Blockbuster History: Spy parodies

Every Sunday this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: let us set aside the other issues surrounding Pixar's Cars 2, and think of it as being the latest in the long and storied history of comic films about spies, a genre far older than you think it is: both spy movies and parodies of spy movies can be found all the way back in the silent era. But for now, let's set our sights a little more recent, with one of the earliest examples of what we mostly think about when we hear the phrase "spy parody": a cheeky piss-take of the James Bond films that came out when those films were still the hot new thing.

The 1960s were, all in all, a really damn weird time for pop culture. The Space Age, the Jet Set, the nascent Sexual Revolution, set the stage for pretty much the all-time coolest era of all time between, roughly, 1960 and 1967: when popular culture featured the Rat Pack, the British Invasion, Jean-Luc Godard's early funny ones, Fellini's period of greatest popularity, et al ad nauseum. It could only have been in this bubbling pool of arch-coolness and expanding sexual openness that world cinema could have been graced by the screen debut of British spy James Bond, a hyper-competent, hyper-masculine hero who was first introduced in the early '50s in print, though it seems kind of hard if not impossible to imagine his cinematic persona coming into existence much earlier than 1962, when director Terence Young's Dr. No turned Ian Fleming's brutally efficient, womanising spy into a brutally efficient, womanising spy and hardcore epicure (the film Bond's noted love of fine alcohol, clothes, and the luxury lifestyle being noted an extension of Young's own preoccupations).

The Bond pictures were a huge success, and like any huge success spawned immediate spoofs and imitations. The Italian film industry, for example, was essentially running of the proceeds of Bond knock-offs for several years, while English-language producers on both sides of the Atlantic were quick to come up with glamorous spy narratives of their own, from the intensely sober (as 1965's The Spy Who Came in from the Cold) to the less-sober - such as the hallucinatory 1967 Casino Royale, which is indeed the opposite of sober by just about every definition of the word.

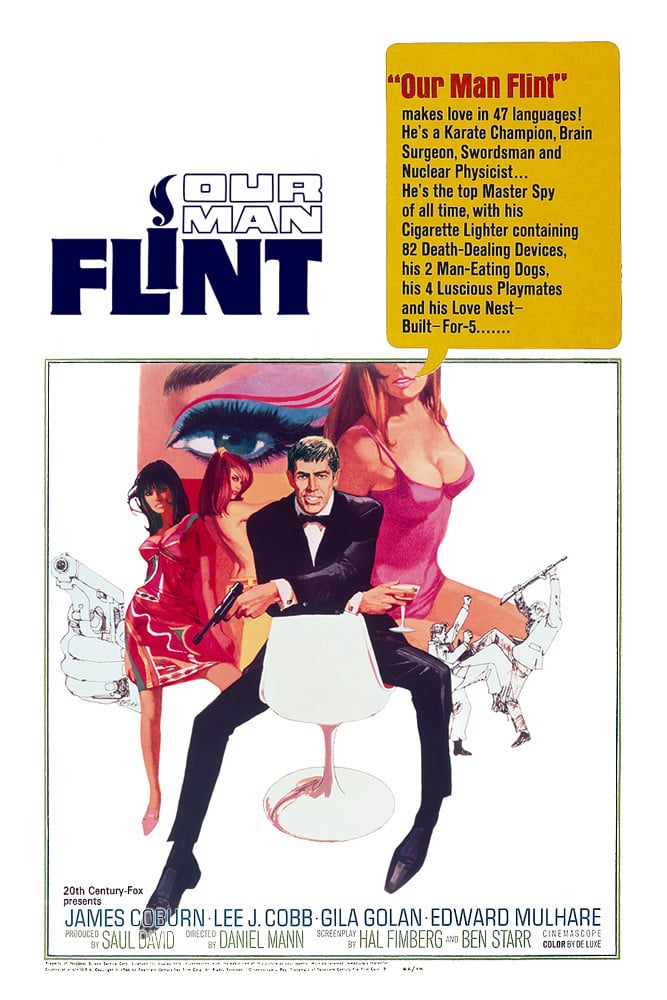

That film remains almost certainly the best-known of the '60s Bond spoofs, but not at all the first. Such films had been their own industry since 1964, though the two most important, each of them jumpstarting a mini-franchise of their own, premiered just weeks apart in January and February 1966: Our Man Flint, a glossy CinemaScope epic from 20th Century Fox, and Columbia's first Matt Helm movie, The Silencers, starring quintessential '60s icon Dean Martin. It is with the former of these pictures that we shall be concerning ourselves with at present, for no particularly better reason than the fact that I hadn't seen the movie in ages (nor had I ever seen it as many times as its slicker, more aggravating sequel, In Like Flint), and I felt like some James Coburn in my life.

Aye! James Coburn, the lanky, easygoing fella with a voice mixing gravel and honey; a character actor who had enlivened a cluster of top-drawer movies in the early '60s (most notably, to my tastes, in The Magnificent Seven and Charade), and who got his very first shot at stardom in the form of Derek Flint, American intelligence officer and all-around flawless genius. Coburn did, in fact, become a pretty gosh-darn big star for a while after this movie, and he deserved it: along with Steve McQueen and Alain Delon, he is arguably the very embodiment of all the things that go into Sixties Cool, that mixture of wit and smugness and irrepressible charisma that says in one breath "I am so much a better person than you that it's sickening" and in the next, "but you could never think of disliking me".

It's a good thing too, since Our Man Flint basically coasts along on two things: Coburn's incredible charm, and the dazzlement of a film that plays like it was built from the ground up to capture everything aesthetically and socially that defined 1965, and preserve it for the delectation of future viewers. The latter of these was presumably not a good selling point in 1966, which makes the actor's role in all this even more important, and reduces the film to one simple equation: do we, in point of fact, believe this smiling, laid-back man when he does things typical of the most absurdly confident and competent super-spy who has ever lived?

Yes we do (or rather, yes I do, and I have control of the editorial "we" at the moment), especially because Coburn deliberately underplays everything, as he would not continue to do in In Like Flint: being incredibly great at everything is something so boring to him that it never occurs to him to emphasise it, to the audience or the other characters. One of my favorite moments in his performance is in response to the suggestion that he flew to Moscow to watch a ballet performance: "No, to teach!" retorts Flint sharply, but the moment isn't played at all in the ha-ha-look-at-me-I'm-great register in which the line would appear to be written; Coburn's reaction is rather of light annoyance, the way you or I might say "I just ran to buy milk!" if someone asked whether we picked up any printer paper while we were out.

That is, incidentally, a pretty standard example of the humor in Our Man Flint, which consists almost entirely of stressing over and over and over again how amazing Flint is, and how tiring all this awesomeness is to his on-again, off-again superior officer Cramden (Lee J. Cobb, giving the only other memorable performance in the film; but do we expect less of Lee J. Cobb?). As parody, this is not in the line of its most famous descendant, Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery (that film and its sequels pay several small tributes to Flint, including the affectionate theft of a particularly obvious sound cue), mocking the idea of Bond while executing a generally broad farce; it is the specific 1960s version of Bond as lover of the high life and ruthless machine that Flint makes fun of, with a handful of specific references to Bondology (the Walther PPK, gadgets, SPECTRE) that all share the same punchline: Flint is much too perfect to need Bond's weapon/fear Bond's arch-enemy, and so forth. The same punchline, in essence, of the rest of the movie.

For a film to gamble everything on one single joke is usually suicidal: Our Man Flint manages to survive it because Coburn sells it so well, and because the film anyway isn't really as much fun as a comedy as it is a '60s lifestyle piece. Oh, there's a plot in there: it involves the international criminal group Galaxy blackmailing the world by controlling the weather and volcanoes, and the Zonal Organization for World Intelligence and Espionage (Z.O.W.I.E. - a gag that fits in with the film's overall tone not at all) sending in Flint, over Cramden's objections, to save the day. But the plot is even more immaterial than the jokes are: it is absolutely clear that Flint is never in actual danger, and he seems quite aware of it.

Instead, what makes the film so fun - and it is a hell of a lot of fun, if you can get past some of the terrifying sexual politics on display, primarily involving Flint's harem (there's no other word for it) - this too is made worse, far worse, in In Like Flint - is the hanging-out, the settling in and watching Flint be Flint in glitzy places. If I might get back to my first point, about how weird the '60s were: this was, essentially, a subgenre of cinema in those days, films where plot, action, jokes, character, and anything else like that took a back seat to being, well, cool. Not in a lifestyle porn sort of way; just in the sense that cool people and cool sets just kind of sashay back and forth and it's lighthearted without being funny and thrilling without having momentum. Our Man Flint has always seemed, in fact, to owe its biggest debt not to the Bond franchise, but to The Pink Panther with a couple gags snatched from that film's first sequel, A Shot in the Dark), a slapstick comedy that doesn't waste much energy on slapstick or comedy, a jewel heist movie that forgets about the jewel for roughly 60% of the running time. Both films are ultimately about attitude, a kind of self-satisfied ribbing of the rich and famous that also spends all the time it can staring at their trappings.

It's a style of anti-storytelling that crosses genres and countries; listing examples would be stupid, but for some reason, there was a chunk of time in which dozens of filmmakers seemed compelled to spend time dawdling with the elite. This is almost the exact equivalent of the great '30s escapist comedies, only the high society is younger and hipper, and the film's don't care if they're "funny" as long as they romp along; and to the viewer who finds (as the blogger will admit to, and without a single twitch of shame) that the mid-'60s are just about the most visually fascinating period in the post-WWII western world, the best of them are treasure chests of magnificently dated concepts and images and I'm tempted, in fact, to call Our Man Flint one of the best of them - Flint's pad, which switches from a display of tasteful nudes to tasteful abstractions at the flip of a switch, could only have come from this exact period, so could the go-go room in the villains' lair (yes, a go-go room in the villains' lair).

It's all thankfully director-proof; I am sure it could not be as cheap as director Daniel Mann and cinematographer Daniel L. Fapp make it look, because as it is, it's hardly glossier than a first season Star Trek episode. To a degree, this works to the film's benefit: without any particular artistry to give the film its own personality, nothing distorts its time capsule quality (in fact, the only behind-the-camera artist whose work rises above the completely adequate is composer Jerry Goldsmith, writing the first truly exceptional score of his legendary career, a slinky piece of sassy action funk with a main theme that is instantly recognisable even if you've never heard it). This is, unquestionably, not one for the ages. It is one for a single age only: playfully incorporating Cold War paranoia, incipient sexism, and hyper-masculine efficiency - at times, Our Man Flint seems to mock its hero, at times to fully endorse every retrograde thing he represents - and setting it all against a nonstop stream of glowing Space Age colors and shapes, the film speaks to the modern day in not the smallest respect, and everything about it seems to come from another species, let alone another era. Yet there's still that irreducible core of Cool that remains even underneath all those dated trappings, and makes the film a giddy watch even if the sheer 1965-ness of it weren't sociologically fascinating all on its own.

The 1960s were, all in all, a really damn weird time for pop culture. The Space Age, the Jet Set, the nascent Sexual Revolution, set the stage for pretty much the all-time coolest era of all time between, roughly, 1960 and 1967: when popular culture featured the Rat Pack, the British Invasion, Jean-Luc Godard's early funny ones, Fellini's period of greatest popularity, et al ad nauseum. It could only have been in this bubbling pool of arch-coolness and expanding sexual openness that world cinema could have been graced by the screen debut of British spy James Bond, a hyper-competent, hyper-masculine hero who was first introduced in the early '50s in print, though it seems kind of hard if not impossible to imagine his cinematic persona coming into existence much earlier than 1962, when director Terence Young's Dr. No turned Ian Fleming's brutally efficient, womanising spy into a brutally efficient, womanising spy and hardcore epicure (the film Bond's noted love of fine alcohol, clothes, and the luxury lifestyle being noted an extension of Young's own preoccupations).

The Bond pictures were a huge success, and like any huge success spawned immediate spoofs and imitations. The Italian film industry, for example, was essentially running of the proceeds of Bond knock-offs for several years, while English-language producers on both sides of the Atlantic were quick to come up with glamorous spy narratives of their own, from the intensely sober (as 1965's The Spy Who Came in from the Cold) to the less-sober - such as the hallucinatory 1967 Casino Royale, which is indeed the opposite of sober by just about every definition of the word.

That film remains almost certainly the best-known of the '60s Bond spoofs, but not at all the first. Such films had been their own industry since 1964, though the two most important, each of them jumpstarting a mini-franchise of their own, premiered just weeks apart in January and February 1966: Our Man Flint, a glossy CinemaScope epic from 20th Century Fox, and Columbia's first Matt Helm movie, The Silencers, starring quintessential '60s icon Dean Martin. It is with the former of these pictures that we shall be concerning ourselves with at present, for no particularly better reason than the fact that I hadn't seen the movie in ages (nor had I ever seen it as many times as its slicker, more aggravating sequel, In Like Flint), and I felt like some James Coburn in my life.

Aye! James Coburn, the lanky, easygoing fella with a voice mixing gravel and honey; a character actor who had enlivened a cluster of top-drawer movies in the early '60s (most notably, to my tastes, in The Magnificent Seven and Charade), and who got his very first shot at stardom in the form of Derek Flint, American intelligence officer and all-around flawless genius. Coburn did, in fact, become a pretty gosh-darn big star for a while after this movie, and he deserved it: along with Steve McQueen and Alain Delon, he is arguably the very embodiment of all the things that go into Sixties Cool, that mixture of wit and smugness and irrepressible charisma that says in one breath "I am so much a better person than you that it's sickening" and in the next, "but you could never think of disliking me".

It's a good thing too, since Our Man Flint basically coasts along on two things: Coburn's incredible charm, and the dazzlement of a film that plays like it was built from the ground up to capture everything aesthetically and socially that defined 1965, and preserve it for the delectation of future viewers. The latter of these was presumably not a good selling point in 1966, which makes the actor's role in all this even more important, and reduces the film to one simple equation: do we, in point of fact, believe this smiling, laid-back man when he does things typical of the most absurdly confident and competent super-spy who has ever lived?

Yes we do (or rather, yes I do, and I have control of the editorial "we" at the moment), especially because Coburn deliberately underplays everything, as he would not continue to do in In Like Flint: being incredibly great at everything is something so boring to him that it never occurs to him to emphasise it, to the audience or the other characters. One of my favorite moments in his performance is in response to the suggestion that he flew to Moscow to watch a ballet performance: "No, to teach!" retorts Flint sharply, but the moment isn't played at all in the ha-ha-look-at-me-I'm-great register in which the line would appear to be written; Coburn's reaction is rather of light annoyance, the way you or I might say "I just ran to buy milk!" if someone asked whether we picked up any printer paper while we were out.

That is, incidentally, a pretty standard example of the humor in Our Man Flint, which consists almost entirely of stressing over and over and over again how amazing Flint is, and how tiring all this awesomeness is to his on-again, off-again superior officer Cramden (Lee J. Cobb, giving the only other memorable performance in the film; but do we expect less of Lee J. Cobb?). As parody, this is not in the line of its most famous descendant, Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery (that film and its sequels pay several small tributes to Flint, including the affectionate theft of a particularly obvious sound cue), mocking the idea of Bond while executing a generally broad farce; it is the specific 1960s version of Bond as lover of the high life and ruthless machine that Flint makes fun of, with a handful of specific references to Bondology (the Walther PPK, gadgets, SPECTRE) that all share the same punchline: Flint is much too perfect to need Bond's weapon/fear Bond's arch-enemy, and so forth. The same punchline, in essence, of the rest of the movie.

For a film to gamble everything on one single joke is usually suicidal: Our Man Flint manages to survive it because Coburn sells it so well, and because the film anyway isn't really as much fun as a comedy as it is a '60s lifestyle piece. Oh, there's a plot in there: it involves the international criminal group Galaxy blackmailing the world by controlling the weather and volcanoes, and the Zonal Organization for World Intelligence and Espionage (Z.O.W.I.E. - a gag that fits in with the film's overall tone not at all) sending in Flint, over Cramden's objections, to save the day. But the plot is even more immaterial than the jokes are: it is absolutely clear that Flint is never in actual danger, and he seems quite aware of it.

Instead, what makes the film so fun - and it is a hell of a lot of fun, if you can get past some of the terrifying sexual politics on display, primarily involving Flint's harem (there's no other word for it) - this too is made worse, far worse, in In Like Flint - is the hanging-out, the settling in and watching Flint be Flint in glitzy places. If I might get back to my first point, about how weird the '60s were: this was, essentially, a subgenre of cinema in those days, films where plot, action, jokes, character, and anything else like that took a back seat to being, well, cool. Not in a lifestyle porn sort of way; just in the sense that cool people and cool sets just kind of sashay back and forth and it's lighthearted without being funny and thrilling without having momentum. Our Man Flint has always seemed, in fact, to owe its biggest debt not to the Bond franchise, but to The Pink Panther with a couple gags snatched from that film's first sequel, A Shot in the Dark), a slapstick comedy that doesn't waste much energy on slapstick or comedy, a jewel heist movie that forgets about the jewel for roughly 60% of the running time. Both films are ultimately about attitude, a kind of self-satisfied ribbing of the rich and famous that also spends all the time it can staring at their trappings.

It's a style of anti-storytelling that crosses genres and countries; listing examples would be stupid, but for some reason, there was a chunk of time in which dozens of filmmakers seemed compelled to spend time dawdling with the elite. This is almost the exact equivalent of the great '30s escapist comedies, only the high society is younger and hipper, and the film's don't care if they're "funny" as long as they romp along; and to the viewer who finds (as the blogger will admit to, and without a single twitch of shame) that the mid-'60s are just about the most visually fascinating period in the post-WWII western world, the best of them are treasure chests of magnificently dated concepts and images and I'm tempted, in fact, to call Our Man Flint one of the best of them - Flint's pad, which switches from a display of tasteful nudes to tasteful abstractions at the flip of a switch, could only have come from this exact period, so could the go-go room in the villains' lair (yes, a go-go room in the villains' lair).

It's all thankfully director-proof; I am sure it could not be as cheap as director Daniel Mann and cinematographer Daniel L. Fapp make it look, because as it is, it's hardly glossier than a first season Star Trek episode. To a degree, this works to the film's benefit: without any particular artistry to give the film its own personality, nothing distorts its time capsule quality (in fact, the only behind-the-camera artist whose work rises above the completely adequate is composer Jerry Goldsmith, writing the first truly exceptional score of his legendary career, a slinky piece of sassy action funk with a main theme that is instantly recognisable even if you've never heard it). This is, unquestionably, not one for the ages. It is one for a single age only: playfully incorporating Cold War paranoia, incipient sexism, and hyper-masculine efficiency - at times, Our Man Flint seems to mock its hero, at times to fully endorse every retrograde thing he represents - and setting it all against a nonstop stream of glowing Space Age colors and shapes, the film speaks to the modern day in not the smallest respect, and everything about it seems to come from another species, let alone another era. Yet there's still that irreducible core of Cool that remains even underneath all those dated trappings, and makes the film a giddy watch even if the sheer 1965-ness of it weren't sociologically fascinating all on its own.