wait, is that actually the end?" moments in modern filmmaking: as though, having killed off York, the filmmakers didn't care about any of the other plots or characters, and just had God through a giant god-nuke at the problem, wrapping the whole planet in the warm glow of a non-ending that is the perfect way to close off this deliriously ill-expressed slurry of melodramatic nonsense that has about as much to do with a serious consideration of theology as it does with a live-action Care Bears movie, and is very nearly as thrillingly daft. It would be almost impossible to imagine a more boldly terrible story of the Christian apocalypse - almost impossible, I say...