John Hughes (Screenwriting) Retrospective: Sex and death

To later generations, John Hughes is all but indistinguishable from the genre of teen angst comedies that he helped to create in the 1980s, but it was not ever thus. Hughes began his career as a joke writer for stand-up comedians, and an advertising copywriter, and eventually a staffer on the National Lampoon magazine during its mid-'70s heyday. Among the many charms of National Lampoon cannot be counted its bittersweet but lighthearted and innocuous look at the travails of adolescence: it was, in its time, regarded as something wanton and vulgar and altogether sassy. It was this tone that informed Animal House, the gleefully crass 1978 sex comedy that represented National Lampoon's first stab at movie production, and which remains by a considerable margin the brand's best-known offering in any medium (I should admit up top that while I enjoyed the movie well enough when I first saw it ages ago, there hasn't been a minute since when I've been inclined to see it again).

After Animal House made a shocking sum of money, it was a dead certainty that the National Lampoon imprint would be used on future movies, especially future movies in the same vein of gross-out absurdity that made Animal House such a watershed film in the late '70s, and which became in the blink of an eye a major trend in cinema, with crude sex comedies blanketing the moviegoing landscape like beer-soaked fratboys passed out on the lawn. For the first of these, the powers-that-be turned to Hughes, 32 years old and the author of some very well-received pieces for the magazine, to write the screenplay; having already proved himself by writing several episodes of the Animal House television spin-off Delta House, Hughes must have at least seemed to be sufficiently battle-tested that he would be a solid choice for the job, though the fact that Delta House only lasted one ill-received season might have been seen as a poor augury.

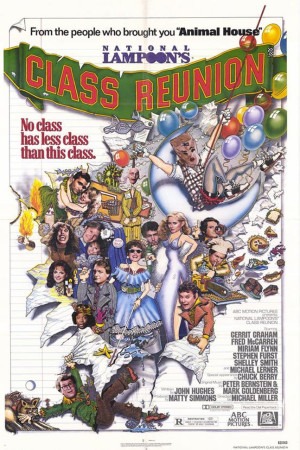

At any rate, Hughes turned in the script for National Lampoon's Class Reunion, which saw the light of day in 1982 under the direction of Michael Miller, whose career ended up encompassing a goodly number of made-for-TV Danielle Steel adaptations. The film bombed and threatened to destroy the National Lampoon label right from the start (though chance would have it that another Hughes script would save the brand, the following year), and though like any failure the movie has its devoted cult, it doesn't take a lot of staring to understand that the reason Class Reunion didn't make any money is that it's no damn good. Hughes himself even conceded, later in life, that he was ashamed of it.

The shape of the thing is that the 1972 graduating class of Lizzie Borden High is gathering for their class reunion, with all the attendant "God I remember you" "God I hated you" "God I still hate you" reminiscing and nostalgia that goes along with it. Except in this case, the reunion is spoiled by the class geek Walter Baylor (Blackie Dammett), who was the victim of an especially humiliating sexual prank in front of the whole senior class just before graduation, and who has spent the intervening decade in a mental institution, nursing his plot for the moment when he'll take his murderous revenge.

If there was one lowbrow subgenre more inescapable in the early '80s than the teen sex farce, it was the slasher film, and the one thing about Class Reunion that truly brought a smile to my face was its combination of those two beasts into one giant parodistic mess (I have to assume that it's not the only such hybrid, but I cannot name another), although the chief feeling one gets from the result is that either John Hughes or Michael Miller - or, let's be generous, both of them - didn't have a very good handle on what went into either a sex farce or a slasher movie. Or more likely, didn't care enough to do a good job of mocking them, for as history shows, the key to a good parody is that the artist making the parody has real, honest affection for the target. Certainly, Hughes's later career suggests very strongly that, while he might have started his career with National Lampoon, he had no particular use for their style of enthusiastic tastelessness.

In fact, the film ends up resembling neither Animal House with grown-ups, nor any sort of travesty of the slasher form, but Airplane! done without a portion of the wacky creativity. That's the film which the dialogue most resembles, anyway, if you ignore the fact that Airplane! has funny lines and Class Reunion doesn't, and the film's structure is basically the same - that is to say there is no structure, just a free-flowing array of gags pinned to the spine of "a killer is in the building, and everyone is freaking out". That these gags have no particular relevance to anything and do not in any way grow out of the situation or the characters is apparently immaterial. How else to explain the character of Delores (Zane Buzby, who gives what is probably the closest to a good performance the film has to offer), who sold her soul to the Devil in order to regain the use of her legs after graduation and is now possessed by a demon? Other than offering the filmmakers the chance to reference the 9-year-old The Exorcist, there's not a blessed bloody thing that this arbitrary violation of whatever baseline reality otherwise governs the film needs to take place (see also: the completely arbitrary and barely-used vampire transfer student, played by Jim Staahl). And yet, there is a fire-breathing demon woman in a movie that nominally wants to be the next Animal House, right alongside the tight-ass snob (Gerrit Graham) and the horny fat guy (Stephen Furst) and the boring hero (Fred McCarren) and the "comically" accident-prone blind girl (Mews Small).*

There is virtually nothing good about the film, but it is not bad in a compelling or instructive way: it's just a crappy, unfunny R-rated comedy that pulls all of its punches. If not for the branding and the future career of the screenwriter, there would be not the slightest point of interest attached to the project. Even then, it's only of minor importance: if one can connect Class Reunion to Hughes's later career at all, it might be through the school setting, or the pointed observation of social roles in high school culture, but it is frankly insulting to the man to suggest that Class Reunion looks ahead to The Breakfast Club in any meaningful way. For our present purposes, let it suffice that the thing exists and gave Hughes his first feature credit, and be glad that he was very quickly able to shake off the stink of it and move on to better and more personally rewarding things.

After Animal House made a shocking sum of money, it was a dead certainty that the National Lampoon imprint would be used on future movies, especially future movies in the same vein of gross-out absurdity that made Animal House such a watershed film in the late '70s, and which became in the blink of an eye a major trend in cinema, with crude sex comedies blanketing the moviegoing landscape like beer-soaked fratboys passed out on the lawn. For the first of these, the powers-that-be turned to Hughes, 32 years old and the author of some very well-received pieces for the magazine, to write the screenplay; having already proved himself by writing several episodes of the Animal House television spin-off Delta House, Hughes must have at least seemed to be sufficiently battle-tested that he would be a solid choice for the job, though the fact that Delta House only lasted one ill-received season might have been seen as a poor augury.

At any rate, Hughes turned in the script for National Lampoon's Class Reunion, which saw the light of day in 1982 under the direction of Michael Miller, whose career ended up encompassing a goodly number of made-for-TV Danielle Steel adaptations. The film bombed and threatened to destroy the National Lampoon label right from the start (though chance would have it that another Hughes script would save the brand, the following year), and though like any failure the movie has its devoted cult, it doesn't take a lot of staring to understand that the reason Class Reunion didn't make any money is that it's no damn good. Hughes himself even conceded, later in life, that he was ashamed of it.

The shape of the thing is that the 1972 graduating class of Lizzie Borden High is gathering for their class reunion, with all the attendant "God I remember you" "God I hated you" "God I still hate you" reminiscing and nostalgia that goes along with it. Except in this case, the reunion is spoiled by the class geek Walter Baylor (Blackie Dammett), who was the victim of an especially humiliating sexual prank in front of the whole senior class just before graduation, and who has spent the intervening decade in a mental institution, nursing his plot for the moment when he'll take his murderous revenge.

If there was one lowbrow subgenre more inescapable in the early '80s than the teen sex farce, it was the slasher film, and the one thing about Class Reunion that truly brought a smile to my face was its combination of those two beasts into one giant parodistic mess (I have to assume that it's not the only such hybrid, but I cannot name another), although the chief feeling one gets from the result is that either John Hughes or Michael Miller - or, let's be generous, both of them - didn't have a very good handle on what went into either a sex farce or a slasher movie. Or more likely, didn't care enough to do a good job of mocking them, for as history shows, the key to a good parody is that the artist making the parody has real, honest affection for the target. Certainly, Hughes's later career suggests very strongly that, while he might have started his career with National Lampoon, he had no particular use for their style of enthusiastic tastelessness.

In fact, the film ends up resembling neither Animal House with grown-ups, nor any sort of travesty of the slasher form, but Airplane! done without a portion of the wacky creativity. That's the film which the dialogue most resembles, anyway, if you ignore the fact that Airplane! has funny lines and Class Reunion doesn't, and the film's structure is basically the same - that is to say there is no structure, just a free-flowing array of gags pinned to the spine of "a killer is in the building, and everyone is freaking out". That these gags have no particular relevance to anything and do not in any way grow out of the situation or the characters is apparently immaterial. How else to explain the character of Delores (Zane Buzby, who gives what is probably the closest to a good performance the film has to offer), who sold her soul to the Devil in order to regain the use of her legs after graduation and is now possessed by a demon? Other than offering the filmmakers the chance to reference the 9-year-old The Exorcist, there's not a blessed bloody thing that this arbitrary violation of whatever baseline reality otherwise governs the film needs to take place (see also: the completely arbitrary and barely-used vampire transfer student, played by Jim Staahl). And yet, there is a fire-breathing demon woman in a movie that nominally wants to be the next Animal House, right alongside the tight-ass snob (Gerrit Graham) and the horny fat guy (Stephen Furst) and the boring hero (Fred McCarren) and the "comically" accident-prone blind girl (Mews Small).*

There is virtually nothing good about the film, but it is not bad in a compelling or instructive way: it's just a crappy, unfunny R-rated comedy that pulls all of its punches. If not for the branding and the future career of the screenwriter, there would be not the slightest point of interest attached to the project. Even then, it's only of minor importance: if one can connect Class Reunion to Hughes's later career at all, it might be through the school setting, or the pointed observation of social roles in high school culture, but it is frankly insulting to the man to suggest that Class Reunion looks ahead to The Breakfast Club in any meaningful way. For our present purposes, let it suffice that the thing exists and gave Hughes his first feature credit, and be glad that he was very quickly able to shake off the stink of it and move on to better and more personally rewarding things.