Head full of zombie

It has for some time been my custom to celebrate Easter by diving into a zombie movie or four; the problem is that there are precious few important zombie franchises and I've already reviewed most of them; also that once you get past the tip-top of the A-list of the subgenre, a disquieting and dispiriting sameness infects most of the lesser - often much lesser - zombie films. In the interests of keeping things fresh, I've decided to do something just a bit different this year: rather than scrounging up some other damn Italian or independent American gorefest to poke at for a few weeks, I'm going to take a look at a pair of films from the very dawn of zombies in the movies, before George A. Romero introduced the notion of gutmunching cannibal undead to the horror film lexicon.

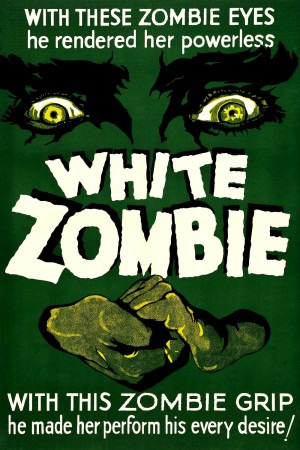

In fact, the first of these films, White Zombie of 1932, almost certainly holds the honor of being the very first zombie picture ever made. Back in those days, the very word "zombie" was new and bold and exotic; the standard histories tell us that the word was introduced to nice, regular Americans in a 1929 pulp novel, The Magic Island, in which a visitor to Haiti is terrorised by a voodoo cult. Whatever the specific details, it is certainly the case that around the turn of the 1930s, the idea of wicked Caribbean witch doctors had just taken firm hold on the pop culture consciousness; and since this was also the same time that the one-two punch of Universal's Dracula and Frankenstein, in 1931, broke down the longstanding taboo against paranormal horror films in America, it was probably inevitable that somebody would hit upon the idea of combining the two, and soon.

The men who got there first were brothers Edward and Victor Halperin, respectively a producer and director of low-budget pictures; mostly romances to that point, but they knew a good idea when they saw it, and kicked off the second, final phase of their career as horror filmmakers. Armed with a scant $50,000 - not the pocket change in 1932 it would be today, but still hardly enough to make any kind of decent-sized production - the Halperins started another longstanding tradition by renting Universal's own Dracula and Frankenstein sets and thereby giving their White Zombie a sheen of prestige they couldn't otherwise afford. They also managed to pick up Universal's Dracula star, casting Bela Lugosi in the role of their film's villain, a white voodoo mastermind with the eminently unforgettable name Murder Legendre. This was Lugosi's first indie production after breaking through, which makes this, in its own way, the first definite step on a path that would lead ultimately to Bela Lugosi Meets a Brooklyn Gorilla and the posthumous shame of Plan 9 from Outer Space. A truly depressing legacy for what would be, despite the cheap, rushed context in which it was delivered, one of the absolute pinnacle performances of Lugosi's career, and I would not choose to fight with anybody who wanted to call Murder Legendre his all-time best work.

Nor do I think you'd find many people willing to disagree that Lugosi is the best part of White Zombie, which makes it unfortunate that he's actually only the fourth-most important character in the plot, despite top billing. In cold reality, the film largely belongs to Madeline Short (Madge Bellamy) and Neil Parker (John Harron), a young couple just arriving on Haiti, where they are to be married. Apparently, Madeline once caught the eye of a landowner, one Charles Beaumont (Robert Frazer), who was so eager to help her and her fiancé out that he gave Neil a job, and further offered to pay for their wedding at his Haitian plantation, where they could jump right into a tropical honeymoon after the ceremony.

If that sounds vaguely suspicious, it should: once the lovers arrive at Beaumonts, they are told by local priest Dr. Bruner (Joseph Cawthorn) in no uncertain terms that their host is dangerous, though even Bruner doesn't know that the reason Beaumont has arranged for the wedding to be in his own backyard is because he hopes to break up the couple and marry Madeline himself. And the only way that will happen is if Beaumont can convince the local sugar baron and voodoo king, Legendre, to use some magic on the girl. What Legendre does is rather far from a simple love potion: he arranges to poison Madeline with his zombie powder, leaving her apparently dead mere hours after the wedding, but animate and under the control of Legendre's telepathy. This naturally doesn't sit well with Beaumont, who wanted a fully living bride of his own, but when he confronts the voodoo man, it turns out - unsurprisingly - that Legendre has more plans than Beaumont had planned for. And about this time, Neil makes the intensely unsettling discovery that his dead wife is no longer in the coffin.

White Zombie, being as it is a B-movie from 1932, sails in at a stately 66 minutes, by which point some of the more indulgent latter-day zombie films haven't even introduced their own revenants. It's also a top-notch example of why deep down inside, I will never like contemporary cinema as much as I do '30s cinema; for with that kind of running time and a fully-loaded plot to deal with, Victor Halperin and screenwriter Garnett Weston simply do not have time to dick around. It might strike a modern viewer, raised on a steady diet of Night of the Living Dead copies, as annoyingly slow-paced and dismayingly free of gory deaths, but White Zombie is a lean beast, wasting nothing - even the opening credits are over the opening action of the film, and not title cards, a massive shock for the era. We need exposition? BAM - it comes in one crisply-expressed speech at the very top of the movie. We need a sense of foreboding? BAM - it comes right after the exposition, as the couple's couch is stopped by a funeral right in the middle of the damn road, explained by the coachman (Clarence Muse, the only prominent African-American in this Haiti-set movie, though given a role that, by '32 standards, is freakishly unconcerned with the color of his skin) to be part of a ritual whereby the locals attempt to ensure the bodies of the deceased can't come back. Need a creepy-ass villain? BAM - no sooner have Madeline and Neil laughed this quaint custom off than they drive past Legendre, flanked by a team of uncomfortably mute, staring associates, who gazes at Madeline with a soul-blanching wickedness that only Bela Lugosi at his very best could ever have expressed, ending when the voodoo man has snatched the young bride's scarf, promising very bad things to come.

So all praise be to efficiency; but that doesn't mean that the Halperins and crew are trying to blitz through the film and get it over with. On the contrary, White Zombie is marked by a pronounced willingness to linger on disquieting atmospheric moments, with cinematographer Arthur Martinelli capturing sequences like Gothic paintings, eerie and tableau-like (what does it say that two nobodies like Martinelli and Victor Halperin were able to do more evocative things with the Dracula sets than Tod Browning and Karl Freund?). No modern viewer can possibly be as creeped out by the mere fact of animate corpses as people were in the '30s, but even still something remains of the ethereal unholiness of Halperin and Martinelli's pointed, slightly diffuse shots of zombies just... standing there, gaping without changing their expressions in the slightest. Or, in what is perhaps the film's best-known scene, we follow Beaumont as he gets the tour of Legendre's sugar mill, staffed by zombies: in one incredible shot, the undead shuffle around the mill, driving its gears, making no sound except the rhythmic creak of the blades chopping sugar cane (the sound in this scene, and in fact at points throughout the movie, is wildly sophisticated for a cheap-as-hell horror flick in 1932). This is followed by a shot of a zombie stumbling, mutely, into the mill, right onto those same steady blades - we don't see anything, of course, but the unearthly silence of this whole sequence, except the creak, creak, creak of the blades, gives the sequence a kick that 80 years aren't enough to dilute.

White Zombie isn't exactly Expressionistic, the default mode for most paranormal and mock-paranormal American horror in that decade; the style of White Zombie is something akin but necessarily different, something more gauzy and less visually aggressive but no less nightmarish. The film creates atmosphere like nothing else, and that is part of why it remains a horror classic generations after audiences embraced it with moderate enthusiasm and critics lambasted it. The visual mood, and the incredible aura projected by Lugosi, whose eyes control all of the action in the film, and did any actor have eyes better suited to the task? Especially with the light being focused right in his eye sockets, giving him an intense look even by his own standards. There's a moment where just his eyes are superimposed over the action, floating and hovering and flying: it would be stupid as shit if it weren't so uncanny. Even with a stupid-ass beard, Lugosi can command the camera with nothing but his carnivorous grin and the unnerving way he wrings his hands as he controls his victims: it's overacting and then some, but Lugosi always had a habit of making overacting look perfect.

This trait is not, unfortunately, shared by his castmates: for though White Zombie is beautiful and anchored by a god-damned triumph of a performance, it's held back by a cast of the most alarmingly inert non-entities you could hope to see in a '30s quickie. Bellamy, a silent film star who had a rough time in the sound era, comes off the worst: even through the shaky sound quality that has come down to us through the ages, her line-readings are painfully flat, and her expressions curiously unchanging. It's no accident that she's at her best playing a braindead subhuman, where her silent film training actually comes into some use. Frazer and Harron at least are better than she is, but neither makes much of an impression; Frazer does get one outstanding scene where he realises just how badly Legendre has screwed him over, but in the main the lead males generally stand with gently bemused looks on their faces, with Harron descending into a banal succession of "this is my sad face" moments, leavened only by his occasional outbursts of terror. Neither man is remotely enough to hold the screen against Lugosi, though better actors than they have failed.

The complete disintegration of every non-Lugosi performer and every non-Legendre character leaves White Zombie in a curious fix: the best moments are absolutely as great as anything else you will ever see in '30s horror, but the rest - that is to say, the majority - is staid and undernourished, exactly the stereotype that young people have of early sound cinema. Luckily, horror fans know how to take the good with the very bad, and White Zombie shines through its own failings; but how much better it would be if it didn't have to, if this minor horror classic were instead an all-time genre masterpiece. It comes close, though, and set a standard that virtually none of the subsequent "voodoo zombie" films of the next three decades came near to meeting.

In fact, the first of these films, White Zombie of 1932, almost certainly holds the honor of being the very first zombie picture ever made. Back in those days, the very word "zombie" was new and bold and exotic; the standard histories tell us that the word was introduced to nice, regular Americans in a 1929 pulp novel, The Magic Island, in which a visitor to Haiti is terrorised by a voodoo cult. Whatever the specific details, it is certainly the case that around the turn of the 1930s, the idea of wicked Caribbean witch doctors had just taken firm hold on the pop culture consciousness; and since this was also the same time that the one-two punch of Universal's Dracula and Frankenstein, in 1931, broke down the longstanding taboo against paranormal horror films in America, it was probably inevitable that somebody would hit upon the idea of combining the two, and soon.

The men who got there first were brothers Edward and Victor Halperin, respectively a producer and director of low-budget pictures; mostly romances to that point, but they knew a good idea when they saw it, and kicked off the second, final phase of their career as horror filmmakers. Armed with a scant $50,000 - not the pocket change in 1932 it would be today, but still hardly enough to make any kind of decent-sized production - the Halperins started another longstanding tradition by renting Universal's own Dracula and Frankenstein sets and thereby giving their White Zombie a sheen of prestige they couldn't otherwise afford. They also managed to pick up Universal's Dracula star, casting Bela Lugosi in the role of their film's villain, a white voodoo mastermind with the eminently unforgettable name Murder Legendre. This was Lugosi's first indie production after breaking through, which makes this, in its own way, the first definite step on a path that would lead ultimately to Bela Lugosi Meets a Brooklyn Gorilla and the posthumous shame of Plan 9 from Outer Space. A truly depressing legacy for what would be, despite the cheap, rushed context in which it was delivered, one of the absolute pinnacle performances of Lugosi's career, and I would not choose to fight with anybody who wanted to call Murder Legendre his all-time best work.

Nor do I think you'd find many people willing to disagree that Lugosi is the best part of White Zombie, which makes it unfortunate that he's actually only the fourth-most important character in the plot, despite top billing. In cold reality, the film largely belongs to Madeline Short (Madge Bellamy) and Neil Parker (John Harron), a young couple just arriving on Haiti, where they are to be married. Apparently, Madeline once caught the eye of a landowner, one Charles Beaumont (Robert Frazer), who was so eager to help her and her fiancé out that he gave Neil a job, and further offered to pay for their wedding at his Haitian plantation, where they could jump right into a tropical honeymoon after the ceremony.

If that sounds vaguely suspicious, it should: once the lovers arrive at Beaumonts, they are told by local priest Dr. Bruner (Joseph Cawthorn) in no uncertain terms that their host is dangerous, though even Bruner doesn't know that the reason Beaumont has arranged for the wedding to be in his own backyard is because he hopes to break up the couple and marry Madeline himself. And the only way that will happen is if Beaumont can convince the local sugar baron and voodoo king, Legendre, to use some magic on the girl. What Legendre does is rather far from a simple love potion: he arranges to poison Madeline with his zombie powder, leaving her apparently dead mere hours after the wedding, but animate and under the control of Legendre's telepathy. This naturally doesn't sit well with Beaumont, who wanted a fully living bride of his own, but when he confronts the voodoo man, it turns out - unsurprisingly - that Legendre has more plans than Beaumont had planned for. And about this time, Neil makes the intensely unsettling discovery that his dead wife is no longer in the coffin.

White Zombie, being as it is a B-movie from 1932, sails in at a stately 66 minutes, by which point some of the more indulgent latter-day zombie films haven't even introduced their own revenants. It's also a top-notch example of why deep down inside, I will never like contemporary cinema as much as I do '30s cinema; for with that kind of running time and a fully-loaded plot to deal with, Victor Halperin and screenwriter Garnett Weston simply do not have time to dick around. It might strike a modern viewer, raised on a steady diet of Night of the Living Dead copies, as annoyingly slow-paced and dismayingly free of gory deaths, but White Zombie is a lean beast, wasting nothing - even the opening credits are over the opening action of the film, and not title cards, a massive shock for the era. We need exposition? BAM - it comes in one crisply-expressed speech at the very top of the movie. We need a sense of foreboding? BAM - it comes right after the exposition, as the couple's couch is stopped by a funeral right in the middle of the damn road, explained by the coachman (Clarence Muse, the only prominent African-American in this Haiti-set movie, though given a role that, by '32 standards, is freakishly unconcerned with the color of his skin) to be part of a ritual whereby the locals attempt to ensure the bodies of the deceased can't come back. Need a creepy-ass villain? BAM - no sooner have Madeline and Neil laughed this quaint custom off than they drive past Legendre, flanked by a team of uncomfortably mute, staring associates, who gazes at Madeline with a soul-blanching wickedness that only Bela Lugosi at his very best could ever have expressed, ending when the voodoo man has snatched the young bride's scarf, promising very bad things to come.

So all praise be to efficiency; but that doesn't mean that the Halperins and crew are trying to blitz through the film and get it over with. On the contrary, White Zombie is marked by a pronounced willingness to linger on disquieting atmospheric moments, with cinematographer Arthur Martinelli capturing sequences like Gothic paintings, eerie and tableau-like (what does it say that two nobodies like Martinelli and Victor Halperin were able to do more evocative things with the Dracula sets than Tod Browning and Karl Freund?). No modern viewer can possibly be as creeped out by the mere fact of animate corpses as people were in the '30s, but even still something remains of the ethereal unholiness of Halperin and Martinelli's pointed, slightly diffuse shots of zombies just... standing there, gaping without changing their expressions in the slightest. Or, in what is perhaps the film's best-known scene, we follow Beaumont as he gets the tour of Legendre's sugar mill, staffed by zombies: in one incredible shot, the undead shuffle around the mill, driving its gears, making no sound except the rhythmic creak of the blades chopping sugar cane (the sound in this scene, and in fact at points throughout the movie, is wildly sophisticated for a cheap-as-hell horror flick in 1932). This is followed by a shot of a zombie stumbling, mutely, into the mill, right onto those same steady blades - we don't see anything, of course, but the unearthly silence of this whole sequence, except the creak, creak, creak of the blades, gives the sequence a kick that 80 years aren't enough to dilute.

White Zombie isn't exactly Expressionistic, the default mode for most paranormal and mock-paranormal American horror in that decade; the style of White Zombie is something akin but necessarily different, something more gauzy and less visually aggressive but no less nightmarish. The film creates atmosphere like nothing else, and that is part of why it remains a horror classic generations after audiences embraced it with moderate enthusiasm and critics lambasted it. The visual mood, and the incredible aura projected by Lugosi, whose eyes control all of the action in the film, and did any actor have eyes better suited to the task? Especially with the light being focused right in his eye sockets, giving him an intense look even by his own standards. There's a moment where just his eyes are superimposed over the action, floating and hovering and flying: it would be stupid as shit if it weren't so uncanny. Even with a stupid-ass beard, Lugosi can command the camera with nothing but his carnivorous grin and the unnerving way he wrings his hands as he controls his victims: it's overacting and then some, but Lugosi always had a habit of making overacting look perfect.

This trait is not, unfortunately, shared by his castmates: for though White Zombie is beautiful and anchored by a god-damned triumph of a performance, it's held back by a cast of the most alarmingly inert non-entities you could hope to see in a '30s quickie. Bellamy, a silent film star who had a rough time in the sound era, comes off the worst: even through the shaky sound quality that has come down to us through the ages, her line-readings are painfully flat, and her expressions curiously unchanging. It's no accident that she's at her best playing a braindead subhuman, where her silent film training actually comes into some use. Frazer and Harron at least are better than she is, but neither makes much of an impression; Frazer does get one outstanding scene where he realises just how badly Legendre has screwed him over, but in the main the lead males generally stand with gently bemused looks on their faces, with Harron descending into a banal succession of "this is my sad face" moments, leavened only by his occasional outbursts of terror. Neither man is remotely enough to hold the screen against Lugosi, though better actors than they have failed.

The complete disintegration of every non-Lugosi performer and every non-Legendre character leaves White Zombie in a curious fix: the best moments are absolutely as great as anything else you will ever see in '30s horror, but the rest - that is to say, the majority - is staid and undernourished, exactly the stereotype that young people have of early sound cinema. Luckily, horror fans know how to take the good with the very bad, and White Zombie shines through its own failings; but how much better it would be if it didn't have to, if this minor horror classic were instead an all-time genre masterpiece. It comes close, though, and set a standard that virtually none of the subsequent "voodoo zombie" films of the next three decades came near to meeting.