Banish plump Jack, and banish all the world

There are a whole lot of films based on the plays of William Shakespeare - some of them aren't even Romeo and Juliet or Hamlet - and the great majority of them are bad. Alright, "bad" is a strong word: some of them are bad, such as George Cukor's stillborn 1936 Romeo and Juliet that tries to put over a 34-year-old Norma Shearer and 43-year-old Leslie Howard as the dazzled star-crossed lovers, or Kenneth Branagh's criminally misconceived As You Like It from 2006. The vast majority of them are just prestigiously dull mediocrities, with the stand-outs tending be the ones that significantly re-conceive the play down to its very language (Kurosawa's Ran, from King Lear, or Forbidden Planet, from The Tempest), or the ones that are exercises in their own style rather than the actual matter of the play (Julie Taymor's Titus, Baz Luhrmann's Romeo + Juliet), or the ones that are from some other planet entirely (Peter Greenaway's Prospero's Books).

Occasionally, though, you'll stumble across a cinematic adaptation of Shakespeare that is at once faithful to the source material and a genuinely effective piece of cinema; films that can navigate the archaic diction and verse, the staging conventions of Elizabethan drama, and the psychological gulf of 400 years without sacrificing realism or artistry. Laurence Olivier's Henry V is one of these; so is Roman Polanski's Macbeth. Franco Zeffirelli's 1968 Romeo and Juliet has its share of passionate defenders, whose point I see even if I am not quite ready to join them.

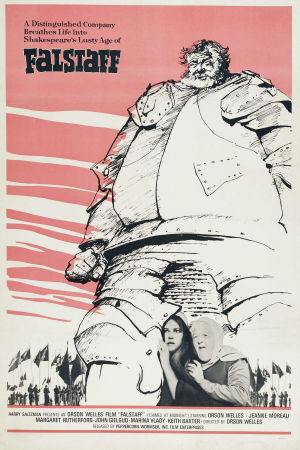

But the best of these "realistic" adaptations, and indeed the best Shakespearean film ever, by my lights, is 1966's Chimes at Midnight, one of the last features completed by the benighted genius Orson Welles during the torturous European exile phase of his career. It is a combination of four plays: primarily a condensation of the matter of Henry IV, Part 1 and Henry IV, Part 2, with a little bit of Richard II to provide context at the beginning and a little bit of Henry V to round off the plot that Shakespeare himself left on a cliffhanger. In this respect, it is the only theatrical version of any of the history plays outside of Richard III or Henry V filmed to date; a significant pity, given that the two Henry IV plays are indisputably better than the former, and at least the equal to the latter, which is their sequel.

In point of fact, though, Chimes at Midnight isn't even that; it's actually all of the scenes featuring the drunken scoundrel of a knight, Sir John Falstaff, with just enough of the historical drama left in to keep the whole thing hanging together. Sort of Henry IV: Only the Best Parts, then, and a miracle of condensation it is too, given that fat old Jack Falstaff is one of the great characters in English literature, and instead of getting some two hours of his blustering and pontificating and robustness in the midst of five hours of warfare and politicking, we just get those two hours, like a hit of pure cocaine. It is, I think, a change that the populist Shakespeare would have welcomed (he wrote a third Falstaff play, the godawful Merry Wives of Windsor, so we know he wasn't above whoring himself to give audiences all the drunken pratfalls they could possibly want to pay for).

This change in material allows Welles to significantly reconfigure the dramatic focus: from the movements of armies and countries to the relationship between a dissolute old man and the only person in the whole world he truly loves, a callow young boy who happens to the Prince of Wales. Their relationship has always been the beating heart of the Henriad, but by cutting out everything extraneous to that main narrative arc, Welles turns a political history into a personal tragicomedy, one that is far more enthralling, entertaining, piercing, and heartbreaking than it would be buried in the midst of all that chatter about events that the average filmgoer in the 1960s wouldn't have been able to place comfortably within 200 years.

It gives Welles the role of a lifetime to play (well, duh, he played it: a famous egotist and prickly auteur, failing to give himself one of the classically great roles? You jest), a compression of the whole gamut of Falstaff into a dense pack with nothing to distract us from the character or the actor, and Welles, it must be said, nails it. Even "nails it" is underselling it. I speak from a position of admitted ignorance, having not seen all of the multiple hundred film and TV versions of Shakespeare, but I can see this much without any hesitation: Welles's Falstaff is the single best filmed performance of any Shakespearean character I can name. And it's not by a very small margin, either. Obviously, that's partially because the very role is such a gift; unlike Hamlet, whose play-defining ambiguity makes it impossible for any single performance to "solve" the part, Falstaff's loud, domineering personality constantly guides the actor down a certain path; there is, more often than not, exactly one way that is obviously right to deliver every single line, and Welles finds them all.

Which isn't to say that it's a lazy or obvious performance, or that the results aren't still incredible: watching the actor's quiet glances, the unguarded moments seen only by the camera where he reveals to us just how much he understands about every other character, is to see film acting at its best, subdued in ways that a theater performance could never be. And even in his bigger, actorly moments, Welles is still a pleasure: his tired recitation of the famous "honor" soliloquy (here wisely restaged as a harangue to an unlistening Prince Hal), his naked yearning to be loved in the moment when he defends his character while pantomiming the prince, his quicksilver streams of rampant bullshit when he's caught in a number of consecutive lies following a foiled robbery: it's hard to imagine a better screen interpretation of any of these moments, among the finest in English drama. The best, I think, is at the very end, following the newly-crowned Henry V's abjuration of the fat villain, when Welles masks his face in an unknowably mysterious half smile: is it shock, or a last conviction that Hal must be joking, or pride that he has raised up such a fine young king, or some combination of all three? It's the most flexible moment in the whole part, and Welles milks it for everything; leaving us open to be completely emotionally walloped by his subsequent line, the devastating-in-context "Master Shallow, I owe you a thousand pound".

On its own, a great performance of Falstaff would be enough to justify; he's a fantastic character, and deserves celluloid immortality. But Chimes at Midnight is an across-the-board masterpiece; Welles ranked it at the top of his own filmography, alongside The Trial, and while it suffers somewhat from the involuntary cheapness that marks all of his European movies - in particular, the dubbing is at times just a step above a Godzilla film, with multiple characters voiced by Welles himself - it's impossible to deny the artistry of one of the medium's great frustrated geniuses. The touch of the man behind Citizen Kane is fully evident in all the shadowboxes made out of the rustic Tudor interiors, with timbers jaggedly slicing across the frame and into the cozy atmosphere like some impossible marriage of German Expressionism and Thomas Kincade. Admittedly, cinematographer Edmond Richard was hardly Gregg Toland, but he was no slouch (his first feature was that same The Trial, as gorgeous as anything to come out of Europe in the 1960s), and there are some remarkable deep-focus shots all through the movie; among the most perfect are a pair that come late in the film, after Prince Hal has become King Henry V, and stands at the far end of a dark, moody throne room separated from the camera by a flock of adoring courtiers; shortly thereafter, this shot is answered by one of Falstaff in the same position in the frame, alone in the brightly lit but horribly empty main room of Mistress Quickly's tavern. Everything we need to know about the emotional stakes for the narrative end game is established in two quick strokes.

The contrast between the castle and the tavern is, in fact, one of the mainstays of the film's visual vocabulary, as Welles and Richard bathe the former in sheets of black, and move through with purposeful, angular tracking shots, while the latter is bright and crowded and the camera swoops in and out madly, moving fluidly but without obvious purpose; they even make use of hand-held cameras long before that had become a thing that people did just because. This isn't subtle: it's contrasting the iciness of the halls of power with the liveliness of Falstaff and his circle, establishing Welles and the film firmly on the side of criticism which holds that fat Jack, for all his obvious immorality and selfishness, is a vital force; he is representative of the drive to be happy and content with oneself, and to enjoy all that life has to offer. He is lust and lustiness, in its greedy sense but also in its broader, more humanist sense. And he is not, himself, a subtle figure, so it fits that he is not expressed in subtle visual language.

I could go on and on about the imagery in the film, and how very characteristic it is of Welles, one of the best visual storytellers America ever produced, but it would reek of fanboyism (one last thing: I adore his framing of the mid-film battle between Henry IV and Percy's armies, particularly a low-angle shot of Falstaff waddling out in full armor as soldiers stream around him; it is, in a very subdued way, a parody of the big historical war epics that had been so much in vogue for the last decade or so when the film was new). Suffice it to say that if I can't quite join Welles in esteeming it at the very top of the director's career, that is only because there are so many riches to choose from in that particular filmography; and I do, for the record, think that it's his best performance. And, for what it's worth, he's got quite a few good actors surrounding him, including a terrifically broad Margaret Rutherford as Mistress Quickly, and John Gielgud "doing a Gielgud" as Henry IV. The surprising stand-out is Keith Baxter, whose career is littered with TV and movies nobody has ever heard of, knocking the role of Hal out of the park; it's arguably the trickiest role in the entire script, easy to play as a snotty teen or to read too much of the future Henry V into it, but Baxter finds a perfect note of filial affection and puffed-up regality, making a perfect foil to Welles at every moment.

As a period film, Chimes at Midnight looks as good as its budget could conceivably allow; it helps that there are surprisingly few locations, though it never feels that way thanks to the acrobatic cinematography. Angelo Francesco Lavagnino's score does a great job of setting the period tone as well, while keeping the mood upbeat - despite its bittersweet finale, Falstaff's tale is essentially comic, and that, too, is part of where the bright visuals and Welles's gigantic performance come in handy, making this, on top of everything else, the funniest Shakespearean movie I know of, although given how few of his comedies even get filmed, and how few of those can figure out how to make his humor work, this is not a tremendously difficult record to set.

It is, all in all, a masterpiece: of Wellesian camerawork and of '60s costume drama, of filmed Shakespeare and of Shakespearean acting. Why it remains so damn hard to see, I can't say; the limbo that has sucked up Welles's Othello apparently got this one as well, though his Macbeth - in my opinion, the least effective of his features - remains a fairly accessible way to see the director's approach to a different kind of Shakespeare altogether. Some day, maybe, Chimes at Midnight will be out in the open for all to enjoy; until then, let those who can scrounge it up be glad that they have the experience of both top-notch Shakespeare and top-notch filmmaking, a rare combination that, when it works, is like nothing else in the whole world.

*Kurosawa Akira's 1985 Ran remains the better film; it is, however, worse Shakespeare.

Occasionally, though, you'll stumble across a cinematic adaptation of Shakespeare that is at once faithful to the source material and a genuinely effective piece of cinema; films that can navigate the archaic diction and verse, the staging conventions of Elizabethan drama, and the psychological gulf of 400 years without sacrificing realism or artistry. Laurence Olivier's Henry V is one of these; so is Roman Polanski's Macbeth. Franco Zeffirelli's 1968 Romeo and Juliet has its share of passionate defenders, whose point I see even if I am not quite ready to join them.

But the best of these "realistic" adaptations, and indeed the best Shakespearean film ever, by my lights, is 1966's Chimes at Midnight, one of the last features completed by the benighted genius Orson Welles during the torturous European exile phase of his career. It is a combination of four plays: primarily a condensation of the matter of Henry IV, Part 1 and Henry IV, Part 2, with a little bit of Richard II to provide context at the beginning and a little bit of Henry V to round off the plot that Shakespeare himself left on a cliffhanger. In this respect, it is the only theatrical version of any of the history plays outside of Richard III or Henry V filmed to date; a significant pity, given that the two Henry IV plays are indisputably better than the former, and at least the equal to the latter, which is their sequel.

In point of fact, though, Chimes at Midnight isn't even that; it's actually all of the scenes featuring the drunken scoundrel of a knight, Sir John Falstaff, with just enough of the historical drama left in to keep the whole thing hanging together. Sort of Henry IV: Only the Best Parts, then, and a miracle of condensation it is too, given that fat old Jack Falstaff is one of the great characters in English literature, and instead of getting some two hours of his blustering and pontificating and robustness in the midst of five hours of warfare and politicking, we just get those two hours, like a hit of pure cocaine. It is, I think, a change that the populist Shakespeare would have welcomed (he wrote a third Falstaff play, the godawful Merry Wives of Windsor, so we know he wasn't above whoring himself to give audiences all the drunken pratfalls they could possibly want to pay for).

This change in material allows Welles to significantly reconfigure the dramatic focus: from the movements of armies and countries to the relationship between a dissolute old man and the only person in the whole world he truly loves, a callow young boy who happens to the Prince of Wales. Their relationship has always been the beating heart of the Henriad, but by cutting out everything extraneous to that main narrative arc, Welles turns a political history into a personal tragicomedy, one that is far more enthralling, entertaining, piercing, and heartbreaking than it would be buried in the midst of all that chatter about events that the average filmgoer in the 1960s wouldn't have been able to place comfortably within 200 years.

It gives Welles the role of a lifetime to play (well, duh, he played it: a famous egotist and prickly auteur, failing to give himself one of the classically great roles? You jest), a compression of the whole gamut of Falstaff into a dense pack with nothing to distract us from the character or the actor, and Welles, it must be said, nails it. Even "nails it" is underselling it. I speak from a position of admitted ignorance, having not seen all of the multiple hundred film and TV versions of Shakespeare, but I can see this much without any hesitation: Welles's Falstaff is the single best filmed performance of any Shakespearean character I can name. And it's not by a very small margin, either. Obviously, that's partially because the very role is such a gift; unlike Hamlet, whose play-defining ambiguity makes it impossible for any single performance to "solve" the part, Falstaff's loud, domineering personality constantly guides the actor down a certain path; there is, more often than not, exactly one way that is obviously right to deliver every single line, and Welles finds them all.

Which isn't to say that it's a lazy or obvious performance, or that the results aren't still incredible: watching the actor's quiet glances, the unguarded moments seen only by the camera where he reveals to us just how much he understands about every other character, is to see film acting at its best, subdued in ways that a theater performance could never be. And even in his bigger, actorly moments, Welles is still a pleasure: his tired recitation of the famous "honor" soliloquy (here wisely restaged as a harangue to an unlistening Prince Hal), his naked yearning to be loved in the moment when he defends his character while pantomiming the prince, his quicksilver streams of rampant bullshit when he's caught in a number of consecutive lies following a foiled robbery: it's hard to imagine a better screen interpretation of any of these moments, among the finest in English drama. The best, I think, is at the very end, following the newly-crowned Henry V's abjuration of the fat villain, when Welles masks his face in an unknowably mysterious half smile: is it shock, or a last conviction that Hal must be joking, or pride that he has raised up such a fine young king, or some combination of all three? It's the most flexible moment in the whole part, and Welles milks it for everything; leaving us open to be completely emotionally walloped by his subsequent line, the devastating-in-context "Master Shallow, I owe you a thousand pound".

On its own, a great performance of Falstaff would be enough to justify; he's a fantastic character, and deserves celluloid immortality. But Chimes at Midnight is an across-the-board masterpiece; Welles ranked it at the top of his own filmography, alongside The Trial, and while it suffers somewhat from the involuntary cheapness that marks all of his European movies - in particular, the dubbing is at times just a step above a Godzilla film, with multiple characters voiced by Welles himself - it's impossible to deny the artistry of one of the medium's great frustrated geniuses. The touch of the man behind Citizen Kane is fully evident in all the shadowboxes made out of the rustic Tudor interiors, with timbers jaggedly slicing across the frame and into the cozy atmosphere like some impossible marriage of German Expressionism and Thomas Kincade. Admittedly, cinematographer Edmond Richard was hardly Gregg Toland, but he was no slouch (his first feature was that same The Trial, as gorgeous as anything to come out of Europe in the 1960s), and there are some remarkable deep-focus shots all through the movie; among the most perfect are a pair that come late in the film, after Prince Hal has become King Henry V, and stands at the far end of a dark, moody throne room separated from the camera by a flock of adoring courtiers; shortly thereafter, this shot is answered by one of Falstaff in the same position in the frame, alone in the brightly lit but horribly empty main room of Mistress Quickly's tavern. Everything we need to know about the emotional stakes for the narrative end game is established in two quick strokes.

The contrast between the castle and the tavern is, in fact, one of the mainstays of the film's visual vocabulary, as Welles and Richard bathe the former in sheets of black, and move through with purposeful, angular tracking shots, while the latter is bright and crowded and the camera swoops in and out madly, moving fluidly but without obvious purpose; they even make use of hand-held cameras long before that had become a thing that people did just because. This isn't subtle: it's contrasting the iciness of the halls of power with the liveliness of Falstaff and his circle, establishing Welles and the film firmly on the side of criticism which holds that fat Jack, for all his obvious immorality and selfishness, is a vital force; he is representative of the drive to be happy and content with oneself, and to enjoy all that life has to offer. He is lust and lustiness, in its greedy sense but also in its broader, more humanist sense. And he is not, himself, a subtle figure, so it fits that he is not expressed in subtle visual language.

I could go on and on about the imagery in the film, and how very characteristic it is of Welles, one of the best visual storytellers America ever produced, but it would reek of fanboyism (one last thing: I adore his framing of the mid-film battle between Henry IV and Percy's armies, particularly a low-angle shot of Falstaff waddling out in full armor as soldiers stream around him; it is, in a very subdued way, a parody of the big historical war epics that had been so much in vogue for the last decade or so when the film was new). Suffice it to say that if I can't quite join Welles in esteeming it at the very top of the director's career, that is only because there are so many riches to choose from in that particular filmography; and I do, for the record, think that it's his best performance. And, for what it's worth, he's got quite a few good actors surrounding him, including a terrifically broad Margaret Rutherford as Mistress Quickly, and John Gielgud "doing a Gielgud" as Henry IV. The surprising stand-out is Keith Baxter, whose career is littered with TV and movies nobody has ever heard of, knocking the role of Hal out of the park; it's arguably the trickiest role in the entire script, easy to play as a snotty teen or to read too much of the future Henry V into it, but Baxter finds a perfect note of filial affection and puffed-up regality, making a perfect foil to Welles at every moment.

As a period film, Chimes at Midnight looks as good as its budget could conceivably allow; it helps that there are surprisingly few locations, though it never feels that way thanks to the acrobatic cinematography. Angelo Francesco Lavagnino's score does a great job of setting the period tone as well, while keeping the mood upbeat - despite its bittersweet finale, Falstaff's tale is essentially comic, and that, too, is part of where the bright visuals and Welles's gigantic performance come in handy, making this, on top of everything else, the funniest Shakespearean movie I know of, although given how few of his comedies even get filmed, and how few of those can figure out how to make his humor work, this is not a tremendously difficult record to set.

It is, all in all, a masterpiece: of Wellesian camerawork and of '60s costume drama, of filmed Shakespeare and of Shakespearean acting. Why it remains so damn hard to see, I can't say; the limbo that has sucked up Welles's Othello apparently got this one as well, though his Macbeth - in my opinion, the least effective of his features - remains a fairly accessible way to see the director's approach to a different kind of Shakespeare altogether. Some day, maybe, Chimes at Midnight will be out in the open for all to enjoy; until then, let those who can scrounge it up be glad that they have the experience of both top-notch Shakespeare and top-notch filmmaking, a rare combination that, when it works, is like nothing else in the whole world.

*Kurosawa Akira's 1985 Ran remains the better film; it is, however, worse Shakespeare.