The films of Whit Stillman

A cluster of circumstances have made this the ideal moment to spring into an exceedingly low-key retrospective of an exceedingly low-key filmmaker: herewith, Mondays in April will be devoted to the films of one of America's most deliciously minor indie directors, Whit Stillman.

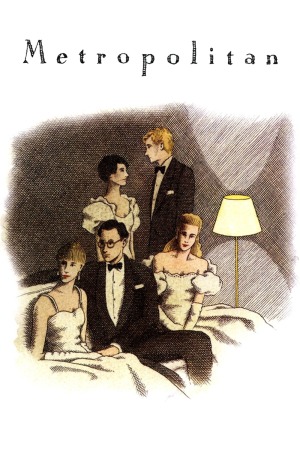

There are two terribly important, and tightly related things to know about Metropolitan: it was writer-director-producer Whit Stillman's very first movie, and it was released when Stillman was 38 years old. Aside from providing comfort to any aging wannabe filmmakers out there - you too can become a cause célèbre deep into adulthood! - it provides just exactly the right angle to understand exactly what is going on in a movie that is considerably sneakier and denser than it seems at first blush, not least because on close analysis, Metropolitan is, in fact, saying exactly what it appears to be saying, which means in theory that it's a very surfacey movie. The cunning bit is how on the obvious level, it's saying things in a flippant and ironic and heavily arch way, while with a little bit of digging, is saying those same ways in a far more thoughtful, humanist, and worldly way. It is the same division as that between the main characters - eight college students from upper class Manhattan backgrounds, over-educated and paralysed by too much thinking - and their creator, who despite having something of the same sociopolitical DNA, does not ultimately align himself with any of the youths, not even the one who comes closest to sharing his lapsed-into-middle-class history, but with a middle-aged man in a bar (Roger W. Kirby), who appears in one scene and has no proper name and quietly and gently proves that the cherished, obsessively fine-tuned worldviews of the hyper-articulate protagonists are the result of a whole lot of cloistered living.

Metropolitan has no real plot; one day over Christmas break "not very long ago", Princeton student Tom Townsend (Edward Clements) falls in by accident with a gaggle of debutantes and their escorts, a group of friends gathered under the name of the S.F.R.P. or "Sally Fowler Rat Pack": Sally herself (Dylan Hundley), and fellow debs Audrey Rouget (Carolyn Farina), an awkward-looking bookworm, Jane Clark (Allison Parisi), the most sharp-tongued of the group, and Cynthia McLean (Isabel Gillies), the most readily-irritated. Their male companions are Nick Smith (Chris Eigeman), an epic cynic, Charlie Black (Taylor Nichols), who nurtures morbid philosophies about the end times for his class and their lifestyle, and Fred Neff (Bryan Leder), an amiable drunk. Tom finds himself magnetically attached to these people, and spends as much time as he can in the thin window between semesters, though his very presence acts as a destabilising element that hastens the already inevitable fracturing of the S.F.R.P (Clements's red hair, set against the WASPy blonds and brunettes of his new friends, is a particularly elegant visual representation of his essential otherness).

It feels like it ought to be very simple to pigeonhole the film and thus file it away, but this never proves to be the case. It's not quite a lot of different things without being exactly any of them: not quite a Film of Ideas, because while nearly the entire script is full of characters expounding theories about politics and society and morality, we're never given all that much reason to take them seriously; not quite a character study, because we never truly dig into anyone, not even Tom, who occupies the narrative space of the audience surrogate without actually letting us inside his head; not quite a comedy of manners, because it uses neither stock characters nor stock situations, except to specifically overturn the viewer's expectations about them. There are elements of all these things, but the aggregate is an unclassifiable wry, dialogue-driven comedy of observation - about a very specific type of society so archaic that even the people involved are confused by its continued existence, about the lies people tell themselves to make it possible to live, and about the post-adolescent confusion of building a personality out of hundreds of competing stimuli.

The script is terrifyingly literate: explicit references to the social comedies of Jane Austen and oblique shades of The Great Gatsby in Nick and Tom's character names are at the forefront of a gamut of intellectual markers that help to define and shape the way the characters think about themselves, and whenever any of them speak, it's in a uniformly stilted and stylised language that marries beautifully with the heavily old-fashioned society in which the film takes place. It also suggests characters whose first priority is to hear themselves speaking, for whom every conversation is a game; it shows the characters at their most intelligent and witty, while also trapping them inside that same intelligence, for as snappy and articulate as the dialogue is, it invariably gets in the way of actual communication leaving us with a cast full of bright young things who can describe in perfectly-shaped phrases everything other than their feelings.

Stillman's script is so present at every moment that it's easy to overlook how precisely the film has been directed, shot by John Thomas, and edited by future Oscar nominee Christopher Tellefsen in an extremely sharp debut. And, to be fair, this isn't an unmatched masterpiece of visual storytelling, but it does extremely well for a low-budget New York indie, making a virtue out of the inability to use many locations or camera set-ups, so that the film's visual repetition plays into its overall exploration of a tradition-bound, formalistic culture. It's more Ozu than mumblecore, that is to say, and represents a level of awareness of his mise en scène that I think Stillman is rarely credited with. Metropolitan is about talking, yes, but it is also about a place that defines its scenario and characters as much as it creates a specific mood.

But it is, I think, mostly about characters, trying to sort through their own brains ("most of our waking life is taken up thinking to ourselves" claims Charlie, in a typical example of Stillman's ingeniously dry language), while trying to project the appearance of having figured it all out. The importance of appearances to these characters is absolutely omnipresent, from Tom's proud admission that he holds all the right opinions on books he has no desire to read, to a climax in which two of the young men try to force themselves into the role of adventure movie heroes, more because their romantic ideals require it than because there is actually an adventure to be had. Where Metropolitan breaks from other similar treatments of the willful self-delusion of young people lies in Stillman's overwhelmingly generous approach to his cast: he is well aware of how much these people are lying to themselves and the ways that they're setting themselves up to fail - how they fetishise failing, in fact. "That it ceased to exist, I'll grant you, but whether or not it failed cannot be definitively said" is an easy laughline meant to poke holes in Tom's idealistic, cobbled-together faux Socialism, but it also sets up a film-long obsession with the very word "fail", culminating in Charlie's desperate attempt to get the man in the bar to agree that their entire class - U.H.B.s, for "Urban haute bourgeoisie", Charlie's attempt at something more precise than WASPs - is inherently doomed to failure; we understand as the man does, and as the youths do not, that this is Charlie's way of making it okay that he's too lazy and scared to do any of the things that will keep him from failing.

But as I was saying: Stillman knows this is true, and he does not cut the characters slack, but he also does not judge them, and this is critical. It's very hard for filmmakers who know that they are superior to the characters to avoid this temptation, even when they marry criticism with love (as, say, the Coens); Stillman recognises the flaws, and perhaps sees himself in them, and forgives them, just as his Metropolitan fully recognises the archaism and even amorality of the New York debutante scene, but refuses to call for its overthrow - though he also does not romanticise this culture. It's a neat balance. The film is unbelievably aware of class differences in America, and yet it feels apolitical; Stillman is more interested here in journalism than editorialising.

I wonder how much of this is true because of the film itself, and how much is because of the immaculate cast, who all manage to breathe humanity and sympathy into their characters, making it impossible to see them as just caricatures of the upper class - and even more, I wonder how much of it is specifically Eigeman, the not-very-secret weapon of the whole film (the ending deflates rather badly, and after a third viewing, I've concluded that it's not because the whole adventure-thriller framework doesn't fit the film's sensibility, but that the banishment of Nick to his father's house for the last third robs the movie of Eigeman's galvanizing presence). For he plays a character who comes closer to voicing the Moral of the Story than anyone else even dreams of; he is the Jay Gatsby figure, seducing and entrancing Tom and by extension the viewer in Tom's shoes. He is also the sourest and darkest of the characters, particularly as we figure out that his quips are not an attempt to self-aggrandise, as are Charlie's, nor to win points, as are Jane's; he says cynical, acidic things, because he believes them to be true. And yet Eigeman is so effortlessly charismatic that what he says doesn't play as cynicism, but as addictively witty pathos. Who knows if he changed the film Stillman was going to make, or if Stillman and Eigeman had to work hard to get that exact mixture of acid and vitality right. Whatever the case, Nick is the heart and soul and brain of Metropolitan, stylish and smart and completely nihilistic. And goddamn funny; always goddamn funny. None of the rest would matter without a sense of good humor; in fact, would be perilously close to bitter. But between the arch writing and the glib performances, Metropolitan has quite a good sense of humor indeed, one far more fussy and precise and artificial than most movies dare to attempt, and the film is all the more unique and precious for it, two decades and a scattering of imitators later.

There are two terribly important, and tightly related things to know about Metropolitan: it was writer-director-producer Whit Stillman's very first movie, and it was released when Stillman was 38 years old. Aside from providing comfort to any aging wannabe filmmakers out there - you too can become a cause célèbre deep into adulthood! - it provides just exactly the right angle to understand exactly what is going on in a movie that is considerably sneakier and denser than it seems at first blush, not least because on close analysis, Metropolitan is, in fact, saying exactly what it appears to be saying, which means in theory that it's a very surfacey movie. The cunning bit is how on the obvious level, it's saying things in a flippant and ironic and heavily arch way, while with a little bit of digging, is saying those same ways in a far more thoughtful, humanist, and worldly way. It is the same division as that between the main characters - eight college students from upper class Manhattan backgrounds, over-educated and paralysed by too much thinking - and their creator, who despite having something of the same sociopolitical DNA, does not ultimately align himself with any of the youths, not even the one who comes closest to sharing his lapsed-into-middle-class history, but with a middle-aged man in a bar (Roger W. Kirby), who appears in one scene and has no proper name and quietly and gently proves that the cherished, obsessively fine-tuned worldviews of the hyper-articulate protagonists are the result of a whole lot of cloistered living.

Metropolitan has no real plot; one day over Christmas break "not very long ago", Princeton student Tom Townsend (Edward Clements) falls in by accident with a gaggle of debutantes and their escorts, a group of friends gathered under the name of the S.F.R.P. or "Sally Fowler Rat Pack": Sally herself (Dylan Hundley), and fellow debs Audrey Rouget (Carolyn Farina), an awkward-looking bookworm, Jane Clark (Allison Parisi), the most sharp-tongued of the group, and Cynthia McLean (Isabel Gillies), the most readily-irritated. Their male companions are Nick Smith (Chris Eigeman), an epic cynic, Charlie Black (Taylor Nichols), who nurtures morbid philosophies about the end times for his class and their lifestyle, and Fred Neff (Bryan Leder), an amiable drunk. Tom finds himself magnetically attached to these people, and spends as much time as he can in the thin window between semesters, though his very presence acts as a destabilising element that hastens the already inevitable fracturing of the S.F.R.P (Clements's red hair, set against the WASPy blonds and brunettes of his new friends, is a particularly elegant visual representation of his essential otherness).

It feels like it ought to be very simple to pigeonhole the film and thus file it away, but this never proves to be the case. It's not quite a lot of different things without being exactly any of them: not quite a Film of Ideas, because while nearly the entire script is full of characters expounding theories about politics and society and morality, we're never given all that much reason to take them seriously; not quite a character study, because we never truly dig into anyone, not even Tom, who occupies the narrative space of the audience surrogate without actually letting us inside his head; not quite a comedy of manners, because it uses neither stock characters nor stock situations, except to specifically overturn the viewer's expectations about them. There are elements of all these things, but the aggregate is an unclassifiable wry, dialogue-driven comedy of observation - about a very specific type of society so archaic that even the people involved are confused by its continued existence, about the lies people tell themselves to make it possible to live, and about the post-adolescent confusion of building a personality out of hundreds of competing stimuli.

The script is terrifyingly literate: explicit references to the social comedies of Jane Austen and oblique shades of The Great Gatsby in Nick and Tom's character names are at the forefront of a gamut of intellectual markers that help to define and shape the way the characters think about themselves, and whenever any of them speak, it's in a uniformly stilted and stylised language that marries beautifully with the heavily old-fashioned society in which the film takes place. It also suggests characters whose first priority is to hear themselves speaking, for whom every conversation is a game; it shows the characters at their most intelligent and witty, while also trapping them inside that same intelligence, for as snappy and articulate as the dialogue is, it invariably gets in the way of actual communication leaving us with a cast full of bright young things who can describe in perfectly-shaped phrases everything other than their feelings.

Stillman's script is so present at every moment that it's easy to overlook how precisely the film has been directed, shot by John Thomas, and edited by future Oscar nominee Christopher Tellefsen in an extremely sharp debut. And, to be fair, this isn't an unmatched masterpiece of visual storytelling, but it does extremely well for a low-budget New York indie, making a virtue out of the inability to use many locations or camera set-ups, so that the film's visual repetition plays into its overall exploration of a tradition-bound, formalistic culture. It's more Ozu than mumblecore, that is to say, and represents a level of awareness of his mise en scène that I think Stillman is rarely credited with. Metropolitan is about talking, yes, but it is also about a place that defines its scenario and characters as much as it creates a specific mood.

But it is, I think, mostly about characters, trying to sort through their own brains ("most of our waking life is taken up thinking to ourselves" claims Charlie, in a typical example of Stillman's ingeniously dry language), while trying to project the appearance of having figured it all out. The importance of appearances to these characters is absolutely omnipresent, from Tom's proud admission that he holds all the right opinions on books he has no desire to read, to a climax in which two of the young men try to force themselves into the role of adventure movie heroes, more because their romantic ideals require it than because there is actually an adventure to be had. Where Metropolitan breaks from other similar treatments of the willful self-delusion of young people lies in Stillman's overwhelmingly generous approach to his cast: he is well aware of how much these people are lying to themselves and the ways that they're setting themselves up to fail - how they fetishise failing, in fact. "That it ceased to exist, I'll grant you, but whether or not it failed cannot be definitively said" is an easy laughline meant to poke holes in Tom's idealistic, cobbled-together faux Socialism, but it also sets up a film-long obsession with the very word "fail", culminating in Charlie's desperate attempt to get the man in the bar to agree that their entire class - U.H.B.s, for "Urban haute bourgeoisie", Charlie's attempt at something more precise than WASPs - is inherently doomed to failure; we understand as the man does, and as the youths do not, that this is Charlie's way of making it okay that he's too lazy and scared to do any of the things that will keep him from failing.

But as I was saying: Stillman knows this is true, and he does not cut the characters slack, but he also does not judge them, and this is critical. It's very hard for filmmakers who know that they are superior to the characters to avoid this temptation, even when they marry criticism with love (as, say, the Coens); Stillman recognises the flaws, and perhaps sees himself in them, and forgives them, just as his Metropolitan fully recognises the archaism and even amorality of the New York debutante scene, but refuses to call for its overthrow - though he also does not romanticise this culture. It's a neat balance. The film is unbelievably aware of class differences in America, and yet it feels apolitical; Stillman is more interested here in journalism than editorialising.

I wonder how much of this is true because of the film itself, and how much is because of the immaculate cast, who all manage to breathe humanity and sympathy into their characters, making it impossible to see them as just caricatures of the upper class - and even more, I wonder how much of it is specifically Eigeman, the not-very-secret weapon of the whole film (the ending deflates rather badly, and after a third viewing, I've concluded that it's not because the whole adventure-thriller framework doesn't fit the film's sensibility, but that the banishment of Nick to his father's house for the last third robs the movie of Eigeman's galvanizing presence). For he plays a character who comes closer to voicing the Moral of the Story than anyone else even dreams of; he is the Jay Gatsby figure, seducing and entrancing Tom and by extension the viewer in Tom's shoes. He is also the sourest and darkest of the characters, particularly as we figure out that his quips are not an attempt to self-aggrandise, as are Charlie's, nor to win points, as are Jane's; he says cynical, acidic things, because he believes them to be true. And yet Eigeman is so effortlessly charismatic that what he says doesn't play as cynicism, but as addictively witty pathos. Who knows if he changed the film Stillman was going to make, or if Stillman and Eigeman had to work hard to get that exact mixture of acid and vitality right. Whatever the case, Nick is the heart and soul and brain of Metropolitan, stylish and smart and completely nihilistic. And goddamn funny; always goddamn funny. None of the rest would matter without a sense of good humor; in fact, would be perilously close to bitter. But between the arch writing and the glib performances, Metropolitan has quite a good sense of humor indeed, one far more fussy and precise and artificial than most movies dare to attempt, and the film is all the more unique and precious for it, two decades and a scattering of imitators later.