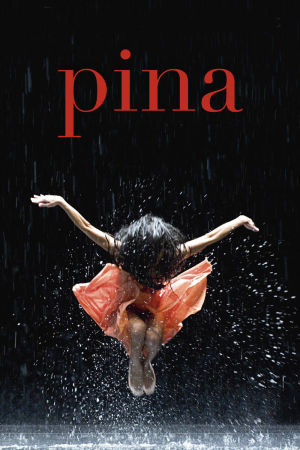

The 47th Chicago International Film Festival

Screens at CIFF: 10/18

World premiere: 13 February, 2011, Berlin Film Festival

Pina Bausch was a woman who was, until very recently indeed, completely unknown to me; and it's maybe the most concise way to explain just how good Wim Wender's film about her work is, if I simply say that Pina - for that is the film's unpushy title - has left me convinced that she was one of the most uncommonly gifted minds in the world of dance (if not of the performing arts more generally) of her generation.

"Was", I say, because sadly Bausch died just shy of her 69th birthday in 2009, at which point she and Wenders, a personal friend, had only just begun work on the movie. At that point, it turned into a tribute to her life and the uncanny effect she seems to have had on a great many artistic collaborators, and especially a chance to record some of her choreography in exhiliratingly crisp 3-D for future generations to be able to know her work.

Now I say that I did not know Pina Bausch as even a name until this movie; and if it is chief among Pina's triumphs that it made me a ravening fanboy in the space of 100 minutes, chief among its flaws is that I left the movie without actually knowing a damn thing about her. Not in the airy, biopic-ish manner of "Bausch was driven to dance because of this or that trauma in her youth", but in the very practical and real world sense that Wenders tells us nothing about her influence, her theories, her guiding principals, her role in the history of the art form, or even the city in which her studio was located* - a bizarre science-fiction German city where the elevated trains are suspended from above, but that's neither here nor there.

Of course, this perceived lack has more to do with what I want out of Pina than what Wenders wants, which is to allow the work to speak for itself, and that is hardly an artistic crime. Particularly when the work is so expressive as Bausch's dances, of which we see a good number in whole or in part, including what I gather are her two signature pieces, a version of The Rite of Spring that covers the stage in geometric patterns of soil which very literally grounds the dancers in the grubby reality of the piece and forced to make exaggerated, heavy movements, and Café Müller, a rather terrifying and desperate fantasy piece in which a number of indistinct human figures are trapped in an interior space full of chairs and tables, crashing into objects and each other in their dislocated stumbling. These are left mostly as Bausch designed them; other pieces are staged in various natural or industrial places: a construction site, a train car, in the middle of a brook.

That the dances are brilliant, the film takes as given; but just as brilliant is Wenders's presentation of those dances to the camera. Setting aside the location shooting, there is very little in these sequences that considerably editorialises Bausch's original work: a couple of POV shots in Rite of Spring, and the substitution through editing of three entire ensembles, one young, one middle-aged, and one elderly, in a dance called Kontakthof, are the only purely cinematic gestures in the movie. Which is a million miles away from calling the film "uncinematic": it is, rather, desperately and richly cinematic, using the camera to direct our attention, change our perspective, and significantly alter our sense of the space and the shape of the dancer's bodies; and it's here that the 3-D really becomes important. One of the things that Bausch's choreography seems particularly concerned with is the relative position of the body and its limbs and other bodies surrounding it (I know nothing of the scholarship surrounding her work, and maybe what I just said is the most asinine, illiterate piece of dance criticism in the world), and our attention as film viewers is directed with laserlike precision to these details through the 3-D: we are made to consider the separation of body parts, and the orientation of them: I don't know that I have seen another movie that insisted with quite this much force on the human body as a three-dimensional object. It is, at any rate, the most comprehensive and intelligent use of the technology that I have yet seen - and it's kind of wonderful that between this and Cave of Forgotten Dreams, it's taken the two superstars of the New German Cinema making documentaries to show off the heights that 3-D could reach.

As a documentary, I've already mentioned that the film is a bit uninformative, and I'll double down by saying that the various interviews with Bausch's dancers, which mostly boil down to the lovely but empty sentiment that Pina Bausch always encouraged artists to follow their own insight and creativity are nothing but deadwood in the film as it stands (they would have fit, I think, much better in a film more about Bausch and less about her work). So maybe, let's not force Pina to be a documentary; just allow it to be a performance piece. By which standard it is a truly exceptional achievement: at its best, this film includes some of the very finest dance cinematography I have ever seen, and is thus a triumph in two different artistic mediums.

9/10

World premiere: 13 February, 2011, Berlin Film Festival

Pina Bausch was a woman who was, until very recently indeed, completely unknown to me; and it's maybe the most concise way to explain just how good Wim Wender's film about her work is, if I simply say that Pina - for that is the film's unpushy title - has left me convinced that she was one of the most uncommonly gifted minds in the world of dance (if not of the performing arts more generally) of her generation.

"Was", I say, because sadly Bausch died just shy of her 69th birthday in 2009, at which point she and Wenders, a personal friend, had only just begun work on the movie. At that point, it turned into a tribute to her life and the uncanny effect she seems to have had on a great many artistic collaborators, and especially a chance to record some of her choreography in exhiliratingly crisp 3-D for future generations to be able to know her work.

Now I say that I did not know Pina Bausch as even a name until this movie; and if it is chief among Pina's triumphs that it made me a ravening fanboy in the space of 100 minutes, chief among its flaws is that I left the movie without actually knowing a damn thing about her. Not in the airy, biopic-ish manner of "Bausch was driven to dance because of this or that trauma in her youth", but in the very practical and real world sense that Wenders tells us nothing about her influence, her theories, her guiding principals, her role in the history of the art form, or even the city in which her studio was located* - a bizarre science-fiction German city where the elevated trains are suspended from above, but that's neither here nor there.

Of course, this perceived lack has more to do with what I want out of Pina than what Wenders wants, which is to allow the work to speak for itself, and that is hardly an artistic crime. Particularly when the work is so expressive as Bausch's dances, of which we see a good number in whole or in part, including what I gather are her two signature pieces, a version of The Rite of Spring that covers the stage in geometric patterns of soil which very literally grounds the dancers in the grubby reality of the piece and forced to make exaggerated, heavy movements, and Café Müller, a rather terrifying and desperate fantasy piece in which a number of indistinct human figures are trapped in an interior space full of chairs and tables, crashing into objects and each other in their dislocated stumbling. These are left mostly as Bausch designed them; other pieces are staged in various natural or industrial places: a construction site, a train car, in the middle of a brook.

That the dances are brilliant, the film takes as given; but just as brilliant is Wenders's presentation of those dances to the camera. Setting aside the location shooting, there is very little in these sequences that considerably editorialises Bausch's original work: a couple of POV shots in Rite of Spring, and the substitution through editing of three entire ensembles, one young, one middle-aged, and one elderly, in a dance called Kontakthof, are the only purely cinematic gestures in the movie. Which is a million miles away from calling the film "uncinematic": it is, rather, desperately and richly cinematic, using the camera to direct our attention, change our perspective, and significantly alter our sense of the space and the shape of the dancer's bodies; and it's here that the 3-D really becomes important. One of the things that Bausch's choreography seems particularly concerned with is the relative position of the body and its limbs and other bodies surrounding it (I know nothing of the scholarship surrounding her work, and maybe what I just said is the most asinine, illiterate piece of dance criticism in the world), and our attention as film viewers is directed with laserlike precision to these details through the 3-D: we are made to consider the separation of body parts, and the orientation of them: I don't know that I have seen another movie that insisted with quite this much force on the human body as a three-dimensional object. It is, at any rate, the most comprehensive and intelligent use of the technology that I have yet seen - and it's kind of wonderful that between this and Cave of Forgotten Dreams, it's taken the two superstars of the New German Cinema making documentaries to show off the heights that 3-D could reach.

As a documentary, I've already mentioned that the film is a bit uninformative, and I'll double down by saying that the various interviews with Bausch's dancers, which mostly boil down to the lovely but empty sentiment that Pina Bausch always encouraged artists to follow their own insight and creativity are nothing but deadwood in the film as it stands (they would have fit, I think, much better in a film more about Bausch and less about her work). So maybe, let's not force Pina to be a documentary; just allow it to be a performance piece. By which standard it is a truly exceptional achievement: at its best, this film includes some of the very finest dance cinematography I have ever seen, and is thus a triumph in two different artistic mediums.

9/10

Categories: ciff, documentaries, musicals, the third dimension