John Hughes Retrospective: What we found out is that each one of us is a brain, and an athlete, and a basket case, and a princess, and a criminal.

The right thing is to first begin with the horrible admission, and it is that I was 29 years and 9 months and 7 days old the very first time that I saw John Hughes's iconic teensploitation picture The Breakfast Club, which happens to have been the day before writing this review. I bring this up because being a breath away from the start of one's fourth decade on this Earth is a somewhat unfortunate time to make the acquaintance of a film that, even by the standards of the hyper-nostalgic world of '80s movies, seems to have entranced the vast majority of its hefty fanbase because those fans had the good fortune to watch the movie for the first time when they were about the same age as the characters depicted onscreen, i.e. 15-18 years old, and have never quite shaken the feeling of how it spoke to them when they were at that tender, vulnerable age.

Not that it's a bad movie. In fact, I will own to being very, very surprised that it's not a bad movie. It is, however, a movie that has far more problems than its reputation would suggest, the kind of flaws that can be very readily glossed over in a fit of fond remembrance. At any rate, I didn't find it at all as true as John Hughes's previous work, Sixteen Candles, though his sophomore effort as a director is undeniably more self-assured and mature in its craftsmanship, and lacks the outrageouness of his debut's most objectionable elements (viz. Long Duk Dong, who will haunt my nightmares until I die or The Hangover, Part III comes out, though I expect those two events will occur at about the same time).

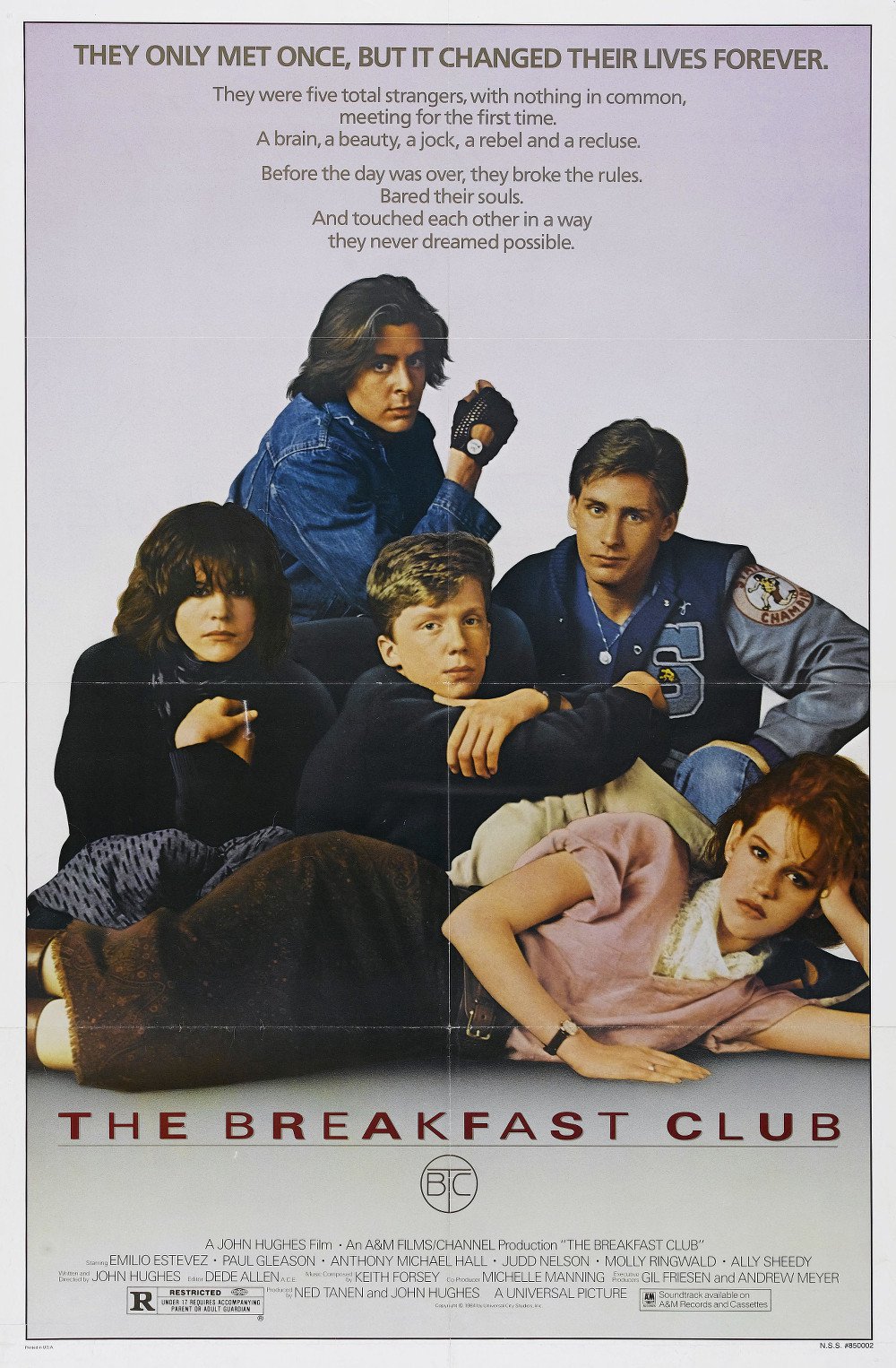

In case you have somehow managed to remain ignorant of the film's content, possibly by eschewing any and all contact with English-language cinema in the last 25 years, it's a bit like this: on 24 March, 1984, at Shermer High School in Shermer, Illinois (and thus does Hughes's fictional version of Northbrook, IL receive its permanent name in honor of that city's former name of Shermerville), five students are held for an all-Saturday detention: Brian Johnson (Anthony Michael Hall), Andrew Clark (Emilio Estevez), Allison Reynolds (Ally Sheedy), Claire Standish (Molly Ringwald), and John Bender (Judd Nelson), who are introduced in Brian's opening monologue as five archetypes of high school: the Brain, the Athlete, the Basket Case,* the Princess, and the Criminal. Over the course of the day's nine hours and the movie's 98 minutes, those five individuals move from mutual incomprehension and loathing to a chain of soul-baring sessions by which they learn that they're too complex as people to be reduced to stereotypical labels.

Structurally and conceptually, this is a fairly brilliant movie, or at least a colossally nervy one. Even if only because of its defiantly uncinematic devotion to the Aristotelian unities, with some 80% of the film taking place in a single room, though thanks to some singularly tight editing (by the great Dede Allen, so no surprise there) it never even once registers that we're watching, in essence, a stage play. Formally, at least, it's the editing where the film works the best, and where Hughes's shooting style is most evolved - late in the film, there is a big climactic sequence in which all of the characters are revealing their darkest truths, and finally breaking through the "roles" that they're expected to play to find that they can, in fact, connect with people from outside of their pre-approved social units. This lengthy scene consists almost solely of close-ups of individuals, and for the great bulk of it that fact nagged me like an itchy T-shirt tag: "This is their big bonding moment!" I wanted to cry, "use a fucking two-shot to demonstrate that visually! You're just reinforcing the paradigm that they don't know how to exist in each other's space!" And then the sequence ends with an oh-so-casual cut to the five of them in mystified silence, just a nice solid whack of a cut that made my heart stop for a few seconds. It's a coup de montage that you would not expect from what is, after all, a genre picture, and though this is the most striking moment of all, it's not even slightly the only dazzling piece of editing. And it's not the kind of editing you need to be a film junkie to appreciate; to notice it, maybe, but that kind of shocking violation of an editing rhythm is something you feel intuitively, like music.

The other thing that's so bloody brave is that Hughes effectively courts cliché by making his five characters embody the blandest stereotypes possible, so that he can shatter those stereotypes from within. It's a fantastic trick, if you can do it right. Here, then, is where the film's legions of fans and I part ways, because I don't really thing Hughes did it right. There are two problems, basically: one is that the stereotypes work so damn well, and we spend so much time with all of them, that the transition at the end isn't entirely believable. The other is that the film is really just trading one stereotype for another, but I'll return to that.

For about 70 minutes of the movie, we are subjected to one moment after another of the kids behaving exactly as they're "meant" to, and it's decently amusing - the film can't decide whether it's a comedy or a drama with comic incidents, but it doesn't really matter, it works either way. Over the course of the movie, they all realise that it's possible to have fun with people they're not "supposed to" hang out with, and it's lovely and charming. But the more that Serious Talks sneak in, the more contrived it all feels, until the big final scene - the one that's so snazzily edited - when we're meant to see that these people are all so concerned with their socially-mandated shells that nobody has ever noticed all the humanity and hurt inside. They're not stereotypes, dammit, they're people!

Except... except their hurt and humanity is itself stereotypical. The Princess is torn in half by her parents' sham marriage of convenience. The Criminal is just mean because his father abuses him. The Brain is so despondent over getting a bad grade that he wants to kill himself. Those are all valid, real-life issues, but they are also the exact issues that you'd give these characters if you wanted to reinforce all of the lazy clichés about your stock character. And given how much exertion the film puts into telling us in its best Message Movie tones that these figures are better than cliché, the only possible conclusion I can come to is that writer-director Hughes was spectacularly unimaginative, and we know from other evidence that this cannot be true.

I did not, mind, include Andrew and Allison, for two very different reasons: Andrew is the one genuinely rounded, unexpected character in the bunch - less so now than he'd have been in 1985, perhaps, since he has been copied so many times, but the whole sensitive athlete with a poet's soul thing is just discordant enough to seem fresh (by my reckoning, Estevez gives the best performance, and that can't be a coincidence). Allison, meanwhile, makes no goddamn sense - she's a Manic Pixie Dream Girl, basically, communicating through yolps and strange gestures until she starts talking and tries to impress on us how freespirited she is. Unsurprisingly, she and Brian are the designated Author Avatars - the smart writer, and the playful artist, those two most beloved vehicles of writers and creative types (but let me not give Hughes too much shit about it: writers identify with what they know, which is writing - Billy Wilder and Sunset Blvd. this is not, and was not supposed to be), but if Allison makes any sense at all as a character, I don't see it - my fault, perhaps, for not being born in 1970 and taking part in this world firsthand. She also gets saddled with an unforgivable ending in which she has to give up her personality and conform to the "right" idea of looks in order to get a boy. It was grating when that happened in Grease: here, in a film with a pronounced anti-conformity message, it reeks of hypocrisy.

Anyway, there's an out to all of this, and it goes like this. The big, super-famous ending speech, which subtly recycles the opening speech with a more pronounced "fuck you, adults!" bent, comes right out and says in giant screaming letters, "We are all God's perfect snowflakes who cannot be contained in one little box. We know this because we're all able to relate to one another despite having different backgrounds." The kicker, though, is when they go around repeating their five roles, and claiming that all five of them contain elements of all five clichés.

Maybe it's just my curmudgeonly soul talking, but what this says to me is: "we're all special because we're all so similar to one another", and if that's not irony, I don't know what is. Part of me likes to think that The Breakfast Club is just a huge piss-take: demonstrating in a remarkably subtle way that American teenagers manage to turn even anti-conformity into a role they're playing; certainly the fact that most of the characters announce that they know deep down that this wonderful catharsis isn't going to last once school picks up on Monday suggests that Hughes didn't really believe the contrived bullshit of the last five minutes, in which people pair off just because they damn well can.

Then again, these are teenagers we're talking about: not, as a class, the most logical or settled subset of humanity. And maybe that's what the film is demonstrating, that adolescents are inherently erratic and questing people who haven't figured out who they are yet and use social roles as props to get them intact into adulthood. That's at least a more charitable take on it, but it leaves us with a Breakfast Club that does a damn poor job of fulfilling its mission statement as a celebration of the inner lives of the young.

Maybe just maybe, the lesson from all of this is that people shouldn't write generational statements for folks 20 years younger than they are.

Ordinarily, I don't like to end by trying to justify myself, but I feel I have to here. If I have been harsh on the movie, it's largely because it came down on such a lofty reputation of being a true and wonderful and meaningful depiction of teenage life, like it was some kind of masterpiece, and I didn't get that at all. One overreacts, maybe, in such circumstances; but there are enough people talking about what works in the film, and not so many taking it to task. The hell of it is, I actually liked the movie: in the beginning, when it's all John "Social Observer" Hughes documenting the ways that different cliques and economic classes interact in the absence of supervision, the thing is every bit the equal of Sixteen Candles, if not better. It does more with the unspoken tension of the North Shore's division into old money and lower-middle class strivers than any of Hughes's other films. And besides Estevez, Ringwald and Hall are great, developing their John Hughes Stock Company personae in satisfying ways (I am told that many people love Judd Nelson in this. That is their right). It's only the last 20 minutes that come along and completely fuck everything up, and turn a satisfying comedy-drama into a miserable attempt at saying Something Important that doesn't, not one iota. In my opinion, of course, and the odds say that your opinion is different. But then, does not The Breakfast Club itself teach us that differences of opinion are necessary and good?

Not that it's a bad movie. In fact, I will own to being very, very surprised that it's not a bad movie. It is, however, a movie that has far more problems than its reputation would suggest, the kind of flaws that can be very readily glossed over in a fit of fond remembrance. At any rate, I didn't find it at all as true as John Hughes's previous work, Sixteen Candles, though his sophomore effort as a director is undeniably more self-assured and mature in its craftsmanship, and lacks the outrageouness of his debut's most objectionable elements (viz. Long Duk Dong, who will haunt my nightmares until I die or The Hangover, Part III comes out, though I expect those two events will occur at about the same time).

In case you have somehow managed to remain ignorant of the film's content, possibly by eschewing any and all contact with English-language cinema in the last 25 years, it's a bit like this: on 24 March, 1984, at Shermer High School in Shermer, Illinois (and thus does Hughes's fictional version of Northbrook, IL receive its permanent name in honor of that city's former name of Shermerville), five students are held for an all-Saturday detention: Brian Johnson (Anthony Michael Hall), Andrew Clark (Emilio Estevez), Allison Reynolds (Ally Sheedy), Claire Standish (Molly Ringwald), and John Bender (Judd Nelson), who are introduced in Brian's opening monologue as five archetypes of high school: the Brain, the Athlete, the Basket Case,* the Princess, and the Criminal. Over the course of the day's nine hours and the movie's 98 minutes, those five individuals move from mutual incomprehension and loathing to a chain of soul-baring sessions by which they learn that they're too complex as people to be reduced to stereotypical labels.

Structurally and conceptually, this is a fairly brilliant movie, or at least a colossally nervy one. Even if only because of its defiantly uncinematic devotion to the Aristotelian unities, with some 80% of the film taking place in a single room, though thanks to some singularly tight editing (by the great Dede Allen, so no surprise there) it never even once registers that we're watching, in essence, a stage play. Formally, at least, it's the editing where the film works the best, and where Hughes's shooting style is most evolved - late in the film, there is a big climactic sequence in which all of the characters are revealing their darkest truths, and finally breaking through the "roles" that they're expected to play to find that they can, in fact, connect with people from outside of their pre-approved social units. This lengthy scene consists almost solely of close-ups of individuals, and for the great bulk of it that fact nagged me like an itchy T-shirt tag: "This is their big bonding moment!" I wanted to cry, "use a fucking two-shot to demonstrate that visually! You're just reinforcing the paradigm that they don't know how to exist in each other's space!" And then the sequence ends with an oh-so-casual cut to the five of them in mystified silence, just a nice solid whack of a cut that made my heart stop for a few seconds. It's a coup de montage that you would not expect from what is, after all, a genre picture, and though this is the most striking moment of all, it's not even slightly the only dazzling piece of editing. And it's not the kind of editing you need to be a film junkie to appreciate; to notice it, maybe, but that kind of shocking violation of an editing rhythm is something you feel intuitively, like music.

The other thing that's so bloody brave is that Hughes effectively courts cliché by making his five characters embody the blandest stereotypes possible, so that he can shatter those stereotypes from within. It's a fantastic trick, if you can do it right. Here, then, is where the film's legions of fans and I part ways, because I don't really thing Hughes did it right. There are two problems, basically: one is that the stereotypes work so damn well, and we spend so much time with all of them, that the transition at the end isn't entirely believable. The other is that the film is really just trading one stereotype for another, but I'll return to that.

For about 70 minutes of the movie, we are subjected to one moment after another of the kids behaving exactly as they're "meant" to, and it's decently amusing - the film can't decide whether it's a comedy or a drama with comic incidents, but it doesn't really matter, it works either way. Over the course of the movie, they all realise that it's possible to have fun with people they're not "supposed to" hang out with, and it's lovely and charming. But the more that Serious Talks sneak in, the more contrived it all feels, until the big final scene - the one that's so snazzily edited - when we're meant to see that these people are all so concerned with their socially-mandated shells that nobody has ever noticed all the humanity and hurt inside. They're not stereotypes, dammit, they're people!

Except... except their hurt and humanity is itself stereotypical. The Princess is torn in half by her parents' sham marriage of convenience. The Criminal is just mean because his father abuses him. The Brain is so despondent over getting a bad grade that he wants to kill himself. Those are all valid, real-life issues, but they are also the exact issues that you'd give these characters if you wanted to reinforce all of the lazy clichés about your stock character. And given how much exertion the film puts into telling us in its best Message Movie tones that these figures are better than cliché, the only possible conclusion I can come to is that writer-director Hughes was spectacularly unimaginative, and we know from other evidence that this cannot be true.

I did not, mind, include Andrew and Allison, for two very different reasons: Andrew is the one genuinely rounded, unexpected character in the bunch - less so now than he'd have been in 1985, perhaps, since he has been copied so many times, but the whole sensitive athlete with a poet's soul thing is just discordant enough to seem fresh (by my reckoning, Estevez gives the best performance, and that can't be a coincidence). Allison, meanwhile, makes no goddamn sense - she's a Manic Pixie Dream Girl, basically, communicating through yolps and strange gestures until she starts talking and tries to impress on us how freespirited she is. Unsurprisingly, she and Brian are the designated Author Avatars - the smart writer, and the playful artist, those two most beloved vehicles of writers and creative types (but let me not give Hughes too much shit about it: writers identify with what they know, which is writing - Billy Wilder and Sunset Blvd. this is not, and was not supposed to be), but if Allison makes any sense at all as a character, I don't see it - my fault, perhaps, for not being born in 1970 and taking part in this world firsthand. She also gets saddled with an unforgivable ending in which she has to give up her personality and conform to the "right" idea of looks in order to get a boy. It was grating when that happened in Grease: here, in a film with a pronounced anti-conformity message, it reeks of hypocrisy.

Anyway, there's an out to all of this, and it goes like this. The big, super-famous ending speech, which subtly recycles the opening speech with a more pronounced "fuck you, adults!" bent, comes right out and says in giant screaming letters, "We are all God's perfect snowflakes who cannot be contained in one little box. We know this because we're all able to relate to one another despite having different backgrounds." The kicker, though, is when they go around repeating their five roles, and claiming that all five of them contain elements of all five clichés.

Maybe it's just my curmudgeonly soul talking, but what this says to me is: "we're all special because we're all so similar to one another", and if that's not irony, I don't know what is. Part of me likes to think that The Breakfast Club is just a huge piss-take: demonstrating in a remarkably subtle way that American teenagers manage to turn even anti-conformity into a role they're playing; certainly the fact that most of the characters announce that they know deep down that this wonderful catharsis isn't going to last once school picks up on Monday suggests that Hughes didn't really believe the contrived bullshit of the last five minutes, in which people pair off just because they damn well can.

Then again, these are teenagers we're talking about: not, as a class, the most logical or settled subset of humanity. And maybe that's what the film is demonstrating, that adolescents are inherently erratic and questing people who haven't figured out who they are yet and use social roles as props to get them intact into adulthood. That's at least a more charitable take on it, but it leaves us with a Breakfast Club that does a damn poor job of fulfilling its mission statement as a celebration of the inner lives of the young.

Maybe just maybe, the lesson from all of this is that people shouldn't write generational statements for folks 20 years younger than they are.

Ordinarily, I don't like to end by trying to justify myself, but I feel I have to here. If I have been harsh on the movie, it's largely because it came down on such a lofty reputation of being a true and wonderful and meaningful depiction of teenage life, like it was some kind of masterpiece, and I didn't get that at all. One overreacts, maybe, in such circumstances; but there are enough people talking about what works in the film, and not so many taking it to task. The hell of it is, I actually liked the movie: in the beginning, when it's all John "Social Observer" Hughes documenting the ways that different cliques and economic classes interact in the absence of supervision, the thing is every bit the equal of Sixteen Candles, if not better. It does more with the unspoken tension of the North Shore's division into old money and lower-middle class strivers than any of Hughes's other films. And besides Estevez, Ringwald and Hall are great, developing their John Hughes Stock Company personae in satisfying ways (I am told that many people love Judd Nelson in this. That is their right). It's only the last 20 minutes that come along and completely fuck everything up, and turn a satisfying comedy-drama into a miserable attempt at saying Something Important that doesn't, not one iota. In my opinion, of course, and the odds say that your opinion is different. But then, does not The Breakfast Club itself teach us that differences of opinion are necessary and good?

Categories: comedies, john hughes, message pictures, teen movies, very serious movies