The 46th Chicago International Film Festival

I would dearly love, just once, to see a French movie that depicts sex as a warm, joyful experience, one that leaves all participants feeling fulfilled and better about themselves and life. But that day is probably never going to come, and as long as the country's filmmakers would rather depict sex as a twisted, difficult, even traumatic experience, we could be a whole lot less fortunate than to keep getting films as accomplished as Love Like Poison, the unnervingly certain feature debut of director Katell Quillévéré, whom I will henceforth refer to as "the director", not to diminish her outstanding achievement in any way, but because it takes me about a minute every time I type "Quillévéré" to make certain that I got the accents all right.

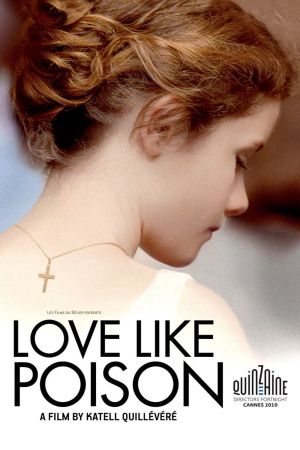

The film - whose French title, Un poison violent, means something extremely different than its English title, though they both reference the same Serge Gainsbourg song - is the story of the coming-of-age of Anna (Clara Augarde), a teenage girl attending Catholic boarding school who has returned to her tiny village for a brief while. It is not a pleasant while: her mother, Jeanne (Lio), announces that she and Anna's father (Thierry Neuvic) are divorcing, and he has fled; though he's left his father, Jean (Michel Galabru) behind for Jeanne to take care of. Nor is this the only, or even the biggest, crisis in Anna's life: as she prepares for her confirmation - a moment of profound importance for a good Catholic girl raised by as domineering and religious a mother as Jeanne plainly is - she is aware both of an increasing sense of spiritual panic, convinced that she's just not faithful enough, and the rising tide of libido common to all young teenagers. And the tension between the two is more or less killing her.

Incident is not high on the director's list of priorities (she also wrote the screenplay, in collaboration with Mariette Désert): Love Like Poison is, to the exclusion of virtually all else, a depiction of personality. Anna's, chiefly, although there is a B-plot almost as rich in character detail involving Jeanne's growing dependence on the young new parish priest, Father François (Stefano Cassetti), whose cloudy eyes and distinctly Italian features may or may not inspire something akin to lust in the devout woman's heart, though it's far less ambiguous that he's feeling something extremely akin to lust for her. If there's a message in all of this, it's "religion creates a diseased impression of sexuality", but a polemic isn't really in the director's field of vision, either.

The film is breathtakingly subtle, presenting a number of challenging situations and allowing them to play out without comment, other than what we bring to the film as an audience. This is probably best seen in the matter of Anna and her grandfather: Jean, bedridden, corpulent, and crummy, is a high-spirited old pervert, blithely observant of his granddaughter's nubility, and yet he's also the closest she knows to a genuinely kindly soul. Part of us wants to hate and condemn him; part of us is thankful that he's there, for without him, it's difficult to say what Anna would know of familial love.

Perhaps even more unsettling than this, is the director's willing sexualisation of Anna's body - Augarde being all of 14 when the film was shot, it's almost terrifying when we see her bare breasts on camera, and when she subsequently accuses her mother (who has been spying on her naked daughter for reasons that are probably focused on her own jealousy of the girl's innocence), "Do I turn you on?" she's framed to look almost directly at the camera, a forthright challenge to the audience, or at least the part of the audience that likes naked women. In fact, the awareness of cinema's default male gaze, and the deliberate attempt to exploit and break that gaze, is a key part of the director's visual depiction of her protagonist. "Do I turn you on?" is asked, implicitly, in much of the film, and the director plainly has little respect for anyone who would respond, "yes". But I do not want to belabor this, for these issues are still less important than the exploration of character per se, which in this case happens to be centered around sexual guilt and nervousness.

Shot by Tom Harari, whose work I do not otherwise know, Love Like Poison is ecstatically visual, and its imagery is where much of the heavy lifting of the psychology, and even the story, is achieved. It is full of damnably hard lighting, giving it much higher contrast than we're used to in color cinematography; the disconcerting edge this gives the movie neatly sets off the harshness of the characters' internal lives (this is a film absolutely lousy with wickedly self-judging people; the less they hate themselves, the less the director seems interested in exploring them, as opposed to exploring their effects on the "proper" protagonist. "The harsh light of day" is a hackneyed phrase, but it got that way for a reason: you can't hide anything in direct light. This is perhaps why the moments throughout the film in which the characters seem most comfortable are also those with the least lighting (I would again point to the interactions of Anna and Jean), and why the most probing are the brightest, even when this violates the film's apparent dedication to "realism": the inside of the church during Anna's confirmation, one of the most traumatic moments she experiences in the film, is almost painfully clear and overlit, even as the church interior itself looks almost like a dungeon, with its hard corners and stone walls.

It is not, certainly, a pleasant film; nor an easy one. It yields up its meaning only reluctantly, though since the director's command of her frame leads to such memorable images, the film lingers quite long enough that the viewer has ample time to roll over that meaning. It's quite a solid achievement altogether, though I find that its chilly Frenchness seems accidental, and not a conspicuous, deliberate attempt to provoke the audience, as in the films of Bresson (a filmmaker whose style, if not his austerity, is plainly known to Quillévéré). As a debut, it is masterful, but there's a little bit too much familiarity in the themes and even the particular ways that it's discomfiting; but anything that throws this much at the audience without apology, but with such cinematic flair, deserves a hefty measure of respect, though love seems a bit too much to give, not that the film expects or asks for it.

8/10

The film - whose French title, Un poison violent, means something extremely different than its English title, though they both reference the same Serge Gainsbourg song - is the story of the coming-of-age of Anna (Clara Augarde), a teenage girl attending Catholic boarding school who has returned to her tiny village for a brief while. It is not a pleasant while: her mother, Jeanne (Lio), announces that she and Anna's father (Thierry Neuvic) are divorcing, and he has fled; though he's left his father, Jean (Michel Galabru) behind for Jeanne to take care of. Nor is this the only, or even the biggest, crisis in Anna's life: as she prepares for her confirmation - a moment of profound importance for a good Catholic girl raised by as domineering and religious a mother as Jeanne plainly is - she is aware both of an increasing sense of spiritual panic, convinced that she's just not faithful enough, and the rising tide of libido common to all young teenagers. And the tension between the two is more or less killing her.

Incident is not high on the director's list of priorities (she also wrote the screenplay, in collaboration with Mariette Désert): Love Like Poison is, to the exclusion of virtually all else, a depiction of personality. Anna's, chiefly, although there is a B-plot almost as rich in character detail involving Jeanne's growing dependence on the young new parish priest, Father François (Stefano Cassetti), whose cloudy eyes and distinctly Italian features may or may not inspire something akin to lust in the devout woman's heart, though it's far less ambiguous that he's feeling something extremely akin to lust for her. If there's a message in all of this, it's "religion creates a diseased impression of sexuality", but a polemic isn't really in the director's field of vision, either.

The film is breathtakingly subtle, presenting a number of challenging situations and allowing them to play out without comment, other than what we bring to the film as an audience. This is probably best seen in the matter of Anna and her grandfather: Jean, bedridden, corpulent, and crummy, is a high-spirited old pervert, blithely observant of his granddaughter's nubility, and yet he's also the closest she knows to a genuinely kindly soul. Part of us wants to hate and condemn him; part of us is thankful that he's there, for without him, it's difficult to say what Anna would know of familial love.

Perhaps even more unsettling than this, is the director's willing sexualisation of Anna's body - Augarde being all of 14 when the film was shot, it's almost terrifying when we see her bare breasts on camera, and when she subsequently accuses her mother (who has been spying on her naked daughter for reasons that are probably focused on her own jealousy of the girl's innocence), "Do I turn you on?" she's framed to look almost directly at the camera, a forthright challenge to the audience, or at least the part of the audience that likes naked women. In fact, the awareness of cinema's default male gaze, and the deliberate attempt to exploit and break that gaze, is a key part of the director's visual depiction of her protagonist. "Do I turn you on?" is asked, implicitly, in much of the film, and the director plainly has little respect for anyone who would respond, "yes". But I do not want to belabor this, for these issues are still less important than the exploration of character per se, which in this case happens to be centered around sexual guilt and nervousness.

Shot by Tom Harari, whose work I do not otherwise know, Love Like Poison is ecstatically visual, and its imagery is where much of the heavy lifting of the psychology, and even the story, is achieved. It is full of damnably hard lighting, giving it much higher contrast than we're used to in color cinematography; the disconcerting edge this gives the movie neatly sets off the harshness of the characters' internal lives (this is a film absolutely lousy with wickedly self-judging people; the less they hate themselves, the less the director seems interested in exploring them, as opposed to exploring their effects on the "proper" protagonist. "The harsh light of day" is a hackneyed phrase, but it got that way for a reason: you can't hide anything in direct light. This is perhaps why the moments throughout the film in which the characters seem most comfortable are also those with the least lighting (I would again point to the interactions of Anna and Jean), and why the most probing are the brightest, even when this violates the film's apparent dedication to "realism": the inside of the church during Anna's confirmation, one of the most traumatic moments she experiences in the film, is almost painfully clear and overlit, even as the church interior itself looks almost like a dungeon, with its hard corners and stone walls.

It is not, certainly, a pleasant film; nor an easy one. It yields up its meaning only reluctantly, though since the director's command of her frame leads to such memorable images, the film lingers quite long enough that the viewer has ample time to roll over that meaning. It's quite a solid achievement altogether, though I find that its chilly Frenchness seems accidental, and not a conspicuous, deliberate attempt to provoke the audience, as in the films of Bresson (a filmmaker whose style, if not his austerity, is plainly known to Quillévéré). As a debut, it is masterful, but there's a little bit too much familiarity in the themes and even the particular ways that it's discomfiting; but anything that throws this much at the audience without apology, but with such cinematic flair, deserves a hefty measure of respect, though love seems a bit too much to give, not that the film expects or asks for it.

8/10