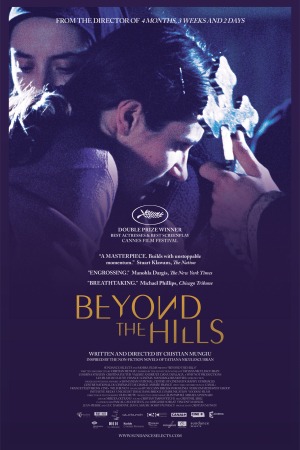

The 48th Chicago International Film Festival

Screens at CIFF: 10/12 & 10/15

World premiere: 19 May, 2012, Cannes Film Festival

We do not dislike Beyond the Hills - this is as much an affirmation as a preemptive clarification. It would be quite impossible to dislike in which so much, for such a large part of the running time, is amazing. Nor do we hold it against Cristian Mungiu's first feature after 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days that it feels a bit of a letdown. After all, if we felt that way about all movies not as good as 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days, there'd be no reason to keep going to movies, and if Mungiu never matches that film's level of accomplishment again, he's still got plenty of room in which to make plenty of truly outstanding motion pictures. But this isn't one of them, I don't think, and coming to that decision has been among the absolute hardest things I've had to do as a cinephile all year - after all, this is the freaking follow-up to 4 Months, which makes it for pretentious film buffs as The Avengers 2 is for normal people.

Viewed in the abstract, this is almost like a subdued, savagely Eastern European version of nunsploitation: now in their mid-20s, Voichiţa (Cosmina Stratan) and Alina (Cristina Flutur) used to be best friends together at the orphanage where they grew up; since being obliged to leave, Alina has gone on to unspecified work in Germany that has failed her, while Voichiţa has taken up the life of a sister in a remote monastery ruled with unyielding orthodoxy by its priest (Valeriu Andriuţă). The two girls are united, as the film opens, in a steaming trainyard so noisy that they have to shriek to communicate, and we can still barely hear them - the first of a long series of moments that are brilliantly conceived in their own right and don't necessarily build on one another - and Voichiţa excitedly takes Alina back to the monastery where she is convinced that her beloved friend will find the peace that has clearly been evading her ever since their orphanage days, ideally by giving herself over to the love of God. Alina, for her part, has seen too many things to confidently assert that God is all that loving to begin with, and she views the confines of the monastery less as a place of sanctity and spirituality than as a petty dictatorship that has turned her best and only friend into a drone; she makes it her immediate goal to bring Voichiţa with her when she leaves.

Eventually, this ends with the well-meaning sisters and priest, so unaccustomed to any other opinions than the one that fill their tiny, hyper-religious, insistently anti-modern world (they don't even have electricity), convinced that Alina is possessed by Satan, and they stage a rather amateurish but intensely sincere exorcism that takes up a sizable chunk of the end of the movie. I will not spoil how this turns out, but Beyond the Hills was inspired by an event that happened in Romania in 2005, and it's hard to imagine any happy version of this story being newsworthy enough to inspire a movie.

So it's nunsploitation-ey, because it ultimately turns into a singularly anti-exploitative exorcism movie; also because it is implied in ways so bold that I honestly didn't even think it still counted as exploitation that Voichiţa and Alina were, in addition to best friends, lovers - Alina inviting Voichiţa to massage her breasts with rubbing alcohol, and complaining that they're sleeping in separate beds being two of the bigger tells. Which is more nunsploitation-ey still. Indeed, it is the quintessence of nunsploitation.

It's also one of a great many threads that Beyond the Hills just doesn't seem very interested in pursuing. I might even go so far as to say that every thread is one Beyond the Hills doesn't seem very interested in pursuing; there's not a single theme, or character arc, or even narrative throughline that isn't completely absent for at last a fifth of the movie's two-and-a-half hours - and if ever I saw a movie that would have improved, maybe even become a straight-up masterpiece, for being shorter, it's this one: that's a lot of space Mungiu has given himself to work in, and there's a lot of looseness that results. Slice a half-hour off the film, and suddenly there's not so much wiggle room, and maybe we can get something that's tight and controlled.

Certainly, it's easy to admire Mungiu's desire to push in such a vastly different direction than 4 Months, and not just in terms of the new film's sprawling narrative: every major Romanian film of the last several years, from The Death of Mr. Lăzărescu to Tuesday, After Christmas, has subscribed to basically the same aesthetic style: infinitely long takes that move a little or not at all. Beyond the Hills pushes against that, using considerably more cutting and hectic camerawork - the scene of Alina being captured by the sisters, to begin their exorcism, is a legitimately terrifying moment, almost entirely because of how deranged and wild the camera is at that time - and while it's still an awfully still and slow movie, in the context of the Romanian New Wave, it's the next thing to Baz Luhrmann.

And if the aesthetic shift pays off, giving the film more energy and turning into an unexpected thriller in which the collision of Alina and the rest of the monastery becomes more and more inevitable, the narrative shift doesn't, necessarily. Beyond the Hills is a deeply unfocused movie; just how unfocused can be indicated by the fact that everything I've said sets up an Alina vs. everyone else conflict, and yet if the film has a sole protagonist, it's certainly Voichiţa. For all that it matters, though; the film lacks the clear story development that makes a quantification like "protagonist" meaningful. There are great character moments for both girls, and there are long passages where the script and director let the actresses (both making their film debuts) down completely. Just like, depending on where you are in the film, and which shot you end on, changes the theme between one of a half-dozen distinct possibilities; if "the separation between traditional and modern values" seems to be the winner, it's only because it's the one implied by a slow track forward past the sisters during the final shot.

Perhaps this is ugly ol' auteurism speaking, and perhaps just a latent desire for every Romanian film to actually be a life-changing masterpiece: I want all this apparent messiness to be so cunning that I'm too stupid to understand the film, not that the film is too diffuse to work properly. Let us say that I'm not hugely eager for a re-watch in the near future, either way.

7/10

World premiere: 19 May, 2012, Cannes Film Festival

We do not dislike Beyond the Hills - this is as much an affirmation as a preemptive clarification. It would be quite impossible to dislike in which so much, for such a large part of the running time, is amazing. Nor do we hold it against Cristian Mungiu's first feature after 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days that it feels a bit of a letdown. After all, if we felt that way about all movies not as good as 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days, there'd be no reason to keep going to movies, and if Mungiu never matches that film's level of accomplishment again, he's still got plenty of room in which to make plenty of truly outstanding motion pictures. But this isn't one of them, I don't think, and coming to that decision has been among the absolute hardest things I've had to do as a cinephile all year - after all, this is the freaking follow-up to 4 Months, which makes it for pretentious film buffs as The Avengers 2 is for normal people.

Viewed in the abstract, this is almost like a subdued, savagely Eastern European version of nunsploitation: now in their mid-20s, Voichiţa (Cosmina Stratan) and Alina (Cristina Flutur) used to be best friends together at the orphanage where they grew up; since being obliged to leave, Alina has gone on to unspecified work in Germany that has failed her, while Voichiţa has taken up the life of a sister in a remote monastery ruled with unyielding orthodoxy by its priest (Valeriu Andriuţă). The two girls are united, as the film opens, in a steaming trainyard so noisy that they have to shriek to communicate, and we can still barely hear them - the first of a long series of moments that are brilliantly conceived in their own right and don't necessarily build on one another - and Voichiţa excitedly takes Alina back to the monastery where she is convinced that her beloved friend will find the peace that has clearly been evading her ever since their orphanage days, ideally by giving herself over to the love of God. Alina, for her part, has seen too many things to confidently assert that God is all that loving to begin with, and she views the confines of the monastery less as a place of sanctity and spirituality than as a petty dictatorship that has turned her best and only friend into a drone; she makes it her immediate goal to bring Voichiţa with her when she leaves.

Eventually, this ends with the well-meaning sisters and priest, so unaccustomed to any other opinions than the one that fill their tiny, hyper-religious, insistently anti-modern world (they don't even have electricity), convinced that Alina is possessed by Satan, and they stage a rather amateurish but intensely sincere exorcism that takes up a sizable chunk of the end of the movie. I will not spoil how this turns out, but Beyond the Hills was inspired by an event that happened in Romania in 2005, and it's hard to imagine any happy version of this story being newsworthy enough to inspire a movie.

So it's nunsploitation-ey, because it ultimately turns into a singularly anti-exploitative exorcism movie; also because it is implied in ways so bold that I honestly didn't even think it still counted as exploitation that Voichiţa and Alina were, in addition to best friends, lovers - Alina inviting Voichiţa to massage her breasts with rubbing alcohol, and complaining that they're sleeping in separate beds being two of the bigger tells. Which is more nunsploitation-ey still. Indeed, it is the quintessence of nunsploitation.

It's also one of a great many threads that Beyond the Hills just doesn't seem very interested in pursuing. I might even go so far as to say that every thread is one Beyond the Hills doesn't seem very interested in pursuing; there's not a single theme, or character arc, or even narrative throughline that isn't completely absent for at last a fifth of the movie's two-and-a-half hours - and if ever I saw a movie that would have improved, maybe even become a straight-up masterpiece, for being shorter, it's this one: that's a lot of space Mungiu has given himself to work in, and there's a lot of looseness that results. Slice a half-hour off the film, and suddenly there's not so much wiggle room, and maybe we can get something that's tight and controlled.

Certainly, it's easy to admire Mungiu's desire to push in such a vastly different direction than 4 Months, and not just in terms of the new film's sprawling narrative: every major Romanian film of the last several years, from The Death of Mr. Lăzărescu to Tuesday, After Christmas, has subscribed to basically the same aesthetic style: infinitely long takes that move a little or not at all. Beyond the Hills pushes against that, using considerably more cutting and hectic camerawork - the scene of Alina being captured by the sisters, to begin their exorcism, is a legitimately terrifying moment, almost entirely because of how deranged and wild the camera is at that time - and while it's still an awfully still and slow movie, in the context of the Romanian New Wave, it's the next thing to Baz Luhrmann.

And if the aesthetic shift pays off, giving the film more energy and turning into an unexpected thriller in which the collision of Alina and the rest of the monastery becomes more and more inevitable, the narrative shift doesn't, necessarily. Beyond the Hills is a deeply unfocused movie; just how unfocused can be indicated by the fact that everything I've said sets up an Alina vs. everyone else conflict, and yet if the film has a sole protagonist, it's certainly Voichiţa. For all that it matters, though; the film lacks the clear story development that makes a quantification like "protagonist" meaningful. There are great character moments for both girls, and there are long passages where the script and director let the actresses (both making their film debuts) down completely. Just like, depending on where you are in the film, and which shot you end on, changes the theme between one of a half-dozen distinct possibilities; if "the separation between traditional and modern values" seems to be the winner, it's only because it's the one implied by a slow track forward past the sisters during the final shot.

Perhaps this is ugly ol' auteurism speaking, and perhaps just a latent desire for every Romanian film to actually be a life-changing masterpiece: I want all this apparent messiness to be so cunning that I'm too stupid to understand the film, not that the film is too diffuse to work properly. Let us say that I'm not hugely eager for a re-watch in the near future, either way.

7/10

Categories: balkan cinema, exorcising, movies for pretentious people, romanian cinema, thrillers