I find the things that you do will make me feel alright

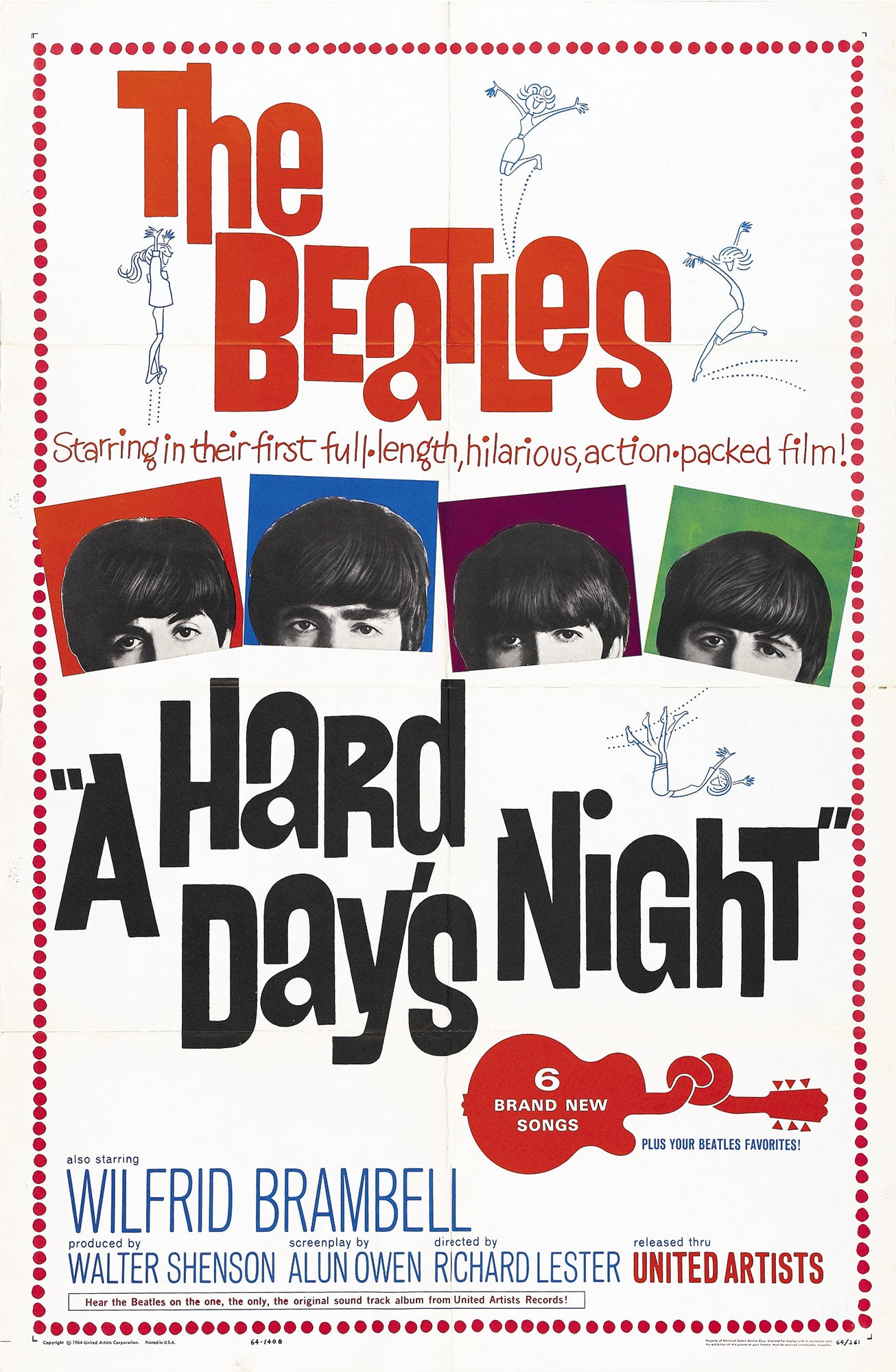

Mark Clemens made a simple request with his donation to the Carry On Campaign: that I must review either A Hard Day's Night or Help! Being something of a Beatles fan - oh yes, I am quite a trendsetter - that got me to thinking about what a good idea it would be to review EVERY film in the band's short career, and thus I hereby declare this to be Beatles Week on Antagony & Ecstasy.

In the early 1960s, in the glut of bands formed in the north of England that took inspiration from American rhythm and blues, there were four young men united under the contrived name of the Beatles. It was a tough time for anyone to break out of the background - just about everyone in those days was playing the same kind of music - and with a recent tour of the U.S. having failed to light the world on fire (the Beatles' biggest splash in this country was a three-day stint on a variety show hosted by a stiff and wholly unlikable middle-aged man), their manager hit upon the idea of trying desperately to give his boys some exposure by means of a quick cash-in movie.

Nope, can't do it. I consider myself a great master of sarcasm, but acting like The Beatles are anything but what they are - the finest, most innovative, most influential group in the history of popular music - isn't sarcasm, it's being an asshole. Though it must be said, cash-in rock 'n roll movies were a longstanding tradition stretching well back into the 1950s, and a cash-in was all that A Hard Day's Night was supposed to be. A cash-in made with some extra degree of love and care, sure - but a cash-in.

It didn't work out that way: instead, the film is a brilliant, casually revolutionary meld of avant-garde cinema, pop art, and a perfectly respectable British attitude, legitimately one of the best and most important movies of its generation. It inspired dozens of immediate copycats, not one of which is a quarter as good (not to mention its continued influence over a genre it more or less invented, the music video); it is the most sustained and successful adoption of the French Nouvelle Vague aesthetics into English-language filmmaking, and even more importantly, the best adaptation of those aesthetics into a form better-suited to English filmmaking, rather than a straightforward theft of French technique. It is perhaps the first post-modern commentary on pop culture iconography; it has one of the best original soundtracks of any cinema musical (though I don't think it's typically thought of in those terms); it's just a plain ol' masterpiece, all in all, the best British film of the 1960s, and perhaps even the best movie of 1964, one of cinema's finest anni mirabiles.

The film's quality is no accident at all: for while the four Beatles may have been young (between 21 and 23), and they may have been thrust headlong into the greatest orgasm of fame ever enjoyed by a pop act, they were intelligent and cunning, and they knew enough to demand the best. In this case, "the best" meant Alun Owen, a television writer with a keen ear for the Liverpudlian dialect spoken by the band, and Richard Lester, a director who had mightily impressed the band's intellectual frontman, John Lennon, with the 1960 short The Running, Jumping & Standing Still Film (made along with comic masterminds Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan). It was this tiny bit of abstract slapstick that marked out the direction that seemed right for the group's first feature, which was of course going to be a bit of self-indulgent marketing, but was also to be released at a key moment in their development, a period in which they were actively attempting to shift their public persona from awesomely popular boy band to serious artists making proper music. It is not a coincidence - the very opposite of a coincidence - that the album released under the name A Hard Day's Night, including all the new music from the film's soundtrack along with several other pieces, was the first Beatles album to contain nothing besides internally-composed songs (it is, in fact, the only album in their career to consist of nothing but Lennon/McCartney compositions). They longed to become the voice of intelligent, probing youth in the period of massive upheaval that was the 1960s, and A Hard Day's Night was to be an important step in that development.

The plot you know - or at least, you certainly damn well ought to. It is the height of Beatlemania (though, significantly, the word "Beatles" is never once spoken out loud), and John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Richard "Ringo Starr" Starkey (it is unquestionably the case that the musicians are playing heavily fictionalised versions of reality, enough that even the brutishly unimaginative IMDb can't find it fair to file the roles under the "As Self" category) are traveling from the north to London, to film a live show, along with managers Norm (Norman Rossington) and Shake (John Junkin), and Paul's irascible grandfather (Wilfrid Brambell). Along the way, they are hounded by ravenous female fans, forced from point to point by their managers and a shrill television director (Victor Spinetti) - as Paul's grandfather puts it, a life made up of "a train and a room and a car and a room and a room and a room". Being, after all, four young kids, the Beatles just want to goof around and have fun, and aren't really at all pleased with the regimentation of their life, so they - particularly the counterculture-icon-in-training John - do whatever they can to spend as much time as possible all to themselves in the little time they have.

There is one level upon which A Hard Day's Night is pure, unmitigated calculation, and that lies in the picture it paints of the Beatles: nominally an "all-access" sort of peek into the life of the most popular boys in music, it absolutely serves to present a deliberate, controlled version of their lives. It was this film, for a start, that forever codified the suspiciously programmatic Beatles personalities: John is the satiric wiseass, Paul is the disarming cute one, George is the placid & sensible one, Ringo is a bit of a mopey sad-sack with a big ol' heart. And it presents the altogether convenient message that the Beatles, all they really want is to make music and not have to deal with all this "fame" and "money" nonsense.

On the other hand, even that has a bit of a snarky quality, a biting of the hand that feeds them - after all, this film aimed at the hordes of Beatlemaniacs is not afraid to point out that, maybe, the Beatles' fans are a bit pushy and loud and annoying, so much so that the Beatles have to run like hell and don disguises just to get five seconds' peace. This is all said in a loving way, light and comic - but it is said.

It's that kind of not-quite-resentment for everything that marks the second level of A Hard Day's Night, which is a rebellion of sorts. Not as strident as the Rolling Stones' work of the same period, not as overt as the Who's "My Generation", but the dominant mood of the film - which, it must be said, plays rather nicely into the calculating, "let's create a dominant paradigm for our stars" nature of the thing - is one of being distinctly unsettled with the way things are, which includes the idea that just because we Beatles are famous, we have to be absolutely fulfilled and delighted. Of course it's nice to have fans and money; but other things matter. It's the constant desire to find those other things in tiny doses that drives all the conflict of this almost entirely plotless film; it's the unspoken hint of sublimated anger that hums underneath many of the genial zingers, like George's dry apology to a landowner after the band has spent the afternoon running around: "Sorry we hurt your field, mister."

It's the mixture of sullenness and comedy inherent in a line like that - or in the iconic exchange "Are you a mod or a rocker?" Um, no, I'm a mocker," or in a great many other lines and scenes - that keeps A Hard Day's Night from the self-importance that the phrase "generational angst", and especially, "1960s generational angst", usually conjures up. I'd say that it's part of the quintessential Britishness of the whole thing, except that everything from the Angry Young Men to Lindsay Anderson's if... are also quintessentially British, and are absolutely beholden to the kind of self-seriousness that the Beatles' movie mostly eschews. For, at its core, A Hard Day's Night finds the band mocking itself as well as the world around them - more to the point, mocking characters who share their name and profession, but as far as the movie per se is concerned, they're basically the same thing - for while the Beatles of the movie are definitely smarter than everyone around them, they're also aimless and silly. Silly in a generous, nonjudgmental manner; silly in a way that makes us love them, while making everyone around them look like a buffoon. But silly also in a way that makes us feel quite a bit brighter than they are. It was no doubt a source of amusement to the men who made up the Beatles to watch their public personae pricked apart this way, though perhaps also a bit too close to home (the band allegedly did not stay all the way through the film's premiere: out of boredom or embarrassment, no source says).

This is then the third level, in which A Hard Day's Night is a self-dissecting examination of pop culture as a mode of representation. It's always right at the edges of the film that the thing we call the Beatles is a fabricated construction: and Lester in particular (along with cinematographer Gilbert Taylor) finds a number of ways to explore this idea, with a grab-bag of tricks famously cribbed from the decade's French filmmakers (Jean-Luc Godard in particular). Conversations about the film always end up on "A Hard Day's Night" and "Can't Buy Me Love" as the two great musical sequences, with the latter in particular indebted to the New Wave in its use of jump-cutting, speed-ramping, and one memorable shot in which we can quite clearly see the cameraman's feet. Still, the key sequence, to me, has always been "And I Love Her", the band's sound-check song, which itself gathers a number of New Wave editing tricks (the use of dissolves in particular would have been unthinkable five years earlier), while introducing a brand new way of shooting a rock band in performance that remains, over four decades later, the best way that anybody has ever figured out how to do it. And, in what seems to me the central image of the film itself, Lester and Taylor's camera frequently pans from the band to a bank of monitors showing the band, from numerous angles.

This is a powerful image if ever I've seen one: suggesting in one breath how the pop culture mechanism fragments and splits the personality of the individuals involved (we can see two Pauls at once, but we can focus only on one of them, and which is the "correct" one?), and in the same breath reminding us that the Beatles we see are always, in effect, through a camera - so as far as the movie is concerned, the difference between "the Beatles onstage" and "the Beatles on a monitor" is nil. In both cases, they are an object to be ogled by a lens, recorded, and disseminated as product. This image is too good for Lester to use it just once; in addition to "And I Love Her", it crops up in the big show at the end of the movie, and somehow becomes more and more impressive the more times we see it.

All of this layered meaning aside, nobody would still give a damn about A Hard Day's Night except for culture theorists and media scholars if it weren't a hell of a lot of fun - one of the funniest comedies ever filmed, and one of the most breezy musicals. That the seven original songs (the ones I have not named are "I Should Have Known Better", "If I Fell", "I'm Happy Just To Dance With You", and "Tell Me Why" - incidentally, that every one of the film's original songs except the title number has a first-person title would be a rich topic for study in and of itself) are incredibly delightful, you should already know; that "Can't Buy Me Love" (the most Running, Jumping & Standing Still -esque part of the movie) is the wellspring from which all music videos have since sprung you may not know, but you can likely intuit. Obviously a major element of the film's genesis is a Beatles song delivery system, and thanks to Lester's light touch and skill with physical movement, it is a perfectly wonderful delivery system at that.

It's not as much of a given that the film would be such a great comedy - musicians aren't actors - but by tailoring the moments to the boys' limitations, Owen made certain that they'd be able to play bigger versions of themselves, finding gags without having to stretch (though George comes across as a lot handier with a one-liner than his bandmates, or maybe that's my taste. Still, there's not a single moment in any of the other performances, that can top his acerbic response when a reporter asks what he calls his hairstyle: "Arthur"). Then, by surrounding the band with gifted and ungreedy character actors the filmmakers provide a uniform base of good humor upon which the whole movie can amble along, always giving the audience a good opportunity to smile and hum along, while providing depths and depths within depths for those who want more than a spot of comedy. It's that complexity that makes A Hard Day's Night a fascinating pop culture object, and it's complexity mixed with extremely gifted technique and great writing that makes it a cinema masterpiece.

In the early 1960s, in the glut of bands formed in the north of England that took inspiration from American rhythm and blues, there were four young men united under the contrived name of the Beatles. It was a tough time for anyone to break out of the background - just about everyone in those days was playing the same kind of music - and with a recent tour of the U.S. having failed to light the world on fire (the Beatles' biggest splash in this country was a three-day stint on a variety show hosted by a stiff and wholly unlikable middle-aged man), their manager hit upon the idea of trying desperately to give his boys some exposure by means of a quick cash-in movie.

Nope, can't do it. I consider myself a great master of sarcasm, but acting like The Beatles are anything but what they are - the finest, most innovative, most influential group in the history of popular music - isn't sarcasm, it's being an asshole. Though it must be said, cash-in rock 'n roll movies were a longstanding tradition stretching well back into the 1950s, and a cash-in was all that A Hard Day's Night was supposed to be. A cash-in made with some extra degree of love and care, sure - but a cash-in.

It didn't work out that way: instead, the film is a brilliant, casually revolutionary meld of avant-garde cinema, pop art, and a perfectly respectable British attitude, legitimately one of the best and most important movies of its generation. It inspired dozens of immediate copycats, not one of which is a quarter as good (not to mention its continued influence over a genre it more or less invented, the music video); it is the most sustained and successful adoption of the French Nouvelle Vague aesthetics into English-language filmmaking, and even more importantly, the best adaptation of those aesthetics into a form better-suited to English filmmaking, rather than a straightforward theft of French technique. It is perhaps the first post-modern commentary on pop culture iconography; it has one of the best original soundtracks of any cinema musical (though I don't think it's typically thought of in those terms); it's just a plain ol' masterpiece, all in all, the best British film of the 1960s, and perhaps even the best movie of 1964, one of cinema's finest anni mirabiles.

The film's quality is no accident at all: for while the four Beatles may have been young (between 21 and 23), and they may have been thrust headlong into the greatest orgasm of fame ever enjoyed by a pop act, they were intelligent and cunning, and they knew enough to demand the best. In this case, "the best" meant Alun Owen, a television writer with a keen ear for the Liverpudlian dialect spoken by the band, and Richard Lester, a director who had mightily impressed the band's intellectual frontman, John Lennon, with the 1960 short The Running, Jumping & Standing Still Film (made along with comic masterminds Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan). It was this tiny bit of abstract slapstick that marked out the direction that seemed right for the group's first feature, which was of course going to be a bit of self-indulgent marketing, but was also to be released at a key moment in their development, a period in which they were actively attempting to shift their public persona from awesomely popular boy band to serious artists making proper music. It is not a coincidence - the very opposite of a coincidence - that the album released under the name A Hard Day's Night, including all the new music from the film's soundtrack along with several other pieces, was the first Beatles album to contain nothing besides internally-composed songs (it is, in fact, the only album in their career to consist of nothing but Lennon/McCartney compositions). They longed to become the voice of intelligent, probing youth in the period of massive upheaval that was the 1960s, and A Hard Day's Night was to be an important step in that development.

The plot you know - or at least, you certainly damn well ought to. It is the height of Beatlemania (though, significantly, the word "Beatles" is never once spoken out loud), and John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Richard "Ringo Starr" Starkey (it is unquestionably the case that the musicians are playing heavily fictionalised versions of reality, enough that even the brutishly unimaginative IMDb can't find it fair to file the roles under the "As Self" category) are traveling from the north to London, to film a live show, along with managers Norm (Norman Rossington) and Shake (John Junkin), and Paul's irascible grandfather (Wilfrid Brambell). Along the way, they are hounded by ravenous female fans, forced from point to point by their managers and a shrill television director (Victor Spinetti) - as Paul's grandfather puts it, a life made up of "a train and a room and a car and a room and a room and a room". Being, after all, four young kids, the Beatles just want to goof around and have fun, and aren't really at all pleased with the regimentation of their life, so they - particularly the counterculture-icon-in-training John - do whatever they can to spend as much time as possible all to themselves in the little time they have.

There is one level upon which A Hard Day's Night is pure, unmitigated calculation, and that lies in the picture it paints of the Beatles: nominally an "all-access" sort of peek into the life of the most popular boys in music, it absolutely serves to present a deliberate, controlled version of their lives. It was this film, for a start, that forever codified the suspiciously programmatic Beatles personalities: John is the satiric wiseass, Paul is the disarming cute one, George is the placid & sensible one, Ringo is a bit of a mopey sad-sack with a big ol' heart. And it presents the altogether convenient message that the Beatles, all they really want is to make music and not have to deal with all this "fame" and "money" nonsense.

On the other hand, even that has a bit of a snarky quality, a biting of the hand that feeds them - after all, this film aimed at the hordes of Beatlemaniacs is not afraid to point out that, maybe, the Beatles' fans are a bit pushy and loud and annoying, so much so that the Beatles have to run like hell and don disguises just to get five seconds' peace. This is all said in a loving way, light and comic - but it is said.

It's that kind of not-quite-resentment for everything that marks the second level of A Hard Day's Night, which is a rebellion of sorts. Not as strident as the Rolling Stones' work of the same period, not as overt as the Who's "My Generation", but the dominant mood of the film - which, it must be said, plays rather nicely into the calculating, "let's create a dominant paradigm for our stars" nature of the thing - is one of being distinctly unsettled with the way things are, which includes the idea that just because we Beatles are famous, we have to be absolutely fulfilled and delighted. Of course it's nice to have fans and money; but other things matter. It's the constant desire to find those other things in tiny doses that drives all the conflict of this almost entirely plotless film; it's the unspoken hint of sublimated anger that hums underneath many of the genial zingers, like George's dry apology to a landowner after the band has spent the afternoon running around: "Sorry we hurt your field, mister."

It's the mixture of sullenness and comedy inherent in a line like that - or in the iconic exchange "Are you a mod or a rocker?" Um, no, I'm a mocker," or in a great many other lines and scenes - that keeps A Hard Day's Night from the self-importance that the phrase "generational angst", and especially, "1960s generational angst", usually conjures up. I'd say that it's part of the quintessential Britishness of the whole thing, except that everything from the Angry Young Men to Lindsay Anderson's if... are also quintessentially British, and are absolutely beholden to the kind of self-seriousness that the Beatles' movie mostly eschews. For, at its core, A Hard Day's Night finds the band mocking itself as well as the world around them - more to the point, mocking characters who share their name and profession, but as far as the movie per se is concerned, they're basically the same thing - for while the Beatles of the movie are definitely smarter than everyone around them, they're also aimless and silly. Silly in a generous, nonjudgmental manner; silly in a way that makes us love them, while making everyone around them look like a buffoon. But silly also in a way that makes us feel quite a bit brighter than they are. It was no doubt a source of amusement to the men who made up the Beatles to watch their public personae pricked apart this way, though perhaps also a bit too close to home (the band allegedly did not stay all the way through the film's premiere: out of boredom or embarrassment, no source says).

This is then the third level, in which A Hard Day's Night is a self-dissecting examination of pop culture as a mode of representation. It's always right at the edges of the film that the thing we call the Beatles is a fabricated construction: and Lester in particular (along with cinematographer Gilbert Taylor) finds a number of ways to explore this idea, with a grab-bag of tricks famously cribbed from the decade's French filmmakers (Jean-Luc Godard in particular). Conversations about the film always end up on "A Hard Day's Night" and "Can't Buy Me Love" as the two great musical sequences, with the latter in particular indebted to the New Wave in its use of jump-cutting, speed-ramping, and one memorable shot in which we can quite clearly see the cameraman's feet. Still, the key sequence, to me, has always been "And I Love Her", the band's sound-check song, which itself gathers a number of New Wave editing tricks (the use of dissolves in particular would have been unthinkable five years earlier), while introducing a brand new way of shooting a rock band in performance that remains, over four decades later, the best way that anybody has ever figured out how to do it. And, in what seems to me the central image of the film itself, Lester and Taylor's camera frequently pans from the band to a bank of monitors showing the band, from numerous angles.

This is a powerful image if ever I've seen one: suggesting in one breath how the pop culture mechanism fragments and splits the personality of the individuals involved (we can see two Pauls at once, but we can focus only on one of them, and which is the "correct" one?), and in the same breath reminding us that the Beatles we see are always, in effect, through a camera - so as far as the movie is concerned, the difference between "the Beatles onstage" and "the Beatles on a monitor" is nil. In both cases, they are an object to be ogled by a lens, recorded, and disseminated as product. This image is too good for Lester to use it just once; in addition to "And I Love Her", it crops up in the big show at the end of the movie, and somehow becomes more and more impressive the more times we see it.

All of this layered meaning aside, nobody would still give a damn about A Hard Day's Night except for culture theorists and media scholars if it weren't a hell of a lot of fun - one of the funniest comedies ever filmed, and one of the most breezy musicals. That the seven original songs (the ones I have not named are "I Should Have Known Better", "If I Fell", "I'm Happy Just To Dance With You", and "Tell Me Why" - incidentally, that every one of the film's original songs except the title number has a first-person title would be a rich topic for study in and of itself) are incredibly delightful, you should already know; that "Can't Buy Me Love" (the most Running, Jumping & Standing Still -esque part of the movie) is the wellspring from which all music videos have since sprung you may not know, but you can likely intuit. Obviously a major element of the film's genesis is a Beatles song delivery system, and thanks to Lester's light touch and skill with physical movement, it is a perfectly wonderful delivery system at that.

It's not as much of a given that the film would be such a great comedy - musicians aren't actors - but by tailoring the moments to the boys' limitations, Owen made certain that they'd be able to play bigger versions of themselves, finding gags without having to stretch (though George comes across as a lot handier with a one-liner than his bandmates, or maybe that's my taste. Still, there's not a single moment in any of the other performances, that can top his acerbic response when a reporter asks what he calls his hairstyle: "Arthur"). Then, by surrounding the band with gifted and ungreedy character actors the filmmakers provide a uniform base of good humor upon which the whole movie can amble along, always giving the audience a good opportunity to smile and hum along, while providing depths and depths within depths for those who want more than a spot of comedy. It's that complexity that makes A Hard Day's Night a fascinating pop culture object, and it's complexity mixed with extremely gifted technique and great writing that makes it a cinema masterpiece.

Categories: british cinema, carry on campaign, comedies, musicals, the beatles