Then fall, Caesar

In 2008, Beau Willimon, a young writer and veteran of the Howard Dean '04 presidential campaign, saw the debut of a new play, Farragut North. This was more or less a process story about the incredible soul-sucking misery of life in a campaign, in which a Wunderkind media mind hitched his star to a transformative Democratic primary candidate, and how the brash, arrogant kid was destroyed utterly as a result of being a little too cocksure. Though it came from an unmistakably liberal place, it was not primarily about policy so much as the string of horrible choices even the most decent people have to make to survive in the land of electoral politics.

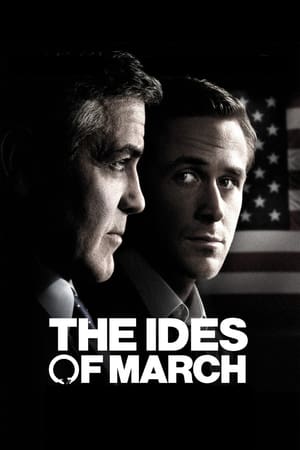

Three inordinately long years later, with the Hope and Change that were thick in the air in the days that Farragut North made its bow now lurched over a men's room toilet voiding themselves of the last raggedy vestiges of promise, George Clooney - who also comes from an unmistakably liberal place - has directed an adaptation of that play which he co-wrote with his regular partner Grant Heslov (Willimon gets a credit, but I suspect it's for the glut of lines taken directly from the play & nothing else); the title has been leadingly changed to The Ides of March (mainstream audience can't stand subtle titles, you see), and the focus changed considerably, away from the boots on the ground reality of campaign life to a grander personal tragedy; and the relative apoliticism of the play (the progressive hopeful around whom everyone's hopes and dreams revolve is never seen and barely matters) has been replaced by a stern message about the mirage of truly progressive politicians, and how the people who promise the most about changing the way politics are done are all the more heartbreaking when they inevitable fail to be the paladins they seem. It is verily the version of this story for our present moment in history, just as Farragut North was perfectly situated in 2008; and at the same time, it is not quite as intelligent, by dint of being mainstreamified: the play is fascinated by the lingo and mentality of campaigns to a far greater degree, while the movie is just another "fall of a pie-eyed idealist" story, and one not entirely benefited by its director, whose instincts are far too safe for any of his movies to leave very much of an impression beyond being nice and grown-up and a little too ready for the Oscar spotlight to do anything actually clever.

Ryan Gosling plays our main character, Stephen Myers, the 30-year-old genius serving as Junior Campaign Manger for Democratic hopeful Mike Morris (Clooney), the current Pennsylvania governor. It's Ohio, about a week before the primary, and Morris barely leads Senator Ted Pullman in delegates for the nomination; it is fair to say that the entire race depends on the outcome of this state. Stephen and his boss, Paul Zara (Phil Seymour Hoffman) are doing their best to work crazy magic and secure the governor's nomination, when one day the younger man receives a call from Tom Duffy (Paul Giamatti), Pullman's campaign manager. Though he angrily rebuffs Duffy's offer to take him on board, Stephen's decision to take this meeting proves disastrously bad, and it puts a serious strain on his ability to do his work. But it's not the only thing falling apart on him; his new casual sexual relationship with campaign intern Molly Stearns (Evan Rachel Wood), daughter of the sitting DNC chairman, takes a turn for the ghastly when he learns that the young woman not only slept with Morris, but is pregnant with his child.

This is at heart the story of Stephen's fall from innocence: on the one hand because he learns that his idol Morris is capable of being just as venal and stupid as any man (he adroitly notes at one point that fucking an intern is the only unforgivable sin in politics), and on the other because he finds that he is capable of the most savagely cynical behavior in the name of maintaining personal power and winning - not winning because he wants his ideology in control, but for the mere fact of it. In this respect it is a fine movie, not least because of Gosling's steady performance, nicely delineating each moment of Stephen's break from idealism, though it is not very impressive within the actor's demonstrated range of abilities (he's far better in Drive, where he's playing a deliberately unfathomable cipher). The script is literate and knowing, and the cast is game - Clooney even manages to clamp down on his inherent charisma when the character needs it. It's not an earth-shaker, but it's eminently solid prestige picture craftsmanship; unexciting though Clooney's directing may be, he sure knows how to hire the hell out of talented sonsabitches like Alexandre Desplat and Stephen Mirrione.

It is also, though, a story of disappointment and disgust: a frustration with the unbending corruption of the electoral system made by a man who can't stand the fact that everything is going to hell in a fast car and nobody seems to want to change things. It's a bit of a "pox on both your houses" scream of despair: the Republicans are written off as beyond hope (the writers could not possibly have imagined the absurd state that would exist in October, 2011 when they tossed off a few lines about the GOP's difficulty in finding a decent candidate), and the Democrats are exposed as being just as venal and worthless, only they're not as good at it.

And this theme, at least, I'm not inclined to fault, except that Clooney the filmmaker is simply too non-confrontational to actually tell that story, even though that's exactly the part of the script that embellishes the most on the play. Thus, exactly where the film needs to draw blood, it holds back; where it needs to wallow with nihilistic relish in the shitstorm that the country is turning into, it demurs, and except for a single line delivered by Morris suggesting higher tax rates for the rich, The Ides of March is almost perversely unwilling to actually be about the world. In the end, the niceness endemic to Clooney's directorial work (though not, really, to the things he has merely produced or starred in) wins out, and though an altogether nice film about the rotten state of contemporary politics might be good for an award nomination or two, it's not really designed to say anything terribly significant or meaningful about its nominal subject.

7/10

Three inordinately long years later, with the Hope and Change that were thick in the air in the days that Farragut North made its bow now lurched over a men's room toilet voiding themselves of the last raggedy vestiges of promise, George Clooney - who also comes from an unmistakably liberal place - has directed an adaptation of that play which he co-wrote with his regular partner Grant Heslov (Willimon gets a credit, but I suspect it's for the glut of lines taken directly from the play & nothing else); the title has been leadingly changed to The Ides of March (mainstream audience can't stand subtle titles, you see), and the focus changed considerably, away from the boots on the ground reality of campaign life to a grander personal tragedy; and the relative apoliticism of the play (the progressive hopeful around whom everyone's hopes and dreams revolve is never seen and barely matters) has been replaced by a stern message about the mirage of truly progressive politicians, and how the people who promise the most about changing the way politics are done are all the more heartbreaking when they inevitable fail to be the paladins they seem. It is verily the version of this story for our present moment in history, just as Farragut North was perfectly situated in 2008; and at the same time, it is not quite as intelligent, by dint of being mainstreamified: the play is fascinated by the lingo and mentality of campaigns to a far greater degree, while the movie is just another "fall of a pie-eyed idealist" story, and one not entirely benefited by its director, whose instincts are far too safe for any of his movies to leave very much of an impression beyond being nice and grown-up and a little too ready for the Oscar spotlight to do anything actually clever.

Ryan Gosling plays our main character, Stephen Myers, the 30-year-old genius serving as Junior Campaign Manger for Democratic hopeful Mike Morris (Clooney), the current Pennsylvania governor. It's Ohio, about a week before the primary, and Morris barely leads Senator Ted Pullman in delegates for the nomination; it is fair to say that the entire race depends on the outcome of this state. Stephen and his boss, Paul Zara (Phil Seymour Hoffman) are doing their best to work crazy magic and secure the governor's nomination, when one day the younger man receives a call from Tom Duffy (Paul Giamatti), Pullman's campaign manager. Though he angrily rebuffs Duffy's offer to take him on board, Stephen's decision to take this meeting proves disastrously bad, and it puts a serious strain on his ability to do his work. But it's not the only thing falling apart on him; his new casual sexual relationship with campaign intern Molly Stearns (Evan Rachel Wood), daughter of the sitting DNC chairman, takes a turn for the ghastly when he learns that the young woman not only slept with Morris, but is pregnant with his child.

This is at heart the story of Stephen's fall from innocence: on the one hand because he learns that his idol Morris is capable of being just as venal and stupid as any man (he adroitly notes at one point that fucking an intern is the only unforgivable sin in politics), and on the other because he finds that he is capable of the most savagely cynical behavior in the name of maintaining personal power and winning - not winning because he wants his ideology in control, but for the mere fact of it. In this respect it is a fine movie, not least because of Gosling's steady performance, nicely delineating each moment of Stephen's break from idealism, though it is not very impressive within the actor's demonstrated range of abilities (he's far better in Drive, where he's playing a deliberately unfathomable cipher). The script is literate and knowing, and the cast is game - Clooney even manages to clamp down on his inherent charisma when the character needs it. It's not an earth-shaker, but it's eminently solid prestige picture craftsmanship; unexciting though Clooney's directing may be, he sure knows how to hire the hell out of talented sonsabitches like Alexandre Desplat and Stephen Mirrione.

It is also, though, a story of disappointment and disgust: a frustration with the unbending corruption of the electoral system made by a man who can't stand the fact that everything is going to hell in a fast car and nobody seems to want to change things. It's a bit of a "pox on both your houses" scream of despair: the Republicans are written off as beyond hope (the writers could not possibly have imagined the absurd state that would exist in October, 2011 when they tossed off a few lines about the GOP's difficulty in finding a decent candidate), and the Democrats are exposed as being just as venal and worthless, only they're not as good at it.

And this theme, at least, I'm not inclined to fault, except that Clooney the filmmaker is simply too non-confrontational to actually tell that story, even though that's exactly the part of the script that embellishes the most on the play. Thus, exactly where the film needs to draw blood, it holds back; where it needs to wallow with nihilistic relish in the shitstorm that the country is turning into, it demurs, and except for a single line delivered by Morris suggesting higher tax rates for the rich, The Ides of March is almost perversely unwilling to actually be about the world. In the end, the niceness endemic to Clooney's directorial work (though not, really, to the things he has merely produced or starred in) wins out, and though an altogether nice film about the rotten state of contemporary politics might be good for an award nomination or two, it's not really designed to say anything terribly significant or meaningful about its nominal subject.

7/10