Blockbuster History: Men with bikes

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: at the time of this writing, Premium Rush has already spectacularly failed to be a blockbuster or even a film likely to break even on its production budget. But I will still use it to dip into the long and storied history of films documenting our culture's deep and abiding love of that noblest of all vehicles, the bicycle.

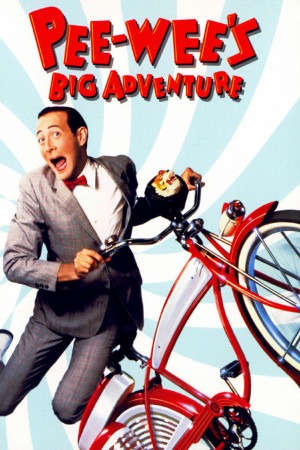

The chief attraction of the 1985 film Pee-wee's Big Adventure since sometime early in the 1990s has been that it was the first feature directed by Tim Burton. But this was not always the case: in 1985 itself, for example, Tim Burton was known, if at all, by a small and self-selective audience of animation fans who would know him only for the stop-motion short Vincent that he was allowed to direct during his unhappy stay at Walt Disney Animation. At that time, of course, the more obvious point of appeal would have been...

Well, that's the hell of it. Look at it from any angle you want, but Pee-wee's Big Adventure is a stupefyingly weird idea for a movie: the character of Pee-wee Herman, created by stand-up comic and Groundlings member Paul Reubens in the late '70s, had been the centerpiece of a midnight stage show in Los Angeles that was hugely successful as midnight stage shows go, getting the actor some nationwide prominence on TV chat shows, but that's a limited sort of fame at best. And yet, Pee-wee's Big Adventure was greenlit by Warner Bros. on the strength of literally no script at all, just the studio's faith that Reubens would be able to deliver something of merit. Even weirder: it worked. The film made back its $6 million budget more than six times over, inspiring the creation of a TV show based around Reubens' character, Pee-wee's Playhouse, which was enough to make the nasal man-child one of the biggest pop culture figures in America in the back half of the 1980s (we had some really fucking weird pop culture back in the 1980s - a bull terrier hawking beer was almost as big in those days as Pee-wee was). It also set Burton on the very fast, very short track that ended with the huge-budget blockbuster Batman four years and two movies later. Happy endings for everybody, then!

Looking back with years of Burton steadily making himself a household name and then a brand, there's not all that much of the "Burtonesque" to Pee-wee's Big Adventure outside of a few scenes, chief among them a nightmare involving abnormally freakish clowns performing surgery on a bicycle in an environment made up of neon tubes and canted surfaces covered in a black-and-white checkerboard pattern, and a strange hitchhiker lady whose face explodes in some kind of family-friendly, PG-rated body horror that was the main reason I did not watch this film even a single time between the time it scared the ever-loving shit out of me when I was 7 and sometime in my early 20s. Outside of this, there is nothing of the way that his earlier shorts, Vincent and Frankenweenie, speak to the aesthetic he'd so assiduously cultivate, or that even his sophomore feature, Beetlejuice, looks for all the world like the movies he'd still be making 15 and 20 years down the road. And yet, Burton was an inspired choice to direct, maybe the best choice in the mid-'80s, because Pee-wee Herman as a concept is basically a cartoon character - Reubens's flexible, rubbery voice alone would drive us to that conclusion - and the wall-to-wall wackiness that makes up Pee-wee's Big Adventure is cartoon logic through and through. And the thing about Tim Burton that is easy to forget, is that he was by training, at the beginning of his career, an animator, something that's obvious from the first moments of the film and never lets up. It's not quite as formally bracing as when Looney Tunes director Frank Tashlin started applying the visual storytelling of the animated comic short to live-action features in the '40s and '50s, but Pee-wee's Big Adventure is chiefly successful because of its commitment to an artistic ideal: make something that looks, talks, feels, and moves like a cartoon.

A lot of that has to do with Reubens himself, of course, whose physical immersion into the Pee-wee Herman role is almost terrifying in its enthusiasm. And a lot, as well, owes to composer Danny Elfman, writing only his second film score, the first for a movie not written and directed by his brother: the Oingo Boingo singer, hired by Burton on a profoundly lucky whim, is the film's rather obvious secret weapon, laying a musical foundation for all the warped activities that bounces and sidles around crazily, owing a clear debt to Nino Rota's music for 8½, but bent around and jazzed up like a meth binge. Burton himself supplies a searingly bright color palette and a perfectly-aimed visual sense of humor.

Above and beyond all this, though, the film's screenplay is just right for the movie it wants to be: concocted by Reubens with fellow Groundling Phil Hartman, and Michael Varhol, it starts off by posting an impossible character - a grown man with the emotional maturity of an 8-year-old who nevertheless functions as an entirely self-sufficient, well-liked member of his community - and a ridiculous scenario, in which Pee-wee's beloved bike (the kind with pedals, not the kind with a motor in it) is stolen by fellow man-child and rich brat Francis (Mark Holton), except that Pee-wee follows a dubious fortune teller's advice to hunt for it in the Alamo. Cue a road-trip, where we learn, if the opening sequence in Pee-wee's buoyantly daffy hometown hasn't made it clear, that nobody in this universe, nor any of the events which transpire within it, have any particular connection to reality. Illogic governs everything about this story, and yet it's a rigidly consistent and disciplined illogic that makes all the sense in the world if you were yourself 8-years-old at one point, and especially if you were an 8-year-old who watched the same Bugs Bunny cartoons that the writers did.

This whole-hearted embrace of the mentality of a young boy (definitely a boy: the fact that it's structured as a love story about a bike, complete with an "eww, girls!" subplot that bookends the movie, makes that crystal clear) is both the film's great point of distinction, and after a certain while it's main liability; there's only so far you can take a plot whose entire point is to have the hopscotching, addled rhythm of a distracted child, and Pee-wee's Big Adventure does end up with a really bad, and almost certainly unavoidable case of Episodic Structure; it never builds up to anything, because it never can build up to anything, just play out events one after another until eventually there's been enough running time that the bike chase through the Warner studio lot that was Reubens's first idea for the story can be presented. Growth or lessons learned would be a violation of the movie's concept (though the final story beat suggests that some growth is okay, as long as it doesn't have actual onscreen ramifications).

I do not want to go so far as to say that the film is boring: Reubens's manic performance and Burton's high-speed direction and primary-color visuals prohibit that. But limited, maybe, and while it is delightful, it's also very same-ey in the ways that its delightful, at least until the studio chase. There's a reason the cartoons that inspired its storytelling were all between six and eight minutes long.

Minimally, the film is never anything less than distinctive: the candy-colored kitsch style that dominates it wasn't really picked up by anyone after Burton jumped feet-first into his more characteristic Expressionist mode with Beetlejuice, and so it still looks as pointedly original as would have been the case a quarter-century ago, with the caveat that the '80s-ness of it all has gotten extraordinarily pronounced as the years go by, and so we could never go so far as to call it "fresh". Its charms, in whatever measure they exist, remain potent still, and while it's a small classic at best, and that largely with the aid of nostalgia, it's got a mountain of personality, which more than justifies it in the face of whatever shortcomings dog it.

The chief attraction of the 1985 film Pee-wee's Big Adventure since sometime early in the 1990s has been that it was the first feature directed by Tim Burton. But this was not always the case: in 1985 itself, for example, Tim Burton was known, if at all, by a small and self-selective audience of animation fans who would know him only for the stop-motion short Vincent that he was allowed to direct during his unhappy stay at Walt Disney Animation. At that time, of course, the more obvious point of appeal would have been...

Well, that's the hell of it. Look at it from any angle you want, but Pee-wee's Big Adventure is a stupefyingly weird idea for a movie: the character of Pee-wee Herman, created by stand-up comic and Groundlings member Paul Reubens in the late '70s, had been the centerpiece of a midnight stage show in Los Angeles that was hugely successful as midnight stage shows go, getting the actor some nationwide prominence on TV chat shows, but that's a limited sort of fame at best. And yet, Pee-wee's Big Adventure was greenlit by Warner Bros. on the strength of literally no script at all, just the studio's faith that Reubens would be able to deliver something of merit. Even weirder: it worked. The film made back its $6 million budget more than six times over, inspiring the creation of a TV show based around Reubens' character, Pee-wee's Playhouse, which was enough to make the nasal man-child one of the biggest pop culture figures in America in the back half of the 1980s (we had some really fucking weird pop culture back in the 1980s - a bull terrier hawking beer was almost as big in those days as Pee-wee was). It also set Burton on the very fast, very short track that ended with the huge-budget blockbuster Batman four years and two movies later. Happy endings for everybody, then!

Looking back with years of Burton steadily making himself a household name and then a brand, there's not all that much of the "Burtonesque" to Pee-wee's Big Adventure outside of a few scenes, chief among them a nightmare involving abnormally freakish clowns performing surgery on a bicycle in an environment made up of neon tubes and canted surfaces covered in a black-and-white checkerboard pattern, and a strange hitchhiker lady whose face explodes in some kind of family-friendly, PG-rated body horror that was the main reason I did not watch this film even a single time between the time it scared the ever-loving shit out of me when I was 7 and sometime in my early 20s. Outside of this, there is nothing of the way that his earlier shorts, Vincent and Frankenweenie, speak to the aesthetic he'd so assiduously cultivate, or that even his sophomore feature, Beetlejuice, looks for all the world like the movies he'd still be making 15 and 20 years down the road. And yet, Burton was an inspired choice to direct, maybe the best choice in the mid-'80s, because Pee-wee Herman as a concept is basically a cartoon character - Reubens's flexible, rubbery voice alone would drive us to that conclusion - and the wall-to-wall wackiness that makes up Pee-wee's Big Adventure is cartoon logic through and through. And the thing about Tim Burton that is easy to forget, is that he was by training, at the beginning of his career, an animator, something that's obvious from the first moments of the film and never lets up. It's not quite as formally bracing as when Looney Tunes director Frank Tashlin started applying the visual storytelling of the animated comic short to live-action features in the '40s and '50s, but Pee-wee's Big Adventure is chiefly successful because of its commitment to an artistic ideal: make something that looks, talks, feels, and moves like a cartoon.

A lot of that has to do with Reubens himself, of course, whose physical immersion into the Pee-wee Herman role is almost terrifying in its enthusiasm. And a lot, as well, owes to composer Danny Elfman, writing only his second film score, the first for a movie not written and directed by his brother: the Oingo Boingo singer, hired by Burton on a profoundly lucky whim, is the film's rather obvious secret weapon, laying a musical foundation for all the warped activities that bounces and sidles around crazily, owing a clear debt to Nino Rota's music for 8½, but bent around and jazzed up like a meth binge. Burton himself supplies a searingly bright color palette and a perfectly-aimed visual sense of humor.

Above and beyond all this, though, the film's screenplay is just right for the movie it wants to be: concocted by Reubens with fellow Groundling Phil Hartman, and Michael Varhol, it starts off by posting an impossible character - a grown man with the emotional maturity of an 8-year-old who nevertheless functions as an entirely self-sufficient, well-liked member of his community - and a ridiculous scenario, in which Pee-wee's beloved bike (the kind with pedals, not the kind with a motor in it) is stolen by fellow man-child and rich brat Francis (Mark Holton), except that Pee-wee follows a dubious fortune teller's advice to hunt for it in the Alamo. Cue a road-trip, where we learn, if the opening sequence in Pee-wee's buoyantly daffy hometown hasn't made it clear, that nobody in this universe, nor any of the events which transpire within it, have any particular connection to reality. Illogic governs everything about this story, and yet it's a rigidly consistent and disciplined illogic that makes all the sense in the world if you were yourself 8-years-old at one point, and especially if you were an 8-year-old who watched the same Bugs Bunny cartoons that the writers did.

This whole-hearted embrace of the mentality of a young boy (definitely a boy: the fact that it's structured as a love story about a bike, complete with an "eww, girls!" subplot that bookends the movie, makes that crystal clear) is both the film's great point of distinction, and after a certain while it's main liability; there's only so far you can take a plot whose entire point is to have the hopscotching, addled rhythm of a distracted child, and Pee-wee's Big Adventure does end up with a really bad, and almost certainly unavoidable case of Episodic Structure; it never builds up to anything, because it never can build up to anything, just play out events one after another until eventually there's been enough running time that the bike chase through the Warner studio lot that was Reubens's first idea for the story can be presented. Growth or lessons learned would be a violation of the movie's concept (though the final story beat suggests that some growth is okay, as long as it doesn't have actual onscreen ramifications).

I do not want to go so far as to say that the film is boring: Reubens's manic performance and Burton's high-speed direction and primary-color visuals prohibit that. But limited, maybe, and while it is delightful, it's also very same-ey in the ways that its delightful, at least until the studio chase. There's a reason the cartoons that inspired its storytelling were all between six and eight minutes long.

Minimally, the film is never anything less than distinctive: the candy-colored kitsch style that dominates it wasn't really picked up by anyone after Burton jumped feet-first into his more characteristic Expressionist mode with Beetlejuice, and so it still looks as pointedly original as would have been the case a quarter-century ago, with the caveat that the '80s-ness of it all has gotten extraordinarily pronounced as the years go by, and so we could never go so far as to call it "fresh". Its charms, in whatever measure they exist, remain potent still, and while it's a small classic at best, and that largely with the aid of nostalgia, it's got a mountain of personality, which more than justifies it in the face of whatever shortcomings dog it.