Blockbuster History: Animals that have lost their way

Every Sunday this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: after this many entries in their surprisingly durable franchise, the zoo animals of Madagascar 3: Europe's Most Wanted are perhaps the most prominent of all dislocated movie critters. But not the first, not at all, and some of them don't even take an endless franchise to get home, managing the feat in the tidy span of a single feature.

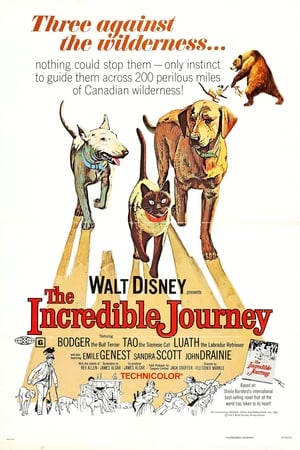

There's a fairly smart, artistically bold feature hiding inside the Walt Disney Company's 1963 adventure movie The Incredible Journey, and finding it takes virtually no effort whatsoever. All you have to do is remove the narration. See, The Incredible Journey is about three domestic pets - an aging bull terrier named Bodger, a much more youthful Labrador retriever named Luath, and a Siamese cat named Tao - who proceed with an intensity of purpose rare in non-sentient quadrupeds across some 250 miles of Canadian forests, fields, and mountains in order to find their way back home to their owners. The reason they are not presently with their owners is a little convoluted and involves a vacation plus a hunting trip plus various stupidities on the part of both humans and non-humans, and need not concern us here. All that matters is that the film concerns two dogs and a cat traversing Canada, en route to a super-cutesy reunion with their family, replete with two unendurably darling children of the sort favored by middle-aged people who like the idea of children more than the actual fact of children themselves.

And all of this is staged with remarkable sophistication by director Fletcher Markle, a TV veteran plucked up for no obvious reason, who never afterwards made a theatrical feature in his career; and yet he coaxed such amazing "performances" out of his animals - or better to say, maybe, that he figured out the best possible place to set the camera while highly-skilled animal trainers got the stars to behave in ways that look for all the world like acting - that it seems a damn shame he never really got to do anything else of note. The Incredible Journey is a shockingly good triumph of a very narrow kind of filmmaking triumph: it depicts three animals in a manner that never once in 80 minutes asks them to stop being animals, and also manages to suggest that each of them has the very specific, functionally anthropomorphic personality given to them by the script (adapted by producer James Algar, maven of Disney's True-Life Adventures documentary series, from Sheila Burnford's novel), and observes all three of the stars doing things that, in the normal course of their lives, we would not expect to see a dog or cat do. It is a story that has a clear, crisp rise in its action and development of its dramatic stakes, all while playing completely fair by its central premise, that these dogs and this cat are exactly like the dogs and cats you or I might have in our very own home, and not like the talking animals of even the most vigorously realistic cartoon animal picture, say; Disney's own Lady and the Tramp catapults to the forefront of one's mind.

This was not the first nor the last time such a thing would be done, but it's extravagantly damn rare, and Markle, though he may well have been a hack with no real interest in art or doing anything but cashing a paycheck, did right by the concept: he treated those animals like real honest-to-God movie actors, giving them the same kind of shot set-ups that you would to a person, only scaled down. Though every last inch of it is faked, there's a purity and honesty to the film in that respect, at least, and that respect matters a great deal.

So clear and driven and direct is Markle's direction that The Incredible Journey functions extraordinarily well as a silent movie, with the expressions on the dogs faces (the cat's less so; all cats are by nature inscrutable, Siamese cats more than most) conveying a great deal of narrative information - yes, the expressions on the dogs' faces, I know how idiotic that is to say - and the skillful manipulation of shots filling in the rest (editor Norman Palmer, another True-Life Adventure vet, performed some very special voodoo in putting this movie together; many films exploit the Kuleshov Effect, where the viewer assumes a relationship between shots and creates the narrative linking them subconsciously, but The Incredible Journey is very little else besides the Kuleshov Effect puttering away madly for almost an hour and a half). The visual storytelling is subtle and precise; for a cheap Disney programmer, it's a magnificent achievement of craftsmanship.

And the whole thing is covered in virtually non-stop narration, from the warm twang of a certain Rex Allen, and it is insufferable.

Here's a catch-22 for you to play around with, if you want: The Incredible Journey is one single choice away from being a really nervy experiment in telling a complete story with almost no dialogue and three protagonists who are literally inhuman, and if it had been given a chance to be that thing, it might very well have been an experimental gem hiding inside a mainstream family adventure. But it's only because it is a mainstream family adventure, made under the imprimatur of the singularly commercially-minded Walt Disney no less, it's fair to say that the reason the movie exists at all is because it could be turned into something conversational and easy to follow, like a storybook at bedtime. In short: the movie could have been really great without narration, but without narration it's unlikely that the movie would have been made.

Thus it is, instead of a brassy formal exercise in making a movie with animal protagonists, we have a sticky-sweet kids' movie. And as a sticky-sweet kids' movie, it is surely not without charm; viewed from nearly a half-century of evolution that has found entertainment for children becoming ever louder, faster, busier, and more fascinated by feces and flatulence, there's something unabashedly likable about a movie as outright laconic as The Incredible Journey, which ambles along without ever making it seem like anything genuinely bad could ever happen to Bodger, Luath, and Tao - Allen's genial tone of voice makes damn sure that this remains the case - and never hypes up the dramatic stakes beyond "Then, this minor inconvenience happened to the pets. Aw, shucks. But they went on ahead and muscled through." It's almost terrifying how relaxed and consequence-free the narrative is, a pleasing yarn instead of a gripping tale. All of this was meant for five-year-olds in the '60s, and that means that the film has to be readily accessible and manifestly un-traumatising, and if that means that a 2010s child would be bored senseless - which I regretfully suspect would be the case - or that a 2010s film blogger would grouse about how aggressively the film fails to be an alienating formal exercise, well, Disney and Markle and Algar weren't looking that far ahead.

Anyway, there's still the saving grace that the animals are allowed to be animals, and thus retain their dignity. Talking animal pictures are a sucking hole of depravity - Babe is not masterpiece enough to stand against its entire fetid subgenre - and The Incredible Journey was itself remade into just such a monstrosity 30 years later, under the title Homeward Bound: The Incredible Journey, complete with Michael J. Fox, Sally Field, and Don Ameche providing the animals' voices. The 1963 movie might be pandering as all hell in its constant narration, spelling out every last single event as though the viewer is literally not looking at the screen, and it might have all the dramatic urgency of watching the sun set on an autumn day with a pitcher of iced tea to keep you company, but it's not shrill and zany and self-conscious, and it comes from a place that genuinely respects and loves dogs for being dogs and cats for being cats. It is an animal movie for people who think of their pets as actual pets and not wee people in furry costumes, and that is more than enough to keep it from being a lost, nostalgic curiosity, even if that's perhaps the only thing that it really has going for it.

There's a fairly smart, artistically bold feature hiding inside the Walt Disney Company's 1963 adventure movie The Incredible Journey, and finding it takes virtually no effort whatsoever. All you have to do is remove the narration. See, The Incredible Journey is about three domestic pets - an aging bull terrier named Bodger, a much more youthful Labrador retriever named Luath, and a Siamese cat named Tao - who proceed with an intensity of purpose rare in non-sentient quadrupeds across some 250 miles of Canadian forests, fields, and mountains in order to find their way back home to their owners. The reason they are not presently with their owners is a little convoluted and involves a vacation plus a hunting trip plus various stupidities on the part of both humans and non-humans, and need not concern us here. All that matters is that the film concerns two dogs and a cat traversing Canada, en route to a super-cutesy reunion with their family, replete with two unendurably darling children of the sort favored by middle-aged people who like the idea of children more than the actual fact of children themselves.

And all of this is staged with remarkable sophistication by director Fletcher Markle, a TV veteran plucked up for no obvious reason, who never afterwards made a theatrical feature in his career; and yet he coaxed such amazing "performances" out of his animals - or better to say, maybe, that he figured out the best possible place to set the camera while highly-skilled animal trainers got the stars to behave in ways that look for all the world like acting - that it seems a damn shame he never really got to do anything else of note. The Incredible Journey is a shockingly good triumph of a very narrow kind of filmmaking triumph: it depicts three animals in a manner that never once in 80 minutes asks them to stop being animals, and also manages to suggest that each of them has the very specific, functionally anthropomorphic personality given to them by the script (adapted by producer James Algar, maven of Disney's True-Life Adventures documentary series, from Sheila Burnford's novel), and observes all three of the stars doing things that, in the normal course of their lives, we would not expect to see a dog or cat do. It is a story that has a clear, crisp rise in its action and development of its dramatic stakes, all while playing completely fair by its central premise, that these dogs and this cat are exactly like the dogs and cats you or I might have in our very own home, and not like the talking animals of even the most vigorously realistic cartoon animal picture, say; Disney's own Lady and the Tramp catapults to the forefront of one's mind.

This was not the first nor the last time such a thing would be done, but it's extravagantly damn rare, and Markle, though he may well have been a hack with no real interest in art or doing anything but cashing a paycheck, did right by the concept: he treated those animals like real honest-to-God movie actors, giving them the same kind of shot set-ups that you would to a person, only scaled down. Though every last inch of it is faked, there's a purity and honesty to the film in that respect, at least, and that respect matters a great deal.

So clear and driven and direct is Markle's direction that The Incredible Journey functions extraordinarily well as a silent movie, with the expressions on the dogs faces (the cat's less so; all cats are by nature inscrutable, Siamese cats more than most) conveying a great deal of narrative information - yes, the expressions on the dogs' faces, I know how idiotic that is to say - and the skillful manipulation of shots filling in the rest (editor Norman Palmer, another True-Life Adventure vet, performed some very special voodoo in putting this movie together; many films exploit the Kuleshov Effect, where the viewer assumes a relationship between shots and creates the narrative linking them subconsciously, but The Incredible Journey is very little else besides the Kuleshov Effect puttering away madly for almost an hour and a half). The visual storytelling is subtle and precise; for a cheap Disney programmer, it's a magnificent achievement of craftsmanship.

And the whole thing is covered in virtually non-stop narration, from the warm twang of a certain Rex Allen, and it is insufferable.

Here's a catch-22 for you to play around with, if you want: The Incredible Journey is one single choice away from being a really nervy experiment in telling a complete story with almost no dialogue and three protagonists who are literally inhuman, and if it had been given a chance to be that thing, it might very well have been an experimental gem hiding inside a mainstream family adventure. But it's only because it is a mainstream family adventure, made under the imprimatur of the singularly commercially-minded Walt Disney no less, it's fair to say that the reason the movie exists at all is because it could be turned into something conversational and easy to follow, like a storybook at bedtime. In short: the movie could have been really great without narration, but without narration it's unlikely that the movie would have been made.

Thus it is, instead of a brassy formal exercise in making a movie with animal protagonists, we have a sticky-sweet kids' movie. And as a sticky-sweet kids' movie, it is surely not without charm; viewed from nearly a half-century of evolution that has found entertainment for children becoming ever louder, faster, busier, and more fascinated by feces and flatulence, there's something unabashedly likable about a movie as outright laconic as The Incredible Journey, which ambles along without ever making it seem like anything genuinely bad could ever happen to Bodger, Luath, and Tao - Allen's genial tone of voice makes damn sure that this remains the case - and never hypes up the dramatic stakes beyond "Then, this minor inconvenience happened to the pets. Aw, shucks. But they went on ahead and muscled through." It's almost terrifying how relaxed and consequence-free the narrative is, a pleasing yarn instead of a gripping tale. All of this was meant for five-year-olds in the '60s, and that means that the film has to be readily accessible and manifestly un-traumatising, and if that means that a 2010s child would be bored senseless - which I regretfully suspect would be the case - or that a 2010s film blogger would grouse about how aggressively the film fails to be an alienating formal exercise, well, Disney and Markle and Algar weren't looking that far ahead.

Anyway, there's still the saving grace that the animals are allowed to be animals, and thus retain their dignity. Talking animal pictures are a sucking hole of depravity - Babe is not masterpiece enough to stand against its entire fetid subgenre - and The Incredible Journey was itself remade into just such a monstrosity 30 years later, under the title Homeward Bound: The Incredible Journey, complete with Michael J. Fox, Sally Field, and Don Ameche providing the animals' voices. The 1963 movie might be pandering as all hell in its constant narration, spelling out every last single event as though the viewer is literally not looking at the screen, and it might have all the dramatic urgency of watching the sun set on an autumn day with a pitcher of iced tea to keep you company, but it's not shrill and zany and self-conscious, and it comes from a place that genuinely respects and loves dogs for being dogs and cats for being cats. It is an animal movie for people who think of their pets as actual pets and not wee people in furry costumes, and that is more than enough to keep it from being a lost, nostalgic curiosity, even if that's perhaps the only thing that it really has going for it.