Year Of Blood: She says she knows about jokes, this time the joke is on me

I'm tired of blogging. It takes hours, and I have to watch shitty movies, and I never get any money for it, so this is going to be my last essay ever.

NO! I'm lying, because it is April 1st! Haha.

I am really bad at April Fool's jokes. But at least I've never killed anybody.

1986 - an infamous time in horror movie history. The slasher boom of the early 1980s had more or less completely curdled by this point, but nobody had come up with anything to replace the long played-out template since Wes Craven's slasher/ghost hybrid A Nightmare on Elm Street, which had very little influence beyond initiating the replacement of tired stories about sexually neurotic psycho killers with tired stories about sexually neurotic psycho killer monsters.

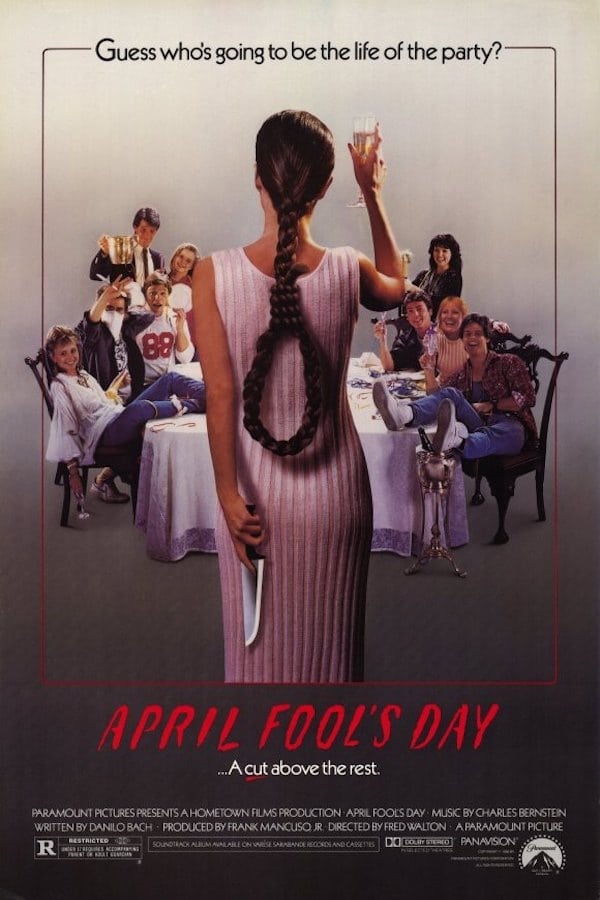

And yet, in despite of this widespread creative anemia, if not indeed because of it, 1986 produced two of the best - or at least, most idiosyncratic - American horror films made in the back half of the 1980s (three, if we feel up for including Chopping Mall). One of these is The Hitcher, which I really ought to get around to reviewing some time, because there's a real possibility it's my favorite non-Italian horror movie of the decade. The other is April Fool's Day, one of the savviest examples of slasher film self-commentary in existence, beating Scream by a cool ten years and a half. It says quite a lot at how ingenious the movie is that I can't quite figure out what to call it, even; a parody without jokes, maybe, a movie so stone-faced and unblinking in its satiric aggression against the subgenre that until it pulls back the curtain in the second-to-last scene and tells you what it's been doing all along, there's really not even any reason to regard it as anything at all but a wholly straightforward example of the form, with snappier, smarter writing (Boswell's Life of Johnson and Ibsen's Ghosts are name-dropped) and considerably better acting than most other slashers.

Then again, the title is April Fool's Day, which might have been all the tell that an especially sophisticated viewer would have needed.

And, going back and looking at it with the eye of a seasoned viewer, there are some things that seem off. Sure, it's a Paramount Pictures film - home of good old Jason Voorhees himself, releasing the dire Friday the 13th, Part VI: Jason Lives later in the same year - but the very first shot is a first-person interview shot on video, an off-kilter opening gambit that already has introduced a touch of unpredictability and confusion into the first scene; "confusion", because as it turns out, the girl being interviewed is lying and playing up to the camera anyway.

Soon enough, we jump back to find ourselves in a group of young people waiting at a ferry dock, and it is a sign of how quietly intelligent Danilo Bach's screenplay is (I'm sorry, Oscar-nominated screenwriter Danilo Bach, for his only previous work, Beverly Hills Cop) that I was able to keep track of every character in a nine-person pool of Expendable Meat, by name, from the 15-minute mark onward; compared to movies that don't bother to name some characters until after they are dead, this is an expository triumph of the first order. For the record, we have Nikki (Deborah Goodrich), the somewhat brittle and entitled Rich Bitch who was being intereviewed (and yet even as the Rich Bitch, she has more shading than the stock slasher character usually receives); Kit (Amy Steel, of Friday the 13th, Part 2), a much friendlier girl, but a bit of a wet hen; Kit's boyfriend Rob (Ken Olandt), who has the least personality of the whole cast; Chaz (Clayton Rohner), a sort of oily rocker type; Arch (Thomas F. Wilson, immortalised the previous year as Biff in Back to the Future), a stocky frat-boy meathead (he and Chaz are weirdly okay with pretending to be gay lovers for douchey college boys in a 1980s movie) - these are the core of friends, who don't quite know what to make of three newbies. Those being Nan (Leah King Pinsent), a quiet and bookish girl given to making "look at my freshman education!" literary references; Harvey (Jay Baker), who prefers "Hal", though nobody calls him that, a gland-handling rich Southerner; and Skip (Griffin O'Neal), the previously unmentioned cousin of the woman hosting the party to which this diverse set of college students. That woman, we pick up, is a certain Muffy St. John (Deborah Foreman), the heiress to an island and the huge manor house thereon, and for the reasons of her wealthy and unendurably WASPy name, we obviously expect her to be an airy Queen Rich Bitch of the highest order. But that's not the case, when we cut over to the island where she is still alone, to meet her; she's a bit addled, in fact, and has an apparent April Fool's prank-related trauma in her youth, which is perhaps the reason that she has gathered everyone together for a weekend party heavy on practical joking.

The jokes start off before the ferry even leaves the mainland for the island (and if you suppose that the ferryman, played by Lloyd Berry, makes a point of mentioning that this is the very last ferry run for the next three days, and the kids will be hereafter isolated, I salute your grasp of the self-evident), with Chaz and Arch in particular living down to our immediate assumptions of their stock characters by making jokes about flies being open, and faking a death, and being the sort of charmers that you can't wait to see die violently. As a matter of fact, April Fool's Day has an unusually well-stocked cast of annoying twerps and assorted douchebags, though they are exceptionally well-written and natty twerps and douches - Nikki gets the absolutely killer line, "On a clear day, you can see the Kennedys", registering both her envy and disgust at Muffy's age-inappropriate wealth. This turns out to be part of the movie's strategy: ramp up the stock characters and stock situations, playing on our knowledge of how slasher movies do what they do and expecting us to start connecting the dots in advance. You can barely find a latter-day review of April Fool's Day that doesn't use a variant of the phrase "a slasher movie for people who hate slasher movies", and I think that has something to do with the conspicuous lack of gore or blood, and the way that the ending subverts the expectations we bring to the table regarding slashers, but I don't think I buy it. Scream, a mocking, smugly hip parody that wears its satire on its sleeve, is a slasher movie for people who hate slasher movies. April Fool's Day really does work best, I think, when it's situated firmly in the context of 1986 and the kind of slasher movies that had been produced by the carload for the prior six years; it's a slasher movie for people who are absolute maniacs for slasher movies, that is, although those people tend to be awfully unforgiving about being made the butt of a joke. But again: the title! There's no reason to expect anything else than a good solid punking.

Back to the movie, though it mostly writes itself: there's an accident that leaves us with the ideal disgruntled and newly-disfigured old man (Mike Nomad) with the perfect motive to go hunting irresponsible young people, while on Muffy Island, the various folks drift off in the way of people who all have one friend in common but don't really gel with each other; they find in the process that Muffy has booby-trapped their bedrooms with practical jokes that cut rather nastily close to the bone in some cases. It leaves most of the party in a sour enough mood that nobody quite notices the next morning that Skip isn't around; we, though, have a fairly good idea that something dreadful has happened, given that we last saw him very drunk and very angry at the world and Muffy in particular, and very unaware of the shadowy figure stalking him all the way to the boathouse in the woods surrounding the manor. It's only when Kit and Rob go off to fuck in the same boathouse - they fuck a lot, making it a nice, and characteristically subtle subversion when they turn out to be the Final Couple - that Skip's pale, dessicated body is discovered, though it has quite unsurprisingly gone missing when the other six partiers show up.

This is right about the half-way point of a nice, snug 89-minute film, and the rest of the running time is given over to mystery-solving: people running around the island trying to find a killer or evidence of bodies, and then going missing and adding to the pile of missing corpses. Meanwhile, Muffy is acting so transparently guilty that we all figure out that something else must obviously be going on, though it takes a lot of murders until anybody figures out what that is.

Boilerplate stuff, though it's done awfully well: there's not a weak performance in the batch, with Foreman's ambiguous murderess as the clear standout (I also rather liked Pinsent and was sorry she was among the first to go; the men are weaker on the whole, though I admired Baker's performance of Harvey quite a lot, maybe the cleanest satire of Reagan-era rich adolescent venality in the film), and Bach's screenplay is a miracle of understatement, letting us figure out plot points for ourselves (for example, there's an abortion in one character's backstory, and a fatal car crash in another's, and the filmmakers trust us enough to figure this out without a big thing being made of it), and the way it's pieced together by director Fred Walton looks awfully like every other post-'84 slasher movie, though in retrospect it's frequently nothing less than amazing how perfect the editing and camera work together to misdirect the viewer in key places.

It's well ahead of the curve for effective, intelligent slashers, then, in despite of its intense sqeuamishness about gore, and that's when we get to the twist. There's no way to not discuss it, and I don't want to spoil it for a soul: I, myself, was taken in by it, and while I'm not in the habit of deliberately trying to outguess mysteries, I think the movie does a good job of keeping us in the dark. So if you haven't seen the film, I beg you not to peek behind the spoiler bars, and I hope the rest of you don't mind the inconvenience. Now, the complaint that is levied by some is that April Fool's Day is, after all, a slasher film without a single death; and that does seem to be a bit like a dirty trick. But it's sort of ingenious, in the way it makes this, effectively, The Sting of slasher movies: we're so distracted with how the characters are treating each other, we don't stop to think that the movie is doing the same thing to us. One thing worth observing, straight out: the movie isn't absolutely fair about its twist. I shall readily admit that there's not a single moment, on reflection, where it lies: the editing and the otherwise-inexplicable lack of gore make sure of that. It does, however, play fast and loose with human psychology: surely, out of the six people who are stalked and caught by Muffy, and then informed that they've been part of an elaborate trick, one of them would have been angry enough to blow the whole thing apart, right? And even if that's not the case, some of them - especially Nikki, who I'd think would be the hardest one to convince, anyway - would barely have enough time to grasp what was happening and agree to play along.

And then, there's the matter of whether this makes any sense in the first place: Muffy's explanation is shockingly coherent, for a twist-based movie, but if the point was to test the validity of her murder-mystery weekend scenario, wouldn't the more authentic test be to tell everyone what was going on beforehand? Of course people are going to find it more thrilling if they think they're actually in danger of being murdered! The only possible answer is that Muffy is just really that meanspirited - which the abortion tape certainly suggests is a real possibility - but that brings us back to the question of why every single one of her victims agreed to play along.

I'm also really damn confused what the final scene is all about: it's the most egregious example of many in which a scene is played for the audience's benefit, rather than the characters' - surely Muffy could tell the difference between having her throat slit and having a prop knife squirting prop blood onto her skin, which makes her look of pain and fear absolutely inexplicable. Besides the which, it's just paying off the early flashback scene that the movie has done absolutely nothing useful with to this point, anyway.

That doesn't change the fact that in the aggregate, April Fool's Day is a profoundly smart trick on the audience, using the very obviousness and predictability of the slasher films it looks just like - again, an oddly literate slasher movie, and one that's well-acted, but it still hews quite closely to the most formulaic structure - first to lull the viewer into stupidity, then to surprise and either delight or outrage the viewer, and only in retrospect draw our attention to how the whole affair only works as well as it does because slasher films are so stupid and predictable. This a world away from Scream being dumb as a box of rocks and then pretending that it's smart by having all the characters talk about how dumb it is. This is revealing the bankruptcy of the slasher in 1986 by wallowing in its most ludicrous, obvious pandering, and then revealing that it was not either ludicrous or obvious in the way we expected, and indeed laughing at our gullibility and the insipidity of the movies that led us to that point. It's not hard to see how this could infuriated and alienate exactly the people best-equipped to find April Fool's Day ingenious; particularly since the moment of the reveal is, itself, the most effectively scary part of the film, with Kit's disorientation rendered by showing all of the "victims" talking without sound. And, of course, it's only scary because we're just as slow on the uptake as Kit. This is, again, making fun of the viewer, and it's not very nice; but practical jokes aren't nice, and there's no reason not to be a good sport about this particular one.

All of this can't hide the one fact that April Fool's Day is, at heart, a gimmick. A sublimely executed one. And there are plenty of moments that rank among the best touches in American slasher history: the giallo-esque discovery of dolls mimicking the dead bodies; the room of silent conversations that I mentioned in the spoiler-bar part, for y'all who hung out in the spoiler-free text; the glimpses of Skip's white body beneath the slats of the boathouse floor; the painting with moving eyes, which isn't even as unnerving as the same painting with blank eyeholes. But it still feels a lot like a machine, however elegant that machine undoubtedly is, somewhat in the way that lesser Hitchcock films (though still Hitchcock films) are a bit more about technique than entertainment. I'm still terrifically pleased by the movie, and nothing can take the sizzle out of the best lines of dialogue, but it is what it is: the cleverness that is its best point of distinction ends up limiting it somewhat as a horror film for the 76 minutes before that cleverness is really made manifest.

Body Count: 7 or thereabouts; the twistiness of the plot makes it awfully hard to say outright.

April Fool's Pranks: 13, counting all of the "your fly is open" tricks as one.

NO! I'm lying, because it is April 1st! Haha.

I am really bad at April Fool's jokes. But at least I've never killed anybody.

1986 - an infamous time in horror movie history. The slasher boom of the early 1980s had more or less completely curdled by this point, but nobody had come up with anything to replace the long played-out template since Wes Craven's slasher/ghost hybrid A Nightmare on Elm Street, which had very little influence beyond initiating the replacement of tired stories about sexually neurotic psycho killers with tired stories about sexually neurotic psycho killer monsters.

And yet, in despite of this widespread creative anemia, if not indeed because of it, 1986 produced two of the best - or at least, most idiosyncratic - American horror films made in the back half of the 1980s (three, if we feel up for including Chopping Mall). One of these is The Hitcher, which I really ought to get around to reviewing some time, because there's a real possibility it's my favorite non-Italian horror movie of the decade. The other is April Fool's Day, one of the savviest examples of slasher film self-commentary in existence, beating Scream by a cool ten years and a half. It says quite a lot at how ingenious the movie is that I can't quite figure out what to call it, even; a parody without jokes, maybe, a movie so stone-faced and unblinking in its satiric aggression against the subgenre that until it pulls back the curtain in the second-to-last scene and tells you what it's been doing all along, there's really not even any reason to regard it as anything at all but a wholly straightforward example of the form, with snappier, smarter writing (Boswell's Life of Johnson and Ibsen's Ghosts are name-dropped) and considerably better acting than most other slashers.

Then again, the title is April Fool's Day, which might have been all the tell that an especially sophisticated viewer would have needed.

And, going back and looking at it with the eye of a seasoned viewer, there are some things that seem off. Sure, it's a Paramount Pictures film - home of good old Jason Voorhees himself, releasing the dire Friday the 13th, Part VI: Jason Lives later in the same year - but the very first shot is a first-person interview shot on video, an off-kilter opening gambit that already has introduced a touch of unpredictability and confusion into the first scene; "confusion", because as it turns out, the girl being interviewed is lying and playing up to the camera anyway.

Soon enough, we jump back to find ourselves in a group of young people waiting at a ferry dock, and it is a sign of how quietly intelligent Danilo Bach's screenplay is (I'm sorry, Oscar-nominated screenwriter Danilo Bach, for his only previous work, Beverly Hills Cop) that I was able to keep track of every character in a nine-person pool of Expendable Meat, by name, from the 15-minute mark onward; compared to movies that don't bother to name some characters until after they are dead, this is an expository triumph of the first order. For the record, we have Nikki (Deborah Goodrich), the somewhat brittle and entitled Rich Bitch who was being intereviewed (and yet even as the Rich Bitch, she has more shading than the stock slasher character usually receives); Kit (Amy Steel, of Friday the 13th, Part 2), a much friendlier girl, but a bit of a wet hen; Kit's boyfriend Rob (Ken Olandt), who has the least personality of the whole cast; Chaz (Clayton Rohner), a sort of oily rocker type; Arch (Thomas F. Wilson, immortalised the previous year as Biff in Back to the Future), a stocky frat-boy meathead (he and Chaz are weirdly okay with pretending to be gay lovers for douchey college boys in a 1980s movie) - these are the core of friends, who don't quite know what to make of three newbies. Those being Nan (Leah King Pinsent), a quiet and bookish girl given to making "look at my freshman education!" literary references; Harvey (Jay Baker), who prefers "Hal", though nobody calls him that, a gland-handling rich Southerner; and Skip (Griffin O'Neal), the previously unmentioned cousin of the woman hosting the party to which this diverse set of college students. That woman, we pick up, is a certain Muffy St. John (Deborah Foreman), the heiress to an island and the huge manor house thereon, and for the reasons of her wealthy and unendurably WASPy name, we obviously expect her to be an airy Queen Rich Bitch of the highest order. But that's not the case, when we cut over to the island where she is still alone, to meet her; she's a bit addled, in fact, and has an apparent April Fool's prank-related trauma in her youth, which is perhaps the reason that she has gathered everyone together for a weekend party heavy on practical joking.

The jokes start off before the ferry even leaves the mainland for the island (and if you suppose that the ferryman, played by Lloyd Berry, makes a point of mentioning that this is the very last ferry run for the next three days, and the kids will be hereafter isolated, I salute your grasp of the self-evident), with Chaz and Arch in particular living down to our immediate assumptions of their stock characters by making jokes about flies being open, and faking a death, and being the sort of charmers that you can't wait to see die violently. As a matter of fact, April Fool's Day has an unusually well-stocked cast of annoying twerps and assorted douchebags, though they are exceptionally well-written and natty twerps and douches - Nikki gets the absolutely killer line, "On a clear day, you can see the Kennedys", registering both her envy and disgust at Muffy's age-inappropriate wealth. This turns out to be part of the movie's strategy: ramp up the stock characters and stock situations, playing on our knowledge of how slasher movies do what they do and expecting us to start connecting the dots in advance. You can barely find a latter-day review of April Fool's Day that doesn't use a variant of the phrase "a slasher movie for people who hate slasher movies", and I think that has something to do with the conspicuous lack of gore or blood, and the way that the ending subverts the expectations we bring to the table regarding slashers, but I don't think I buy it. Scream, a mocking, smugly hip parody that wears its satire on its sleeve, is a slasher movie for people who hate slasher movies. April Fool's Day really does work best, I think, when it's situated firmly in the context of 1986 and the kind of slasher movies that had been produced by the carload for the prior six years; it's a slasher movie for people who are absolute maniacs for slasher movies, that is, although those people tend to be awfully unforgiving about being made the butt of a joke. But again: the title! There's no reason to expect anything else than a good solid punking.

Back to the movie, though it mostly writes itself: there's an accident that leaves us with the ideal disgruntled and newly-disfigured old man (Mike Nomad) with the perfect motive to go hunting irresponsible young people, while on Muffy Island, the various folks drift off in the way of people who all have one friend in common but don't really gel with each other; they find in the process that Muffy has booby-trapped their bedrooms with practical jokes that cut rather nastily close to the bone in some cases. It leaves most of the party in a sour enough mood that nobody quite notices the next morning that Skip isn't around; we, though, have a fairly good idea that something dreadful has happened, given that we last saw him very drunk and very angry at the world and Muffy in particular, and very unaware of the shadowy figure stalking him all the way to the boathouse in the woods surrounding the manor. It's only when Kit and Rob go off to fuck in the same boathouse - they fuck a lot, making it a nice, and characteristically subtle subversion when they turn out to be the Final Couple - that Skip's pale, dessicated body is discovered, though it has quite unsurprisingly gone missing when the other six partiers show up.

This is right about the half-way point of a nice, snug 89-minute film, and the rest of the running time is given over to mystery-solving: people running around the island trying to find a killer or evidence of bodies, and then going missing and adding to the pile of missing corpses. Meanwhile, Muffy is acting so transparently guilty that we all figure out that something else must obviously be going on, though it takes a lot of murders until anybody figures out what that is.

Boilerplate stuff, though it's done awfully well: there's not a weak performance in the batch, with Foreman's ambiguous murderess as the clear standout (I also rather liked Pinsent and was sorry she was among the first to go; the men are weaker on the whole, though I admired Baker's performance of Harvey quite a lot, maybe the cleanest satire of Reagan-era rich adolescent venality in the film), and Bach's screenplay is a miracle of understatement, letting us figure out plot points for ourselves (for example, there's an abortion in one character's backstory, and a fatal car crash in another's, and the filmmakers trust us enough to figure this out without a big thing being made of it), and the way it's pieced together by director Fred Walton looks awfully like every other post-'84 slasher movie, though in retrospect it's frequently nothing less than amazing how perfect the editing and camera work together to misdirect the viewer in key places.

It's well ahead of the curve for effective, intelligent slashers, then, in despite of its intense sqeuamishness about gore, and that's when we get to the twist. There's no way to not discuss it, and I don't want to spoil it for a soul: I, myself, was taken in by it, and while I'm not in the habit of deliberately trying to outguess mysteries, I think the movie does a good job of keeping us in the dark. So if you haven't seen the film, I beg you not to peek behind the spoiler bars, and I hope the rest of you don't mind the inconvenience. Now, the complaint that is levied by some is that April Fool's Day is, after all, a slasher film without a single death; and that does seem to be a bit like a dirty trick. But it's sort of ingenious, in the way it makes this, effectively, The Sting of slasher movies: we're so distracted with how the characters are treating each other, we don't stop to think that the movie is doing the same thing to us. One thing worth observing, straight out: the movie isn't absolutely fair about its twist. I shall readily admit that there's not a single moment, on reflection, where it lies: the editing and the otherwise-inexplicable lack of gore make sure of that. It does, however, play fast and loose with human psychology: surely, out of the six people who are stalked and caught by Muffy, and then informed that they've been part of an elaborate trick, one of them would have been angry enough to blow the whole thing apart, right? And even if that's not the case, some of them - especially Nikki, who I'd think would be the hardest one to convince, anyway - would barely have enough time to grasp what was happening and agree to play along.

And then, there's the matter of whether this makes any sense in the first place: Muffy's explanation is shockingly coherent, for a twist-based movie, but if the point was to test the validity of her murder-mystery weekend scenario, wouldn't the more authentic test be to tell everyone what was going on beforehand? Of course people are going to find it more thrilling if they think they're actually in danger of being murdered! The only possible answer is that Muffy is just really that meanspirited - which the abortion tape certainly suggests is a real possibility - but that brings us back to the question of why every single one of her victims agreed to play along.

I'm also really damn confused what the final scene is all about: it's the most egregious example of many in which a scene is played for the audience's benefit, rather than the characters' - surely Muffy could tell the difference between having her throat slit and having a prop knife squirting prop blood onto her skin, which makes her look of pain and fear absolutely inexplicable. Besides the which, it's just paying off the early flashback scene that the movie has done absolutely nothing useful with to this point, anyway.

That doesn't change the fact that in the aggregate, April Fool's Day is a profoundly smart trick on the audience, using the very obviousness and predictability of the slasher films it looks just like - again, an oddly literate slasher movie, and one that's well-acted, but it still hews quite closely to the most formulaic structure - first to lull the viewer into stupidity, then to surprise and either delight or outrage the viewer, and only in retrospect draw our attention to how the whole affair only works as well as it does because slasher films are so stupid and predictable. This a world away from Scream being dumb as a box of rocks and then pretending that it's smart by having all the characters talk about how dumb it is. This is revealing the bankruptcy of the slasher in 1986 by wallowing in its most ludicrous, obvious pandering, and then revealing that it was not either ludicrous or obvious in the way we expected, and indeed laughing at our gullibility and the insipidity of the movies that led us to that point. It's not hard to see how this could infuriated and alienate exactly the people best-equipped to find April Fool's Day ingenious; particularly since the moment of the reveal is, itself, the most effectively scary part of the film, with Kit's disorientation rendered by showing all of the "victims" talking without sound. And, of course, it's only scary because we're just as slow on the uptake as Kit. This is, again, making fun of the viewer, and it's not very nice; but practical jokes aren't nice, and there's no reason not to be a good sport about this particular one.

All of this can't hide the one fact that April Fool's Day is, at heart, a gimmick. A sublimely executed one. And there are plenty of moments that rank among the best touches in American slasher history: the giallo-esque discovery of dolls mimicking the dead bodies; the room of silent conversations that I mentioned in the spoiler-bar part, for y'all who hung out in the spoiler-free text; the glimpses of Skip's white body beneath the slats of the boathouse floor; the painting with moving eyes, which isn't even as unnerving as the same painting with blank eyeholes. But it still feels a lot like a machine, however elegant that machine undoubtedly is, somewhat in the way that lesser Hitchcock films (though still Hitchcock films) are a bit more about technique than entertainment. I'm still terrifically pleased by the movie, and nothing can take the sizzle out of the best lines of dialogue, but it is what it is: the cleverness that is its best point of distinction ends up limiting it somewhat as a horror film for the 76 minutes before that cleverness is really made manifest.

Body Count: 7 or thereabouts; the twistiness of the plot makes it awfully hard to say outright.

April Fool's Pranks: 13, counting all of the "your fly is open" tricks as one.

Categories: horror, mysteries, parodies, slashers, year of blood