The films of Sergio Leone

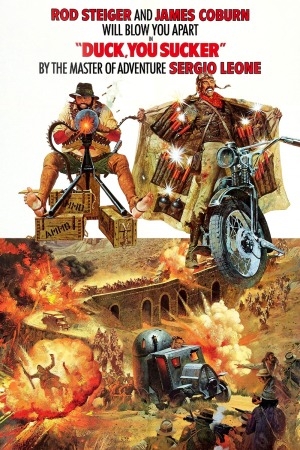

Beginning with Once Upon a Time in the West, in 1968, it becomes difficult to separate the facts in the case of Sergio Leone from the complex layers of myth that he eagerly gathered around himself once it became clear that he was an Important Director. That means that one cannot trust all the details of the various anecdotes surrounding the creation of the 1971 Western Giù la testa, a film that has been known in English-speaking parts by the titles A Fistful of Dynamite and Duck, You Sucker (the latter is the accurate translation), depending less upon the content of the cut than upon what year the release was happening. The story we are told, however, is that Leone was feeling a bit Westerned-out after Once Upon a Time in the West and the Dollars Trilogy - four movies that internationally reinvigorated the genre when it seemed about ready to die, and which the director cranked out like epic, violent sausages over a dainty four-year span - and he was looking to do absolutely anything else for a time. Thus, although he planned to produce Duck, You Sucker, a film for which he'd already written the screenplay (alongside regular co-writers Sergio Donati and Luciano Vincenzoni), he was hoping to collaborate with some other director on actually getting the thing made. Here's where the myths start to crowd in, and they tend to be myths that aggrandise Leone's prominence and importance and all-round awesomeness, which is why I'm content to reject them out of hand, but the short version is that he was obliged to direct the film himself, making his fifth Western in a seven-year span. And this much at least I will happily believe: he was sick and tired of Westerns.

The evidence for that contention is all over the movie, you see, for Duck, You Sucker feels an awful lot like a Western made by somebody who has run out of things to do with the form. Not because it is tired or lazy or routine: the exact opposite. Duck, You Sucker is incontestably one of the damn weirdest Westerns that I have ever seen, though I have not seen a great many Italian Westerns from the early '70s, and none at all in its particular subgenre, the "Zapata Westerns" that were set during the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s. Perhaps they were all a similar blend of Western, war movie, political tract, and buddy comedy. I would tend to doubt it, except if there's one thing I have learned in my life as a cinephile, it's that you never assume with Italian genre films.

As I was saying, though: weird movie, in plot and execution, and I expect that this was Leone's way of insuring himself against boredom, genre fatigue, and the artistically deadly sin of repeating himself. As a result, Duck, You Sucker is if nothing else a sign of continued evolution - in what direction, I cannot readily say. Certainly, it feels "smaller" than Once Upon a Time in the West and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, and though it is not without its well-conceived setpieces, they are not so self-consciously operatic; thus does the film seem, perhaps unfairly, to be less important and aesthetically succulent. But not more of the same - never more of the same. Even if Duck, You Sucker represents a step in a direction best not headed (and please, allow me to stress the importance of that "if"), it is still a bold step, and a broad one.

The movie opens with a lengthy prologue, though we do not recognise it as being such until afterward, in which we're introduced to Juan Miranda (Rod Steiger), leader of a gang of bandits that seems to consist primarily of his sons. We meet him pissing on a rock in the middle of nowhere, a crude & earthy moment that gets to the heart of the film's ultimate theme - but let me postpone that. Having relieved himself, Juan hops on a ludicrously opulent stagecoach and receives all manner of class-based abuse from the wealthy folks on board, taking it all meekly, before surprising them (and us, theoretically) by holding up the coach and stripping down all the men and forcing them to jump naked into a cart, before tossing the single woman among the passengers (Maria Monti) on top of the rest of them. She is, incidentally, the only woman with a significant speaking role in the movie, in case you were uncertain about that theme of "Sergio Leone doesn't like women" that I've taken to developing.

This hijacking and the fallout takes about 25 minutes, after which our grubby movie about a Marxist bandit is interrupted by the arrival of John Mallory, an explosions expert from the IRA hiding out in America, played with loopy élan and an inconsistent accent by James Coburn. Juan immediately sees in this ex-pat the key to executing the robbery of the Banco Nacional de Mesa Verde - in what is incontestably the strangest moment in a film of perverse peculiarities, Juan sees John with a glowing banner displaying the bank's name superimposed above his head - and manages to bully the Irishman into joining his gang; but John gets the last laugh, when the bank turns out to have been converted into a prison for revolutionaries - which he had known about all along - and for his action in freeing so many political prisoners, the politically agnostic Juan is hailed as a hero of the Revolution. After this, Duck, You Sucker turns into a fascinatingly disjointed hybrid of Western and combat film. The plot almost ceases to matter, as the two men begin to form a bond of mutual respect and friendship while crossing paths with various revolutionaries and government soldiers.

It's hard to go much deeper into the plot than that without also confronting the film's political message - and for the first time in Leone's career, he's making a no-doubt-about-it message movie, after being sincerely but unsystematically anti-violence and anti-war in his preceding four, extravagantly violent and war-torn films. It's not, in the event, a tremendously comfortable fit for the director.

All throughout the film, Juan voices a strong objection to the Revolution as a matter of fools, one side of intellectuals pitting the poor masses against the armies of another side of intellectuals. He gets not one but two big speeches about how it's all bullshit - his word, in a passionate screed about how the Revolution chews men up and spits them out. And it appears at one remove that Leone agrees with him: for in his movie, the violence of the Revolution is not noble and tragically necessary, but filthy and nasty and horrible: the greatest moment in the film, to me, is undoubtedly a long tracking shot that goes up and down and back and forth across a cave floor strewn with an uncountable number of dead bodies, the enthusiastic peasants who went forth and followed the revolutionary call, and after that moment any thought of romanticising their deaths is quite impossible.

On the other hand, Leone stacks the deck against the Mexican government and upper classes so robustly that it's equally impossible to assume that he isn't ideologically in sync with the Revolution: while some of the individual revolutionaries are traitors, backstabbers, or just merciless bastards, the people they're fighting are flat-out monsters, with the film's chief antagonist, Colonel Reza (Antoine Saint-John) sports a rich German accent, and a well-developed sense of cruelty that would, in a movie set 30 years later, mark him as a cartoonishly evil SS officer. Not to mention Leone's apparently unironic quotation of Mao's statement that "The Revolution is not a dinner party..." as the opening cards of his movie.

I will admit, with no small amount of shame, that I first assumed that the tension between these two points was a sign of the film's internal incoherence. Upon reflection, though I suspect that the film is espousing a kind of nihilism about the whole thing: clowns to the left, jokers to the right, and stuck in the middle are two men, one a fervent idealist and one a battle-scarred pragmatist. That's what the film actually ends up being about, mostly: Juan and John learning from each other and understanding one another in the face of senselessness and confusion. So only a "kind of" nihilism; it can also be seen as Leone's sunniest Western, in that it suggests, for the first time, that the bonds of friendship are actually valuable and real, an idea that would have been blithely dismissed by the Man with No Name or Harmonica. Of course, the bonds of friendship are also powerless in the face of death and destruction; for "sunniest" is relative and Leone is a particularly brutal filmmaker.

Anyway, all of this theory and whathaveyou is good and all, but the downside is that the film gets a bit too serious and talkative, and though at 157 minutes in its longest version, it is not tremendously long by Leone standards, it is the only one of his Westerns that I think suffers from padding. Or perhaps, due to its other various flaws, things seem to be padding that wouldn't have in his earlier films (certainly, whatever merits The Good, the Bad and the Ugly claims, narrative efficiency is not one of them). Not least of these flaws is how present the message is: another is the cast. Steiger and Coburn plays characters intended for Eli Wallach and Jason Robards, and while Coburn doesn't do the film any harm - his characterisation of John avoids all the tight-lipped seriousness that the role would seem to encourage, suggesting instead that his terrible experiences with the rebellion in Ireland, scene in flashbacks, have turned him completely, cheerfully insane - Steiger tries too hard and ends up being inflexible and far too obviously "acting", and it gets much worse when you start to think about how Wallach would have done in the same part. Wallach would have had the same amount of crazed fun with the part that Coburn has with his; together they would have made Duck, You Sucker almost like a violent farce about revolution. Instead, the central relationship upon which the whole film hinges is never quite convincing.

Still, the film was made by a talented visual artist, and if at times it feels like a regression to the style of For a Few Dollars More, it's ultimately more about the interaction of characters than the confluence of characters with one another and the landscape surrounding them, which makes the simpler aesthetic a fine fit: only in one or two action sequences does the absence of the grand excess of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and Once Upon a Time in the West hurt the film very much, simply because it doesn't have the same sweeping moments - there is nothing here even remotely analogous to the three-way standoff at the end of TGTBTU, and the big emotional payoff of the movie is done almost entirely in a medium shot-reverse shot that fits the moment exactly right. Cinematographer Giuseppe Ruzzolini, working with Leone for the first time, doesn't capture the Andalusian desert with the same sense of apocalyptic desperation that had come by this point to typify the Leone style, but he doesn't really need to: the film is simpler than that, for good and for ill.

The one collaborator, as always, who pushes the film into truly ambitious territory is Ennio Morricone, whose score is almost certainly the strangest part of an off-kilter movie: his theme for John is an assortment of barbarous Irishisms and electronic squawks; while he scores the bank robbery with music that sounds like the underscore to a Mickey Mouse cartoon, spliced with quotes from Mozart's Eine kleine Nachtmusik, and turns an action sequence into a comic setpiece - which sounds like he's ruining it, but it actually ends up being one of the most memorable bits of the movie. The score is not as beautiful as his more famous work, but it's perhaps the single most important element that elevates Duck, You Sucker into a legitimately significant Western, instead of a curiosity: for the music always keeps the film dancing on a knife's edge even when everything else is fumbling around underneath Leone's somewhat overworked scenario. The film may lack the intuitive energy of the director's best work, but it sounds the part.

The evidence for that contention is all over the movie, you see, for Duck, You Sucker feels an awful lot like a Western made by somebody who has run out of things to do with the form. Not because it is tired or lazy or routine: the exact opposite. Duck, You Sucker is incontestably one of the damn weirdest Westerns that I have ever seen, though I have not seen a great many Italian Westerns from the early '70s, and none at all in its particular subgenre, the "Zapata Westerns" that were set during the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s. Perhaps they were all a similar blend of Western, war movie, political tract, and buddy comedy. I would tend to doubt it, except if there's one thing I have learned in my life as a cinephile, it's that you never assume with Italian genre films.

As I was saying, though: weird movie, in plot and execution, and I expect that this was Leone's way of insuring himself against boredom, genre fatigue, and the artistically deadly sin of repeating himself. As a result, Duck, You Sucker is if nothing else a sign of continued evolution - in what direction, I cannot readily say. Certainly, it feels "smaller" than Once Upon a Time in the West and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, and though it is not without its well-conceived setpieces, they are not so self-consciously operatic; thus does the film seem, perhaps unfairly, to be less important and aesthetically succulent. But not more of the same - never more of the same. Even if Duck, You Sucker represents a step in a direction best not headed (and please, allow me to stress the importance of that "if"), it is still a bold step, and a broad one.

The movie opens with a lengthy prologue, though we do not recognise it as being such until afterward, in which we're introduced to Juan Miranda (Rod Steiger), leader of a gang of bandits that seems to consist primarily of his sons. We meet him pissing on a rock in the middle of nowhere, a crude & earthy moment that gets to the heart of the film's ultimate theme - but let me postpone that. Having relieved himself, Juan hops on a ludicrously opulent stagecoach and receives all manner of class-based abuse from the wealthy folks on board, taking it all meekly, before surprising them (and us, theoretically) by holding up the coach and stripping down all the men and forcing them to jump naked into a cart, before tossing the single woman among the passengers (Maria Monti) on top of the rest of them. She is, incidentally, the only woman with a significant speaking role in the movie, in case you were uncertain about that theme of "Sergio Leone doesn't like women" that I've taken to developing.

This hijacking and the fallout takes about 25 minutes, after which our grubby movie about a Marxist bandit is interrupted by the arrival of John Mallory, an explosions expert from the IRA hiding out in America, played with loopy élan and an inconsistent accent by James Coburn. Juan immediately sees in this ex-pat the key to executing the robbery of the Banco Nacional de Mesa Verde - in what is incontestably the strangest moment in a film of perverse peculiarities, Juan sees John with a glowing banner displaying the bank's name superimposed above his head - and manages to bully the Irishman into joining his gang; but John gets the last laugh, when the bank turns out to have been converted into a prison for revolutionaries - which he had known about all along - and for his action in freeing so many political prisoners, the politically agnostic Juan is hailed as a hero of the Revolution. After this, Duck, You Sucker turns into a fascinatingly disjointed hybrid of Western and combat film. The plot almost ceases to matter, as the two men begin to form a bond of mutual respect and friendship while crossing paths with various revolutionaries and government soldiers.

It's hard to go much deeper into the plot than that without also confronting the film's political message - and for the first time in Leone's career, he's making a no-doubt-about-it message movie, after being sincerely but unsystematically anti-violence and anti-war in his preceding four, extravagantly violent and war-torn films. It's not, in the event, a tremendously comfortable fit for the director.

All throughout the film, Juan voices a strong objection to the Revolution as a matter of fools, one side of intellectuals pitting the poor masses against the armies of another side of intellectuals. He gets not one but two big speeches about how it's all bullshit - his word, in a passionate screed about how the Revolution chews men up and spits them out. And it appears at one remove that Leone agrees with him: for in his movie, the violence of the Revolution is not noble and tragically necessary, but filthy and nasty and horrible: the greatest moment in the film, to me, is undoubtedly a long tracking shot that goes up and down and back and forth across a cave floor strewn with an uncountable number of dead bodies, the enthusiastic peasants who went forth and followed the revolutionary call, and after that moment any thought of romanticising their deaths is quite impossible.

On the other hand, Leone stacks the deck against the Mexican government and upper classes so robustly that it's equally impossible to assume that he isn't ideologically in sync with the Revolution: while some of the individual revolutionaries are traitors, backstabbers, or just merciless bastards, the people they're fighting are flat-out monsters, with the film's chief antagonist, Colonel Reza (Antoine Saint-John) sports a rich German accent, and a well-developed sense of cruelty that would, in a movie set 30 years later, mark him as a cartoonishly evil SS officer. Not to mention Leone's apparently unironic quotation of Mao's statement that "The Revolution is not a dinner party..." as the opening cards of his movie.

I will admit, with no small amount of shame, that I first assumed that the tension between these two points was a sign of the film's internal incoherence. Upon reflection, though I suspect that the film is espousing a kind of nihilism about the whole thing: clowns to the left, jokers to the right, and stuck in the middle are two men, one a fervent idealist and one a battle-scarred pragmatist. That's what the film actually ends up being about, mostly: Juan and John learning from each other and understanding one another in the face of senselessness and confusion. So only a "kind of" nihilism; it can also be seen as Leone's sunniest Western, in that it suggests, for the first time, that the bonds of friendship are actually valuable and real, an idea that would have been blithely dismissed by the Man with No Name or Harmonica. Of course, the bonds of friendship are also powerless in the face of death and destruction; for "sunniest" is relative and Leone is a particularly brutal filmmaker.

Anyway, all of this theory and whathaveyou is good and all, but the downside is that the film gets a bit too serious and talkative, and though at 157 minutes in its longest version, it is not tremendously long by Leone standards, it is the only one of his Westerns that I think suffers from padding. Or perhaps, due to its other various flaws, things seem to be padding that wouldn't have in his earlier films (certainly, whatever merits The Good, the Bad and the Ugly claims, narrative efficiency is not one of them). Not least of these flaws is how present the message is: another is the cast. Steiger and Coburn plays characters intended for Eli Wallach and Jason Robards, and while Coburn doesn't do the film any harm - his characterisation of John avoids all the tight-lipped seriousness that the role would seem to encourage, suggesting instead that his terrible experiences with the rebellion in Ireland, scene in flashbacks, have turned him completely, cheerfully insane - Steiger tries too hard and ends up being inflexible and far too obviously "acting", and it gets much worse when you start to think about how Wallach would have done in the same part. Wallach would have had the same amount of crazed fun with the part that Coburn has with his; together they would have made Duck, You Sucker almost like a violent farce about revolution. Instead, the central relationship upon which the whole film hinges is never quite convincing.

Still, the film was made by a talented visual artist, and if at times it feels like a regression to the style of For a Few Dollars More, it's ultimately more about the interaction of characters than the confluence of characters with one another and the landscape surrounding them, which makes the simpler aesthetic a fine fit: only in one or two action sequences does the absence of the grand excess of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and Once Upon a Time in the West hurt the film very much, simply because it doesn't have the same sweeping moments - there is nothing here even remotely analogous to the three-way standoff at the end of TGTBTU, and the big emotional payoff of the movie is done almost entirely in a medium shot-reverse shot that fits the moment exactly right. Cinematographer Giuseppe Ruzzolini, working with Leone for the first time, doesn't capture the Andalusian desert with the same sense of apocalyptic desperation that had come by this point to typify the Leone style, but he doesn't really need to: the film is simpler than that, for good and for ill.

The one collaborator, as always, who pushes the film into truly ambitious territory is Ennio Morricone, whose score is almost certainly the strangest part of an off-kilter movie: his theme for John is an assortment of barbarous Irishisms and electronic squawks; while he scores the bank robbery with music that sounds like the underscore to a Mickey Mouse cartoon, spliced with quotes from Mozart's Eine kleine Nachtmusik, and turns an action sequence into a comic setpiece - which sounds like he's ruining it, but it actually ends up being one of the most memorable bits of the movie. The score is not as beautiful as his more famous work, but it's perhaps the single most important element that elevates Duck, You Sucker into a legitimately significant Western, instead of a curiosity: for the music always keeps the film dancing on a knife's edge even when everything else is fumbling around underneath Leone's somewhat overworked scenario. The film may lack the intuitive energy of the director's best work, but it sounds the part.