The films of Studio Ghibli: It takes some real balls

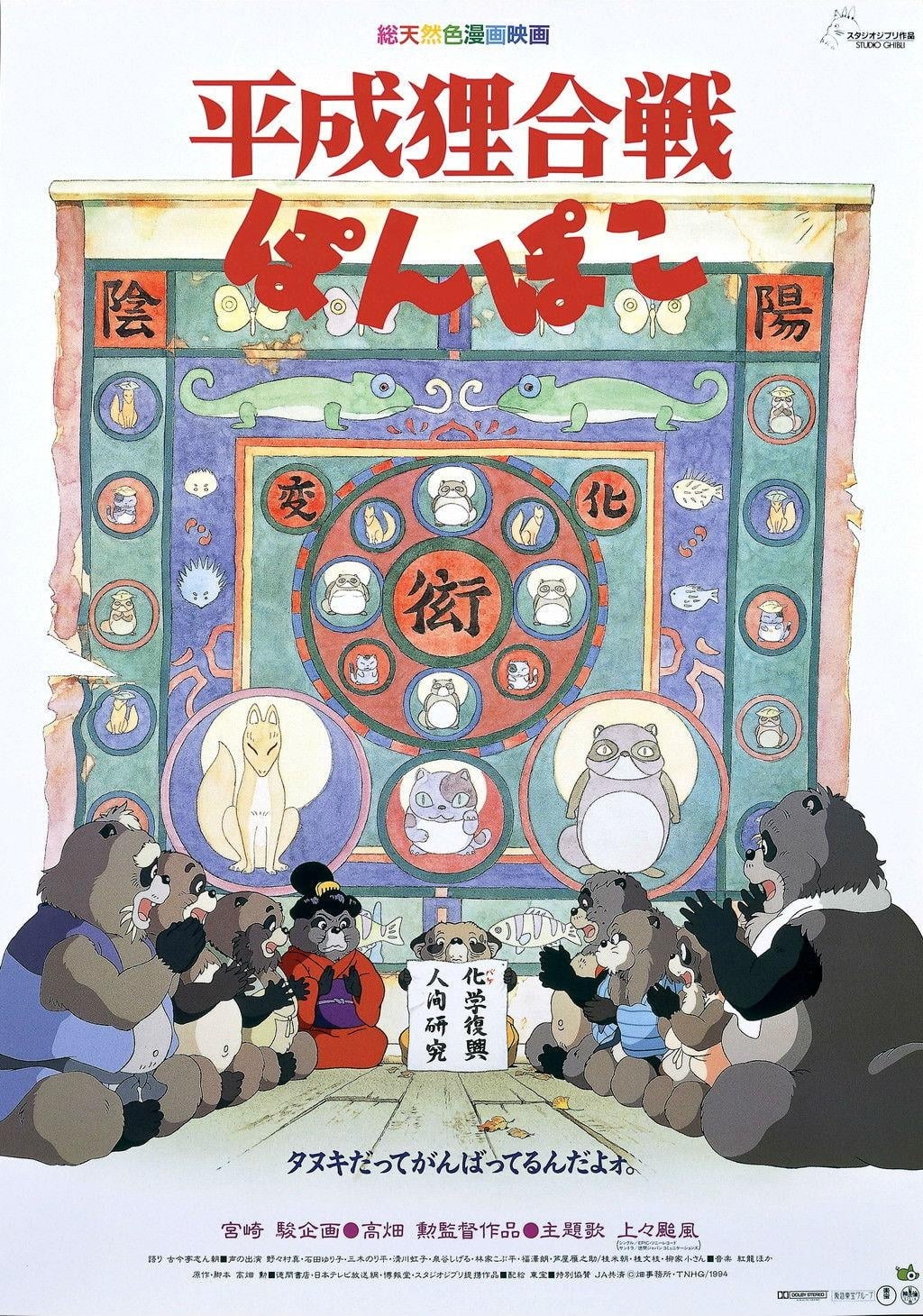

Through the end of 1993, it would be possible to make a certain generalisation about the films produced by Studio Ghibli, that would go something like this: Miyazaki Hayao directs fantasies, everybody else directs realistic stories. That neat dichotomy came screeching to a halt in 1994, when Ghibli's second-most prolific director, Takahata Isao, gave the world Pom Poko, although its non-realism takes a very distinctive form. Nor, admittedly, is the film altogether out of keeping with Takahata's previous output: another way of describing the non-Miyazaki Ghibli features is "serious stories taking place in the real world", and incredibly enough, this describes Pom Poko to a T, talking animals be damned.

The English title of the film is wildly undescriptive; a bit better is the customary alternate title The Raccoon War, though this introduces its own problems. At any rate, neither of them has a patch on the Japanese original, which Wikipedia helpfully translates as "Heisei-Era Tanuki War Ponpoko", which tells us plenty: for a start, the "X-Era" suggests a story taking place in the land of legends and myth, recalling so many of the splendidly overwrought Japanese movie titles of the '30s and '40s, stories about samurai and geisha and the like in the days before Western powers forcibly took some of the tradition out of Japanese life. And, too, the title reveals the first joke, if a joke it is: for the legendary Heisei Era happens to be our era, and it began in 1989.

As for the confusion between "raccoon" and "tanuki", that's sadly more a matter of playing to the audience's ignorance; a tanuki is a canid found on the islands of Japan, and the most sensible translation of its name (since using the Japanese word for a Japanese animal is plainly an unreasonable demand on native speakers of English) would be "raccoon dog". The people responsible for translating Heisei tanuki gassen ponpoko into English - those delightful folk at Disney - concluded that it was best to assume that children wouldn't care if the animals were simply called "raccoons", to make things easier and more familiar. This despite the fact that the tanuki prominently appears as the second-best power-up in the iconic Super Mario Bros. 3, the second-highest selling video game of its generation.

But we were talking about Pom Poko, allegedly ("pom poko", by the way, is the sound a tanuki makes when it uses its large belly as a drum). The film, which Takahata allegedly wrote when Miyazaki informed him that Ghibli needed to make a film about tanuki, concerns a population of those animals living in the Tama Hills just outside of Tokyo, whose common way of live is interrupted, violently, by the arrival in the 1960s of suburban development. By the dawn of the 1990s, the Tama tanuki have fallen into internal warfare, scrabbling over the few remaining resources; but then the wisest and oldest among them suggest that their energies would be better spent fighting the human menace, and retaking Tama for nature. So begins a years-long guerrilla war against the land developers, with the tanuki using every single trick they know.

But we were talking about Pom Poko, allegedly ("pom poko", by the way, is the sound a tanuki makes when it uses its large belly as a drum). The film, which Takahata allegedly wrote when Miyazaki informed him that Ghibli needed to make a film about tanuki, concerns a population of those animals living in the Tama Hills just outside of Tokyo, whose common way of live is interrupted, violently, by the arrival in the 1960s of suburban development. By the dawn of the 1990s, the Tama tanuki have fallen into internal warfare, scrabbling over the few remaining resources; but then the wisest and oldest among them suggest that their energies would be better spent fighting the human menace, and retaking Tama for nature. So begins a years-long guerrilla war against the land developers, with the tanuki using every single trick they know.

And they know a considerable number of tricks. Tanuki, it seems, are omnipresent in Japanese folklore, and the short version of the many things said about them is that they are held to be shape-shifting tricksters, able to take any form, and who can use their large scrotums in all sorts of applications; yet they are too good-natured and easily-distracted to use this ability to do harm. It would thus seem that the general arc of Pom Poko is that a pocket of untouched ancient Japan, threatened by the encroaching crush of Westernised culture, is forced to alter its primary characteristics (traditionally, tanuki would never attempt to war with humans) in order to remain alive in the face of modernism. This comes close to being spelled out on multiple occasions; a wise old tanuki visiting from the island of Shikoku is aghast at the fact that near Tokyo, people no longer venerate the animals or the local gods.

The tendency of "progress" to wreak havoc with tradition and nature was already old hat for Ghibli: nearly all of Miyazaki's films have a similar pro-conservation theme. But Miyazaki could never have directed Pom Poko: it is harsher and grimmer than his films tend towards. When Miyazaki depicts the grandeur and unexplored vistas of folklore, it's generally to express wonder, amazement, and delight (as in My Neighbor Totoro or Spirited Away), while as Takahata depicts the same kind of grandeur, it's to impress upon us the weight of centuries, and the gravity of the story. No film about shape-shifting canids with huge gonads can manage to be humorless, of course, and Pom Poko is all-round a much more fun movie than either Grave of the Fireflies or Only Yesterday, Takahata's earlier films with Ghibli. But there is a stark undertone to what happens that sets the film apart from Miyazaki's generally more playful approach to animation.

Ah yes, the animation. Following upon Only Yesterday, with its conflicting color palettes referring to different time periods, Takahata continued to experiment with form and representation in animation in Pom Poko, primarily but not only in the depiction of the tanuki themselves. There are three ways the animals are depicted, depending upon the context of the moment, and Takahata simply throws them at us without explanation (though it is explained early on that tanuki are bipedal when humans aren't around), and this unexplained crush of competing represenation serves to make the beginning of the film a fairly ecstatic experience of borderline-surrealism.

First, there is the realistic depiction of the tanuki in their animal form.

Then, there is the depiction - far and away the most common in the movie - of anthropomorphic tanuki; this is the predominate version of them because it is the most appealing and relatable, a cartoon spiked with realistic movement and shape, the version of the tanuki we humans are likeliest to respond to.

Then, there is the depiction - far and away the most common in the movie - of anthropomorphic tanuki; this is the predominate version of them because it is the most appealing and relatable, a cartoon spiked with realistic movement and shape, the version of the tanuki we humans are likeliest to respond to.

Finally, there is the soft, supremely cartoonish version of the animals whenever they are in a state of absent-mindedness or befuddlement; caused either by their reveries of eating, or by moments of bliss, or by getting a good thwack. This design was specifically inspired by the work of manga artist Sugiura Shigeru, whose work Takahata admired.

Finally, there is the soft, supremely cartoonish version of the animals whenever they are in a state of absent-mindedness or befuddlement; caused either by their reveries of eating, or by moments of bliss, or by getting a good thwack. This design was specifically inspired by the work of manga artist Sugiura Shigeru, whose work Takahata admired.

In the hands of a lesser filmmaker this mish-mash of styles could be terribly confused and wandering, but Takahata uses it to guide our emotions through what turns out to be a rigorous, demanding narrative, deeply rooted in folkloric traditions that most Westerners probably know little about - certainly, I had to do no small amount of research to make heads or tails of the movie. Pom Poko does not stop to explain itself, and in this it's not unlike Miyazaki's later Shinto-heavy films Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away; but the sheer wealth of allusion in Takahata's film makes it that much more daunting, although it's intensely rewarding if you do the homework - or, presumably, if you were raised with Japanese folkloric traditions.

In the hands of a lesser filmmaker this mish-mash of styles could be terribly confused and wandering, but Takahata uses it to guide our emotions through what turns out to be a rigorous, demanding narrative, deeply rooted in folkloric traditions that most Westerners probably know little about - certainly, I had to do no small amount of research to make heads or tails of the movie. Pom Poko does not stop to explain itself, and in this it's not unlike Miyazaki's later Shinto-heavy films Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away; but the sheer wealth of allusion in Takahata's film makes it that much more daunting, although it's intensely rewarding if you do the homework - or, presumably, if you were raised with Japanese folkloric traditions.

Again, this it most heavily the case in the opening sequence of the film, where Takahata seems almost gleefully eager to make sure that we can't keep up. It's exhilarating to make the attempt, though, for some of the best parts of Pom Poko are those in which the real world and folklore collide in messy, dizzying ways. There's an extended scene in the second half that exemplifies this: the tanuki have all combined their energies to create a goblin parade in the streets of the city pressing hard upon their forest, and for several minutes the plot essentially shuts down to present the spectacle of traditional monsters walking the streets of a blandly contemporary city.

It's the moment that best encapsulates what seems to me the central message of Pom Poko: the conflict between the values of the past and the present, and the resultant destruction of things that matter in the name of human expansion. But it is certainly not the only moment, and it's arguably not the most memorable, visually, if only because some of the other shots are so intensely unusual. This shot from early in the film, of a leaf being devoured by tiny aphid-like earth movers, isn't even the most surreal image in the sequence it comes from, but it gets at what I'm talking about: Takahata's visual dramatisation of his pro-environment, pro-tradition themes with bold, unexpected imagery.

It's the moment that best encapsulates what seems to me the central message of Pom Poko: the conflict between the values of the past and the present, and the resultant destruction of things that matter in the name of human expansion. But it is certainly not the only moment, and it's arguably not the most memorable, visually, if only because some of the other shots are so intensely unusual. This shot from early in the film, of a leaf being devoured by tiny aphid-like earth movers, isn't even the most surreal image in the sequence it comes from, but it gets at what I'm talking about: Takahata's visual dramatisation of his pro-environment, pro-tradition themes with bold, unexpected imagery.

In the end, if Pom Poko is a tremendously moving film - and it is, though perhaps not as moving as Takahata's earlier Ghibli features (what could be as moving as Grave of the Fireflies, after all?) - it's not ultimately because of the intelligence of the message, but its sincerity, and the characters used to present the story. Humanism was then, as ever, the watchword of the studio, and this depiction of rampant progress destroying beautiful things wouldn't mean half as much if we weren't made to feel the love the tanuki have for their land and each other; but I'll leave the specifics as a discovery for the viewer. Save to say that, even if the heroes are magic raccoon dogs, they are still wonderfully-etched people, whose tribulations form the backbone of an excellent contribution to Ghibli's legacy of pro-environment fables about the magic of the natural world and the emptiness of crowded cities. Pom Poko is not quite a masterpiece, but it's grand and rich and epic, a heady movie whose talking animal trappings do not even begin to suggest its potency.

In the end, if Pom Poko is a tremendously moving film - and it is, though perhaps not as moving as Takahata's earlier Ghibli features (what could be as moving as Grave of the Fireflies, after all?) - it's not ultimately because of the intelligence of the message, but its sincerity, and the characters used to present the story. Humanism was then, as ever, the watchword of the studio, and this depiction of rampant progress destroying beautiful things wouldn't mean half as much if we weren't made to feel the love the tanuki have for their land and each other; but I'll leave the specifics as a discovery for the viewer. Save to say that, even if the heroes are magic raccoon dogs, they are still wonderfully-etched people, whose tribulations form the backbone of an excellent contribution to Ghibli's legacy of pro-environment fables about the magic of the natural world and the emptiness of crowded cities. Pom Poko is not quite a masterpiece, but it's grand and rich and epic, a heady movie whose talking animal trappings do not even begin to suggest its potency.

The English title of the film is wildly undescriptive; a bit better is the customary alternate title The Raccoon War, though this introduces its own problems. At any rate, neither of them has a patch on the Japanese original, which Wikipedia helpfully translates as "Heisei-Era Tanuki War Ponpoko", which tells us plenty: for a start, the "X-Era" suggests a story taking place in the land of legends and myth, recalling so many of the splendidly overwrought Japanese movie titles of the '30s and '40s, stories about samurai and geisha and the like in the days before Western powers forcibly took some of the tradition out of Japanese life. And, too, the title reveals the first joke, if a joke it is: for the legendary Heisei Era happens to be our era, and it began in 1989.

As for the confusion between "raccoon" and "tanuki", that's sadly more a matter of playing to the audience's ignorance; a tanuki is a canid found on the islands of Japan, and the most sensible translation of its name (since using the Japanese word for a Japanese animal is plainly an unreasonable demand on native speakers of English) would be "raccoon dog". The people responsible for translating Heisei tanuki gassen ponpoko into English - those delightful folk at Disney - concluded that it was best to assume that children wouldn't care if the animals were simply called "raccoons", to make things easier and more familiar. This despite the fact that the tanuki prominently appears as the second-best power-up in the iconic Super Mario Bros. 3, the second-highest selling video game of its generation.

But we were talking about Pom Poko, allegedly ("pom poko", by the way, is the sound a tanuki makes when it uses its large belly as a drum). The film, which Takahata allegedly wrote when Miyazaki informed him that Ghibli needed to make a film about tanuki, concerns a population of those animals living in the Tama Hills just outside of Tokyo, whose common way of live is interrupted, violently, by the arrival in the 1960s of suburban development. By the dawn of the 1990s, the Tama tanuki have fallen into internal warfare, scrabbling over the few remaining resources; but then the wisest and oldest among them suggest that their energies would be better spent fighting the human menace, and retaking Tama for nature. So begins a years-long guerrilla war against the land developers, with the tanuki using every single trick they know.

But we were talking about Pom Poko, allegedly ("pom poko", by the way, is the sound a tanuki makes when it uses its large belly as a drum). The film, which Takahata allegedly wrote when Miyazaki informed him that Ghibli needed to make a film about tanuki, concerns a population of those animals living in the Tama Hills just outside of Tokyo, whose common way of live is interrupted, violently, by the arrival in the 1960s of suburban development. By the dawn of the 1990s, the Tama tanuki have fallen into internal warfare, scrabbling over the few remaining resources; but then the wisest and oldest among them suggest that their energies would be better spent fighting the human menace, and retaking Tama for nature. So begins a years-long guerrilla war against the land developers, with the tanuki using every single trick they know.And they know a considerable number of tricks. Tanuki, it seems, are omnipresent in Japanese folklore, and the short version of the many things said about them is that they are held to be shape-shifting tricksters, able to take any form, and who can use their large scrotums in all sorts of applications; yet they are too good-natured and easily-distracted to use this ability to do harm. It would thus seem that the general arc of Pom Poko is that a pocket of untouched ancient Japan, threatened by the encroaching crush of Westernised culture, is forced to alter its primary characteristics (traditionally, tanuki would never attempt to war with humans) in order to remain alive in the face of modernism. This comes close to being spelled out on multiple occasions; a wise old tanuki visiting from the island of Shikoku is aghast at the fact that near Tokyo, people no longer venerate the animals or the local gods.

The tendency of "progress" to wreak havoc with tradition and nature was already old hat for Ghibli: nearly all of Miyazaki's films have a similar pro-conservation theme. But Miyazaki could never have directed Pom Poko: it is harsher and grimmer than his films tend towards. When Miyazaki depicts the grandeur and unexplored vistas of folklore, it's generally to express wonder, amazement, and delight (as in My Neighbor Totoro or Spirited Away), while as Takahata depicts the same kind of grandeur, it's to impress upon us the weight of centuries, and the gravity of the story. No film about shape-shifting canids with huge gonads can manage to be humorless, of course, and Pom Poko is all-round a much more fun movie than either Grave of the Fireflies or Only Yesterday, Takahata's earlier films with Ghibli. But there is a stark undertone to what happens that sets the film apart from Miyazaki's generally more playful approach to animation.

Ah yes, the animation. Following upon Only Yesterday, with its conflicting color palettes referring to different time periods, Takahata continued to experiment with form and representation in animation in Pom Poko, primarily but not only in the depiction of the tanuki themselves. There are three ways the animals are depicted, depending upon the context of the moment, and Takahata simply throws them at us without explanation (though it is explained early on that tanuki are bipedal when humans aren't around), and this unexplained crush of competing represenation serves to make the beginning of the film a fairly ecstatic experience of borderline-surrealism.

First, there is the realistic depiction of the tanuki in their animal form.

Then, there is the depiction - far and away the most common in the movie - of anthropomorphic tanuki; this is the predominate version of them because it is the most appealing and relatable, a cartoon spiked with realistic movement and shape, the version of the tanuki we humans are likeliest to respond to.

Then, there is the depiction - far and away the most common in the movie - of anthropomorphic tanuki; this is the predominate version of them because it is the most appealing and relatable, a cartoon spiked with realistic movement and shape, the version of the tanuki we humans are likeliest to respond to. Finally, there is the soft, supremely cartoonish version of the animals whenever they are in a state of absent-mindedness or befuddlement; caused either by their reveries of eating, or by moments of bliss, or by getting a good thwack. This design was specifically inspired by the work of manga artist Sugiura Shigeru, whose work Takahata admired.

Finally, there is the soft, supremely cartoonish version of the animals whenever they are in a state of absent-mindedness or befuddlement; caused either by their reveries of eating, or by moments of bliss, or by getting a good thwack. This design was specifically inspired by the work of manga artist Sugiura Shigeru, whose work Takahata admired. In the hands of a lesser filmmaker this mish-mash of styles could be terribly confused and wandering, but Takahata uses it to guide our emotions through what turns out to be a rigorous, demanding narrative, deeply rooted in folkloric traditions that most Westerners probably know little about - certainly, I had to do no small amount of research to make heads or tails of the movie. Pom Poko does not stop to explain itself, and in this it's not unlike Miyazaki's later Shinto-heavy films Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away; but the sheer wealth of allusion in Takahata's film makes it that much more daunting, although it's intensely rewarding if you do the homework - or, presumably, if you were raised with Japanese folkloric traditions.

In the hands of a lesser filmmaker this mish-mash of styles could be terribly confused and wandering, but Takahata uses it to guide our emotions through what turns out to be a rigorous, demanding narrative, deeply rooted in folkloric traditions that most Westerners probably know little about - certainly, I had to do no small amount of research to make heads or tails of the movie. Pom Poko does not stop to explain itself, and in this it's not unlike Miyazaki's later Shinto-heavy films Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away; but the sheer wealth of allusion in Takahata's film makes it that much more daunting, although it's intensely rewarding if you do the homework - or, presumably, if you were raised with Japanese folkloric traditions.Again, this it most heavily the case in the opening sequence of the film, where Takahata seems almost gleefully eager to make sure that we can't keep up. It's exhilarating to make the attempt, though, for some of the best parts of Pom Poko are those in which the real world and folklore collide in messy, dizzying ways. There's an extended scene in the second half that exemplifies this: the tanuki have all combined their energies to create a goblin parade in the streets of the city pressing hard upon their forest, and for several minutes the plot essentially shuts down to present the spectacle of traditional monsters walking the streets of a blandly contemporary city.

It's the moment that best encapsulates what seems to me the central message of Pom Poko: the conflict between the values of the past and the present, and the resultant destruction of things that matter in the name of human expansion. But it is certainly not the only moment, and it's arguably not the most memorable, visually, if only because some of the other shots are so intensely unusual. This shot from early in the film, of a leaf being devoured by tiny aphid-like earth movers, isn't even the most surreal image in the sequence it comes from, but it gets at what I'm talking about: Takahata's visual dramatisation of his pro-environment, pro-tradition themes with bold, unexpected imagery.

It's the moment that best encapsulates what seems to me the central message of Pom Poko: the conflict between the values of the past and the present, and the resultant destruction of things that matter in the name of human expansion. But it is certainly not the only moment, and it's arguably not the most memorable, visually, if only because some of the other shots are so intensely unusual. This shot from early in the film, of a leaf being devoured by tiny aphid-like earth movers, isn't even the most surreal image in the sequence it comes from, but it gets at what I'm talking about: Takahata's visual dramatisation of his pro-environment, pro-tradition themes with bold, unexpected imagery. In the end, if Pom Poko is a tremendously moving film - and it is, though perhaps not as moving as Takahata's earlier Ghibli features (what could be as moving as Grave of the Fireflies, after all?) - it's not ultimately because of the intelligence of the message, but its sincerity, and the characters used to present the story. Humanism was then, as ever, the watchword of the studio, and this depiction of rampant progress destroying beautiful things wouldn't mean half as much if we weren't made to feel the love the tanuki have for their land and each other; but I'll leave the specifics as a discovery for the viewer. Save to say that, even if the heroes are magic raccoon dogs, they are still wonderfully-etched people, whose tribulations form the backbone of an excellent contribution to Ghibli's legacy of pro-environment fables about the magic of the natural world and the emptiness of crowded cities. Pom Poko is not quite a masterpiece, but it's grand and rich and epic, a heady movie whose talking animal trappings do not even begin to suggest its potency.

In the end, if Pom Poko is a tremendously moving film - and it is, though perhaps not as moving as Takahata's earlier Ghibli features (what could be as moving as Grave of the Fireflies, after all?) - it's not ultimately because of the intelligence of the message, but its sincerity, and the characters used to present the story. Humanism was then, as ever, the watchword of the studio, and this depiction of rampant progress destroying beautiful things wouldn't mean half as much if we weren't made to feel the love the tanuki have for their land and each other; but I'll leave the specifics as a discovery for the viewer. Save to say that, even if the heroes are magic raccoon dogs, they are still wonderfully-etched people, whose tribulations form the backbone of an excellent contribution to Ghibli's legacy of pro-environment fables about the magic of the natural world and the emptiness of crowded cities. Pom Poko is not quite a masterpiece, but it's grand and rich and epic, a heady movie whose talking animal trappings do not even begin to suggest its potency.