The city I live in, the city of angels

Reader Geoffrey Moses - better known as regular commenter GeoX - upon donating to the Carry On Campaign, directed me to review a movie he vaguely and ominously described as "interesting". It's at least that, a fascinatingly, willfully dysfunctional action thriller that I'd always avoided on the assumption that it was as boilerplate as it scenario. Oh my, no.

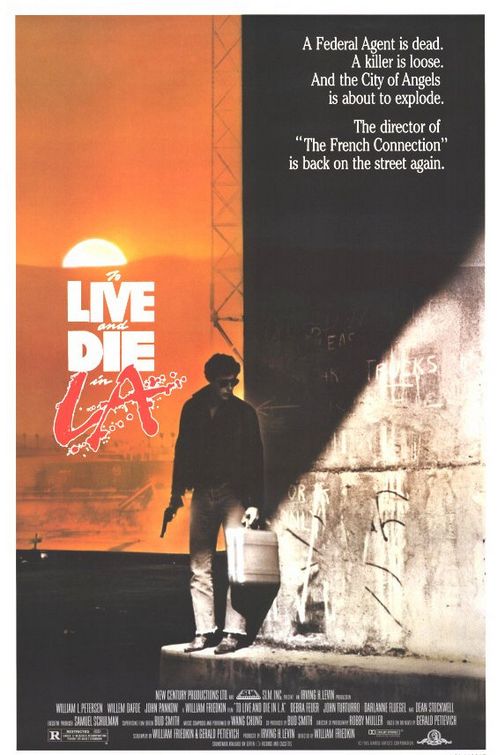

In many respects, William Friedkin's 1985 crime thriller To Live and Die in L.A. is a monumentally common '80s action picture; hell, the whole plot kicks into motion when a grizzled old veteran who announces with gravelly resignation that he's too old for this shit is murdered by a vicious crime lord just two days before retirement. If it had come out a few years later, it would be almost impossible to resist the temptation to label it a Michael Mann knock-off, with its dual-protagonist narrative and emphasis on the visual language of pop culture (I suspect Mann would agree - he unsuccessfully sued the filmmakers for stealing from Miami Vice); even without that as a touchstone, it's simply not possible to claim with a straight face that by 1985, the idea of a cop being driven into a moral and legal grey zone in his obsessive desire to catch a seemingly untouchable villain was by any stretch of the imagination a fresh story.

And yet, there's an ineffable quality about To Live and Die that isn't so easy to pin down as that. There's nothing about it that's specifically original or unconventional until the last 10 minutes, but from virtually the first scene, something is distinctly and unapologetically "off" about the movie, as though despite writing most of the screenplay (adapted from T-Man Gerald Petievich's novel, with Petievich's help) and shepherding the project from birth to completion, Friedkin wasn't actually interested in making a cop procedural at all. The narrative focus is all wrong for that, the performances are all slightly arch and stylised, and the visual style Friedkin uses, along with cinematographer Robby Müller - a frequent collaborator of Wim Wenders and later Jim Jarmusch, who shot Paris, Texas just one year before this, and what a telling fact that is - is largely more concerned with textures and the emotional feeling of a space, rather than capturing with any kind of fidelity the actual physical sense of a location. Let me put it this way: Friedkin's The French Connection is above all a story about New York, capturing that city with documentary fidelity, while To Live and Die in L.A., its title notwithstanding, only vaguely feels like it takes place anywhere in particular.

The difference, maybe, is that New York is a place of great specificity, one that even a fella who's never been can describe with some depth of feeling just based on the mythology of the city, while Los Angeles is almost by definition the city that has no inherent personality. It is famous, primarily, for being turned into other places, but by itself it is nothing but an assemblage of surfaces. In that respect, it is the exact perfect city for Secret Service agent Richard Chance (William Petersen), a man apparently without any inner self - certainly, by the time we meet him, there is nothing left of the man, only the professional. A professional, moreover, who is further denied self-definition on account once again of the city: a Treasury agent outside of Washington is in an inherently curious state (this was mainly what attracted Friedkin to the material), and whatever we might think of when we hear the words "Secret Service", those are not things true of Chance.

Chance has made a life's quest out of hunting down Eric Masters (Willem Dafoe), a particularly notorious counterfeiter who kills Chance's partner, Jim Hart (Michael Greene), following the peculiar opening sequence in which Chance and Hart save President Reagan - actual Reagan audio is used! - from a Muslim terrorist who dies in spectacularly violent fashion. Neither Reagan nor Islam makes another appearance in the film, and the opening sequence remains stirringly opaque, a disjointed piece of scene-setting that doesn't actually set the scene for anything that happens (though it does show the contrast between the in-control Chance of the first scene and the increasingly psychotic Chance of the bulk of the movie).

So, yes: angry, revenge-driven Treasury agent teamed with a meek partner (John Pankow) doing whatever it takes to bring down the bad guy, whether it's coercing his "girlfriend" Ruth (Darlanne Fluegel), whose contact with the L.A. underworld are plainly the only reason Chance spends any time with her at all, threatening Master's imprisoned lieutenant (John Turturro), or generally playing both sides of the law. You've seen this before, I've seen this before. The great appeal of To Live and Die is not the story it tells, nor even really how it is told (though Friedkin is a gifted enough filmmaker that the movie works far more often than it doesn't as a thriller), but the tone. This is a profoundly ambivalent motion picture, terrifically uncertain of its relationship to the protagonist. It's not that it grows away from Chance as he becomes more and more unethical; rather that as the film moves on it becomes increasingly disinterested in him as a character at all, culminating in a climax that oh-so-casually violates the normal rules about what an action hero does and doesn't do in the finale of his movie, completely upending every convention of its hidebound genre without even seeming to notice that it has done so.

It's the film's uncertainty about Chance, played by first-time leading man Petersen with a degree of inscrutability that might be the side-effect of poor acting (I won't deny that I have little use for the actor in general), though it undoubtedly fits the movie's program to a T. Essentially, Friedkin is doing much the same thing he attempted five years earlier in Cruising, to make a film that is specifically about how his main character fails to succeed in the narrative function he has been ascribed; if To Live and Die is massively more effective, that's largely because it abandons the toxic sociology and unfathomable obsession with and disgust towards male homosexuality that makes Cruising almost impossible to take seriously on any level. It's certainly easy to fall in love with a movie that does this much to break down its own meaning as a psychological action picture.

Would that the rest of the movie was so profoundly fascinating. Not that it's particularly bad, but To Live and Die is definitely not, on the whole, as stimulating as its treatment of its central character. The film is dominated by a concern with counterfeits: the obvious way in which the plot hinges on funny money, but more generally on the way that surfaces and realities don't match up (in that spirit, we could even say that the broken narrative and increasingly dysfunctional hero make To Live and Die a counterfeit action movie). There's quite a lot to this that is appealing and surprising, though Friedkin's treatment of this theme is maddeningly superficial, too entranced with "gotcha!" moments where he seems to be playing with the audience's perception not to make a point, but to be a dick (one particularly egregious moment: the first time we see Masters's lover, played by Debra Feuer, she's dressed as a man and it briefly seems that Masters is gay, as though Friedkin was deliberately poking fun at Cruising or something along those lines). And the not-quite equivalence of the names Masters and Chance (the one in control and the one flying about crazily) speaks to a programmatic view of the story that is not at all rewarding, and that Friedkin never quite shakes off.

It says a lot that despite being a great deal more nuanced and performed with much more technical acumen, Masters is simply not as compelling as Chance; the film is largely interesting only in its most unconventional aspects, and when it actually plays by the cop movie rules that, after all, largely drives its plot, it gets boring on us. A car chase scene that subscribes to virtually none of the editing rhythms common to the genre: fascinating and arresting. Scenes of Chance hunting down information: deadly. To Live and Die invests so much energy into breaking rules that when it follows the rules, it's not particularly successful at all, which is a paradox Friedkin probably would appreciate, though it's not much use when you're watching the thing.

There's enough left over that it doesn't entire matter, though. The film is both in its plot and its construction absolutely entranced by the appearance of things, and the result is a movie uncomfortably aware of its own position within the pop culture landscape. More than once, you get the feeling that To Live and Die was secretly made a decade or two later by people trying to make a movie that evoked The Eighties to almost comic respect; it's quite a lot like the same year's Back to the Future, in the way that it could hardly be more of a time capsule of the look and feel of a specific moment, and in the curious sense that the filmmakers were doing that on purpose. Could anything possibly communicate "1985", in color palette and content, more clearly and stereotypically than this frame from the opening credits?

It's too much to say that To Live and Die in L.A. is a great movie, but it holds up better than a lot of the movies working in the same idiom from the same time. And of course, it almost has to: it self-consciously breaks down the superficiality of that idiom by stressing its own shallowness. A brave and perhaps inherently self-defeating tack for any movie to take, but then William Friedkin was always a bit hellbent on doing what was different, and that's enough to keep this most remarkably dated motion picture fresh and provocative a quarter of a century on.

In many respects, William Friedkin's 1985 crime thriller To Live and Die in L.A. is a monumentally common '80s action picture; hell, the whole plot kicks into motion when a grizzled old veteran who announces with gravelly resignation that he's too old for this shit is murdered by a vicious crime lord just two days before retirement. If it had come out a few years later, it would be almost impossible to resist the temptation to label it a Michael Mann knock-off, with its dual-protagonist narrative and emphasis on the visual language of pop culture (I suspect Mann would agree - he unsuccessfully sued the filmmakers for stealing from Miami Vice); even without that as a touchstone, it's simply not possible to claim with a straight face that by 1985, the idea of a cop being driven into a moral and legal grey zone in his obsessive desire to catch a seemingly untouchable villain was by any stretch of the imagination a fresh story.

And yet, there's an ineffable quality about To Live and Die that isn't so easy to pin down as that. There's nothing about it that's specifically original or unconventional until the last 10 minutes, but from virtually the first scene, something is distinctly and unapologetically "off" about the movie, as though despite writing most of the screenplay (adapted from T-Man Gerald Petievich's novel, with Petievich's help) and shepherding the project from birth to completion, Friedkin wasn't actually interested in making a cop procedural at all. The narrative focus is all wrong for that, the performances are all slightly arch and stylised, and the visual style Friedkin uses, along with cinematographer Robby Müller - a frequent collaborator of Wim Wenders and later Jim Jarmusch, who shot Paris, Texas just one year before this, and what a telling fact that is - is largely more concerned with textures and the emotional feeling of a space, rather than capturing with any kind of fidelity the actual physical sense of a location. Let me put it this way: Friedkin's The French Connection is above all a story about New York, capturing that city with documentary fidelity, while To Live and Die in L.A., its title notwithstanding, only vaguely feels like it takes place anywhere in particular.

The difference, maybe, is that New York is a place of great specificity, one that even a fella who's never been can describe with some depth of feeling just based on the mythology of the city, while Los Angeles is almost by definition the city that has no inherent personality. It is famous, primarily, for being turned into other places, but by itself it is nothing but an assemblage of surfaces. In that respect, it is the exact perfect city for Secret Service agent Richard Chance (William Petersen), a man apparently without any inner self - certainly, by the time we meet him, there is nothing left of the man, only the professional. A professional, moreover, who is further denied self-definition on account once again of the city: a Treasury agent outside of Washington is in an inherently curious state (this was mainly what attracted Friedkin to the material), and whatever we might think of when we hear the words "Secret Service", those are not things true of Chance.

Chance has made a life's quest out of hunting down Eric Masters (Willem Dafoe), a particularly notorious counterfeiter who kills Chance's partner, Jim Hart (Michael Greene), following the peculiar opening sequence in which Chance and Hart save President Reagan - actual Reagan audio is used! - from a Muslim terrorist who dies in spectacularly violent fashion. Neither Reagan nor Islam makes another appearance in the film, and the opening sequence remains stirringly opaque, a disjointed piece of scene-setting that doesn't actually set the scene for anything that happens (though it does show the contrast between the in-control Chance of the first scene and the increasingly psychotic Chance of the bulk of the movie).

So, yes: angry, revenge-driven Treasury agent teamed with a meek partner (John Pankow) doing whatever it takes to bring down the bad guy, whether it's coercing his "girlfriend" Ruth (Darlanne Fluegel), whose contact with the L.A. underworld are plainly the only reason Chance spends any time with her at all, threatening Master's imprisoned lieutenant (John Turturro), or generally playing both sides of the law. You've seen this before, I've seen this before. The great appeal of To Live and Die is not the story it tells, nor even really how it is told (though Friedkin is a gifted enough filmmaker that the movie works far more often than it doesn't as a thriller), but the tone. This is a profoundly ambivalent motion picture, terrifically uncertain of its relationship to the protagonist. It's not that it grows away from Chance as he becomes more and more unethical; rather that as the film moves on it becomes increasingly disinterested in him as a character at all, culminating in a climax that oh-so-casually violates the normal rules about what an action hero does and doesn't do in the finale of his movie, completely upending every convention of its hidebound genre without even seeming to notice that it has done so.

It's the film's uncertainty about Chance, played by first-time leading man Petersen with a degree of inscrutability that might be the side-effect of poor acting (I won't deny that I have little use for the actor in general), though it undoubtedly fits the movie's program to a T. Essentially, Friedkin is doing much the same thing he attempted five years earlier in Cruising, to make a film that is specifically about how his main character fails to succeed in the narrative function he has been ascribed; if To Live and Die is massively more effective, that's largely because it abandons the toxic sociology and unfathomable obsession with and disgust towards male homosexuality that makes Cruising almost impossible to take seriously on any level. It's certainly easy to fall in love with a movie that does this much to break down its own meaning as a psychological action picture.

Would that the rest of the movie was so profoundly fascinating. Not that it's particularly bad, but To Live and Die is definitely not, on the whole, as stimulating as its treatment of its central character. The film is dominated by a concern with counterfeits: the obvious way in which the plot hinges on funny money, but more generally on the way that surfaces and realities don't match up (in that spirit, we could even say that the broken narrative and increasingly dysfunctional hero make To Live and Die a counterfeit action movie). There's quite a lot to this that is appealing and surprising, though Friedkin's treatment of this theme is maddeningly superficial, too entranced with "gotcha!" moments where he seems to be playing with the audience's perception not to make a point, but to be a dick (one particularly egregious moment: the first time we see Masters's lover, played by Debra Feuer, she's dressed as a man and it briefly seems that Masters is gay, as though Friedkin was deliberately poking fun at Cruising or something along those lines). And the not-quite equivalence of the names Masters and Chance (the one in control and the one flying about crazily) speaks to a programmatic view of the story that is not at all rewarding, and that Friedkin never quite shakes off.

It says a lot that despite being a great deal more nuanced and performed with much more technical acumen, Masters is simply not as compelling as Chance; the film is largely interesting only in its most unconventional aspects, and when it actually plays by the cop movie rules that, after all, largely drives its plot, it gets boring on us. A car chase scene that subscribes to virtually none of the editing rhythms common to the genre: fascinating and arresting. Scenes of Chance hunting down information: deadly. To Live and Die invests so much energy into breaking rules that when it follows the rules, it's not particularly successful at all, which is a paradox Friedkin probably would appreciate, though it's not much use when you're watching the thing.

There's enough left over that it doesn't entire matter, though. The film is both in its plot and its construction absolutely entranced by the appearance of things, and the result is a movie uncomfortably aware of its own position within the pop culture landscape. More than once, you get the feeling that To Live and Die was secretly made a decade or two later by people trying to make a movie that evoked The Eighties to almost comic respect; it's quite a lot like the same year's Back to the Future, in the way that it could hardly be more of a time capsule of the look and feel of a specific moment, and in the curious sense that the filmmakers were doing that on purpose. Could anything possibly communicate "1985", in color palette and content, more clearly and stereotypically than this frame from the opening credits?

It's too much to say that To Live and Die in L.A. is a great movie, but it holds up better than a lot of the movies working in the same idiom from the same time. And of course, it almost has to: it self-consciously breaks down the superficiality of that idiom by stressing its own shallowness. A brave and perhaps inherently self-defeating tack for any movie to take, but then William Friedkin was always a bit hellbent on doing what was different, and that's enough to keep this most remarkably dated motion picture fresh and provocative a quarter of a century on.

Categories: action, carry on campaign, crime pictures, thrillers, violence and gore