The 48th Chicago International Film Festival

Screens at CIFF: 10/13 & 10/14 & 10/21

World premiere: 7 September, 2012, Toronto International Film Festival

2011's Weekend is a great film. A bracing film. A film that I'd recommend to everybody, gay or straight, interested in seeing two men navigate a single difficult romantic entanglement that arises in part from the assumptions they make about social identity. More importantly, Weekend is not a movie that wants badly to be made over again, because there's no way to capture that kind of singularity a second time; the film's impact, in part, comes about because it is so adamantly about gay men without agitating on behalf of gay men, and that trick can't be played a second time. Not so soon. And that is why the opening of Out in the Dark made me profoundly irritated: presumably without being a deliberate copy of Weekend (it was surely in production long before the earlier film was widely-seen), it managed to hit almost all of the same notes to considerably lesser effect, and the promise of being "just like that really good movie from last year, only it's a Romeo and Juliet scenario involving the Israel/Palestine conflict" was somehow even worse.

So the good news, then, is that Out in the Dark is mostly not at all like Weekend; in part because it is much more interested in being one in a long tradition of Israeli-produced movies about how Israel needs to back the fuck off of the way it treats Palestinian Arabs, than in being a movie about lovers, gay or otherwise; I think it's largely fair to say that co-writers Michael Mayer & Yael Shafrir are more interested in using homosexuality as a tool to explore Palestinian political issues than the other way around. And perhaps this impression is strengthened because the Israeli half of this politically-torn love story is such a bland cipher, given only the exact amount of personalty he needs in order to serve the needs of the greater plot, and not nearly enough to come across as a romantic co-lead, and thus does the love story shrink and wither for want of emotional nourishment.

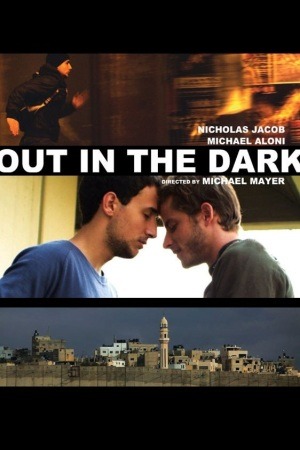

The lovers, who meet at a Tel Aviv gay club in the opening scene, are Palestinian Nimr Mashrawi (Nicholas Jacob), a psychology graduate student at an Israeli school with an extraordinarily precious pass that gives him a rare freedom to wander unmolested in the greater, unoccupied part of Israel, whose brother Nabil (Jamil Khoury) is hoarding guns for acts of terrorism; and Roy Schaefer (Michael Aloni), a lawyer. The plot in which they find themselves is reasonably straightforward: a little while after they meet, they start to hook up, and after a while of hooking up, they're pretty comfortable with living and acting like a couple, though there's only so far this can go with Nimr being forced to live as though absolutely nothing is happening, lest he incur the wrath of his unhinged brother for being too chummy with an Israeli, or the wrath of his entire community for being homosexual. And because the lovers aren't concerned about discretion in the relative safety of Tel Aviv, Nimr ends up being hauled in by intelligence officers who hold both his pass and his identity in ransom: spill the beans on his brother's activity, or things will get very bad, very quickly.

And it's this second narrative thread, in which Nimr is thrust into the position of pawn, caught between his love for Roy, his desire to remain true to his race, his dislike of Nabil's methods, and his affection for his family, that makes Out in the Dark work; the point at which it becomes an actively political movie, throwing this simple, uncomplicated man into a bureaucratic mire and watching him suffer the loss of love and family and security, all because the world he lives in is unconcerned with the human cost of the political conflict that's a part of everyday existence, that is the point at which Out in the Dark picks up real momentum and high stakes, at which Jacob's performance really starts to gel and Nimr becomes a tragic figure rather than just a vessel for a love story.

The wrinkle of addressing Palestinian cultural norms as they apply to sexuality gives the film some novel impact, as does its depiction of modern life in a society so pridefully reliant on tradition (on two separate occasions, Nimr is caught because he doesn't stop to think about what happens in a world where phones - phones with cameras - are ubiquitous); and though Mayer's direction is functional more than it is exciting, he captures something about the feeling of Tel Aviv life that feels real and visceral, unlike the tendency of some Israeli films to be so much about their broader social message that any actual observation about the people they're depiction gets lost.

And then, it always comes back to the fact that the drama hinges, consistently, on the deep and abiding love between Nimr and Roy; this love creates the greater conflict and is also the way that the protagonist fights back in that conflict; it is the reason most of the plot happens. And, from where I'm sitting, it doesn't work. The couple progresses from "slightly awkward hook-up" to "inseparable soul mates" in such a short span of onscreen time that it hardly seems credible that either of them could be nearly invested enough for the subsequent events to make sense; and even without that objection (after all, this is a movie; people fall in love quick in movies), there's still Roy, who's a complete blank of a character, performed by Aloni in such a way to exaggerate, rather than mitigate, how little defined personality he's given. He exists, seemingly, just to be in love with Nimr, not to have any inner life of his own, and that is a tremendous lapse for a movie in which so much rests on a passionate love affair. Sociologically, the film is fascinating; dramatically, it is a borderline disaster.

7/10

World premiere: 7 September, 2012, Toronto International Film Festival

2011's Weekend is a great film. A bracing film. A film that I'd recommend to everybody, gay or straight, interested in seeing two men navigate a single difficult romantic entanglement that arises in part from the assumptions they make about social identity. More importantly, Weekend is not a movie that wants badly to be made over again, because there's no way to capture that kind of singularity a second time; the film's impact, in part, comes about because it is so adamantly about gay men without agitating on behalf of gay men, and that trick can't be played a second time. Not so soon. And that is why the opening of Out in the Dark made me profoundly irritated: presumably without being a deliberate copy of Weekend (it was surely in production long before the earlier film was widely-seen), it managed to hit almost all of the same notes to considerably lesser effect, and the promise of being "just like that really good movie from last year, only it's a Romeo and Juliet scenario involving the Israel/Palestine conflict" was somehow even worse.

So the good news, then, is that Out in the Dark is mostly not at all like Weekend; in part because it is much more interested in being one in a long tradition of Israeli-produced movies about how Israel needs to back the fuck off of the way it treats Palestinian Arabs, than in being a movie about lovers, gay or otherwise; I think it's largely fair to say that co-writers Michael Mayer & Yael Shafrir are more interested in using homosexuality as a tool to explore Palestinian political issues than the other way around. And perhaps this impression is strengthened because the Israeli half of this politically-torn love story is such a bland cipher, given only the exact amount of personalty he needs in order to serve the needs of the greater plot, and not nearly enough to come across as a romantic co-lead, and thus does the love story shrink and wither for want of emotional nourishment.

The lovers, who meet at a Tel Aviv gay club in the opening scene, are Palestinian Nimr Mashrawi (Nicholas Jacob), a psychology graduate student at an Israeli school with an extraordinarily precious pass that gives him a rare freedom to wander unmolested in the greater, unoccupied part of Israel, whose brother Nabil (Jamil Khoury) is hoarding guns for acts of terrorism; and Roy Schaefer (Michael Aloni), a lawyer. The plot in which they find themselves is reasonably straightforward: a little while after they meet, they start to hook up, and after a while of hooking up, they're pretty comfortable with living and acting like a couple, though there's only so far this can go with Nimr being forced to live as though absolutely nothing is happening, lest he incur the wrath of his unhinged brother for being too chummy with an Israeli, or the wrath of his entire community for being homosexual. And because the lovers aren't concerned about discretion in the relative safety of Tel Aviv, Nimr ends up being hauled in by intelligence officers who hold both his pass and his identity in ransom: spill the beans on his brother's activity, or things will get very bad, very quickly.

And it's this second narrative thread, in which Nimr is thrust into the position of pawn, caught between his love for Roy, his desire to remain true to his race, his dislike of Nabil's methods, and his affection for his family, that makes Out in the Dark work; the point at which it becomes an actively political movie, throwing this simple, uncomplicated man into a bureaucratic mire and watching him suffer the loss of love and family and security, all because the world he lives in is unconcerned with the human cost of the political conflict that's a part of everyday existence, that is the point at which Out in the Dark picks up real momentum and high stakes, at which Jacob's performance really starts to gel and Nimr becomes a tragic figure rather than just a vessel for a love story.

The wrinkle of addressing Palestinian cultural norms as they apply to sexuality gives the film some novel impact, as does its depiction of modern life in a society so pridefully reliant on tradition (on two separate occasions, Nimr is caught because he doesn't stop to think about what happens in a world where phones - phones with cameras - are ubiquitous); and though Mayer's direction is functional more than it is exciting, he captures something about the feeling of Tel Aviv life that feels real and visceral, unlike the tendency of some Israeli films to be so much about their broader social message that any actual observation about the people they're depiction gets lost.

And then, it always comes back to the fact that the drama hinges, consistently, on the deep and abiding love between Nimr and Roy; this love creates the greater conflict and is also the way that the protagonist fights back in that conflict; it is the reason most of the plot happens. And, from where I'm sitting, it doesn't work. The couple progresses from "slightly awkward hook-up" to "inseparable soul mates" in such a short span of onscreen time that it hardly seems credible that either of them could be nearly invested enough for the subsequent events to make sense; and even without that objection (after all, this is a movie; people fall in love quick in movies), there's still Roy, who's a complete blank of a character, performed by Aloni in such a way to exaggerate, rather than mitigate, how little defined personality he's given. He exists, seemingly, just to be in love with Nimr, not to have any inner life of his own, and that is a tremendous lapse for a movie in which so much rests on a passionate love affair. Sociologically, the film is fascinating; dramatically, it is a borderline disaster.

7/10