The films of Studio Ghibli: Take me home, to the place I belong

1994's Pom Poko was the eighth feature-length film produced by Studio Ghibli; it was the seventh to be directed by either Miyazaki Hayao or Takahata Isao. That this saturation of the studio's creative output by just two filmmakers - neither of them young men - was less than ideal needs no explanation, and thus it was that Miyazaki looked to the ranks of the studio's animators to find his successor. The man he chose was Kondo Yoshifumi, nine year's Miyazaki's junior; the two men had worked together on the first Lupin III series and Kondo had come over to Ghibli in the late 1980s.

Kondo's first project was the 1995 release Whisper of the Heart, adapted from a one-volume manga by Hiiragi Aoi. Kondo's first project; yet Miyazaki, the same man who'd taken over Kiki's Delivery Service when he concluded that nobody else could make it the way he wanted, certainly didn't prove to be a hands-off mentor. He wrote the screenplay for the film (changing it in many ways both large and small from the source material); he oversaw creation of the storyboards. But he still let Kondo take over from there, and that is what ultimately matters, for Whisper of the Heart ultimately feels like something entirely different from any given Miyazaki film: more reflective, a bit more emotionally reserved, and certainly more tuned to everyday life in the here and now.

Or to put it another way: the plot unfolds so gradually that half-way through, you'd be tempted to say that nothing really has happened, and even by the end, though you're aware that quite a lot has happened, indeed, you'd be hard pressed to say when, exactly. Of course, some of this is the responsibility of Miyazaki the writer; but Kondo surely had much to do with the film's steadfast refusal to hurry from place to place, lingering on emotional beats wherever possible and simply living with the characters for a bit before we get to see anything out of the ordinary happen to them.

In 1994, in the Tama New Town suburb of Tokyo (the same region where Pom Poko took place, in the days when it was forest and nature), there is a schoolgirl named Tsukishima Shizuku (Honna Youko). She's a voracious bookworm, and in the process of reading fantasy and studying for her pre-high school exams, she spots a pattern: several of the books she's checked out from the library were previously borrowed by an unknown male named Amasawa Seiji (there is a certain touch of melancholy that goes unremarked, but hovers over the entire movie: one of the first conversations in the film concerns the transition to all-digital library records, which will end the existence of the cards which reveal who else had checked out the books before you; and when that day comes, a story such as this one could never happen again. Nostalgia is a constant companion in Ghibli films, and it's not at its strongest here. But when you stop and think about it, it might be at its most bittersweet). Like anyone, Shizuku grows obsessed with this Amasawa Seiji, but there's plenty else to distract her in life: her sister (Yamashita Yorie) is a bit of a nag, and she has lots of preparing for graduation to get done with her friend Yuko (Kayama Maiko), and she's being annoyed by a rather smug boy (Takahasi Kazuo) who makes fun of the song she's translating for the graduation ceremony, which happens to be John Denver's "Take Me Home, Country Roads" (a recurring motif that has no right to work half as well as it does).

Most importantly, though, is when she spots a tubby cat on the train. Cats not being commuters as a rule, she is instantly fascinated, and follows it to a quiet corner of the town she'd never been to, and finds a marvelous antique shop run by a kindly old man named Nishi (Kobayashi Keiju). The boy proves to be Nishi's grandson, and he keeps annoying Shizuku, but in such a way that the kind of start to become friends, and to absolutely nobody's surprise, he turns out to be Amasawa Seiji. Between the endless supply of wonders provided by Nishi's shop, especially a stately cat doll named the Baron, and the fluttering emotions raised by Seiji's presence in her life, Shizuku turns to writing, which she quickly discovers to be an outlet like nothing else in her life; and so does she start to discover the kind of person she wants to become, though the process of becoming that person is not a perfectly smooth one.

Playing a bit like an echo of Only Yesterday, another story of how a girl turns into a woman (Honna provides the voice of that film's protagonist as a child, cementing the connection), Whisper of the Heart is perhaps the most unadulterated coming-of-age story in Ghibli's canon: we start out by learning who Shizuku is, we watch her encounter a number of different incidents that cause her to change, and we are left with a clear idea of the person she will be. It might sound slight, and it probably is, compared to the grandeur of some of Ghibli's better-known works; even Only Yesterday left me aghast at the excellence of its emotional depth, while Whisper of the Heart is satisfying on a much simpler level. It is, however, a film of truly excellent observation, depicting the details of Shizuku's world with a very necessary precision: for we start to realise that this observation is indeed the heart of the movie, and if it were any less exacting, the movie itself would be a much thinner experience, nowhere nearly so moving and honest as it proves to be.

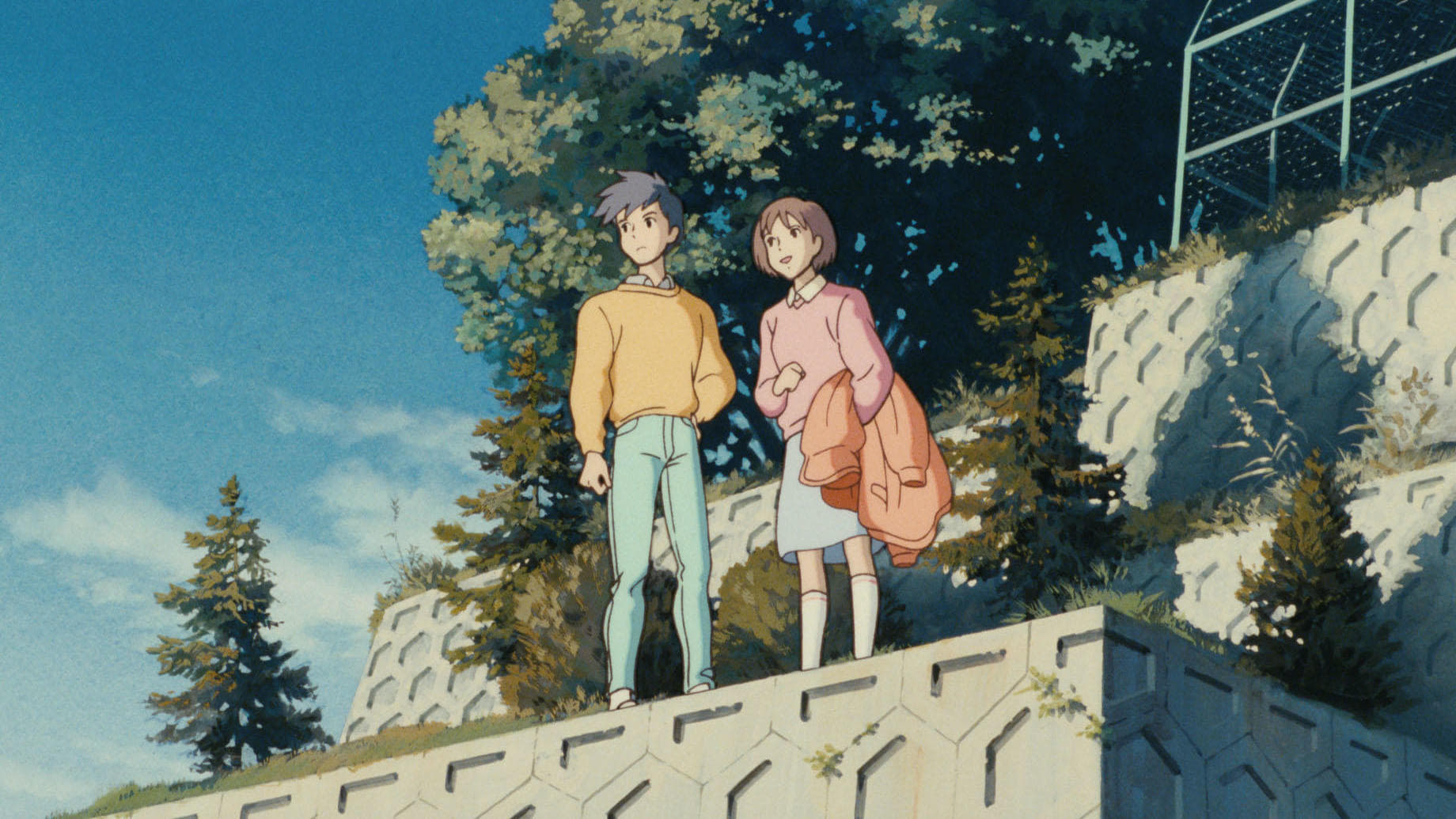

Accordingly, then, the richest pleasure of the film - even above its intimate depiction of character, I'd argue - is the totality of its sense of being, the delight with which it allows us to bask in Shizuku's world as seen through her eyes, the perspective of both a writer and a child. It is a wonderful place to find ourselves, whether it's the heavenly vision of Tama New Town as a collection of winding streets and preternaturally sun-dappled landscapes-

-or the miraculous antique store, which as Shizuku notes in both utter naïveté and wisdom, is the place where stories begin-

As a work of animation, the most important element of the film is therefore not its imaginative power, as is true of Miyazaki's greatest work, but in the control which Kondo and his team had in creating everything about their world. It is a work of great exactitude, which has been carefully designed to be as complete in itself as possible.

As a work of animation, the most important element of the film is therefore not its imaginative power, as is true of Miyazaki's greatest work, but in the control which Kondo and his team had in creating everything about their world. It is a work of great exactitude, which has been carefully designed to be as complete in itself as possible.

In fact, the only part of the film that seems to falter is the very same part that is the most out-and-out fantastic: as Shizuku writes her story, we see her inner thoughts visualised in a series of amazing vistas of impossible landscapes. These sequences, painted by Inoue Naohisa, are undeniably gorgeous, and technically important: this was one of the first uses of digital composition in Ghibli's existence, after Pom Poko used some computer-generated imagery, and the music video On Your Mark (released in theaters attached to this feature) included entire CGI landscapes.

Gloriously beautiful, without a doubt; and yet it's the one part of the film you could snip away without damaging the whole. We know from the skillful depiction of Shizuku's behavior how deeply invested she is in this world; and with the "real world" of Tama New Town already so lovely to behold, there's no striking contrast between i.e. the banality of the normal and the richness of Shizuku's thoughts. It comes across, to me at least, as nothing more than nervousness, as though the filmmakers were hedging their bets. "Well, it's animated... we better do something fantastic". Except that Ghibli's previous films had done so much to explode that fiction. Anyway, these lovely, imaginative dreamscapes end up distracting from the film as much as anything - but that does not make them the less lovely.

Gloriously beautiful, without a doubt; and yet it's the one part of the film you could snip away without damaging the whole. We know from the skillful depiction of Shizuku's behavior how deeply invested she is in this world; and with the "real world" of Tama New Town already so lovely to behold, there's no striking contrast between i.e. the banality of the normal and the richness of Shizuku's thoughts. It comes across, to me at least, as nothing more than nervousness, as though the filmmakers were hedging their bets. "Well, it's animated... we better do something fantastic". Except that Ghibli's previous films had done so much to explode that fiction. Anyway, these lovely, imaginative dreamscapes end up distracting from the film as much as anything - but that does not make them the less lovely.

(That's not to say that the film only works because of its realism, or even its magical realism: the opening seqeuence, for example, consists of haunting images of Tokyo at night underscored by Olivia Newton-John's cover of "Country Roads" - it shouldn't work at all, but it's impossible to ignore its borderline-eerie power).

I should hate to imply by stressing the scene-setting that the film comes up short on character animation, for of course it does not: though it's a bit closer to the American concept of "anime" than most of Ghibli's work to that point, with soft edges and big saucer eyes, the animators never falter a moment in presenting Shizuku's feelings written out upon her face: indeed, the range of expressions she goes through over the course of the movie is as excellent as anything of the sort in the studio's history.

Moreover, Kondo's direction is as exact and precise as his design: the framing of scenes is quite amazing at times, and the recurring visual motifs, such as the dappled light or the tendency to view characters from behind, build to subtle but effective conclusions as the film proceeds (the use of back-of-the-head shots, for example, tends to underline the degree to which these characters are trying to remain private, to hold on to their feelings - almost like we're being asked not to trespass on these difficult moments for young people who need space to work things out in their own minds).

Moreover, Kondo's direction is as exact and precise as his design: the framing of scenes is quite amazing at times, and the recurring visual motifs, such as the dappled light or the tendency to view characters from behind, build to subtle but effective conclusions as the film proceeds (the use of back-of-the-head shots, for example, tends to underline the degree to which these characters are trying to remain private, to hold on to their feelings - almost like we're being asked not to trespass on these difficult moments for young people who need space to work things out in their own minds).

If the film suffers to a certain degree from a lack of huge ambition and narrative insight (as with Miyazaki's films), or overwhelming humanism and psychological profundity (as with Takahata's), it is nevertheless absolutely true that Whisper of the Heart succeeds extremely well at doing exactly what it sets out to do: present one girl's life for a few months with honesty, to pay tribute to the joy and pain of writing, and to present with amusement and a degree of sorrow the awkwardness of first love. It's not without its flaws - I have not yet mentioned the incredibly peculiar final instant of the story, and I'd really just as soon forget that it exists - but it is a noble and pleasing work, true and touching.

Sadly, the world didn't get to find out where Kondo would go next after this fine achievement, for he died of an aneurysm in 1998, only 47 years old. He worked again as animator on Princess Mononoke, but Whisper of the Heart was his first and last project as a director. As tragic as this may be, at least this much is true: many filmmakers with much longer careers never managed to leave behind such a worthy legacy as this.

Kondo's first project was the 1995 release Whisper of the Heart, adapted from a one-volume manga by Hiiragi Aoi. Kondo's first project; yet Miyazaki, the same man who'd taken over Kiki's Delivery Service when he concluded that nobody else could make it the way he wanted, certainly didn't prove to be a hands-off mentor. He wrote the screenplay for the film (changing it in many ways both large and small from the source material); he oversaw creation of the storyboards. But he still let Kondo take over from there, and that is what ultimately matters, for Whisper of the Heart ultimately feels like something entirely different from any given Miyazaki film: more reflective, a bit more emotionally reserved, and certainly more tuned to everyday life in the here and now.

Or to put it another way: the plot unfolds so gradually that half-way through, you'd be tempted to say that nothing really has happened, and even by the end, though you're aware that quite a lot has happened, indeed, you'd be hard pressed to say when, exactly. Of course, some of this is the responsibility of Miyazaki the writer; but Kondo surely had much to do with the film's steadfast refusal to hurry from place to place, lingering on emotional beats wherever possible and simply living with the characters for a bit before we get to see anything out of the ordinary happen to them.

In 1994, in the Tama New Town suburb of Tokyo (the same region where Pom Poko took place, in the days when it was forest and nature), there is a schoolgirl named Tsukishima Shizuku (Honna Youko). She's a voracious bookworm, and in the process of reading fantasy and studying for her pre-high school exams, she spots a pattern: several of the books she's checked out from the library were previously borrowed by an unknown male named Amasawa Seiji (there is a certain touch of melancholy that goes unremarked, but hovers over the entire movie: one of the first conversations in the film concerns the transition to all-digital library records, which will end the existence of the cards which reveal who else had checked out the books before you; and when that day comes, a story such as this one could never happen again. Nostalgia is a constant companion in Ghibli films, and it's not at its strongest here. But when you stop and think about it, it might be at its most bittersweet). Like anyone, Shizuku grows obsessed with this Amasawa Seiji, but there's plenty else to distract her in life: her sister (Yamashita Yorie) is a bit of a nag, and she has lots of preparing for graduation to get done with her friend Yuko (Kayama Maiko), and she's being annoyed by a rather smug boy (Takahasi Kazuo) who makes fun of the song she's translating for the graduation ceremony, which happens to be John Denver's "Take Me Home, Country Roads" (a recurring motif that has no right to work half as well as it does).

Most importantly, though, is when she spots a tubby cat on the train. Cats not being commuters as a rule, she is instantly fascinated, and follows it to a quiet corner of the town she'd never been to, and finds a marvelous antique shop run by a kindly old man named Nishi (Kobayashi Keiju). The boy proves to be Nishi's grandson, and he keeps annoying Shizuku, but in such a way that the kind of start to become friends, and to absolutely nobody's surprise, he turns out to be Amasawa Seiji. Between the endless supply of wonders provided by Nishi's shop, especially a stately cat doll named the Baron, and the fluttering emotions raised by Seiji's presence in her life, Shizuku turns to writing, which she quickly discovers to be an outlet like nothing else in her life; and so does she start to discover the kind of person she wants to become, though the process of becoming that person is not a perfectly smooth one.

Playing a bit like an echo of Only Yesterday, another story of how a girl turns into a woman (Honna provides the voice of that film's protagonist as a child, cementing the connection), Whisper of the Heart is perhaps the most unadulterated coming-of-age story in Ghibli's canon: we start out by learning who Shizuku is, we watch her encounter a number of different incidents that cause her to change, and we are left with a clear idea of the person she will be. It might sound slight, and it probably is, compared to the grandeur of some of Ghibli's better-known works; even Only Yesterday left me aghast at the excellence of its emotional depth, while Whisper of the Heart is satisfying on a much simpler level. It is, however, a film of truly excellent observation, depicting the details of Shizuku's world with a very necessary precision: for we start to realise that this observation is indeed the heart of the movie, and if it were any less exacting, the movie itself would be a much thinner experience, nowhere nearly so moving and honest as it proves to be.

Accordingly, then, the richest pleasure of the film - even above its intimate depiction of character, I'd argue - is the totality of its sense of being, the delight with which it allows us to bask in Shizuku's world as seen through her eyes, the perspective of both a writer and a child. It is a wonderful place to find ourselves, whether it's the heavenly vision of Tama New Town as a collection of winding streets and preternaturally sun-dappled landscapes-

-or the miraculous antique store, which as Shizuku notes in both utter naïveté and wisdom, is the place where stories begin-

As a work of animation, the most important element of the film is therefore not its imaginative power, as is true of Miyazaki's greatest work, but in the control which Kondo and his team had in creating everything about their world. It is a work of great exactitude, which has been carefully designed to be as complete in itself as possible.

As a work of animation, the most important element of the film is therefore not its imaginative power, as is true of Miyazaki's greatest work, but in the control which Kondo and his team had in creating everything about their world. It is a work of great exactitude, which has been carefully designed to be as complete in itself as possible.In fact, the only part of the film that seems to falter is the very same part that is the most out-and-out fantastic: as Shizuku writes her story, we see her inner thoughts visualised in a series of amazing vistas of impossible landscapes. These sequences, painted by Inoue Naohisa, are undeniably gorgeous, and technically important: this was one of the first uses of digital composition in Ghibli's existence, after Pom Poko used some computer-generated imagery, and the music video On Your Mark (released in theaters attached to this feature) included entire CGI landscapes.

Gloriously beautiful, without a doubt; and yet it's the one part of the film you could snip away without damaging the whole. We know from the skillful depiction of Shizuku's behavior how deeply invested she is in this world; and with the "real world" of Tama New Town already so lovely to behold, there's no striking contrast between i.e. the banality of the normal and the richness of Shizuku's thoughts. It comes across, to me at least, as nothing more than nervousness, as though the filmmakers were hedging their bets. "Well, it's animated... we better do something fantastic". Except that Ghibli's previous films had done so much to explode that fiction. Anyway, these lovely, imaginative dreamscapes end up distracting from the film as much as anything - but that does not make them the less lovely.

Gloriously beautiful, without a doubt; and yet it's the one part of the film you could snip away without damaging the whole. We know from the skillful depiction of Shizuku's behavior how deeply invested she is in this world; and with the "real world" of Tama New Town already so lovely to behold, there's no striking contrast between i.e. the banality of the normal and the richness of Shizuku's thoughts. It comes across, to me at least, as nothing more than nervousness, as though the filmmakers were hedging their bets. "Well, it's animated... we better do something fantastic". Except that Ghibli's previous films had done so much to explode that fiction. Anyway, these lovely, imaginative dreamscapes end up distracting from the film as much as anything - but that does not make them the less lovely.(That's not to say that the film only works because of its realism, or even its magical realism: the opening seqeuence, for example, consists of haunting images of Tokyo at night underscored by Olivia Newton-John's cover of "Country Roads" - it shouldn't work at all, but it's impossible to ignore its borderline-eerie power).

I should hate to imply by stressing the scene-setting that the film comes up short on character animation, for of course it does not: though it's a bit closer to the American concept of "anime" than most of Ghibli's work to that point, with soft edges and big saucer eyes, the animators never falter a moment in presenting Shizuku's feelings written out upon her face: indeed, the range of expressions she goes through over the course of the movie is as excellent as anything of the sort in the studio's history.

Moreover, Kondo's direction is as exact and precise as his design: the framing of scenes is quite amazing at times, and the recurring visual motifs, such as the dappled light or the tendency to view characters from behind, build to subtle but effective conclusions as the film proceeds (the use of back-of-the-head shots, for example, tends to underline the degree to which these characters are trying to remain private, to hold on to their feelings - almost like we're being asked not to trespass on these difficult moments for young people who need space to work things out in their own minds).

Moreover, Kondo's direction is as exact and precise as his design: the framing of scenes is quite amazing at times, and the recurring visual motifs, such as the dappled light or the tendency to view characters from behind, build to subtle but effective conclusions as the film proceeds (the use of back-of-the-head shots, for example, tends to underline the degree to which these characters are trying to remain private, to hold on to their feelings - almost like we're being asked not to trespass on these difficult moments for young people who need space to work things out in their own minds).If the film suffers to a certain degree from a lack of huge ambition and narrative insight (as with Miyazaki's films), or overwhelming humanism and psychological profundity (as with Takahata's), it is nevertheless absolutely true that Whisper of the Heart succeeds extremely well at doing exactly what it sets out to do: present one girl's life for a few months with honesty, to pay tribute to the joy and pain of writing, and to present with amusement and a degree of sorrow the awkwardness of first love. It's not without its flaws - I have not yet mentioned the incredibly peculiar final instant of the story, and I'd really just as soon forget that it exists - but it is a noble and pleasing work, true and touching.

Sadly, the world didn't get to find out where Kondo would go next after this fine achievement, for he died of an aneurysm in 1998, only 47 years old. He worked again as animator on Princess Mononoke, but Whisper of the Heart was his first and last project as a director. As tragic as this may be, at least this much is true: many filmmakers with much longer careers never managed to leave behind such a worthy legacy as this.